Rumaniacs Review #116 | 0732

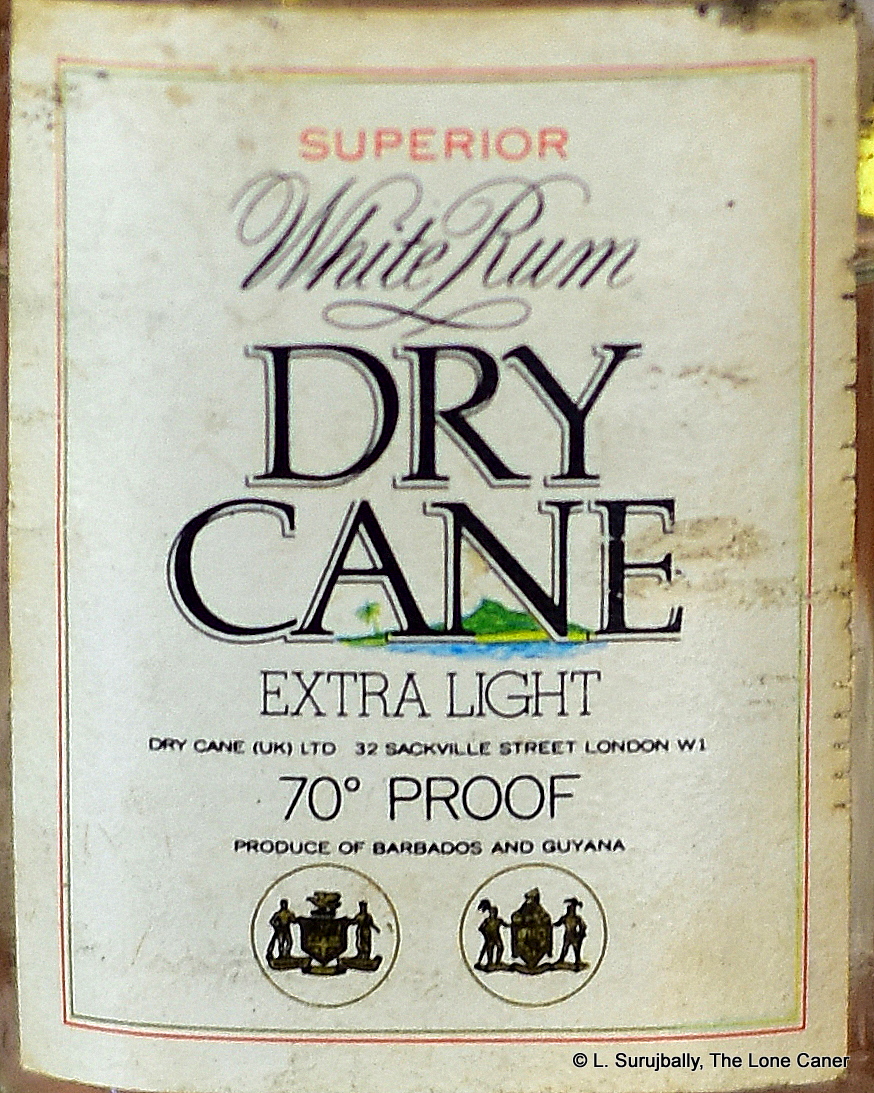

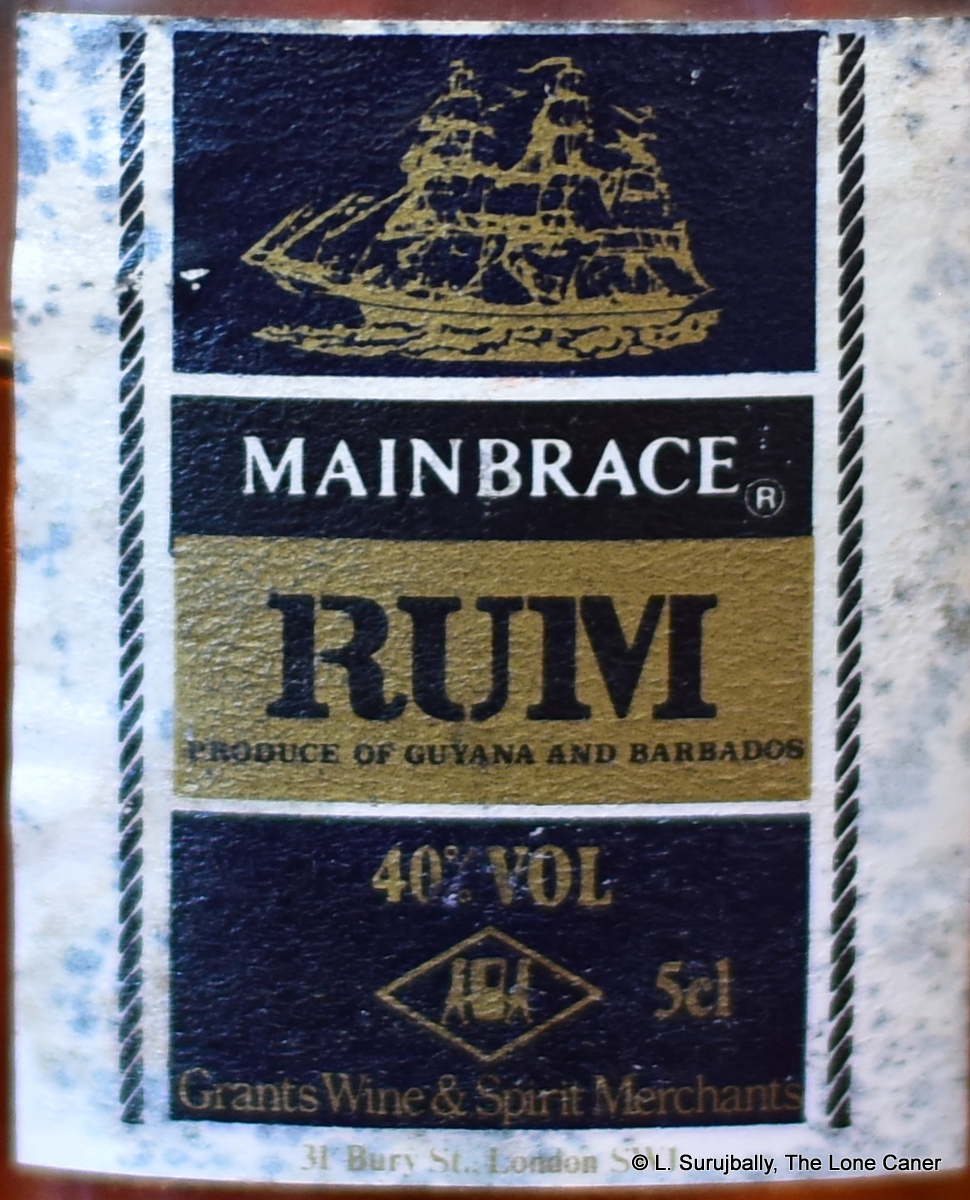

Dry Cane UK had several light white rums in its portfolio – some were 37.5% ABV, some were Barbados only, some were 40%, some Barbados and Guyanese blends. All were issued in the 1970s and maybe even as late as the 1980s, after which the trail goes cold and the rums dry up, so to speak. This bottle however, based on photos on auction sites, comes from the 1970s in the pre-metric era when the strength of 40% ABV was still referred to as 70º in the UK. It probably catered to the tourist, minibar, and hotel trade, as “inoffensive” and “unaggressive” seem to be the perfect words to describe it, and II don’t think it has ever made a splash of any kind.

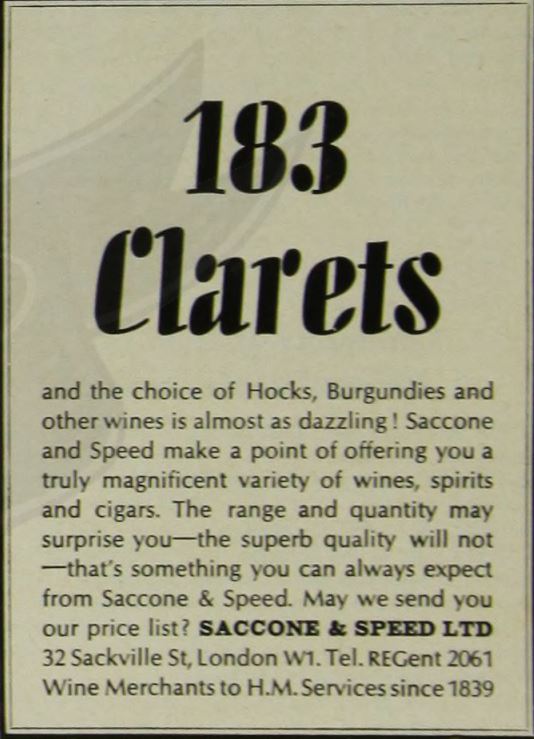

As to who exactly Dry Cane (UK) Ltd were, let me save you the trouble of searching – they can’t be found. The key to their existence is the address of 32 Sackville Street noted on the label, which details a house just off Piccadilly dating back to the 1730s. Nowadays it’s an office, but in the 1970s and before, a wine, spirits and cigar merchant called Saccone & Speed (established in 1839) had premises there, and had been since 1932 when they bought Hankey Bannister, a whisky maker, in that year. HB had been in business since 1757, moved to Sackville Street in 1915 and S&S just took over the premises. Anyway, Courage Breweries took over S&S in 1963 and handed over the spirits section of the UK trade to another subsidiary, Charles Kinloch – who were responsible for that excellent tipple, the Navy Neaters 95.5º we have looked at before (and really enjoyed).

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

Colour – White

Strength – 40% ABV

Nose – Light and sweet; toblerone, almonds, a touch of pears. Its watery and weak, that’s the problem with it, but interestingly, aside from all the stuff we’re expecting (and which we get) I can smell lipstick and nail polish, which I’m sure you’ll admit is unusual. It’s not like we find this rum in salons of any kind.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Finish – Short, dreary, light, simple. Some sugar again and something of a vanilla cake, but even that’s reaching a bit.

Thoughts – Well, one should not be surprised. It does tell you it’s “extra light”, right there on the label; and at this time in rum history, light blends were all the rage. It is not, I should note, possible to separate out the Barbadian from the Guyanese portions. I think the simple and uncomplex profile lends credence to my theory that it was something for the hospitality industry (duty free shops, hotel minibars, inflight or onboard boozing) and served best as a light mixing staple in bars that didn’t care much for top notch hooch, or didn’t know of any.

(74/100)

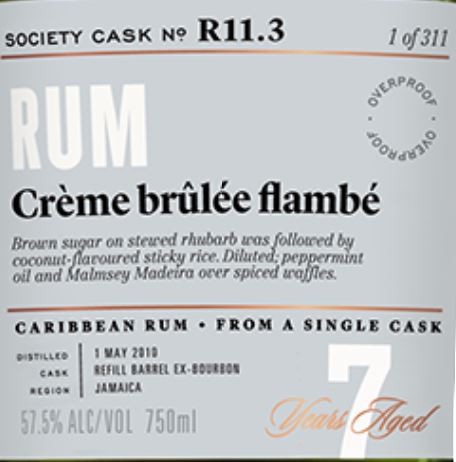

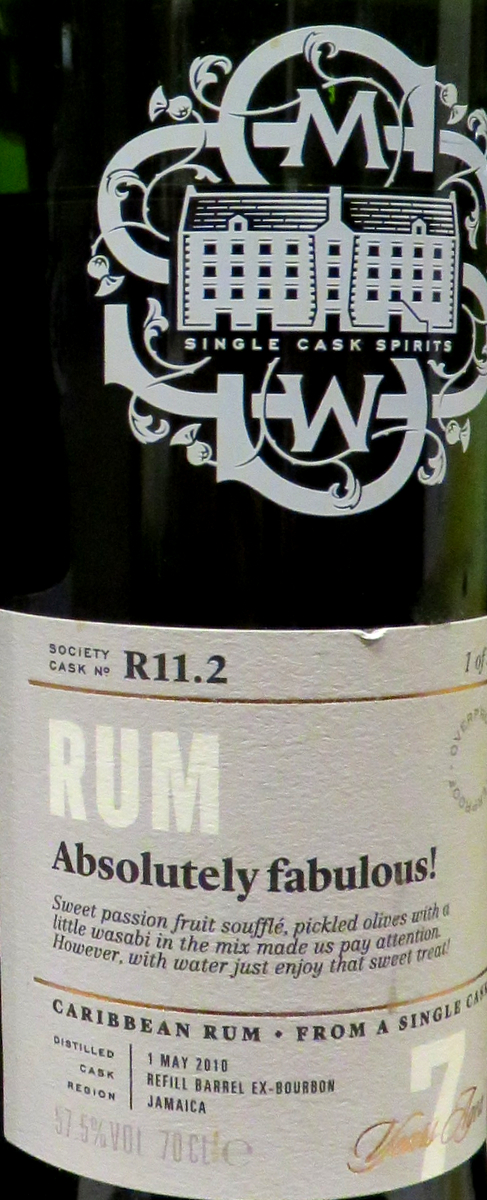

Anyone from my generation who grew up in the West Indies knows of the scalpel-sharp satirical play “Smile Orange,” written by that great Jamaican playwright, Trevor Rhone, and made into an equally funny film of the same name in 1976. It is quite literally one of the most hilarious theatre experiences of my life, though perhaps an islander might take more away from it than an expat. Why do I mention this irrelevancy? Because I was watching the YouTube video of the film that day in Berlin when I was sampling the Worthy Park series R 11.3, and though the film has not aged as well as the play, the conjoined experience brought to mind all the belly-jiggling reasons I so loved it, and Worthy Park’s rums.

Anyone from my generation who grew up in the West Indies knows of the scalpel-sharp satirical play “Smile Orange,” written by that great Jamaican playwright, Trevor Rhone, and made into an equally funny film of the same name in 1976. It is quite literally one of the most hilarious theatre experiences of my life, though perhaps an islander might take more away from it than an expat. Why do I mention this irrelevancy? Because I was watching the YouTube video of the film that day in Berlin when I was sampling the Worthy Park series R 11.3, and though the film has not aged as well as the play, the conjoined experience brought to mind all the belly-jiggling reasons I so loved it, and Worthy Park’s rums. The distillation run from 2010 must have been a good year for Worthy Park, because the SMWS bought no fewer than seven separate casks from then to flesh out its R11 series of rums (R11.1 through R11.6 were distilled May 1st of that year, with R11.7 in September, and all were released in 2017). After that, I guess the Society felt its job was done for a while and pulled in its horns, releasing nothing in 2018 from WP, and only one more — R11.8 — the following year; they called it “Big and Bountiful” though it’s unclear whether this refers to Jamaican feminine pulchritude or Jamaican rums.

The distillation run from 2010 must have been a good year for Worthy Park, because the SMWS bought no fewer than seven separate casks from then to flesh out its R11 series of rums (R11.1 through R11.6 were distilled May 1st of that year, with R11.7 in September, and all were released in 2017). After that, I guess the Society felt its job was done for a while and pulled in its horns, releasing nothing in 2018 from WP, and only one more — R11.8 — the following year; they called it “Big and Bountiful” though it’s unclear whether this refers to Jamaican feminine pulchritude or Jamaican rums. It sounds strange to say it, but the

It sounds strange to say it, but the

Anyway, this was a 12 year old, continentally-aged Guyanese rum (no still is mentioned, alas), of unknown outturn, aged 12 years in Laphroaig whisky casks and released at the 46% strength that was once a near standard for rums brought out by

Anyway, this was a 12 year old, continentally-aged Guyanese rum (no still is mentioned, alas), of unknown outturn, aged 12 years in Laphroaig whisky casks and released at the 46% strength that was once a near standard for rums brought out by

Palate – Even if they didn’t say so on the label, I’d say this is almost completely Guyanese just because of the way all the standard wooden-still tastes are so forcefully put on show – if there

Palate – Even if they didn’t say so on the label, I’d say this is almost completely Guyanese just because of the way all the standard wooden-still tastes are so forcefully put on show – if there

The French-bottled, Australian-distilled Beenleigh 5 Year Old Rum is a screamer of a rum, a rum that wasn’t just released in 2018, but unleashed. Like a mad roller coaster, it careneed madly up and down and from side to side, breaking every rule and always seeming just about to go off the rails of taste before managing to stay on course, providing, at end, an experience that was shattering — if not precisely outstanding.

The French-bottled, Australian-distilled Beenleigh 5 Year Old Rum is a screamer of a rum, a rum that wasn’t just released in 2018, but unleashed. Like a mad roller coaster, it careneed madly up and down and from side to side, breaking every rule and always seeming just about to go off the rails of taste before managing to stay on course, providing, at end, an experience that was shattering — if not precisely outstanding. I still remember how unusual the

I still remember how unusual the

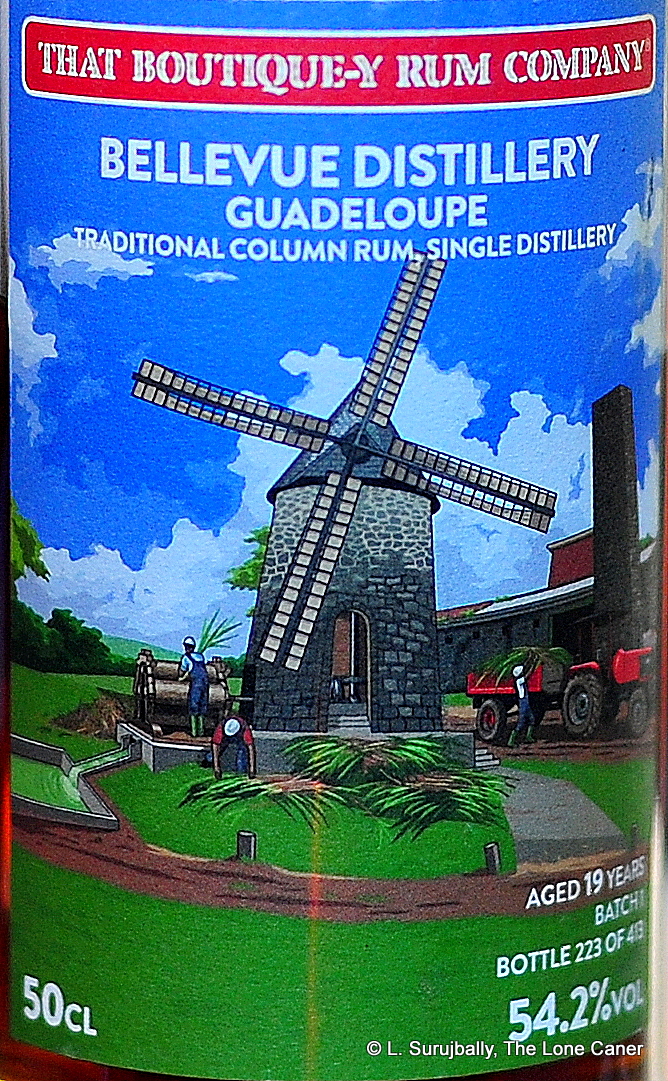

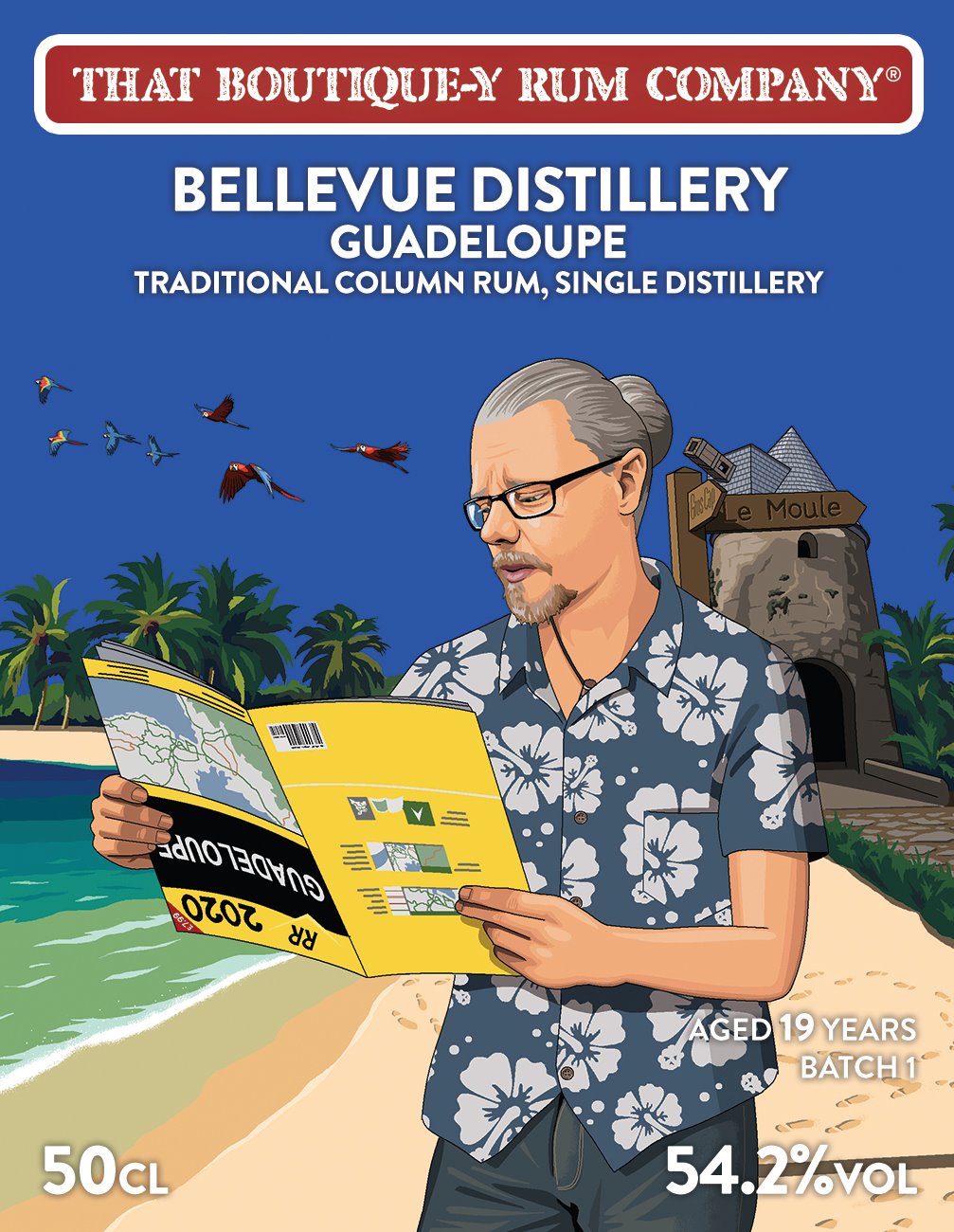

Take this one, which proves that TBRC has a knack for ferreting out good barrels. It’s not often you find a rum that is from the French West Indies aged beyond ten years — Neisson’s been making a splash recently with its 18 YO, you might recall, for that precise reason. To find one that’s a year older from Guadeloupe in the same year is quite a prize and I’ll just mention it’s 54.2%, aged seven years in Guadeloupe and a further twelve in the UK, and outturn is 413 bottles. On stats alone it’s the sort of thing that makes my glass twitch.

Take this one, which proves that TBRC has a knack for ferreting out good barrels. It’s not often you find a rum that is from the French West Indies aged beyond ten years — Neisson’s been making a splash recently with its 18 YO, you might recall, for that precise reason. To find one that’s a year older from Guadeloupe in the same year is quite a prize and I’ll just mention it’s 54.2%, aged seven years in Guadeloupe and a further twelve in the UK, and outturn is 413 bottles. On stats alone it’s the sort of thing that makes my glass twitch. Guadeloupe rums in general lack something of the fierce and stern AOC specificity that so distinguishes Martinique, but they’re close in quality in their own way, they’re always good, and frankly, there’s something about the relative voluptuousness of a Guadeloupe rhum that I’ve always liked. Peter sold me on the quality of the

Guadeloupe rums in general lack something of the fierce and stern AOC specificity that so distinguishes Martinique, but they’re close in quality in their own way, they’re always good, and frankly, there’s something about the relative voluptuousness of a Guadeloupe rhum that I’ve always liked. Peter sold me on the quality of the  Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688

Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688 Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

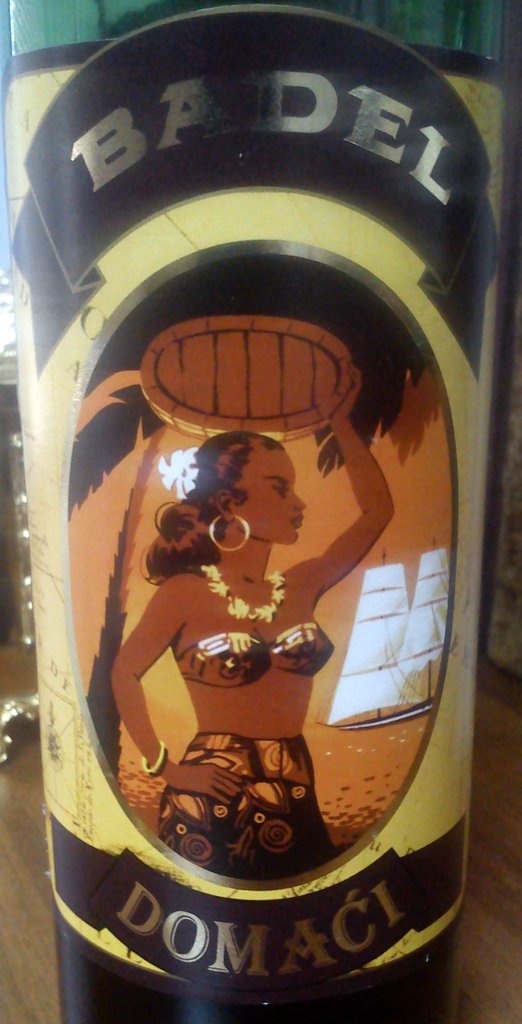

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

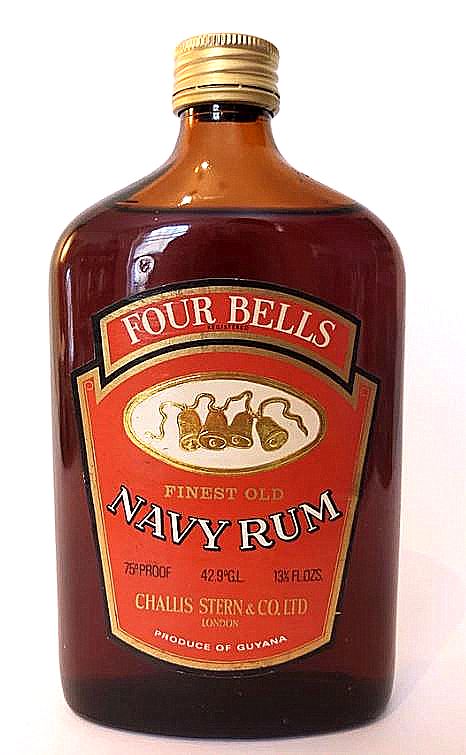

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

Whatever the case, the rum was as fierce as the Diamond, and even at a microscopically lower proof, it took no prisoners. It exploded right out of the glass with sharp, hot, violent aromas of tequila, rubber, salt, herbs and really good olive oil. If you blinked you could see it boiling. It swayed between sweet and salt, between soya, sugar water, squash, watermelon, papaya and the tartness of hard yellow mangoes, and to be honest, it felt like I was sniffing a bottle shaped mass of whup-ass (the sort of thing Guyanese call “regular”).

Whatever the case, the rum was as fierce as the Diamond, and even at a microscopically lower proof, it took no prisoners. It exploded right out of the glass with sharp, hot, violent aromas of tequila, rubber, salt, herbs and really good olive oil. If you blinked you could see it boiling. It swayed between sweet and salt, between soya, sugar water, squash, watermelon, papaya and the tartness of hard yellow mangoes, and to be honest, it felt like I was sniffing a bottle shaped mass of whup-ass (the sort of thing Guyanese call “regular”).

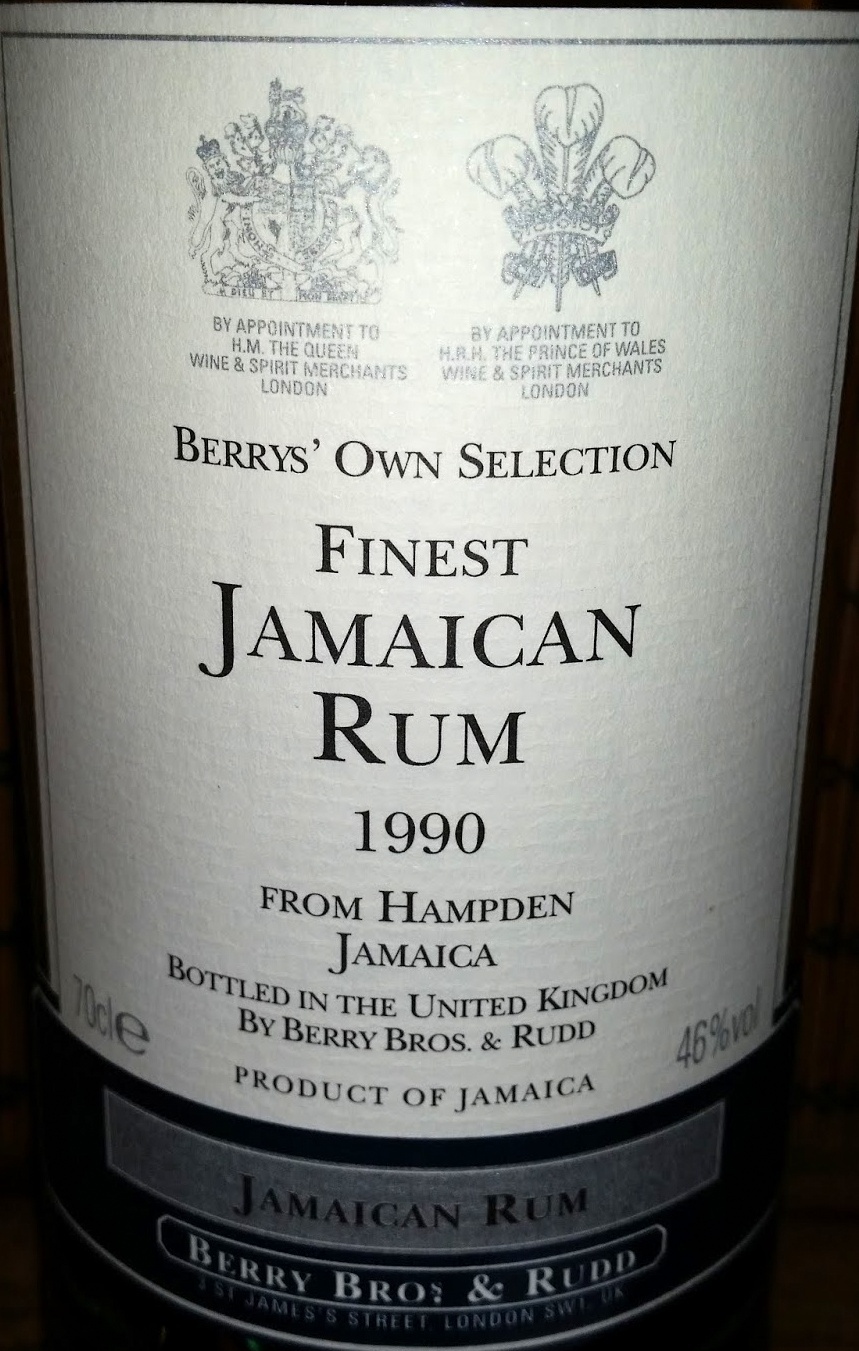

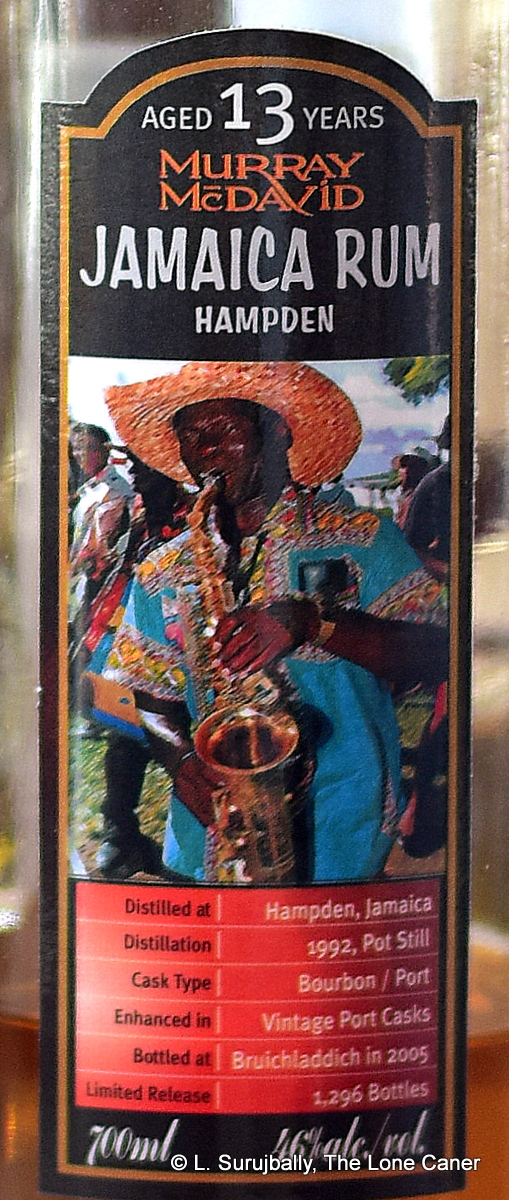

Tasting notes: definitely Jamaican, that hogo and funk was unmistakable, though it seemed more muted than the fierce cask strength Hampdens we’ve been seeing of late. It smelled initially of pencil shavings, crisp acetones, nail polish remover, a freshly painted room and glue. After opening up, I went back some minutes later and found softer aromas – red wine, molasses, honey, chocolate, and cream cheese and salted butter on fresh croissants, really yummy. And this is not to ignore the ever-present sense of fruitiness – dark grapes, black cherries, ripe mangoes, papayas, gooseberries and some bananas, just enough to round off the entire nose.

Tasting notes: definitely Jamaican, that hogo and funk was unmistakable, though it seemed more muted than the fierce cask strength Hampdens we’ve been seeing of late. It smelled initially of pencil shavings, crisp acetones, nail polish remover, a freshly painted room and glue. After opening up, I went back some minutes later and found softer aromas – red wine, molasses, honey, chocolate, and cream cheese and salted butter on fresh croissants, really yummy. And this is not to ignore the ever-present sense of fruitiness – dark grapes, black cherries, ripe mangoes, papayas, gooseberries and some bananas, just enough to round off the entire nose.