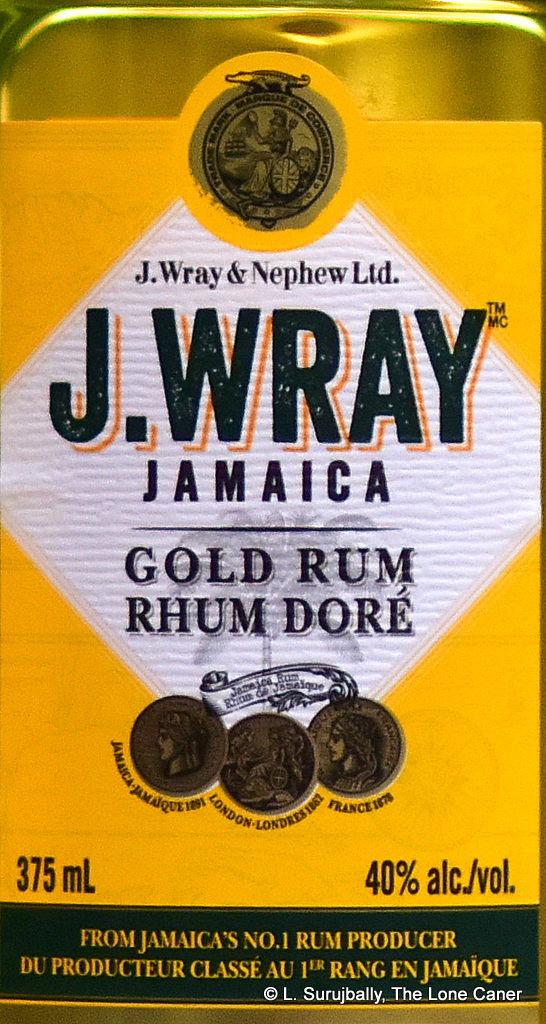

At the opposite end of the scale from the elegant and complex mid-range rum of the Appleton 12 year old – a Key Rum in its own right – lies that long-standing rum favourite of proles and puritans, princes and peasants — the rough ‘n’ tough, cheerfully cussin’ and eight-pack powerful rippedness of the J. Wray & Nephew White overproof, an unaged white rum bottled at a barely bearable 63%, and whose screaming yellow and green label is a fixture in just about every bar around the world I’ve ever been in and escorted out of, head held high and feet held higher.

This is a rum that was one of the first I ever wrote about back in the day when I wasn’t handing out scores, a regular fixture on the cocktail circuit, and an enormously popular rum even after all these years. It sells like crazy both locally and in foreign lands, is bought by poor and rich alike, and no-one who’s ever penned a rum review could dare ignore it (nor should they). I don’t know what its sales numbers are like, but I honestly believe that if one goes just by word of mouth, online mentions and perusal of any bar’s rumshelf, then this must be one of the most well regarded Jamaican (or even West Indian) rums on the planet, as well as one of the most versatile.

Even in its home country the rum has enormous street cred. Like the Guyanese Superior High Wine, it’s a local staple of the drinking scene and supposedly accounts for more than three quarters of all rum sold in Jamaica, and it is tightly woven into the entire cultural fabric of the island. It’s to be found at every bottom-house lime, jump-up or get-together. Every household – expatriate or homeboys – has a bottle taking up shelf space, for pleasure, for business, for friends or for medicinal purposes. It has all sorts of social traditions: crack a bottle and immediately you pour a capful on the ground to return some to those who aren’t with you. Have a housewarming, and grace the floor with a drop or two; touch of the rheumatiz? – rub dem joints with a shot; mek a pickney…put a dab ‘pon he forehead if he sick; got a cold…tek a shot and rub a shot. And so on.

This is not even counting its extraordinary market penetration in the tiki and bar scene (Martin Cate remarked that the White with Ting is the greatest highball in the world). There aren’t many rums in the world which have such high brand awareness, or this kind of enduring popularity across all strata of society. Like the Appleton 12, it almost stands in for all of Jamaica in a way all of its competitors, old and new, seek to emulate. What’s behind it? Is it the way it smells, the way it tastes? Is it the affordable price, the strength? The marketing? Because sure as hell, it ranks high in all the metrics that make a rum visible and appreciated, and that’s even with the New Jamaicans from Worthy park and Hampden snapping at its heels.

Coming back to it after so many years made me remember something of its fierce and uncompromising nature which so startled me back in 2010. It’s a pot and column still blend (and always has been), yet one could be forgiven for thinking that here, the raw and rank pot-still hooligan took over and kicked column’s battie. It reeked of glue and acetones mixed up with a bit of gasoline good only for 1950s-era Land Rovers. What was interesting about it was the pungent herbal and grassy background, the rotting fruits and funky pineapple and black bananas, flowers, sugar water, smoke, cinnamon, dill, all sharp and delivered with serious aggro.

Taste wise, it was clear that the thing was a mixing agent, far too sharp and flavourful to have by itself, though I know most Islanders would take it with ice and coconut water, or in a more conventional mix. It presented rough and raw and joyous and sweaty and was definitely not for the meek and mild of disposition, wherein lay its attraction — because in that fierce uniqueness of profile lay the character which we look for in rums we remember forever. Here, that was conveyed by a sharp and powerful series of tastes – rotten fruit (especially bananas), orange peel, pineapples, soursop and creamy tart unsweetened fresh yoghurt. There was something of the fuel-reek of a smoky kerosene stove floating around, cloves, licorice, peanut, mint, bitter chocolate. It was a little dry, and had no shortage of funk yet remained clearly separable from Hampden and Worthy Park rums, and reminded me more of a Smith & Cross or Rum Fire, especially when considering the long, dry, sharp finish with its citrus and pineapple and wood-chip notes that took the whole experience to its long and rather violent (if tasty) conclusion.

So maybe it’s all of these things I wrote about – taste, price, marketing, strength, visibility, reputation. But unlike many of the key rums in this series, it remains fresh and vibrant year in and year out. I would not say it’s a gateway rum like the Pusser’s 15 or the Diplo Res Ex or the El Dorado 21, those semi-civilized drinks which introduce us to the sippers and which we one day move beyond. It exists at the intersection of price and quality and funk and taste, and skates that delicate line between too much and too little, too rough and almost-refined. You can equally have it in a high-class bar in Manhattan, or from cheap plastic tumblers with Ting while bangin’ down de dominos in the sweltering heat of a Trenchtown yard. In its appeal to all the classes of society that choose it, you can see a Key Rum in action: and for all these reasons, it remains, even after all the years it’s been available, one of the most popular — even one of the best — rums of its kind ever made, in Jamaica, in the West Indies, or, for that matter, anywhere else.

(#665)(83/100)

Other notes

- Unaged pot and column still blend

- The colours on the label channel the colours of the Jamaican flag

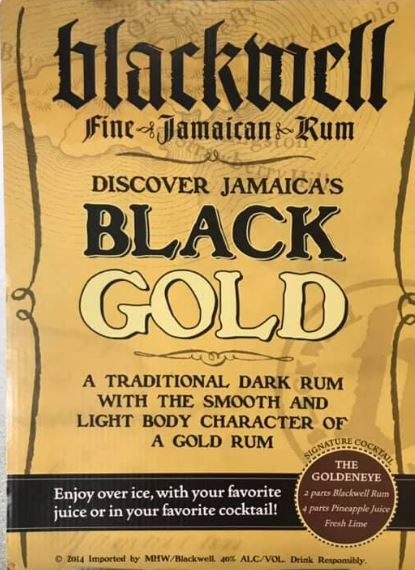

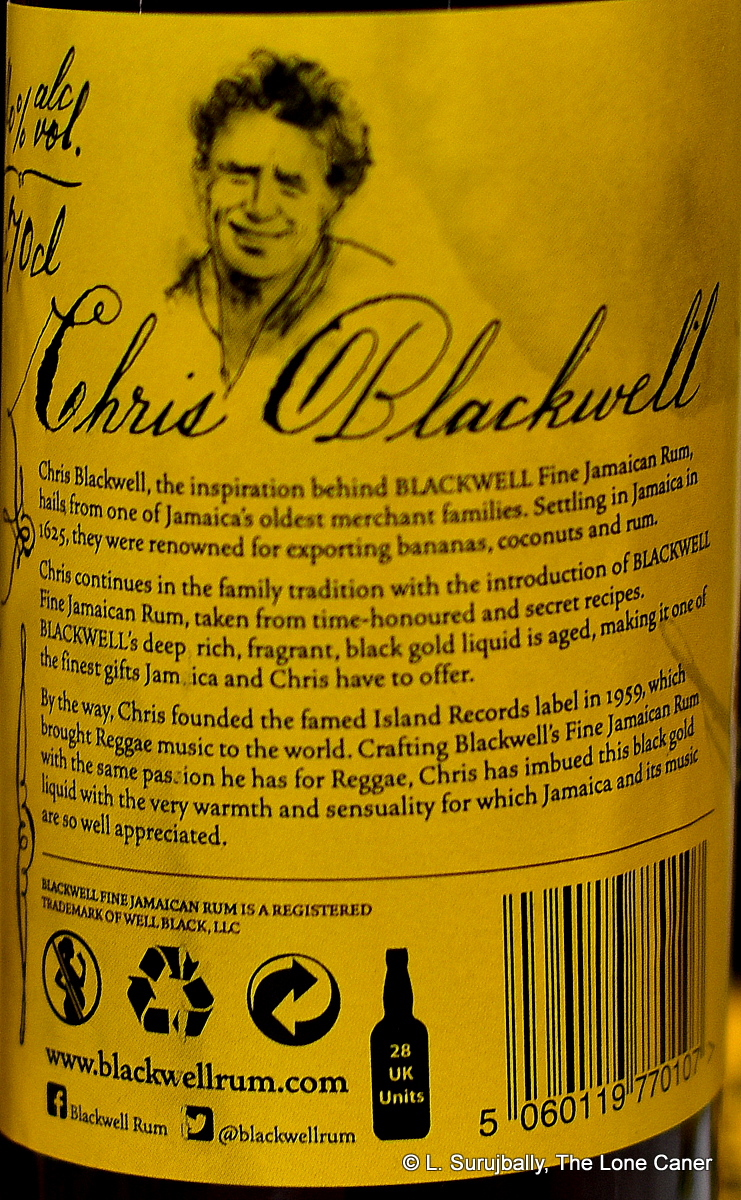

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in  With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

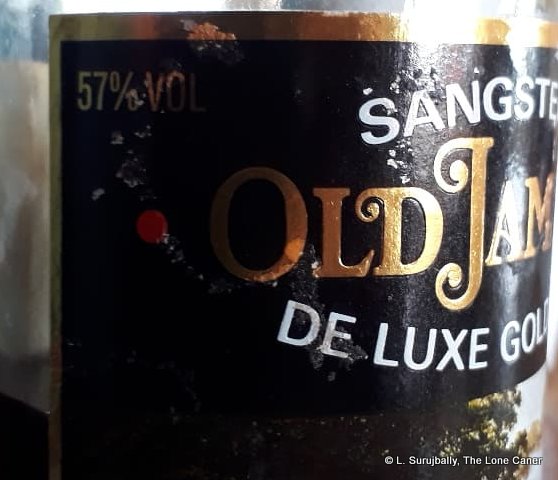

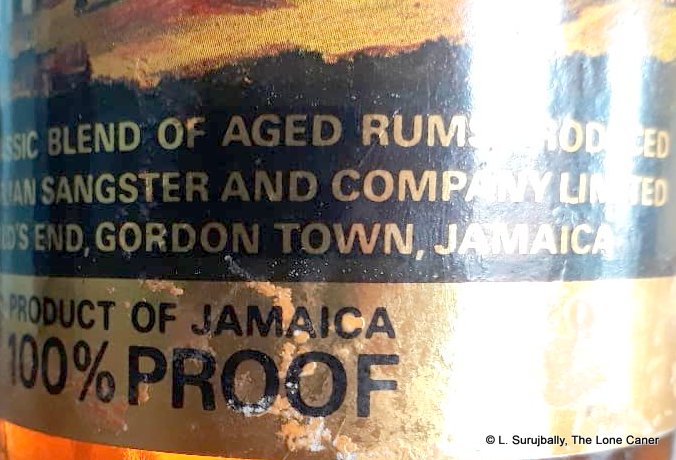

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued.

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued. Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.

Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.  Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones.

Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones.

I make this last observation because of its unrefined nature. Even at standard strength, it noses rather raw and jagged, even harsh. There are initial aromas of light glue, rotten bananas and some citrus, light in tone but sharp in attack. It also smells a little sweet and vanilla-like, with vague florals, apple cider, molasses, dates, peaches and dates, with the slightest rtang of burnt rubber coiling around the back there somewhere. But it sears more than caresses and it’s clear that this is not a lovingly aged product of any kind.

I make this last observation because of its unrefined nature. Even at standard strength, it noses rather raw and jagged, even harsh. There are initial aromas of light glue, rotten bananas and some citrus, light in tone but sharp in attack. It also smells a little sweet and vanilla-like, with vague florals, apple cider, molasses, dates, peaches and dates, with the slightest rtang of burnt rubber coiling around the back there somewhere. But it sears more than caresses and it’s clear that this is not a lovingly aged product of any kind.

Until

Until

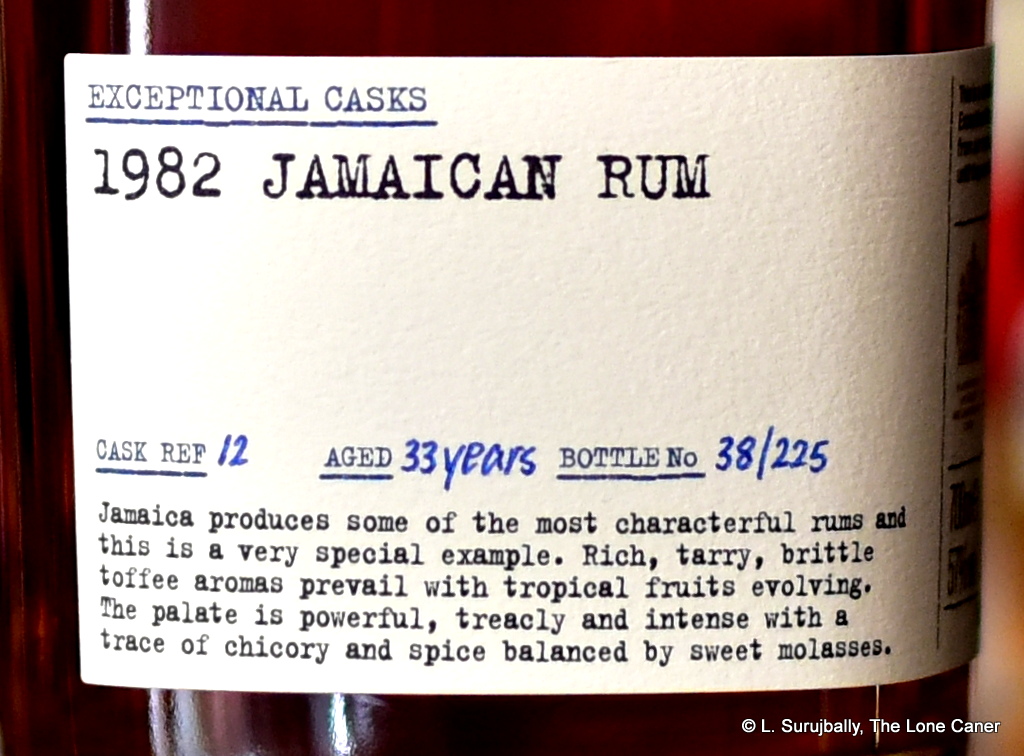

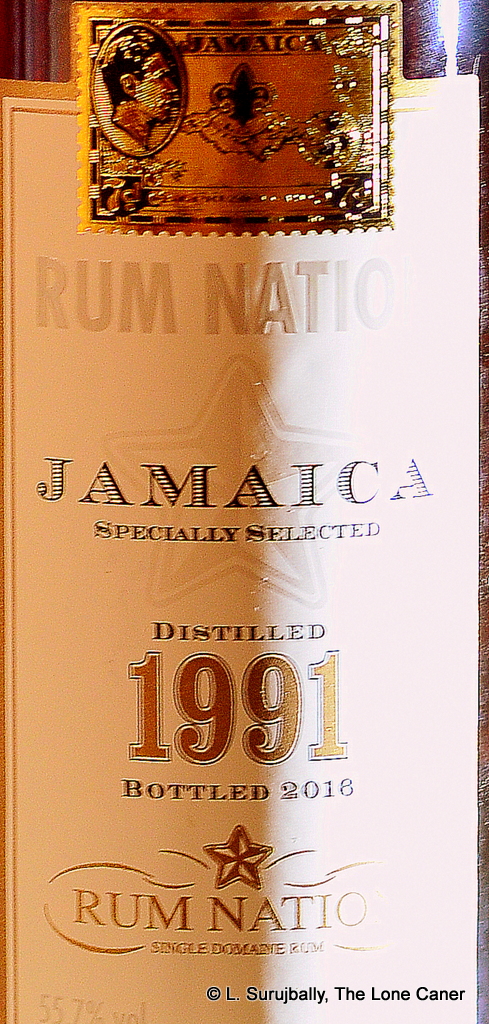

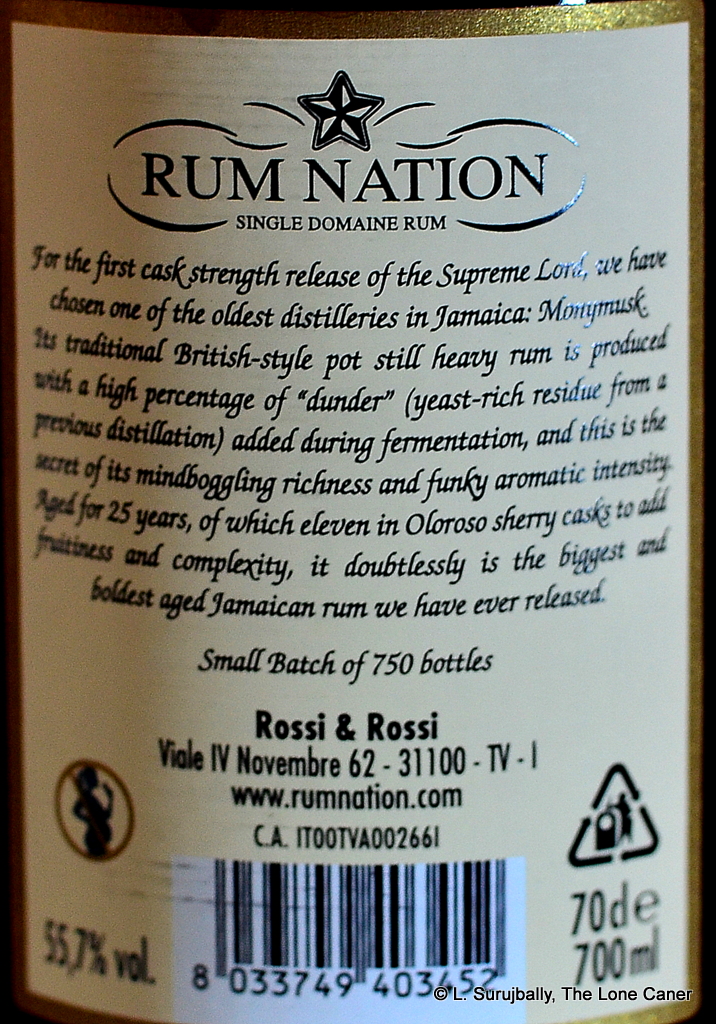

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the  The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

This brings us to the

This brings us to the

In sampling the initial nose of the third rum in the NRJ series, I am not kidding you when I say that I almost fell out of my chair in disbelief. The aroma was the single most rancid, hogo-laden ester bomb I’d ever experienced – I’ve tasted hundreds of rums in my time, but never anything remotely like this (except perhaps the

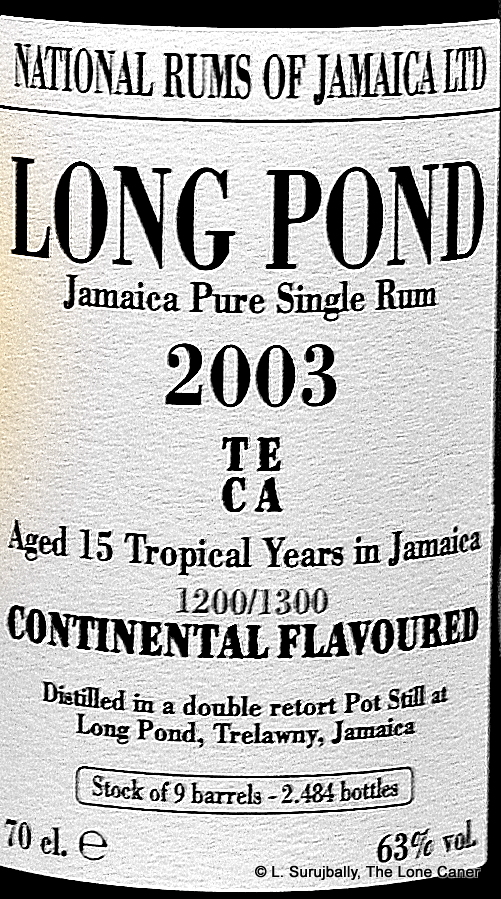

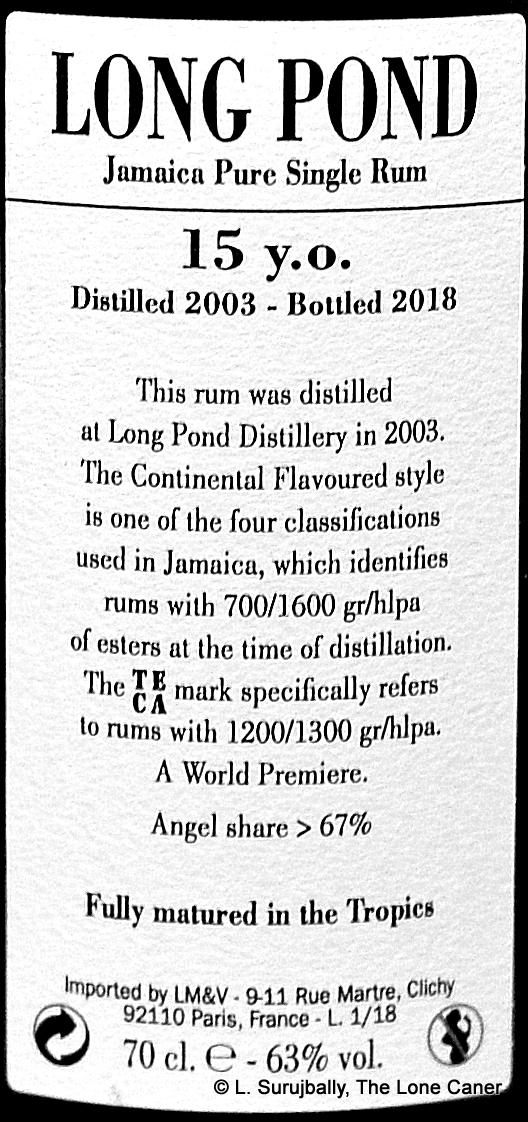

In sampling the initial nose of the third rum in the NRJ series, I am not kidding you when I say that I almost fell out of my chair in disbelief. The aroma was the single most rancid, hogo-laden ester bomb I’d ever experienced – I’ve tasted hundreds of rums in my time, but never anything remotely like this (except perhaps the  In brief, these are all rums from Long Pond distillery, and represent distillates with varying levels of esters (I have elected to go in the direction of lowest ester count → highest, in these reviews). Much of the background has been covered already by two people: the Cocktail Wonk himself with his

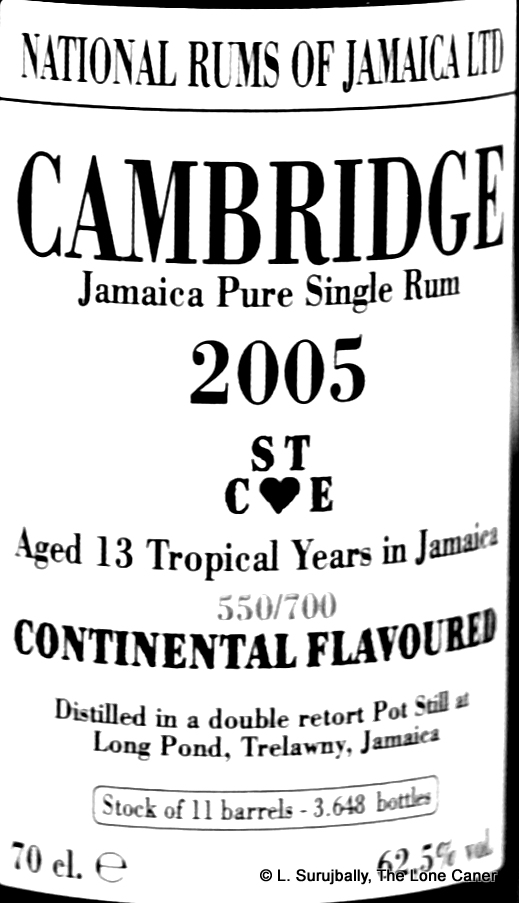

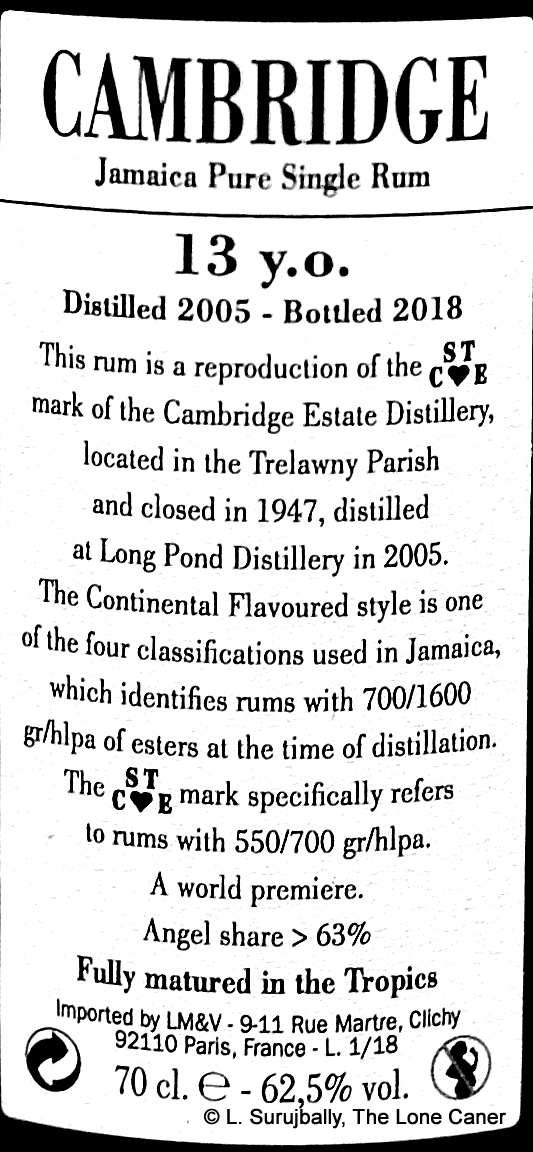

In brief, these are all rums from Long Pond distillery, and represent distillates with varying levels of esters (I have elected to go in the direction of lowest ester count → highest, in these reviews). Much of the background has been covered already by two people: the Cocktail Wonk himself with his

There’s a reason for that. What these esters do is provide a varied and intense and enormously boosted flavour profile, not all of which can be considered palatable at all times, though the fruitiness and light flowers are common to all of them and account for much of the popularity of such rums which masochistically reach for higher numbers, perhaps just to say “I got more than you, buddy”. Maybe, but some caution should be exercised too, because high levels of esters do not in and of themselves make for really good rums every single time. Still, with Luca having his nose in the series, one can’t help but hope for something amazingly new and perhaps even spectacular. I sure wanted that myself.

There’s a reason for that. What these esters do is provide a varied and intense and enormously boosted flavour profile, not all of which can be considered palatable at all times, though the fruitiness and light flowers are common to all of them and account for much of the popularity of such rums which masochistically reach for higher numbers, perhaps just to say “I got more than you, buddy”. Maybe, but some caution should be exercised too, because high levels of esters do not in and of themselves make for really good rums every single time. Still, with Luca having his nose in the series, one can’t help but hope for something amazingly new and perhaps even spectacular. I sure wanted that myself. These are definitions of ester counts, and while most rums issued in the last ten years make no mention of such statistics, it seems to be a coming thing based on its increasing visibility in marketing and labelling: right now most of this comes from Jamaica, but Reunion’s Savanna also has started mentioning it in its Grand Arôme line of rums. For those who are coming into this subject cold, esters are the chemical compounds responsible for much of a given rum’s flowery and fruity flavours – they are measured in grams per hectoliter of pure alcohol, a hectoliter being 100 liters; a light Cuban style rum can have as little as 20 g/hlpa while an ester gorilla like the DOK can go right up to the legal max of 1600 at which point it’s no longer much of a drinker’s rum, but a flavouring agent for lesser rums. (For good background reading, check out the

These are definitions of ester counts, and while most rums issued in the last ten years make no mention of such statistics, it seems to be a coming thing based on its increasing visibility in marketing and labelling: right now most of this comes from Jamaica, but Reunion’s Savanna also has started mentioning it in its Grand Arôme line of rums. For those who are coming into this subject cold, esters are the chemical compounds responsible for much of a given rum’s flowery and fruity flavours – they are measured in grams per hectoliter of pure alcohol, a hectoliter being 100 liters; a light Cuban style rum can have as little as 20 g/hlpa while an ester gorilla like the DOK can go right up to the legal max of 1600 at which point it’s no longer much of a drinker’s rum, but a flavouring agent for lesser rums. (For good background reading, check out the

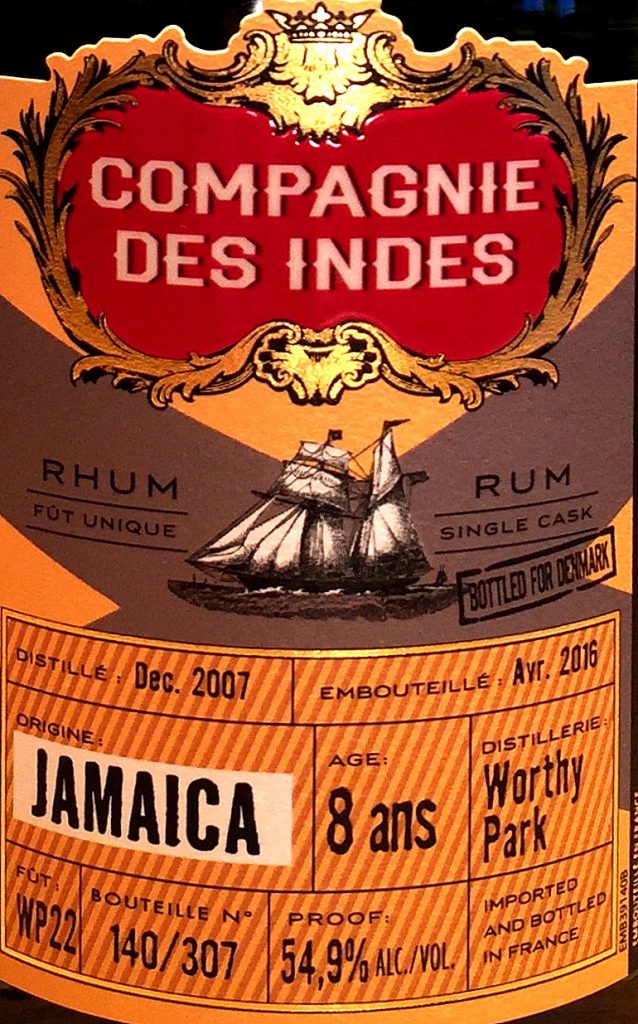

So, given how many Jamaicans are on the scene these days, how does this young, continentally aged 55.9% golden rum fare? Not too shabbily. It’s strong but very approachable, even on the nose, which doesn’t waste any time getting started but announces its ester-rich aromas immediately and with authority: acetone, nail polish and some rubber plus a smell of righteous funk (spoiling fruits, rotten bananas, that kind of thing). Its relative youth is apparent in the uncouth sharpness of the initial aromas, but once one sticks with it, it settles into its own special groove, calms itself down and does a neat little balancing act between sharper scents of citrus, cider, apples, hard yellow mangoes and green grapes, and softer ones of bananas, cumin, vanilla, marshmallows and cloves.

So, given how many Jamaicans are on the scene these days, how does this young, continentally aged 55.9% golden rum fare? Not too shabbily. It’s strong but very approachable, even on the nose, which doesn’t waste any time getting started but announces its ester-rich aromas immediately and with authority: acetone, nail polish and some rubber plus a smell of righteous funk (spoiling fruits, rotten bananas, that kind of thing). Its relative youth is apparent in the uncouth sharpness of the initial aromas, but once one sticks with it, it settles into its own special groove, calms itself down and does a neat little balancing act between sharper scents of citrus, cider, apples, hard yellow mangoes and green grapes, and softer ones of bananas, cumin, vanilla, marshmallows and cloves.