Introduction

Perhaps it was inevitable. The spirits market has been on a downturn since COVID receded and rum has been hit hard. Several mid range indies have gone under or are having financial woes, while the bigger and well known big name producers – Mount Gay, Appleton, DDL et al – are being forced to do some belt tightening of their own, or trying to expand into newer product niches where the sales are smaller and costs higher, but potential margins are larger. Such new entrants to the field seek to stand out via new production methods, different ageing, or just some difference in branding to distinguish themselves in the premium space. And, in this case, to accentuate the value of terroire.

Mount Gay’s Single Estate bottlings is doing a bit of all of this. Known mostly for blends up and down the value chain, from the Eclipse series to the premium 1703 to the more recent (and upscale) experimentals, finished rums and Master Blender’s series, Mount Gay seems to have taken inspiration from the forceful imagination of their master blender Trudiann Branker and the production team; from the labelling and transparency ethos that have become a new standard; and the desire to move upscale with something at right angles to their more popular mass market releases.

Mount Gay’s Single Estate bottlings is doing a bit of all of this. Known mostly for blends up and down the value chain, from the Eclipse series to the premium 1703 to the more recent (and upscale) experimentals, finished rums and Master Blender’s series, Mount Gay seems to have taken inspiration from the forceful imagination of their master blender Trudiann Branker and the production team; from the labelling and transparency ethos that have become a new standard; and the desire to move upscale with something at right angles to their more popular mass market releases.

What we have, then, is the Single Estate series, which debuted to much fanfare in 2023 and, shorn of all the marketing ballyhoo, is all about terroire and the taste profile of cane and molasses deriving from the island itself (for the benefit of those who are unaware, most Caribbean islands that are not making agricoles import molasses from elsewhere to make their signature rums).

Production Notes

The molasses derives from Mount Gay’s own sugar cane fields, which by itself is a new development, dating back to 2015 when they bought 324 acres of nearby farmland and began growing their own cane there. The acreage isn’t a whole lot – certainly insufficient for their global production output – but it does allow limited special editions like this one to be made.

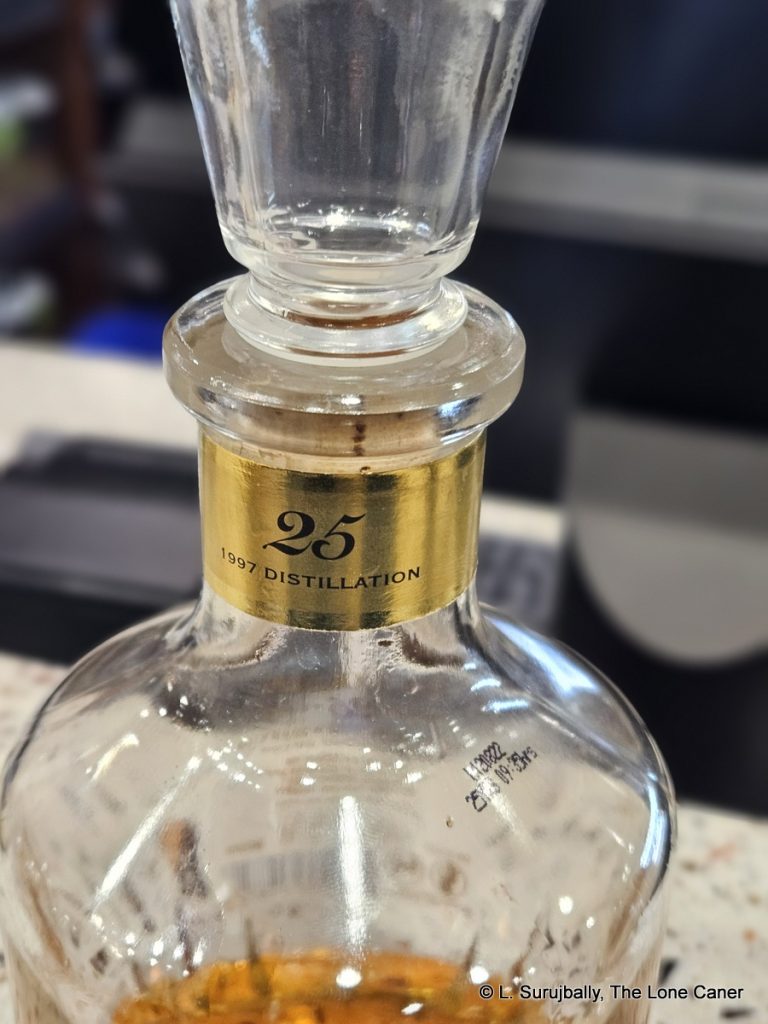

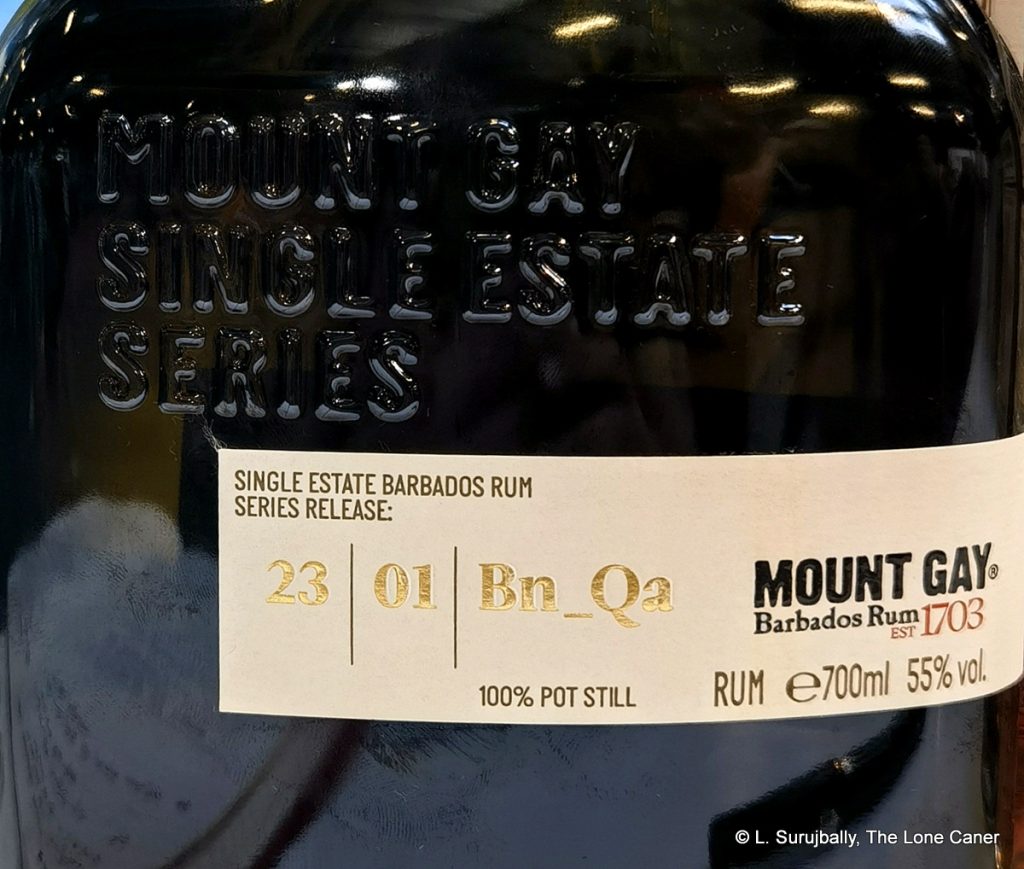

The rum deriving from this stock is the first release in 2023 (as of 2025 there are four), and it’s a blend of 5- and 6-year old rums produced from the 2016 and 2017 harvest, 9 days’ fermentation, 100% pot still, and then ex-bourbon barrel aged, with a final release of this batch, of 55% ABV. The dark decanter, very similar to in shape to the 1703, is made with 70% recycled glass. The outturn is mid range, and varies from release to release: this one, I read on Robbreport, is just over 4,000 bottles total, of which 1200 is allocated to the US (no idea how much Canada got, but I haven’t seen any there yet).

Tasting Notes

At 55% ABV, the aromas are quite firm, and very aggressive right off the bat (in a good way). There are notes of kimchi, golden, light and crisp, almost agricole-like in its clean light aromas. Tawny scents of ginger, tobacco, soursop, lychees, dragon fruit all follow in rapid succession and the real difficulty is in just keeping up with what billows out of the glass. Slightly muskier tones start to creep in – figs, dates, soya sauce, some freshly grated coconut, and overall it smells clean, light, mildly sweet, with just enough sour to perk up the nose and keep you paying attention. Oh and before it’s over, you are also getting green mangoes, tamarind and (I swear I’m not making this up) burnt jerk chicken.

At 55% ABV, the aromas are quite firm, and very aggressive right off the bat (in a good way). There are notes of kimchi, golden, light and crisp, almost agricole-like in its clean light aromas. Tawny scents of ginger, tobacco, soursop, lychees, dragon fruit all follow in rapid succession and the real difficulty is in just keeping up with what billows out of the glass. Slightly muskier tones start to creep in – figs, dates, soya sauce, some freshly grated coconut, and overall it smells clean, light, mildly sweet, with just enough sour to perk up the nose and keep you paying attention. Oh and before it’s over, you are also getting green mangoes, tamarind and (I swear I’m not making this up) burnt jerk chicken.

On the palate, well, it does settle down quite a bit, as if afraid of its own temerity at going off the reservation — and it becomes something much more traditional. Burnt orange peel, vanilla, Worcestershire sauce, green grapes, ashes, char (maybe from charred barrels) and the standard attendants of caramel, toffee, chocolate and maybe a bit of wet coffee grounds make their appearance as well. Even the finish, which is often hit or miss with too many MG rums I’ve tried (including those released by indies), is pretty damned fine, medium long, redolent of citrus, chocolate oranges, toffee, vanilla, nutmeg, and the faintest touch of yogurt and cinnamon sticks.

Wrapping it up, then…

At first blush, which is to say within the first five minutes of tasting it, it’s hard to distinguish it from a true agricole – really! It has that same light, clean, green serpentine clarity to it. It’s only after wrestling it to the ground and ignoring the twisting coils of sweetness and grass, that one sees what it’s really made of – and that’s really, really good.

If it has a weakness is that I don’t actually think it represents the terroire of Barbados generally, or Mount Gay specifically, particularly well, if at all — though I concede this may simply be because we’ve rarely had an opportunity to do so before, given that distilleries on the island mostly import their molasses from elsewhere. I’ve read some reviews that remark on it not really “being all that” for a blend of five and six year old rums, costing as much as it does, which is another fair point. What I did was ignore the cost, ignored the presentation, dispensed with the marketing and promotion, and just looked at the rum as a rum 1. And so, stripped of everything extraneous, putting away any expectations engendered by price or age or reputation … what’s was it like then?

Well, perhaps I’m in a minority here… but I think it’s really kind of marvellous. The nose is complex, the palate is well balanced, the tastes are great and it’s just different enough to enthuse without veering too far from more familiar tastes. Based purely on smell and taste, it’s a very good rum. One can only hope that subsequent editions maintain this level of quality…or exceed it.

(#1135)(88/100) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Other notes

- Video recap link

- I like the label, a lot. There’s something quite simple and elegant about the design, and what the label itself doesn’t say, is available from the QR code that takes you to Mount Gay’s dedicated page for the rum, and there you are greeted with a plethora of information that is all we could ever want. Kudos to MG for providing it all.

- Note the alphanumeric code that’s so prominently displayed. 23 | 01 | Bn_Qa. The 23 stands for year of release (not distillation), the 01 is the Batch number and the Bn_Qa stands for “bourbon barrels” and American oak barrels, or Quercus Alba. As a person who believes the rumworld should develop a global, generic, easy to understand labelling code that’s consistent around the world for all producers from all countries, I love this kind of thing, and believe that it could, and should – even must – be implemented and expanded. Matt Pietrek wrote an interesting article on the subject which may be worth re-reading.

Opinion

I believe that yes, the cost of the bottle is too high. Don’t get me wrong, as a bean counter and numbers guy, I understand that the costs of production have to be recouped, margins maintained. But man, the current price for £350 in the UK and something equivalent in Europe, four hundred bucks in the US… for a rum less than ten years old, even dressed up so prettily, that’s a hard sell.

Given Remy Cointreau’s rather deep pockets, I would have expected them to okay a marginal or even breakeven price point, just to win more rapid acceptance. Maybe they could have let their lower tier brand items subsidize it for a while – so, say, £200 would not be out to lunch for something of such limited release, strength and provenance.

Connoisseurs who know why the price is at that level, would snap it up. But the current tag is simply unconscionable, no matter the logic and economic reality. The danger of setting such and exorbitant charge on the consumer is that too many will be put off by it, too few will buy it, and that might kill this series before it finds serious acceptance. That leaves only collectors, and for the rest of us proles, well, we’re deprived of something really quite special.