Clement has a stable line of releases that have remained consistent for a long time – the “Bar and Cocktail” range of mixers and the “Classic” mid-level bottlings of the Ambre, Vieux, Canne Bleu and three blancs (40º, 50º, 55º)’. There is also the “Prestige” range consisting of the VSOP, 6YO, 10YO, single cask, Cuvée Homère, the XO, and that famed set of really aged millésimes which comprised the original XO — the 1952, 1970 and 1976. And for those with more money than they know what to do with, the Carafe Cristal, ultimate top of the line for the company but out of the reach of most of us proles.

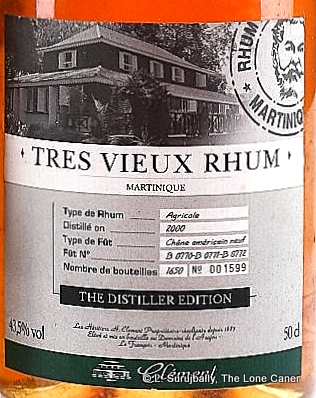

Yet oddly, the trio of The Distiller Edition of their rhums, of which I only ever saw a single example (this one) receives little or no attention at all these days, and has dropped from popular consciousness. It seems to be a small series released around 2007 and sold primarily in Italy, perhaps an unrepeated experiment and included a “Cask Strength” 57.8% edition, and a “Non filtre” 43.5% variation. It suggests a tentative strategy to branch out into craft bottlings that never quite worked out and was then quietly shelved, which may be why it’s not shown on Clement’s website.

Photo courtesy of Sascha Junkert

That said, what are the stats? Of course, this being Clement, it’s from Martinique, AOC-certified, column still, aged in American oak, with 1,650 bottles released at a near standard 43.5% (aside from its blancs, most of the the company ‘s rums are in the mid-forties). The tres vieux appellation tells us it is a minimum of four years old, but my own feeling its that it’s probably grater than five, as I’ve read it was bottled around 2005 or so, which fits in with the somewhat elevated nature of its title and presentation (there’s one reference which says it’s 7-9 years old).

I wouldn’t go so far as to say it’s an awesome undiscovered masterpiece, but it is a cut above the ordinary vieux rhums from Clement which most people have had. It has a dark and sweet nose, redolent of plums and dark red cherries, caramel, vanilla ice cream and a touch of cinnamon dusted mocha. Where’s the herbals? I scribbled in my notes, because those light, white-fruit, grassy notes weren’t really that much in evidence. Mind you, I did also smell olives, brine, flowers and a touch of nutmeg, so it wasn’t as if good stuff wasn’t there.

The palate was about par for the course for a rum bottled at this strength. Initially it felt like it was weak and not enough was going on (as if the profile should have emerged on some kind of schedule), but it was just a slow starter: it gets going with citrus, vanilla, flowers, a lemon meringue pie, plums and blackberry jam. This faded out and is replaced by sugar cane sap, swank and the grassy vegetal notes mixed up with ashes (!!) and burnt sugar. Out of curiosity I added some water , and was rewarded with citrus, lemon-ginger tea, the tartness of ripe gooseberries, pimentos and spanish olives. It took concentration and time to tease them out, but they were, once discerned, quite precise and clear. Still, strong they weren’t (“forceful” would not be an adjective used to describe it) and as expected the finish was easygoing, a bit crisp, with light fruit, fleshy and sweet and juicy, quite ripe, not so much citrus this time. The grassy and herbal notes are very much absent by this stage, replaced by a woody and spicy backnote, medium long and warm

The palate was about par for the course for a rum bottled at this strength. Initially it felt like it was weak and not enough was going on (as if the profile should have emerged on some kind of schedule), but it was just a slow starter: it gets going with citrus, vanilla, flowers, a lemon meringue pie, plums and blackberry jam. This faded out and is replaced by sugar cane sap, swank and the grassy vegetal notes mixed up with ashes (!!) and burnt sugar. Out of curiosity I added some water , and was rewarded with citrus, lemon-ginger tea, the tartness of ripe gooseberries, pimentos and spanish olives. It took concentration and time to tease them out, but they were, once discerned, quite precise and clear. Still, strong they weren’t (“forceful” would not be an adjective used to describe it) and as expected the finish was easygoing, a bit crisp, with light fruit, fleshy and sweet and juicy, quite ripe, not so much citrus this time. The grassy and herbal notes are very much absent by this stage, replaced by a woody and spicy backnote, medium long and warm

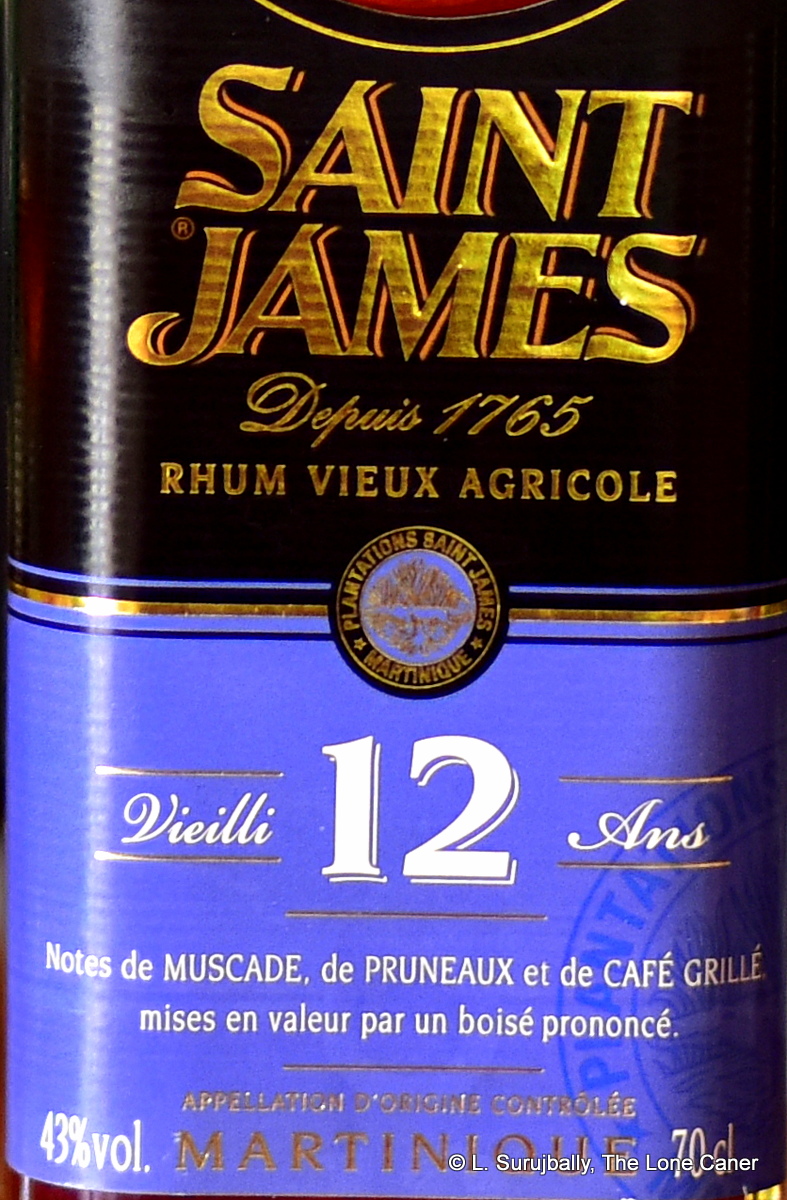

Clement has always been a hard act for me to pin down precisely. Their rhums don’t adhere to any one clear-cut company standard — like, say, Neisson, or Saint James or Damoiseau — and it’s like they always try to sneak something in under the radar to test you, to rock the barrel a bit. That means that peculiar attention has to be paid to appreciate them – they do not reward those in a hurry. I make this point because although I usually feel a sense of frustrated impatience with the weak wispiness of standard proofed rums, some surpass this limitation and bat beyond their strength class, and I think this is one of these…up to a point. The Distiller’s Edition 2000 is not at the level of intensity or quality that so marked the haunting memories evoked by the XO, yet I enjoyed it, and could see the outlines of their better and older rhums take shape in its unformed yet tasty profile, and by no means could I write it off as a loss.

(#738)(84/100)

Other notes

- Over the years, knowing my fondness for stronger rums and the deadening effect these can have on the palate, I have made it a practice to do flights of standard strength first thing in the morning when the palate is fresh and still sensitive to such weaker rums’ profiles.

- When released, the rhum retailed for about €60, but now in 2020, it goes for more than €300…if it can even be found.

- Post will be updated of Clement gets back to me on the background to these limited edition rhums, and what they were created to achieve.

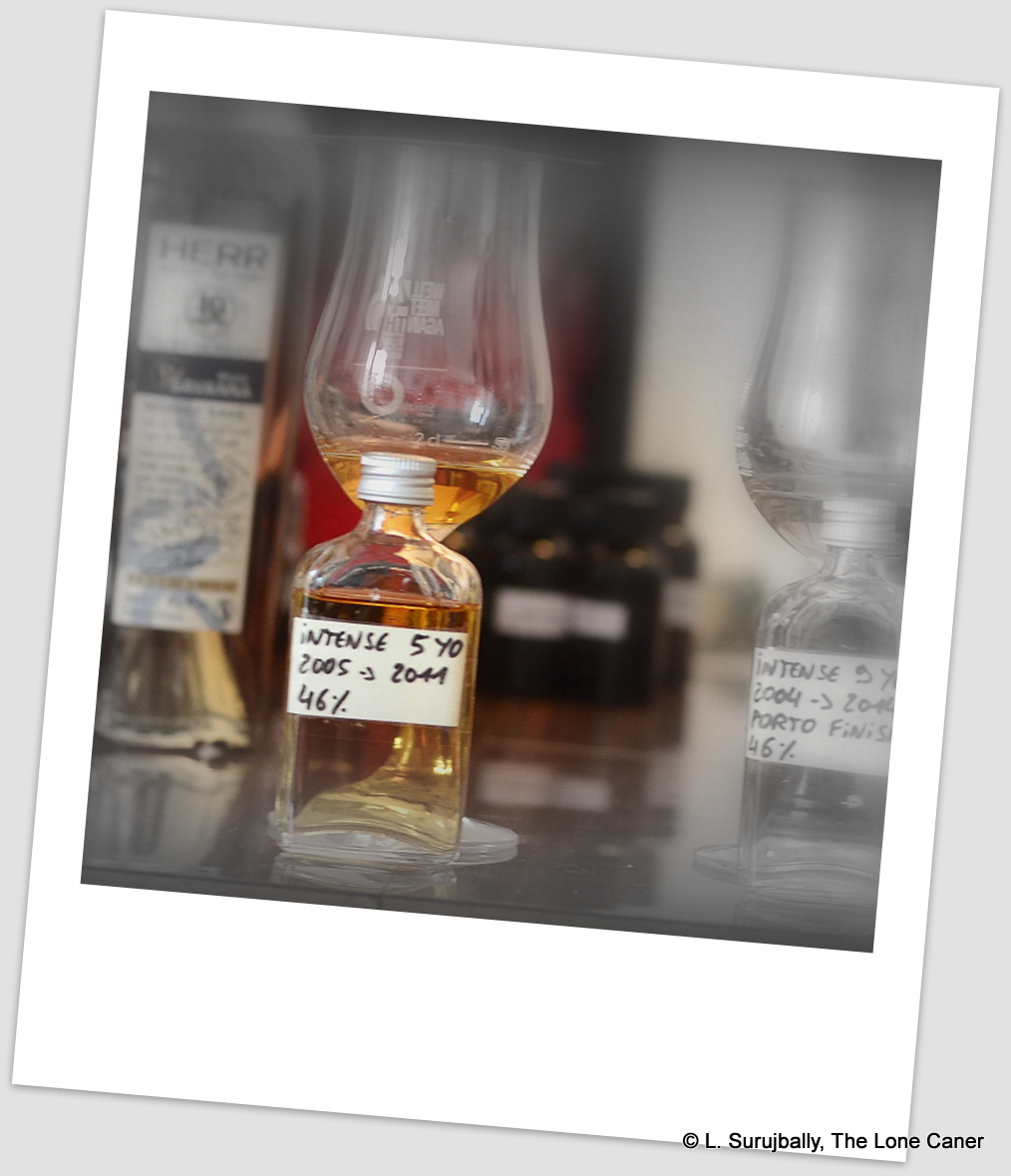

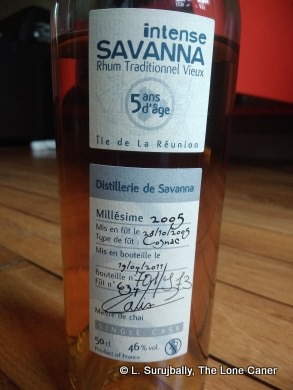

The youth is sensed upon sipping, and it’s an interesting if delicate amalgam. It presents as sharp to begin with, yet the bite climbs back down to gentle very quickly. Some bitter tannins, dampened down before they get a chance to descend into obnoxiousness. Citrus, oranges, nuts, plums, very tart, a bit thin overall to taste…not spotting too much cognac here. Strawberries and pineapples, weak. Nose was better, if not strictly comparable but then, I wasn’t drinking it through my schnozz either. Anyway, good tastes, a little thin, leading to a brisk finish, on the weak side of firm, gone quickly. Tart gooseberries, turmeric, strawberries, some citrus, and a last touch of that honey I enjoyed…it was a nice closing touch.

The youth is sensed upon sipping, and it’s an interesting if delicate amalgam. It presents as sharp to begin with, yet the bite climbs back down to gentle very quickly. Some bitter tannins, dampened down before they get a chance to descend into obnoxiousness. Citrus, oranges, nuts, plums, very tart, a bit thin overall to taste…not spotting too much cognac here. Strawberries and pineapples, weak. Nose was better, if not strictly comparable but then, I wasn’t drinking it through my schnozz either. Anyway, good tastes, a little thin, leading to a brisk finish, on the weak side of firm, gone quickly. Tart gooseberries, turmeric, strawberries, some citrus, and a last touch of that honey I enjoyed…it was a nice closing touch.

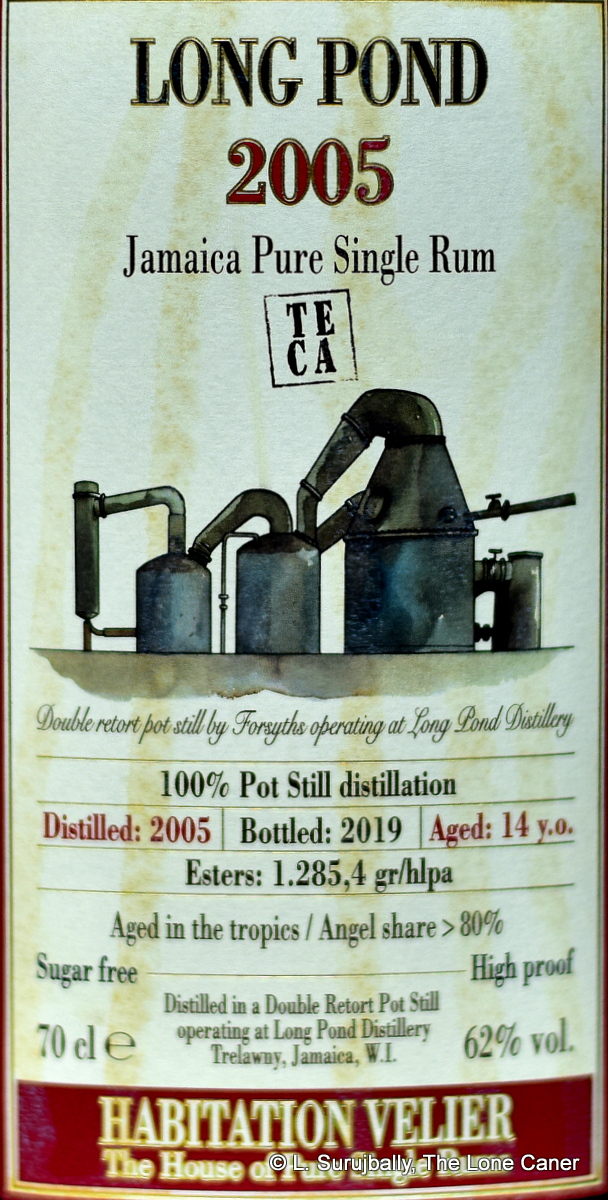

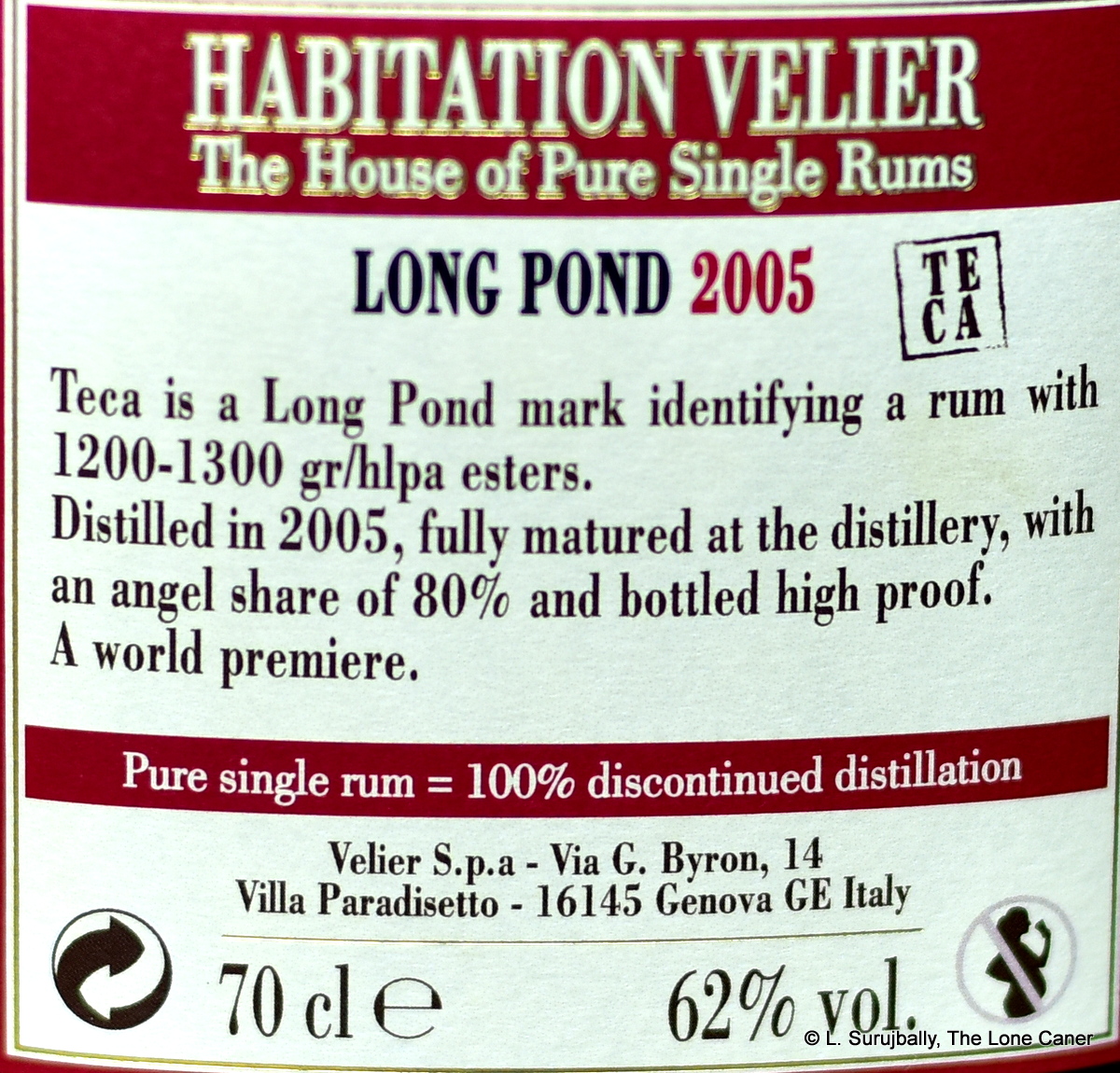

Let’s see if we can’t redress that somewhat. This is a Jamaican rum from Longpond, double pot still made, 62% ABV, 14 years old, and released as one of the pot still rums the Habitation Velier line is there to showcase. I will take it as a given it’s been completely tropically aged. Note of course, the ester figure of 1289.5 gr/hlpa, which is very close to the maximum (1600) allowed by Jamaican law. What we could expect from such a high number, then, is a rum sporting taste-chops of uncommon intensity and flavour, as rounded off by nearly a decade and a half of ageing – now, those statistics made the TECA 2018 detonate in your face and it’s arguable whether that’s a success, but here? … it worked. Swimmingly.

Let’s see if we can’t redress that somewhat. This is a Jamaican rum from Longpond, double pot still made, 62% ABV, 14 years old, and released as one of the pot still rums the Habitation Velier line is there to showcase. I will take it as a given it’s been completely tropically aged. Note of course, the ester figure of 1289.5 gr/hlpa, which is very close to the maximum (1600) allowed by Jamaican law. What we could expect from such a high number, then, is a rum sporting taste-chops of uncommon intensity and flavour, as rounded off by nearly a decade and a half of ageing – now, those statistics made the TECA 2018 detonate in your face and it’s arguable whether that’s a success, but here? … it worked. Swimmingly. So – good or bad? Let’s see if we can sum this up. In short, I believe the 2005 TECA was a furious and outstanding rum on nearly every level. But that comes with caveats. “Fasten your seatbelt” remarked Serge Valentin

So – good or bad? Let’s see if we can sum this up. In short, I believe the 2005 TECA was a furious and outstanding rum on nearly every level. But that comes with caveats. “Fasten your seatbelt” remarked Serge Valentin

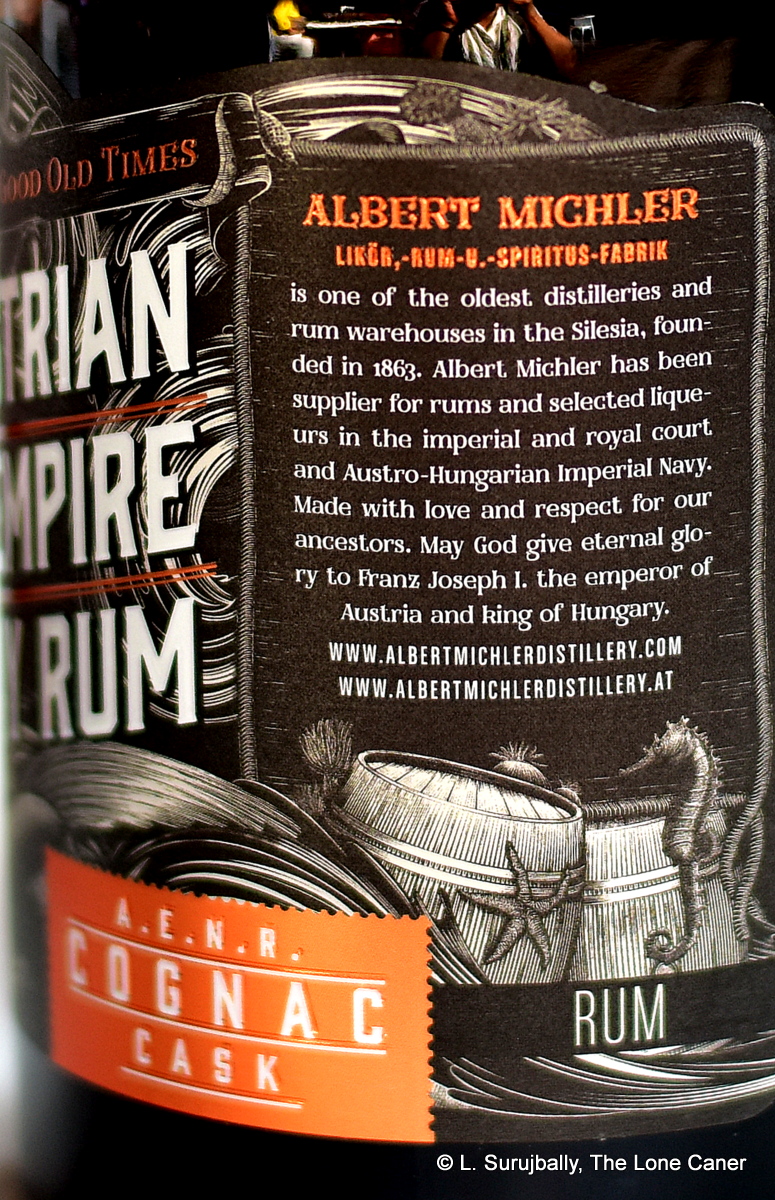

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum

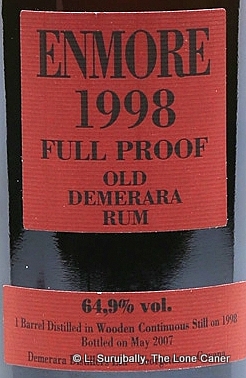

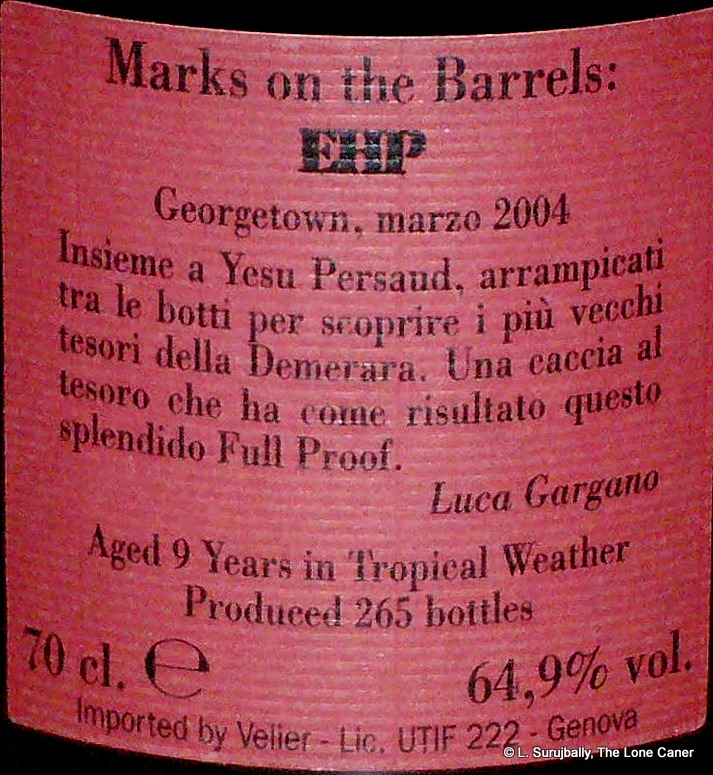

Yet for all that, to ignore it would be a mistake. There’s the irresistible pull of the Old Guyana Demeraras, of that legendary Enmore wooden Coffey still (also known as the “filing cabinet” by wags who’ve seen it), the allure of Velier and their earlier releases which back in the day sold for a hundred or so and now pull down thousands easy (in any currency). How can one resist that? Good or bad, it’s just one of those things one has to try when possible, and for the record, even at that young age, it’s very good indeed.

Yet for all that, to ignore it would be a mistake. There’s the irresistible pull of the Old Guyana Demeraras, of that legendary Enmore wooden Coffey still (also known as the “filing cabinet” by wags who’ve seen it), the allure of Velier and their earlier releases which back in the day sold for a hundred or so and now pull down thousands easy (in any currency). How can one resist that? Good or bad, it’s just one of those things one has to try when possible, and for the record, even at that young age, it’s very good indeed.

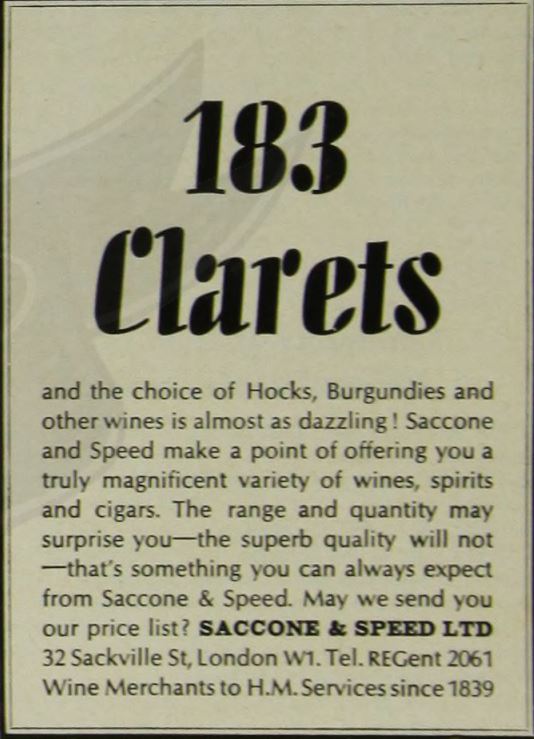

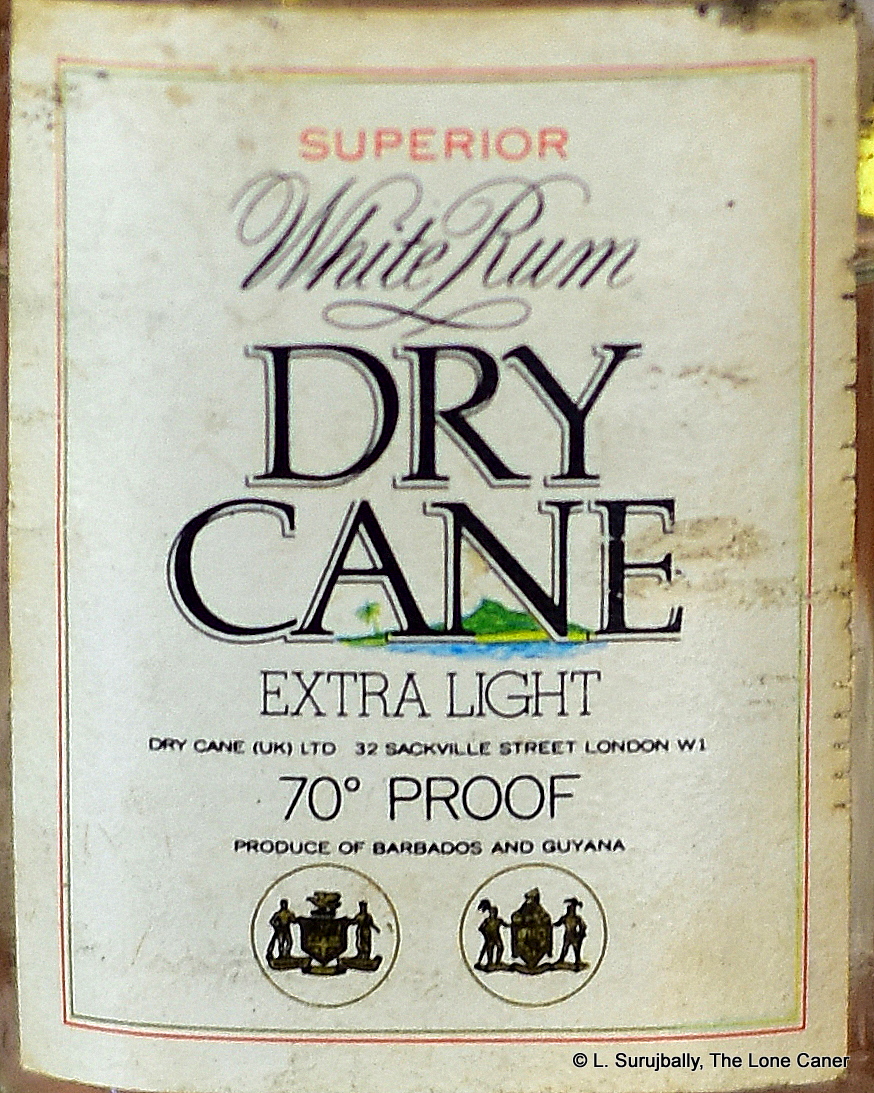

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale. Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.  Anyone from my generation who grew up in the West Indies knows of the scalpel-sharp satirical play “Smile Orange,” written by that great Jamaican playwright, Trevor Rhone, and made into an equally funny film of the same name in 1976. It is quite literally one of the most hilarious theatre experiences of my life, though perhaps an islander might take more away from it than an expat. Why do I mention this irrelevancy? Because I was watching the YouTube video of the film that day in Berlin when I was sampling the Worthy Park series R 11.3, and though the film has not aged as well as the play, the conjoined experience brought to mind all the belly-jiggling reasons I so loved it, and Worthy Park’s rums.

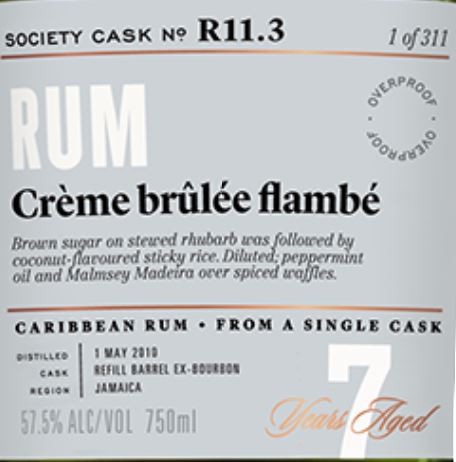

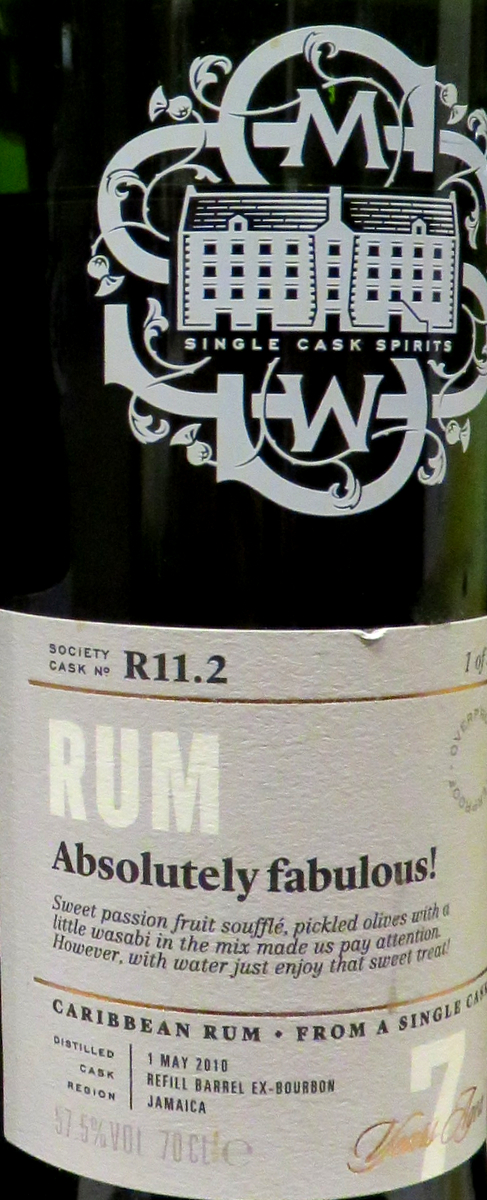

Anyone from my generation who grew up in the West Indies knows of the scalpel-sharp satirical play “Smile Orange,” written by that great Jamaican playwright, Trevor Rhone, and made into an equally funny film of the same name in 1976. It is quite literally one of the most hilarious theatre experiences of my life, though perhaps an islander might take more away from it than an expat. Why do I mention this irrelevancy? Because I was watching the YouTube video of the film that day in Berlin when I was sampling the Worthy Park series R 11.3, and though the film has not aged as well as the play, the conjoined experience brought to mind all the belly-jiggling reasons I so loved it, and Worthy Park’s rums. The distillation run from 2010 must have been a good year for Worthy Park, because the SMWS bought no fewer than seven separate casks from then to flesh out its R11 series of rums (R11.1 through R11.6 were distilled May 1st of that year, with R11.7 in September, and all were released in 2017). After that, I guess the Society felt its job was done for a while and pulled in its horns, releasing nothing in 2018 from WP, and only one more — R11.8 — the following year; they called it “Big and Bountiful” though it’s unclear whether this refers to Jamaican feminine pulchritude or Jamaican rums.

The distillation run from 2010 must have been a good year for Worthy Park, because the SMWS bought no fewer than seven separate casks from then to flesh out its R11 series of rums (R11.1 through R11.6 were distilled May 1st of that year, with R11.7 in September, and all were released in 2017). After that, I guess the Society felt its job was done for a while and pulled in its horns, releasing nothing in 2018 from WP, and only one more — R11.8 — the following year; they called it “Big and Bountiful” though it’s unclear whether this refers to Jamaican feminine pulchritude or Jamaican rums.

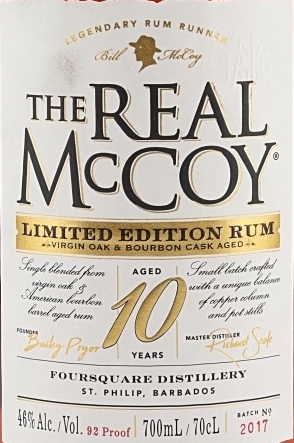

On the palate, the slightly higher strength worked, up to a point. It’s a lot better than 40%, and allowed a certain heft and firmness to brush across the tongue. This then enhanced a melded mishmash of fruits – watermelon, bananas, papaya – plus cocoa butter, coconut shavings in a Bounty chocolate bar, honey and a pinch of salt and vanilla, all of which got shouldered aside by the tannic woodiness. I suspect the virgin oak is responsible for that surfeit, and it made the rum sharper and crisper than those McCoy and Foursquare rums we’re used to, not entirely to the rum’s advantage. The finish summed of most of this – it was dry, rather rough, sharp, and pretty much gave caramel, vanilla, light fruits, and some last tannins which were by now starting to fade. (Subsequent sips and a re-checks over the next few days don’t appreciably change these notes).

On the palate, the slightly higher strength worked, up to a point. It’s a lot better than 40%, and allowed a certain heft and firmness to brush across the tongue. This then enhanced a melded mishmash of fruits – watermelon, bananas, papaya – plus cocoa butter, coconut shavings in a Bounty chocolate bar, honey and a pinch of salt and vanilla, all of which got shouldered aside by the tannic woodiness. I suspect the virgin oak is responsible for that surfeit, and it made the rum sharper and crisper than those McCoy and Foursquare rums we’re used to, not entirely to the rum’s advantage. The finish summed of most of this – it was dry, rather rough, sharp, and pretty much gave caramel, vanilla, light fruits, and some last tannins which were by now starting to fade. (Subsequent sips and a re-checks over the next few days don’t appreciably change these notes).

Colour – Very dark brown

Colour – Very dark brown It sounds strange to say it, but the

It sounds strange to say it, but the

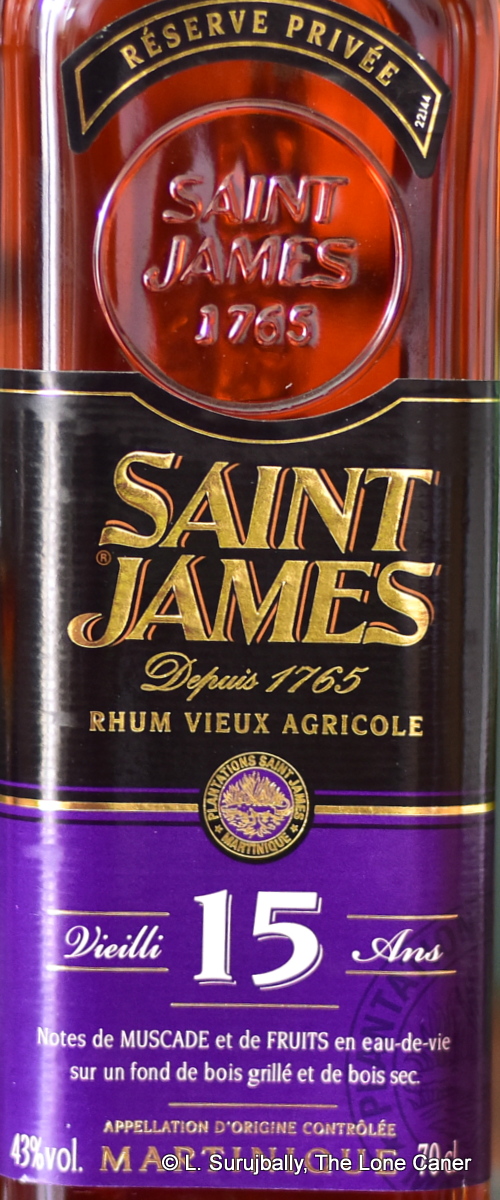

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

To some extent, it has a lighter nose than the luscious

To some extent, it has a lighter nose than the luscious

1423, the Danish indie, has taken this concept a step further with their 2019 release of a Brazil / Barbados carnival — it comprised of 8- and 3-year old Foursquare rums (exact proportions unknown, both column still) to which was added an unaged cachaca from Pirassununga (they make the very popular “51” just outside Sao Paolo), and the whole thing left to age for two years in Moscatel wine casks for two years, before being squeezed out into 323 bottles at 52% ABV.

1423, the Danish indie, has taken this concept a step further with their 2019 release of a Brazil / Barbados carnival — it comprised of 8- and 3-year old Foursquare rums (exact proportions unknown, both column still) to which was added an unaged cachaca from Pirassununga (they make the very popular “51” just outside Sao Paolo), and the whole thing left to age for two years in Moscatel wine casks for two years, before being squeezed out into 323 bottles at 52% ABV.