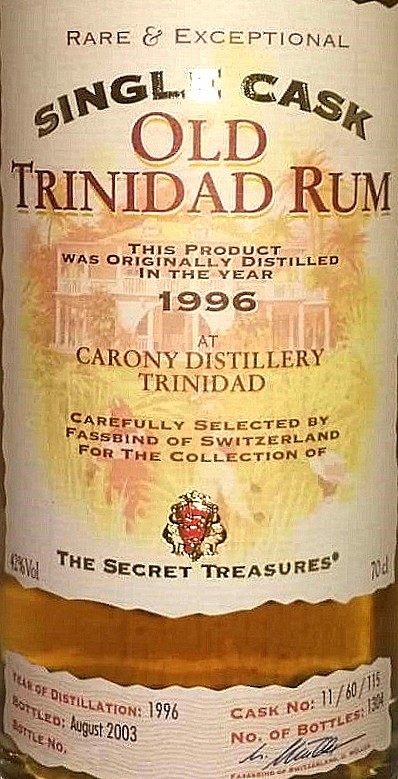

There are some older bottles in the review queue for products from what I term the “classic” era of the Swiss / German outfit of Secret Treasures, and it’s perhaps time to push them out the door in case some curious person ever wants to research them for an auction listing or something. Because what Secret Treasures are making now is completely different from what they did then, as I remarked in my brief company notes for last week’s entry on the “Carony” rum they released in 2003.

There are some older bottles in the review queue for products from what I term the “classic” era of the Swiss / German outfit of Secret Treasures, and it’s perhaps time to push them out the door in case some curious person ever wants to research them for an auction listing or something. Because what Secret Treasures are making now is completely different from what they did then, as I remarked in my brief company notes for last week’s entry on the “Carony” rum they released in 2003.

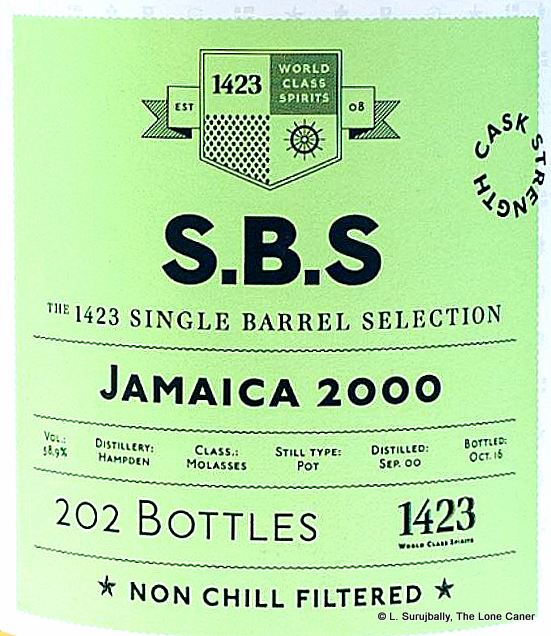

In short, from a traditional indie bottler who exactingly and carefully selects single barrels from a broker and bottles those, the company has of late gone more in the direction of a branded distributor, like, say, 1423 and its Companero line. That’s not a criticism, just an observation: after all, there’s a ton of little single-barrel-releasing indies out there already – one more won’t be missed – and not many go with the less glamorous route of releasing blends in quantity, though those tend to be low-rent reliable money spinners.

But returning to Secret Treasures’ rums of “the good old days”. This one is from Venezuela: column still product, 42% ABV, 1716 bottle outturn. The label is in that old-fashioned design, noting the date of distillation as 1992 and the distillery of origin as Pampero — but it should be noted there is a “new-style label” pot-still edition released in 2002 with a completely different layout, sharing some of the same stats, the reason for which is unknown. As an aside for the curious, the Venezuelan Pampero distillery itself was formed in 1938 and remained a family concern until it was sold to Guiness in 1991; it is now a Diageo subsidiary, making the Pampero series of light rums like the Especial, Anejo, Seleccion and Oro. Clearly they also did bulk rum sales back in the 1990s.

So that’s the schtick. The rum tasting now. Sorry for the instant spoiler, but it’s meh. The nose is okay and provided one has not already had something stronger (I had not) then aromas of caramel, creme brulee and toffee can easily be discerned, with some light oakiness, dark chocolate, smoke and old leather. A touch of indeterminate fruitiness sets these off, some unsweetened yoghurt, plus vague citrus — and that word is a giveaway, because this whole thing is like that: vague.

Tasting it reinforces the impression of sleepy absent-mindedness. The rum tastes warm, quite easy, creamy, with both salt and sweet elements, like a good sweet soya sauce. Caramel and toffee again, a hot strong latte, oak, molasses and a nice touch of mint. The citrus wandered off somewhere and the fruits are all asleep. This is not a palate guaranteed to impress, I’m afraid. The finish is odd: it’s surprisingly long lasting; nice and warm, some molasses, coffee, bon bons, but it begs the question of where all the aromas and final closing tastes have vanished to.

You’re tasting some alcoholic rummy stuff, sure, but what is it? That’s the review in a nutshell, and I doubt my score would have been substantially higher even back in the day when I was pleased with less. You sense there’s more in there, but it never quite wakes up and represents. From where I’m standing, it’s thin tea — a light and relatively simple, a quiet rum that rocks no boats, makes no noise, takes no prisoners. While undeniably falling into the “rum” category, what it really represents is a failure to engage the drinker, then or now – which may be the reason nobody remembers it in 2021, or even cares that they don’t.

(#820)(78/100)

Other notes

- Comes from a blend of four barrels

- Sold on Whisky Auction for £50 in 2018. Rumauctioneer’s May 2021 session has a “new design” blue label bottle noted above, currently bid to £17

Historical background

Initially Secret Treasures was the brand of a Swiss concern called Fassbind SA (SA stands for Société Anonyme, the equivalent to PLC – the wesbite is at www.Fassbind.ch) — who had been in the spirits business since 1846 when when Gottfried I. Fassbind founded the “Alte Urschwyzer” distillery in Oberarth to make eau de vie (a schnapps). He was a descendant of Dutch coopers who had emigrated to Switzerland in the 13th century and thus laid the foundation for what remains Switzerland’s oldest distillery.

They make grappa, schnapps and other spirits and branched out into rums in the early 2000s but not as a producer: in the usual fashion, rums at that time were sourced, aged at the origin distillery (it is unclear whether this is still happening in 2021), and then shipped to Switzerland for dilution with Swiss spring water to drinking strength (no other inclusions). In that way they conformed to the principles of many of the modern indies.

Fassbind’s local distribution was acquired in 2014 by Best Taste Trading GMBH, a Swiss distributor, yet they seem to have walked away from the rum side of the business, as the company website makes mention of the rum line at all. Current labels on newer editions of the Secret Treasures line refers to a German liquor distribution company called Haromex as the bottler, which some further digging shows as acquiring the Secret Treasures brand name back in 2005: perhaps Fassbind or Best Taste Trading had no interest in the indie bottling operation and sold it off as neither Swiss concern has any of the branded bottles in their portfolio.

Certainly the business has changed: there are no more of the pale yellow labels and sourced single barrel expressions as I found back in 2012. Now Secret Treasures is all standard strength anonymous blends like aged “Caribbean” and “South American” rum, a completely new bottle design and the Haromex logo prominently displayed with the words “Product of Germany” on the label.

In the maelstrom of ongoing indie releases coming at us from every direction almost every month, it’s easy to overlook some of the older rums, or even some of the older companies. Secret Treasures is one of these — I had discovered their charms on the same trip where I found the first Veliers, all those long years ago, at a time when the concept of independent bottlers was a relatively small scale phenomenon. Back then I bought the company’s

In the maelstrom of ongoing indie releases coming at us from every direction almost every month, it’s easy to overlook some of the older rums, or even some of the older companies. Secret Treasures is one of these — I had discovered their charms on the same trip where I found the first Veliers, all those long years ago, at a time when the concept of independent bottlers was a relatively small scale phenomenon. Back then I bought the company’s  A salty sweet sugar water greets the tongue with warmth and firmness. All the fleshy and watery fruits we’re familiar with parade around – pears, watermelons, white guavas, papaya, kiwi fruits, even cucumbers all take a bow. A trace of olives and occasional whiff of strawberries and petrol are barely noticeable, so one can only wonder where, after such a promising beginning, they all vanished to. Eloped, maybe. Certainly they bailed and left the rum with nothing but memories and a good wish to lead to its inevitably disappointing denouement, which was short, breathy, light and watery, and barely registered some vanilla, brine, a fruit or two and exactly zero points of distinction.

A salty sweet sugar water greets the tongue with warmth and firmness. All the fleshy and watery fruits we’re familiar with parade around – pears, watermelons, white guavas, papaya, kiwi fruits, even cucumbers all take a bow. A trace of olives and occasional whiff of strawberries and petrol are barely noticeable, so one can only wonder where, after such a promising beginning, they all vanished to. Eloped, maybe. Certainly they bailed and left the rum with nothing but memories and a good wish to lead to its inevitably disappointing denouement, which was short, breathy, light and watery, and barely registered some vanilla, brine, a fruit or two and exactly zero points of distinction.

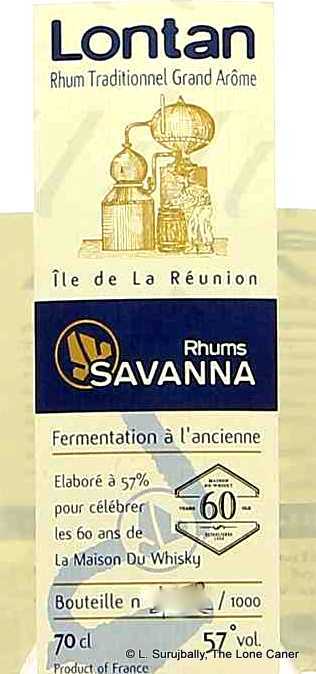

Still, this 57% ABV grand arôme, which was released in 2016 for La Maison Du Whisky’s 60th Anniversary (they went into partnership with Velier the following year and formed LM&V), seemed at pains to make the point yet again. In this case, it clearly wanted to channel a cachaca duking it out with a DOK, for it nosed pretty much like they were having a serious disagreement: vegetables and oversweet fruits decomposing on a hot day in a market someplace tropical; herbs, wet grass, sweet pickles, hot dog relish (I know what this sounds like!); sugar water; iodine, papaya, strawberries; wax, brine and cucumbers in a light pimento-soaked vinegar. I mean, seriously, does that remind you of any rum you’ve ever tried? I both liked it and wondered where the rum was hiding.

Still, this 57% ABV grand arôme, which was released in 2016 for La Maison Du Whisky’s 60th Anniversary (they went into partnership with Velier the following year and formed LM&V), seemed at pains to make the point yet again. In this case, it clearly wanted to channel a cachaca duking it out with a DOK, for it nosed pretty much like they were having a serious disagreement: vegetables and oversweet fruits decomposing on a hot day in a market someplace tropical; herbs, wet grass, sweet pickles, hot dog relish (I know what this sounds like!); sugar water; iodine, papaya, strawberries; wax, brine and cucumbers in a light pimento-soaked vinegar. I mean, seriously, does that remind you of any rum you’ve ever tried? I both liked it and wondered where the rum was hiding. This is not the first Demerara rum that the venerable Italian indie bottler Moon Import has aged in sherry barrels: the superb

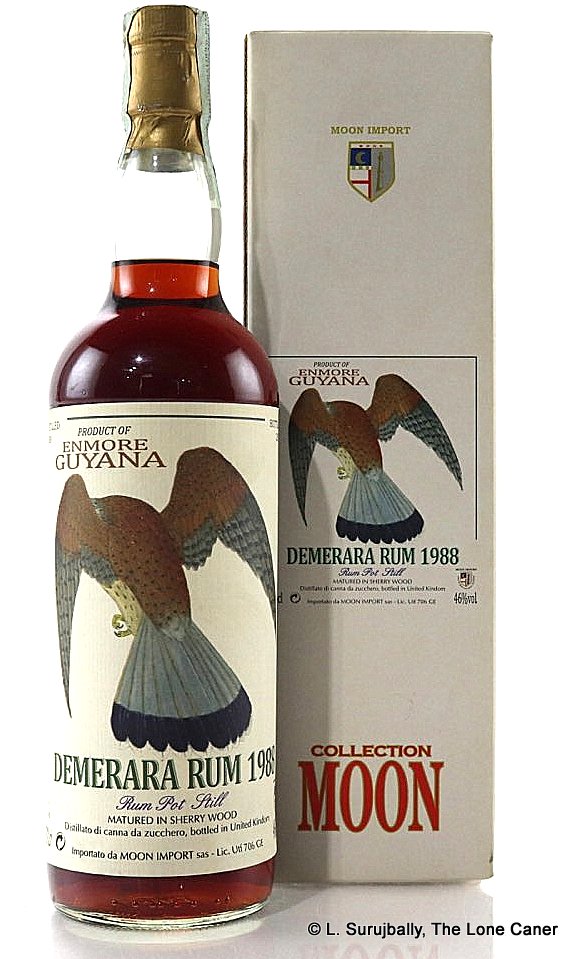

This is not the first Demerara rum that the venerable Italian indie bottler Moon Import has aged in sherry barrels: the superb

Opinion

Opinion

Whatever the case, I must advise you that if you like agricoles at all, those smaller names and lesser known establishments like Dillon should be on your radar. Not all of the rhums they make are double-digit aged, so those that are, even if farmed out to a third party, are even more worth looking at. Just smell this one, for example: it’s a fruitarian’s wet dream. In fact, the aroma almost strikes me like a very good Riesling mixing it up with a 7-up, if you could conceive of such an unlikely pairing. Lighter than the

Whatever the case, I must advise you that if you like agricoles at all, those smaller names and lesser known establishments like Dillon should be on your radar. Not all of the rhums they make are double-digit aged, so those that are, even if farmed out to a third party, are even more worth looking at. Just smell this one, for example: it’s a fruitarian’s wet dream. In fact, the aroma almost strikes me like a very good Riesling mixing it up with a 7-up, if you could conceive of such an unlikely pairing. Lighter than the

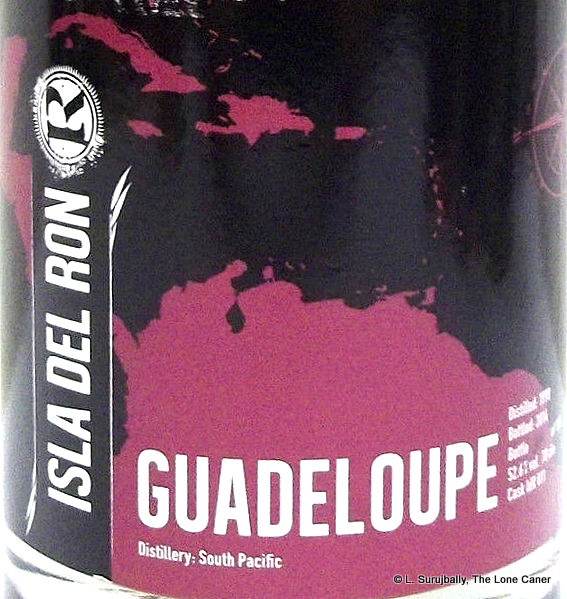

The nose doesn’t help narrow down the origin (though I have my suspicions), and the palate doesn’t either – but it

The nose doesn’t help narrow down the origin (though I have my suspicions), and the palate doesn’t either – but it

I do, on the other hand, like the taste. It’s warm and rich and the Enmore still profile – freshly sawn lumber, sawdust, pencil shavings – is clear. Also sour cream, eggnog, and bags of dried, dark fruits (raisins, prunes, dried plums) mix it up with a nice touch of sandalwood. It takes its own sweet time getting the the point and is a little discombobulated throughout, but I can’t argue with the stewed apples, dried orange peel, ripe red guavas and licorice – it’s nice. The finish is quite solid, if unexceptional: it lasts a fair bit, and you’re left with closing notes of licorice, oak chips, vanilla, dried fruit and black cake.

I do, on the other hand, like the taste. It’s warm and rich and the Enmore still profile – freshly sawn lumber, sawdust, pencil shavings – is clear. Also sour cream, eggnog, and bags of dried, dark fruits (raisins, prunes, dried plums) mix it up with a nice touch of sandalwood. It takes its own sweet time getting the the point and is a little discombobulated throughout, but I can’t argue with the stewed apples, dried orange peel, ripe red guavas and licorice – it’s nice. The finish is quite solid, if unexceptional: it lasts a fair bit, and you’re left with closing notes of licorice, oak chips, vanilla, dried fruit and black cake.

Depaz’s 45% rhum blanc agricole is not one of these uber-exclusive, limited-edition craft whites that uber-dorks are frothing over. But the quality and taste of even this standard white shows exactly how good the

Depaz’s 45% rhum blanc agricole is not one of these uber-exclusive, limited-edition craft whites that uber-dorks are frothing over. But the quality and taste of even this standard white shows exactly how good the

Tasting notes. The nose is nice. At under 50% not too much sharpness, just a good solid heat, redolent of soda, fanta, coca cola and strawberries. There’s a trace of coffee and rye bread, and also a nice fruity background of apples, green grapes, yellow mangoes and kiwi fruit. It develops well and no fault can found with the balance among these disparate elements.

Tasting notes. The nose is nice. At under 50% not too much sharpness, just a good solid heat, redolent of soda, fanta, coca cola and strawberries. There’s a trace of coffee and rye bread, and also a nice fruity background of apples, green grapes, yellow mangoes and kiwi fruit. It develops well and no fault can found with the balance among these disparate elements.

Does this multiple wood ageing result in anything worth drinking? Yes it does – the extra year seems to have had an interesting and salutary effect on the profile – though at 42.7% it remains as easy and soft as its siblings. The nose, for example, is a nice step up: cardboard, musty paper, some dunder of spoiled bananas skins, plus strawberries and soft pineapple or two and brine (which, I swear, made me think of Hawaiian pizza). Caramel and bitter dark chocolate round things off. It’s a relatively easy sniff, inoffensive yet solid.

Does this multiple wood ageing result in anything worth drinking? Yes it does – the extra year seems to have had an interesting and salutary effect on the profile – though at 42.7% it remains as easy and soft as its siblings. The nose, for example, is a nice step up: cardboard, musty paper, some dunder of spoiled bananas skins, plus strawberries and soft pineapple or two and brine (which, I swear, made me think of Hawaiian pizza). Caramel and bitter dark chocolate round things off. It’s a relatively easy sniff, inoffensive yet solid.

La Rhumerie de Chamarel, that Mauritius outfit we last saw when I reviewed their 44% pot-still white, doesn’t sit on its laurels with a self satisfied smirk and think it has achieved something. Not at all. In point of fact it has a couple more whites, both cane juice derived and distilled on their

La Rhumerie de Chamarel, that Mauritius outfit we last saw when I reviewed their 44% pot-still white, doesn’t sit on its laurels with a self satisfied smirk and think it has achieved something. Not at all. In point of fact it has a couple more whites, both cane juice derived and distilled on their

Personally I have a thing for pot still hooch – they tend to have more oomph, more get-up-and-go, more pizzazz, better tastes. There’s more character in them, and they cheerfully exude a kind of muscular, addled taste-set that is usually entertaining and often off the scale. The Jamaicans and Guyanese have shown what can be done when you take that to the extreme. But on the other side of the world there’s this little number coming off a small column, and I have to say, I liked it even more than its pot still sibling, which may be the extra proof or the still itself, who knows.

Personally I have a thing for pot still hooch – they tend to have more oomph, more get-up-and-go, more pizzazz, better tastes. There’s more character in them, and they cheerfully exude a kind of muscular, addled taste-set that is usually entertaining and often off the scale. The Jamaicans and Guyanese have shown what can be done when you take that to the extreme. But on the other side of the world there’s this little number coming off a small column, and I have to say, I liked it even more than its pot still sibling, which may be the extra proof or the still itself, who knows.

Rumaniacs Review #124 | 0803

Rumaniacs Review #124 | 0803 Palate – Meh. Unadventurous. Watery alcohol. Pears, cucumbers in light brine, vanilla and sugar water depending how often one returns to the glass. Completely inoffensive and easy, which in this case means no effort required, since there’s almost nothing to taste and no effort is needed. Even the final touch of lemon zest doesn’t really save it.

Palate – Meh. Unadventurous. Watery alcohol. Pears, cucumbers in light brine, vanilla and sugar water depending how often one returns to the glass. Completely inoffensive and easy, which in this case means no effort required, since there’s almost nothing to taste and no effort is needed. Even the final touch of lemon zest doesn’t really save it.

So let’s try it and see. Nose is, let me state right out, great. Sure, it’s rather rough and ready, spurring and booting around, but nicely rich and deep with initial aromas of butterscotch, caramel, brine, molasses. A nice dry and dusty old cardboard smell is exuded, and then a whiff of rotten fruits – and, as the Jamaicans have taught us, this is not necessarily a bad thing – to which is gradually added a fruity tinned cherry syrup, coconut shavings and vanilla. A few prunes and ripe peaches. Hints of glue, brine, humus and olive oil. It smells both musky and sweet, with anise popping in and out like a jack in the box. Glue, brine, humus and olive oil. So all in all, a lot going on in there, all nicely handled.

So let’s try it and see. Nose is, let me state right out, great. Sure, it’s rather rough and ready, spurring and booting around, but nicely rich and deep with initial aromas of butterscotch, caramel, brine, molasses. A nice dry and dusty old cardboard smell is exuded, and then a whiff of rotten fruits – and, as the Jamaicans have taught us, this is not necessarily a bad thing – to which is gradually added a fruity tinned cherry syrup, coconut shavings and vanilla. A few prunes and ripe peaches. Hints of glue, brine, humus and olive oil. It smells both musky and sweet, with anise popping in and out like a jack in the box. Glue, brine, humus and olive oil. So all in all, a lot going on in there, all nicely handled.

And what a rum it was. I don’t know what ester levels it had, but my first note was “a lot!”. I mean, it was massive. Pencil shavings and glue. Lots of it. Musky, dry, cardboard and damp sawdust. Some rotting fruit (was that dunder they were using?) and also rubber and furniture polish slapped on enough uncured greenheart to rebuild the Parika stelling, twice. The fruitiness – sharp! – of tart apples, green grapes, passion fruit, overripe oranges and freshly peeled tangerines. Florals and crisp light notes, all of it so pungent and bursting that a little breeze through your house and the neighbors would either be calling for a HAZMAT team or the nearest distillery to find out if they had lost their master blender and a still or two.

And what a rum it was. I don’t know what ester levels it had, but my first note was “a lot!”. I mean, it was massive. Pencil shavings and glue. Lots of it. Musky, dry, cardboard and damp sawdust. Some rotting fruit (was that dunder they were using?) and also rubber and furniture polish slapped on enough uncured greenheart to rebuild the Parika stelling, twice. The fruitiness – sharp! – of tart apples, green grapes, passion fruit, overripe oranges and freshly peeled tangerines. Florals and crisp light notes, all of it so pungent and bursting that a little breeze through your house and the neighbors would either be calling for a HAZMAT team or the nearest distillery to find out if they had lost their master blender and a still or two.