Photo (c) L’Homme a la Poussette on FB

Rumaniacs Review #136 | 0920

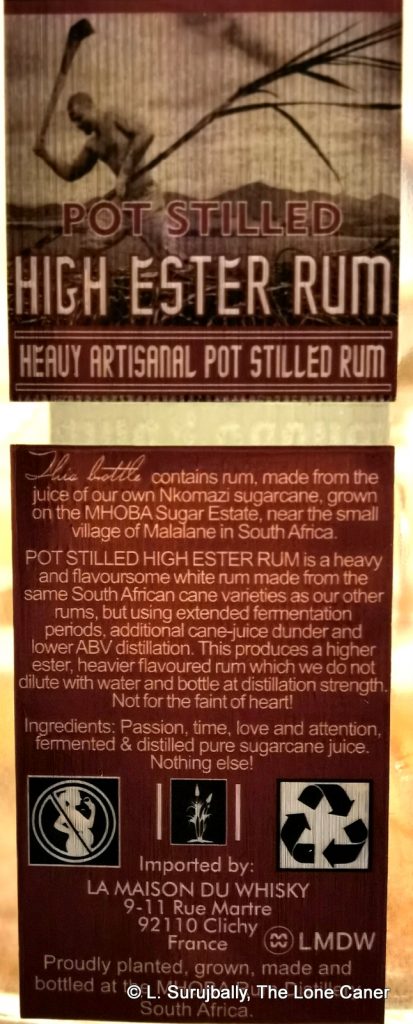

Rhum Jacsi (later named Rhum Jacksi) defies easy categorization and is a research exercise leading down several peculiar rabbit holes. All initial sources agree that the rhum was from Martinique, was made from the 1950s to the 1970s and it is usually to be found at 44% ABV (some later versions were 40%). The source / etymology of the name is not written down but is easily inferred. The distillery of origin is a mystery. The companies involved in its make are the only places one can go and that’s a sufficiently lengthy story to be split off into its own section under these brief tasting notes.

Rum-X is the only place that has any technical specifications: their entry for the rhum states it is from cane juice and done on a column still (of course any such thing as the AOC is undreamed of at this stage of rhum’s evolution), but since attribution is not provided, it’s hard to know who put that entry in, or on what basis. That said, it’s from Martinique, so the statements are not unreasonable given its rhum-making history. Age, unfortunately is a complete zero, as is the distillery of origin. We’ll have to accept we simply don’t know, unless someone who once worked for the brand in the 1960s and 1970s steps forward to clear matters up.

Colour – Gold

Strength – 44%

Photo (c) ebay.fr

Nose – Very herbal and grassy, and is clearly an agricole rhum from cane juice. Lots of vegetables here: carrot juice, wet grass, dark red olives, a touch of pimento, and a nice medley of lighter fruity notes – passion fruit, lime zest, yellow mangoes and an occasional flash of something deeper. It feels better and more voluptuous over time, and I particularly like the aromas of clear citrus juice, soursop, pears, green apples and vanilla.

Palate – Much of the nose transfers seamlessly here, especially the initial tastes of crisp fruits – mangoes, ginnips, ripe apples. Once you’re past this you also get cane sap, sugar water, a slice of lime, a bit of vanilla. Light brininess, pears and apples follow that, balanced off by dark, ripe cherries, syrup and toffee.

Finish – Doesn’t improve noticeably on what came before, and is medium long, but doesn’t get any worse either. Fruits, tart unsweetened yoghurt, miso soup, apple cider, sort of delicate amalgam of sweet and sour overlain with dusky notes of caramel, vanilla and butterscotch.

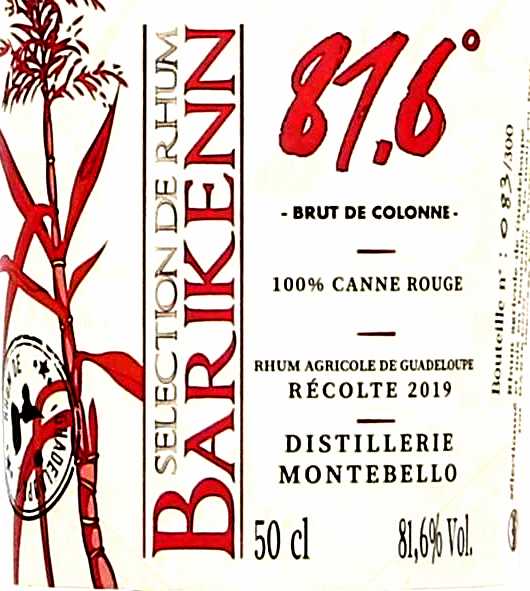

Thoughts – This is a rum I liked, a lot. It’s made from cane juice, but feels deeper and richer than usual, and it reminded me of the old Saint James rhums that used to be heated to 40ºC before fermentation and distillation (in a sort of quasi-Pasteurization process). Not sure of that’s what was done here, and of course the distillery of origin is not known, but It feels half clean agricole and half molasses, and it’s all over delicious.

(86/100) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Historical details

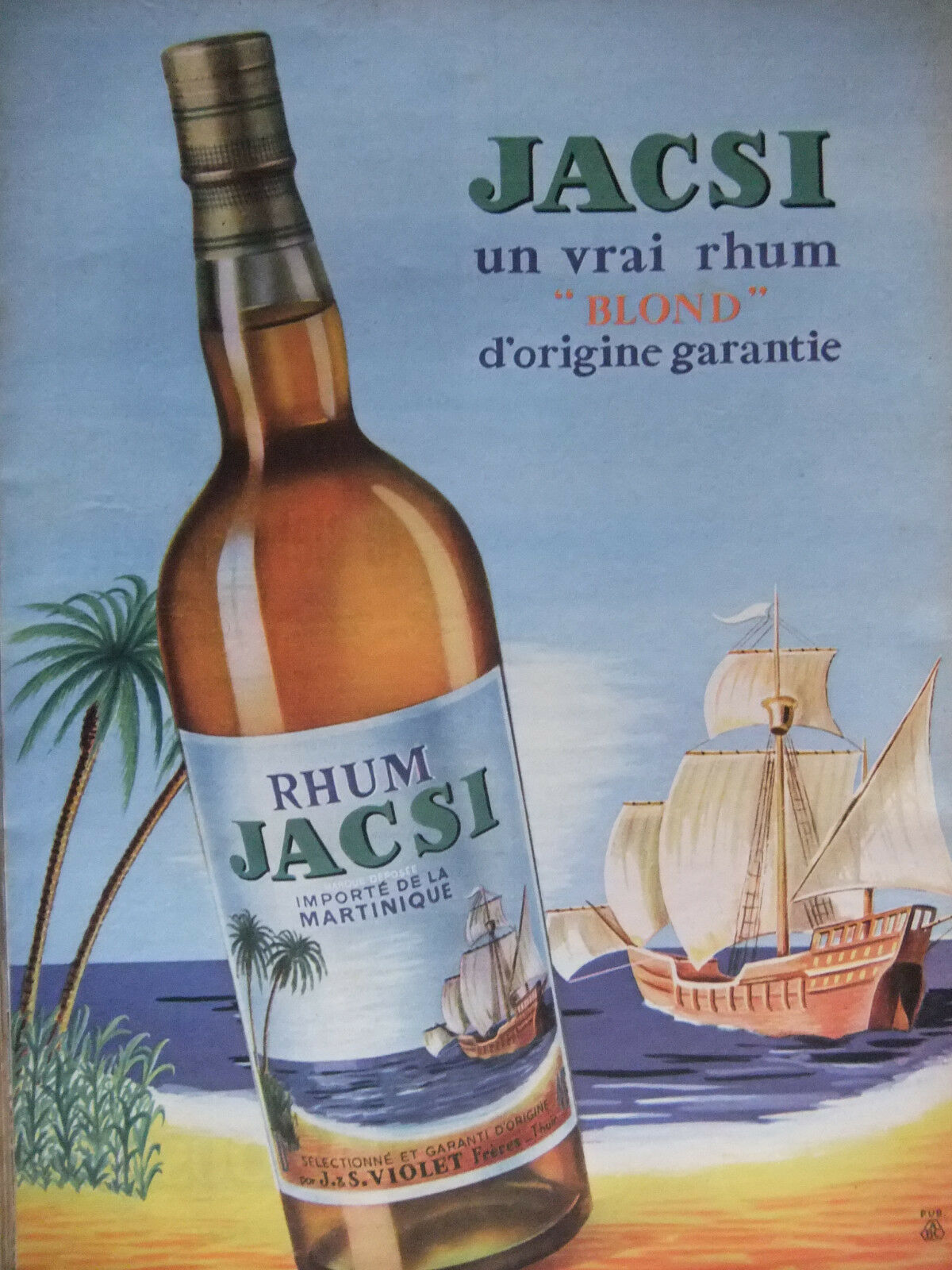

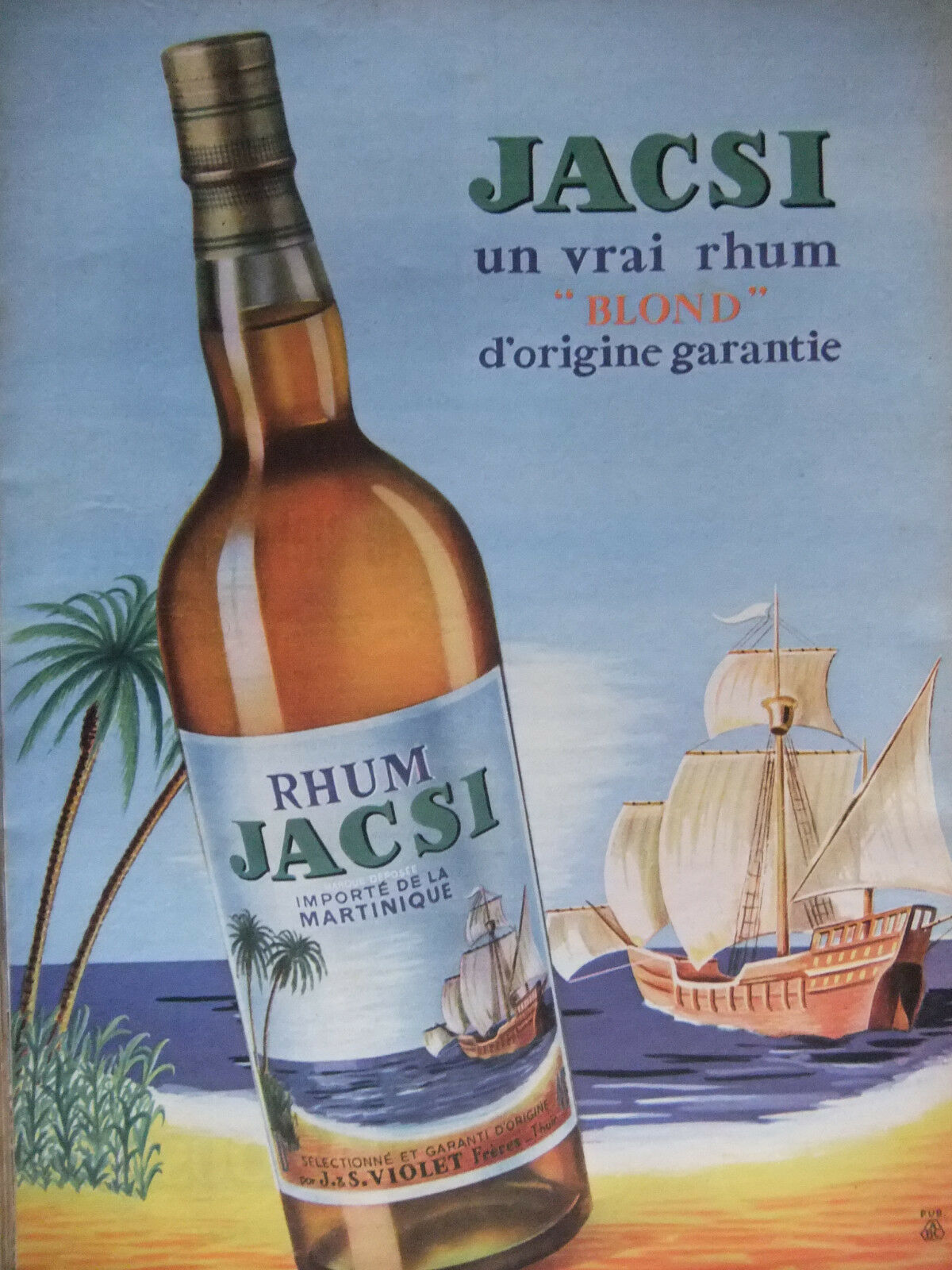

The labels on the bottles that are now being sold (usually at auction) have the notation that it is certified by CDC. But that was just a sort of selection and verification process, guaranteed by Compagnie Dubonnet-Cinzano. Nothing in their history suggests that they — or Pernod, or Ricard who took them over — originated the brand, and so this leads us to another company mentioned on one of the bottles, that of J&S Violet (Freres), which have a far stronger claim to being the ones behind the first Jacsi rhums.

Two brothers named Violet – Pallade and Simon – who were initially itinerant drapers, opened a small shop in the southern French town of Roussillon in 1866 (it is about 40km north of Marseille) and driven by a boom in aperitif wines, they created a blend of their own that combined red wine, mistelles and botanicals…and also quinine (perhaps they also wanted in on the sale of anti malarial drinks that would sell well in tropical colonies, though certainly their marketing of the spirit as a medicinal tonic in pharmacies alleviated problems with existing established vermouth makers as well).

This low-alcohol drink was actually called byrrh – the brothers did not invent the title, just appropriated it as their brand name – and was wildly popular, so, like Dubonnet (see below), the company grew quickly. By the 1890s they had storage facilities for 15 million litres of wine, and by 1910 they employed 750 people and distributed in excess of thirty million litres of byrrh a year – in 1935 Byrrh was France’s leading aperitif brand, apparently. Pallade and Simon passed away by the advent of the first world war, and Lambert’s sons Jacques and Simon (the J&S mentioned on the label and therefore also most likely the Jacques and Simon of the brand name) took over in 1920 – which sets the earliest possible time limit on the Jacsi brand. though I believe it to have been created some decades later.

This low-alcohol drink was actually called byrrh – the brothers did not invent the title, just appropriated it as their brand name – and was wildly popular, so, like Dubonnet (see below), the company grew quickly. By the 1890s they had storage facilities for 15 million litres of wine, and by 1910 they employed 750 people and distributed in excess of thirty million litres of byrrh a year – in 1935 Byrrh was France’s leading aperitif brand, apparently. Pallade and Simon passed away by the advent of the first world war, and Lambert’s sons Jacques and Simon (the J&S mentioned on the label and therefore also most likely the Jacques and Simon of the brand name) took over in 1920 – which sets the earliest possible time limit on the Jacsi brand. though I believe it to have been created some decades later.

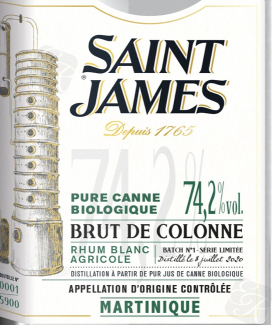

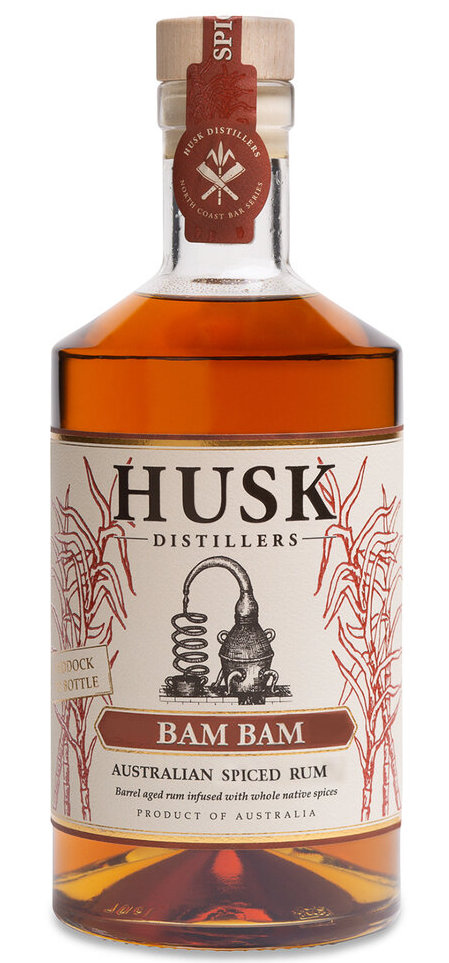

In the post WW2 years, the demand for aperitifs faded as cognacs, brandies, whiskies and light rums surged in popularity. The Violet brothers tried to expand into other spirits at this time, and it was here, in around the mid-fifties, that we start to see the first Jacsi magazine and poster advertisements appear, which is why I can reasonably date the emergence of the Jacsi rhum brand to this time period. Like most print ads of the time, they touted blue waters, tropical beaches, lissome island women, sunshine and the sweet life that could be had for the price of a bottle. It’s very likely that stocks were bought from some broker in the great port of Marseille, just down the road, rather than somebody going to Martinique directly; and the rhums were issued at 44% even then.

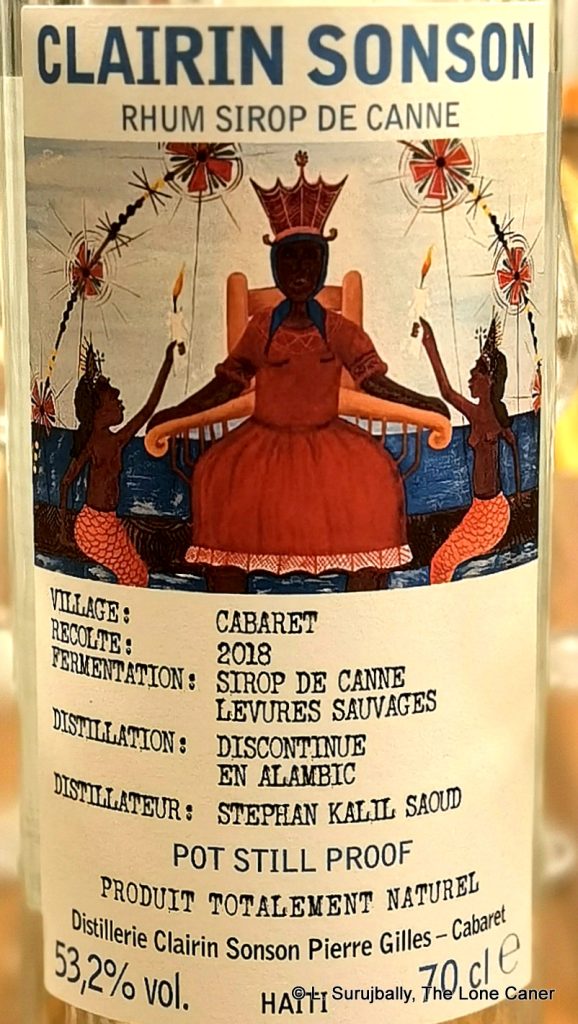

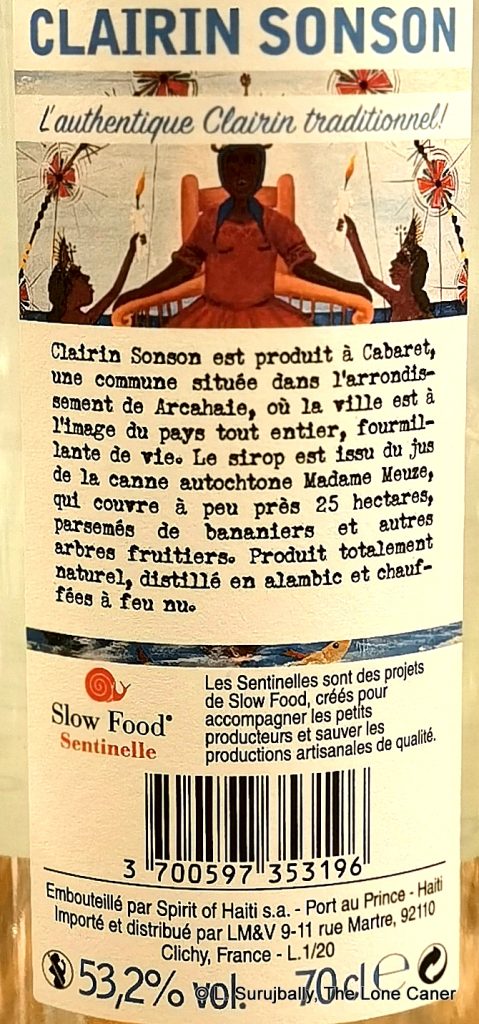

1950s Label with J& Violet Bros. Label. 44%

Alas, this did not help: sales of Byrrh continued to fall, the rhum business was constant but minimal, and in 1961, beset by internecine family squabbles over a path forward, Byrrh sold its entire business, vats, stocks and barrels, to another company involved in liqueurs and aromatic wines and aperitifs – Dubonnet-Cinzano. It is from 1961 that the “selected and guaranteed by CDC” appears on the label of Jacsi branded rhums and the “J&S Violet” quietly exits.

1961 Label – CDC mentioned

So who exactly were CDC? A bottler, certainly, though not a distillery, for these were indie / merchant bottlings, not estate ones. As noted, Jacsi rhums that have turned up for sale in the past few years, all have labels that refer to la Compagnie Dubonnet-Cinzano (CDC). This is a firm which goes back to one Joseph Dubonnet, a Frenchman who created an aperitif modestly called Dubonnet in 1846 in response to a competition organised by the French Government to find a cordial which African legionnaires would drink and colonists could buy, that would disguise the bitter taste of the anti-malarial drug quinine (it therefore served the same purpose as the British gin and tonic in India). This was done at a time when fortified and flavoured wines and liqueurs – especially anises and absinthes – were very popular, so M. Dubonnet’s enterprise found its legs and grew into a large company in very short order.

Late 1960s label, still CDC referenced and at 44%

I could not ascertain for sure whether the Italian vermouth company Cinzano had a stake in Dubonnet or vice versa, but it strikes me as unlikely since they (Cinzano) remained a family enterprise until 1985 – and for now I will simply take the name as a coincidence, or that Dubonnet produced Cinzano under licence. CDC, then, dealt much with vermouths and such flavoured drinks, but like Byrrh, they were caught up in the decline of such spirits in the 1950s. Their own diversification efforts and core sales were good enough to stave off the end, but by the 1970s the writing was on the wall, and they sold out to Pernod Ricard in 1976 – by then the family was ready to sell. Pernod and Ricard had just merged in 1975, and had started an aggressive expansion program, and were willing to buy out CDC to fill out their spirits portfolio, which had no vermouths of note.

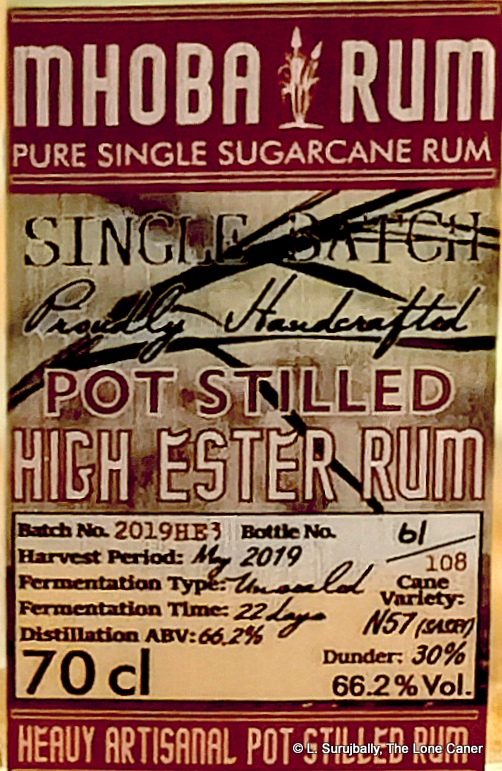

Post-1970s label for 40% version after Pernod Ricard acquisition. 40% ABV and Cusenier name.

By the 1970s, the brand name had been changed to Jacksie, and the “selected and guaranteed by CDC” moniker was retained on the label for a while before being replaced by Cusenier, which was an Argentine spirits maker acquired at the same time by PC – that’s the last reference to the brand and the rhum that can be found. But in an interesting side note, both Dubonnet and Byrrh (now Pernod Absinthe) continue to be made in Thuir, where the facilities of Byrrh once were. Jacsi itself, however, has long since been discontinued and now exists only in these pages and the occasional auction when one goes on sale. For what it’s worth, I think they are amazingly good rums for the prices I’ve seen and the only reason they keep going for low prices is because nothing is known about them. Not any more.

Tasting it continues that odd mix of precision and solidity, and really, the question I am left with is how is a rum dialling in at 50% ABV be this warm and smooth, as opposed to hot and sharp? It’s dry and strops solidly across the palate. Sugar water, ripe freshly sliced apples, cider, lemon zest and nail polish remover, all of which crackles with energy, every note clear and distinct. Lemon zest, freshly mown grass, pears, papaya, red grapefruits and blood oranges, and nicely, lightly sweet and as bright as a glittering steel blade, ending up with a finish that’s dry and sweet and long and dry and really, leaves little to complain about, and much to admire.

Tasting it continues that odd mix of precision and solidity, and really, the question I am left with is how is a rum dialling in at 50% ABV be this warm and smooth, as opposed to hot and sharp? It’s dry and strops solidly across the palate. Sugar water, ripe freshly sliced apples, cider, lemon zest and nail polish remover, all of which crackles with energy, every note clear and distinct. Lemon zest, freshly mown grass, pears, papaya, red grapefruits and blood oranges, and nicely, lightly sweet and as bright as a glittering steel blade, ending up with a finish that’s dry and sweet and long and dry and really, leaves little to complain about, and much to admire.