There are five bottlings planned for the Australian Distillery Kalki Moon’s “Cane Farmer” Series, named as an homage to the farmers in Queensland who were instrumental in developing the state. The Plant Cane — an unaged white spirit which is a rum in all but name — was the second, introduced in December 2020, with spiced and darker aged expressions that can be called “rum” locally being developed for future release.

We’ll go into the background of the company later, but for now, let’s just talk about this white unaged spirit, made from molasses (yes, molasses, not juice), fermented with a commercial yeast for six days and then run through a 600-liter pot still called “Pristilla”…twice. The high proof spirit coming off the still is then diluted with water over a period of around eight weeks, down to the 44% we get here.

Kalki Moon has several stills – a small, 100-liter pot still (for gin) made in Australia, and another 200-liter pot still (for rum) bought in China were the original stills. Other stills were added later: Pristilla (for more rum), then “Marie” — another Chinese 1000-liter still sourced in 2020 (for yet more gin) — and in 2022 a 3000-liter Australian-made pot still will replace Pristilla (for even more rum).

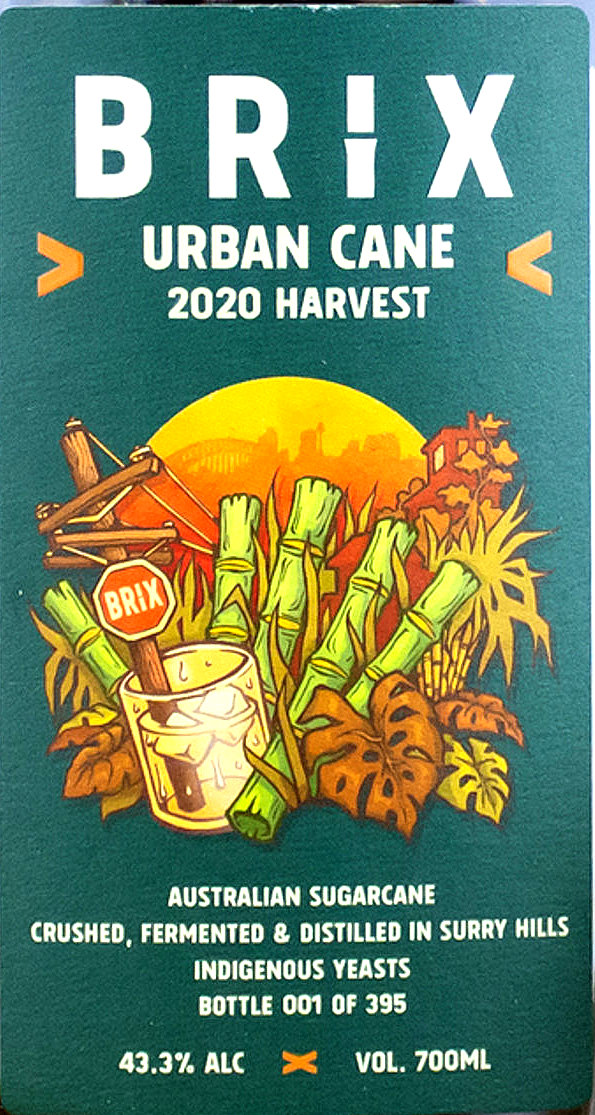

This white rum (I’ll call it that and ask for Australians’ indulgence in the matter) has certain similarities to both the Brix and the JimmyRum whites we’ve already looked at, but with its own twist. The rum has and interesting character…and the nose, it must be said, is really kind of all over the place. It starts out smelling of brine, olives and iodine, and even puts out a vague scent of pine-sol disinfectant, before remembering it’s supposed to be a rum and choking that off. Then you get a sort of dhal or lentil soup with black pepper and masala spice, which in turn morphs into a more conventional Jamaican low-rent funkiness of banana skins, overripe fleshy stoned fruits and soft pineapples, and the hogo of meat beginning to go. When you’re done you feel like you’ve just been mugged by a happily unwashed baby fresh off his daily vegemite.

Never fear, though, most of all this confusion is gone by the time it’s time to start sipping the thing. Here we get a solid, sweet, luscious depth: strawberries, pineapples, very dark and very ripe cherries, melons, papayas and squash (yes, squash). Some squishy overripe Thai mangoes and maybe some guavas, with just enough citrus being hinted at to not make it a cloying mess, and just enough salt to balance all that off. It’s not entirely a success, but not something you would forget in a hurry either. The finish goes off in its own direction again, evidently forgetting (again) what it was supposed to be, and leaves me with a simultaneously dry and watery sort of cane-vinegar-wine vibe, cardboard, and a bland fruit salad where nothing can be picked out.

It’s an odd rum, and to be honest I really kinda like it, because for one, it really does taste like a rum, and two, even if the tastes and smells don’t always play nice and go helter skelter all over the place, there’s no denying that by some alchemy of Mr. Prosser’s skill, it all holds together and provides a punch of white rum flavour one can’t dismiss out of hand. Not everything can be “like from the Caribbean” and not everything should be. With Kalki Moon’s first batch, my advice for most would be to mix this thing into a daiquiri or a mojito or something, and check it out that way…it’s really going to make those old stalwarts jump. For those of strength, fortitude, and Caner-style mad courage, drink it neat. You won’t forget it in a hurry, I’m thinking…just before you start wondering what a full proof version would be like.

(#883)(82/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Company Background

Kalki Moon is named after an enduring image in the mind of the founder Rick Prosser, that of the full moon over the fields of Bundaberg in the neighbourhood of Kalkie, where he had built his house. After working for thirteen years and becoming a master distiller at the Bundaberg Distillery and dabbling in some consultancy work, Mr. Prosser decided to give it a shot for himself, and enlisted friends and family to help financially and operationally support his endeavours to build and run his own artisanal distillery, which opened in 2017 with two small stills.

Australian law requires any spirit labelled “rum” to have been aged for two years, which places a burden on new startup distilleries wanting to produce it there…they have to make cash flow to survive for at least that long while their stock matures. That need to make sales from the get-go pushed the tiny distillery into the vodka- and gin-making business (gin was actually a last minute decision) — Mr. Prosser felt that the big brands produced by his previous employer, Diageo, had their place, but there were opportunities for craft work too.

Somewhat to his surprise, the gins he made – a classic, a premium, a navy strength and even a pink – sold well enough that he became renowned for those, even while adding yet other spirits to his company’s portfolio. Still, he maintains that it was always rum for which he was aiming, and gin just paid the bills, and in 2020 he commissioned a third, larger still (named “Marie”, after his grandmother) to allow him to expand production even further. Other cash generating activities came from the spirits-trail distillery tourists who came on the tours afforded by having several brewing and distilling operations in a very concentrated area of Bundaberg – so there are site visits, tasting sessions and so on.

At the same time, he has been experimenting with rums – some, of course, ended up becoming the Plant Cane – but it took time to get the cuts and fermentation and still settings right, so that a proper rum could be set to age. At this point I believe the spiced and maybe the dark (aged) rums will be ready for release in 2022 or shortly thereafter. The gins are too well-made, too profitable and too widely appreciated, now, to be abandoned, so I imagine that Kalki will continue to be very much a multi-product company. It remains to be seen whether the dilution of focus I’ve remarked on before with respect to small American distilleries who multi-task the hell out of their stills, will hamper making a truly great artisanal rum, or whether all these various products will get their due moment in the sun. Personally I think that if his gins can be good enough to win awards right out of the gate, it sure will be interesting to watch what Mr. Prosser does when he gets a head of steam under him, and the aged rums start coming out the door. So far, even the unaged rum he made is well worth a taste.

Other Notes

- As with all the Australian rums reviewed as part of the 2021 Aussie Advent Calendar, a very special shout out and touch of the Panama to Mr. And Mrs. Rum, who sent me a complete set free of charge when they heard of my interest (it was not for sale outside Australia). Thanks again to you both.

- A sample pic shows what I tasted from but it really lacks a visual something. When I scoured around for bottle pics, I found the two (much better) photographs which you see included above, so many thanks to Justin Galloway and (chaste) kisses to the Two Rum Chicks, who kindly allowed me to use their work.

Depaz’s 45% rhum blanc agricole is not one of these uber-exclusive, limited-edition craft whites that uber-dorks are frothing over. But the quality and taste of even this standard white shows exactly how good the

Depaz’s 45% rhum blanc agricole is not one of these uber-exclusive, limited-edition craft whites that uber-dorks are frothing over. But the quality and taste of even this standard white shows exactly how good the

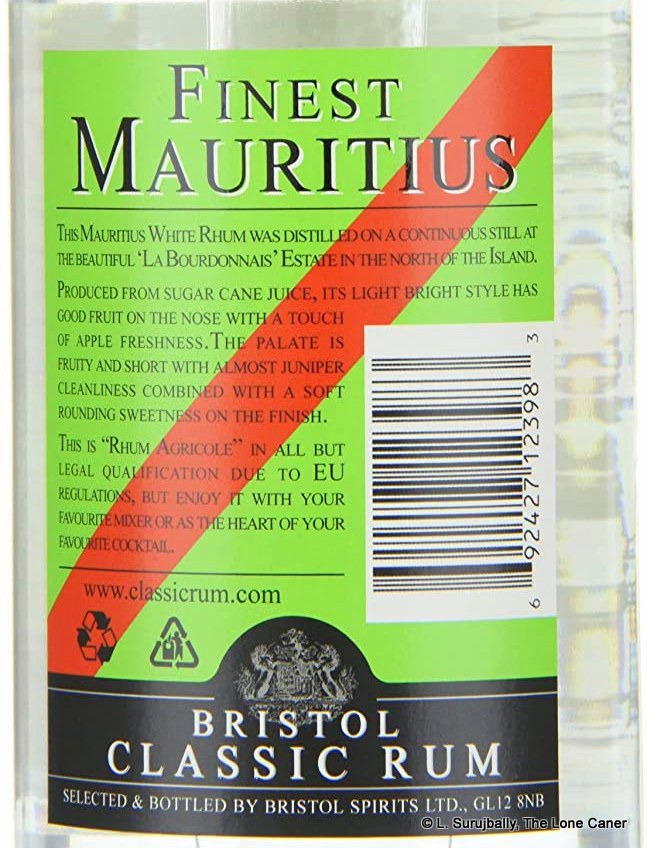

La Rhumerie de Chamarel, that Mauritius outfit we last saw when I reviewed their 44% pot-still white, doesn’t sit on its laurels with a self satisfied smirk and think it has achieved something. Not at all. In point of fact it has a couple more whites, both cane juice derived and distilled on their

La Rhumerie de Chamarel, that Mauritius outfit we last saw when I reviewed their 44% pot-still white, doesn’t sit on its laurels with a self satisfied smirk and think it has achieved something. Not at all. In point of fact it has a couple more whites, both cane juice derived and distilled on their

Personally I have a thing for pot still hooch – they tend to have more oomph, more get-up-and-go, more pizzazz, better tastes. There’s more character in them, and they cheerfully exude a kind of muscular, addled taste-set that is usually entertaining and often off the scale. The Jamaicans and Guyanese have shown what can be done when you take that to the extreme. But on the other side of the world there’s this little number coming off a small column, and I have to say, I liked it even more than its pot still sibling, which may be the extra proof or the still itself, who knows.

Personally I have a thing for pot still hooch – they tend to have more oomph, more get-up-and-go, more pizzazz, better tastes. There’s more character in them, and they cheerfully exude a kind of muscular, addled taste-set that is usually entertaining and often off the scale. The Jamaicans and Guyanese have shown what can be done when you take that to the extreme. But on the other side of the world there’s this little number coming off a small column, and I have to say, I liked it even more than its pot still sibling, which may be the extra proof or the still itself, who knows.

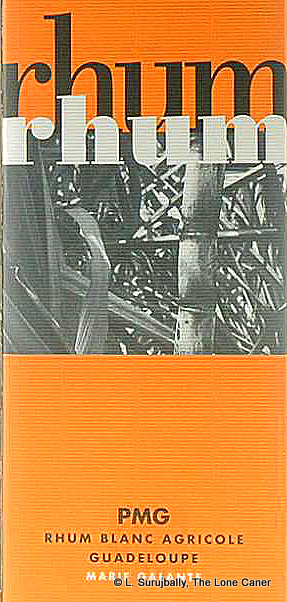

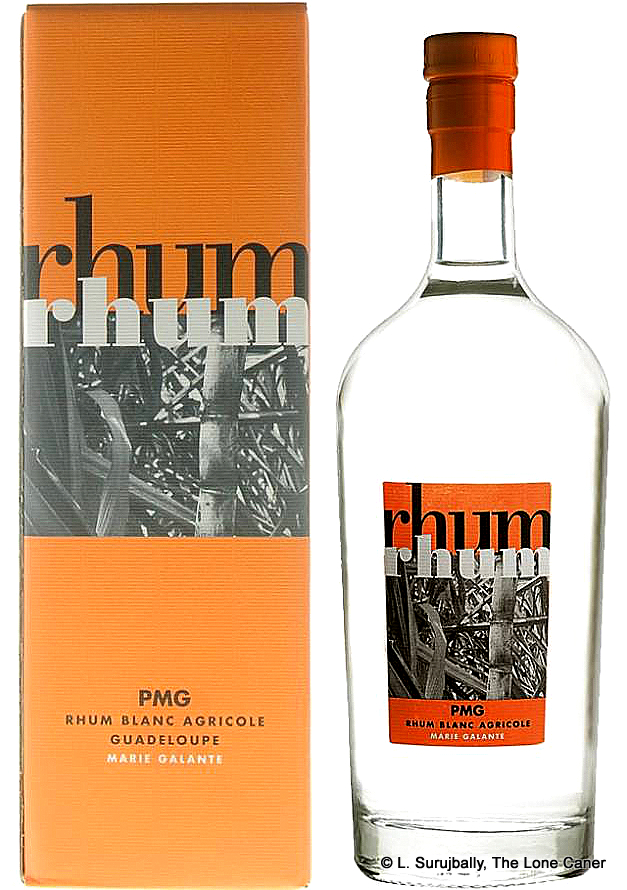

Although the plan was always to sell white (unaged) rhum, some was also laid away to age and the aged portion turned into the “Liberation” series in later years. The white was a constant, however, and remains on sale to this day – this orange-labelled edition was 56% ABV and I believe it is always released together with a green-labelled version at 41% ABV for gentler souls. It doesn’t seem to have been marked off by year in any way, and as far as I am aware production methodology remains consistent year in and year out.

Although the plan was always to sell white (unaged) rhum, some was also laid away to age and the aged portion turned into the “Liberation” series in later years. The white was a constant, however, and remains on sale to this day – this orange-labelled edition was 56% ABV and I believe it is always released together with a green-labelled version at 41% ABV for gentler souls. It doesn’t seem to have been marked off by year in any way, and as far as I am aware production methodology remains consistent year in and year out. From the description I’m giving, it’s clear that I like this rhum, a lot. I think it mixes up the raw animal ferocity of a more primitive cane juice rhum with the crisp and clear precision of a Martinique blanc, while just barely holding the damn thing on a leash, and yeah, I enjoyed it immensely. I do however, wonder about its accessibility and acceptance given the price, which is around $90 in the US. It varies around the world and on Rum Auctioneer it averaged out around £70 (crazy, since

From the description I’m giving, it’s clear that I like this rhum, a lot. I think it mixes up the raw animal ferocity of a more primitive cane juice rhum with the crisp and clear precision of a Martinique blanc, while just barely holding the damn thing on a leash, and yeah, I enjoyed it immensely. I do however, wonder about its accessibility and acceptance given the price, which is around $90 in the US. It varies around the world and on Rum Auctioneer it averaged out around £70 (crazy, since  In an ever more competitive market – and that includes French island agricoles – every chance is used to create a niche that can be exploited with first-mover advantages. Some of the agricole makers, I’ve been told, chafe under the strict limitations of the AOC which they privately complain limits their innovation, but I chose to doubt this: not only there some amazing rhums coming out the French West Indies within the appellation, but they are completely free to move outside it (as

In an ever more competitive market – and that includes French island agricoles – every chance is used to create a niche that can be exploited with first-mover advantages. Some of the agricole makers, I’ve been told, chafe under the strict limitations of the AOC which they privately complain limits their innovation, but I chose to doubt this: not only there some amazing rhums coming out the French West Indies within the appellation, but they are completely free to move outside it (as

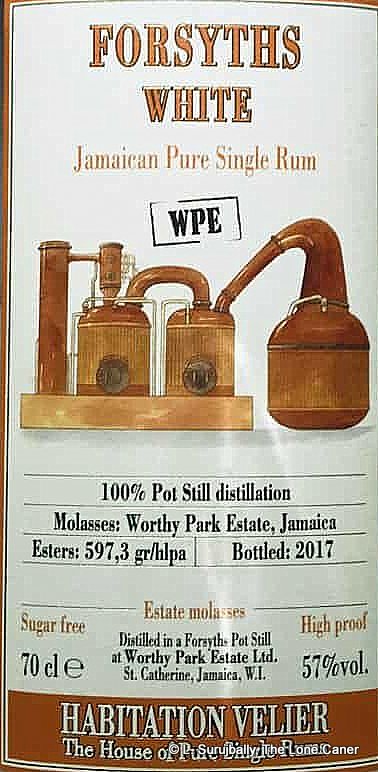

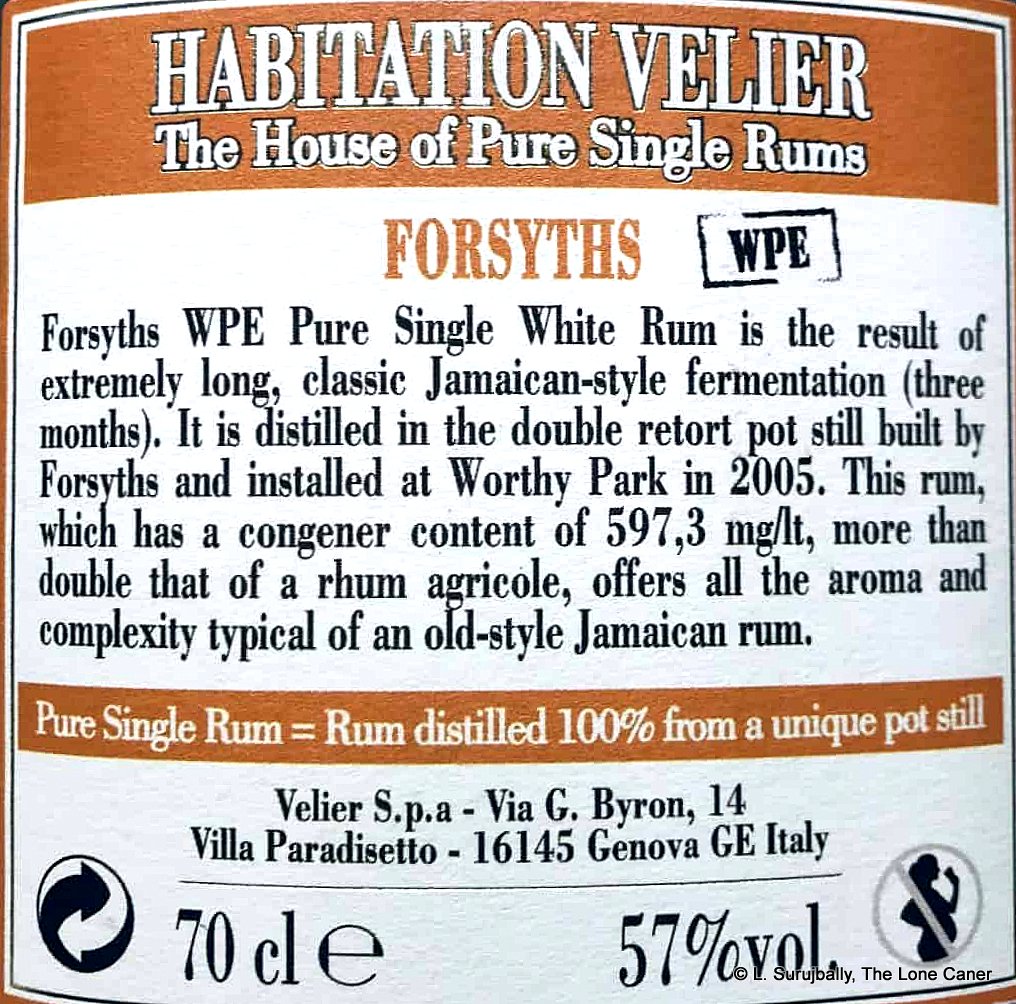

Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with

Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with  The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember

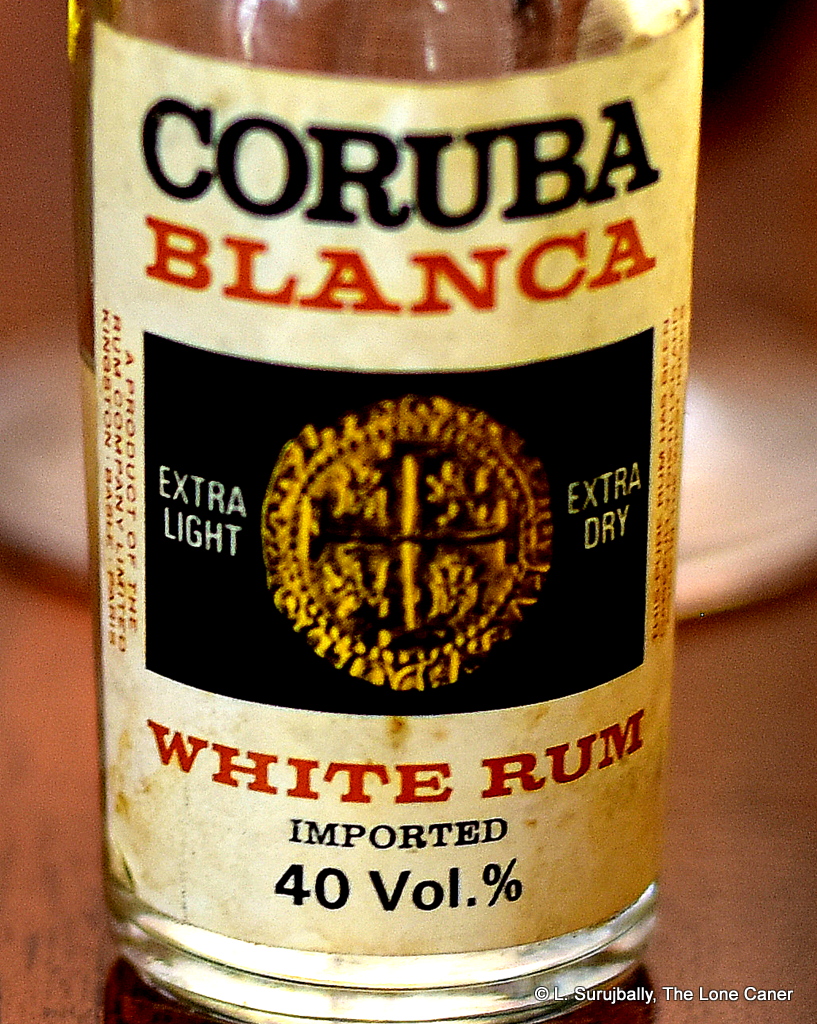

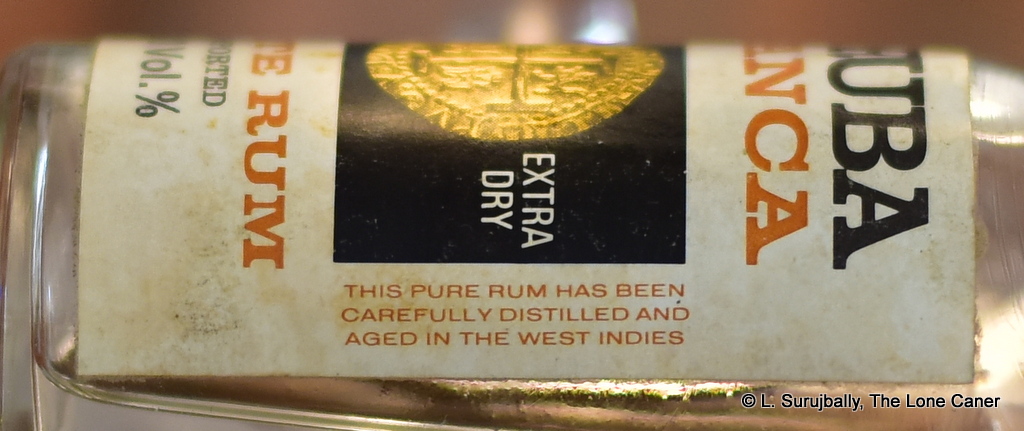

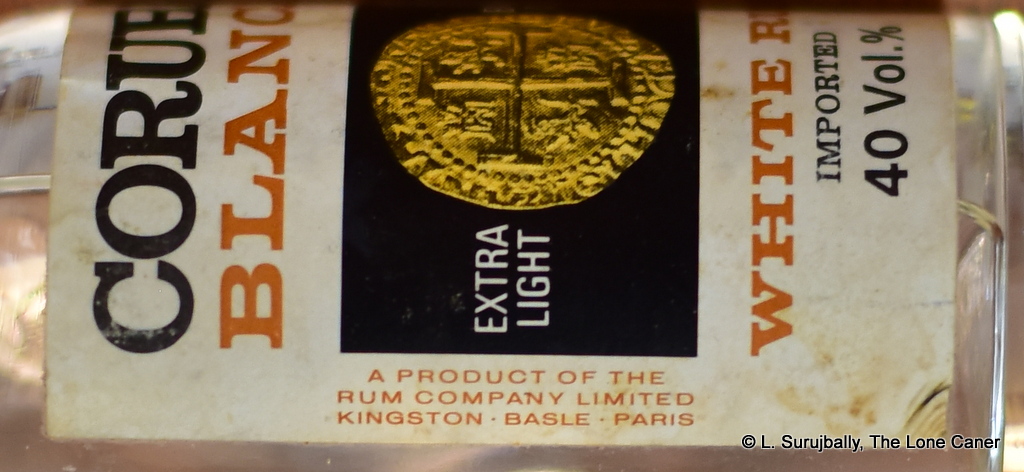

The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember  Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

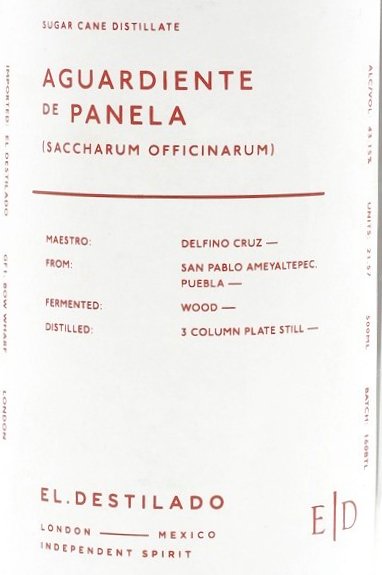

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.