Not a bah-humbug rum…more like something of a “meh”.

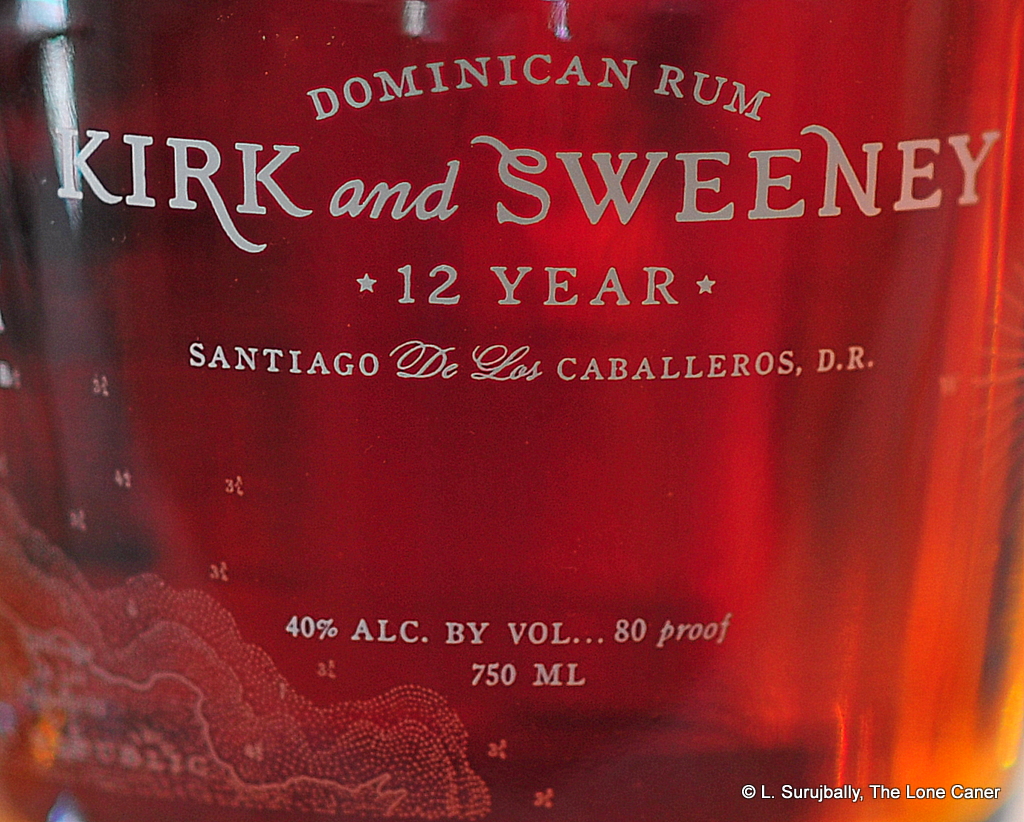

I have an opinion on larger issues raised by this rum and others like it, but for the moment let’s just concentrate on the review before further bloviating occurs. Kirk and Sweeney is a Dominican Republic originating rum distilled and aged in the DR by Bermudez (one of the three Big Bs of Barcelo, Bermudez and Brugal) before being shipped off to California for bottling by 35 Maple Street, the spirits division of The Other Guy (a wine company). And what a bottle it is – an onion bulb design, short and chubby and very distinctive, with the batch and bottle number on the label. That alone makes it stand out on any shelf dominated by the standard bottle shapes. It is named after a Prohibition-era schooner which was captured by the Coast Guard in 1924 and subsequently turned into a training vessel (and renamed), which is just another marketing plug meant to anchor the rum to its supposed piratical and disreputable antecedents.

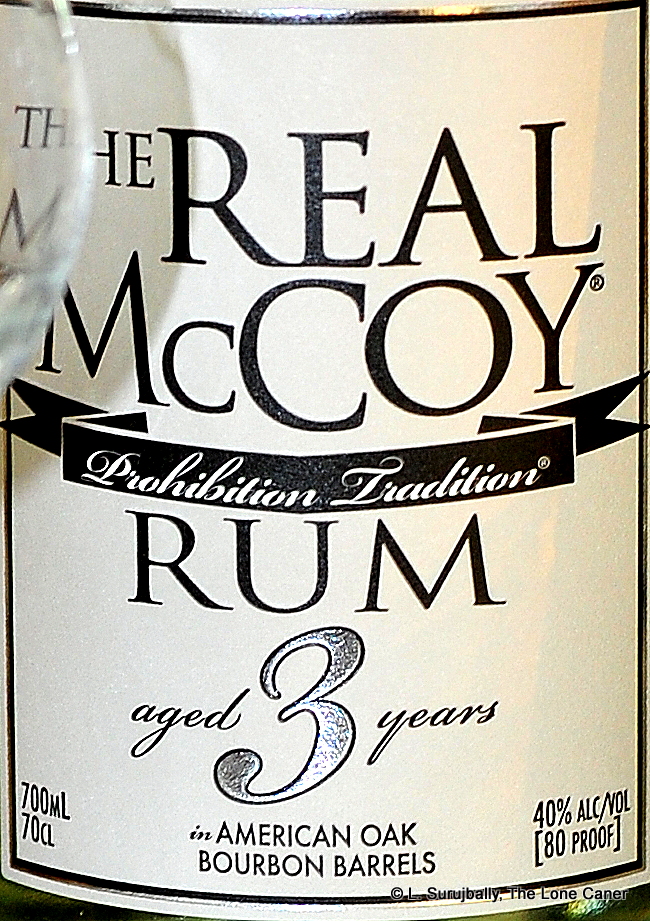

Dark orange in colour, bottled at 40%, the K&S is aged for 12 years in the usual American oak casks. Where all that ageing went is unclear to me, because frankly, it didn’t have a nose worth a damn. Oak? What oak? Smelling it revealed more light vanilla and butterscotch than anything else, with attendant toffee and ice cream. It was gentle to a fault, and so uncomplex as to be just about boring…there was nothing new here at all. “Dull” one commentator remarked. Even the Barcelo Imperial exhibited more courage, wussy as it was.

To taste it was marginally better, if similarly unadventurous. Medium bodied, with an unaggressive profile, anchored by a backbone of vanilla and honey. There was a bit of the oak tannins here, fiercely controlled as to be almost absent; not much else of real complexity. Some floral notes, cinnamon, plums and richer fruits could be discerned, but they were never allowed to develop properly, or given their moment in the sun – the primary vanilla and butterscotch was simply too dominating (and for a rum that was as easy going as this one, that’s saying a lot). The Brugal 1888 exhibited a similar structure, but balanced things off a whole lot better. Maybe it was just me – I simply didn’t see where all the ageing went, and there was little satisfaction at the back end which was short, soft as a feather pillow, and primarily (you guessed it) toffee and cocoa and more vanilla.

To taste it was marginally better, if similarly unadventurous. Medium bodied, with an unaggressive profile, anchored by a backbone of vanilla and honey. There was a bit of the oak tannins here, fiercely controlled as to be almost absent; not much else of real complexity. Some floral notes, cinnamon, plums and richer fruits could be discerned, but they were never allowed to develop properly, or given their moment in the sun – the primary vanilla and butterscotch was simply too dominating (and for a rum that was as easy going as this one, that’s saying a lot). The Brugal 1888 exhibited a similar structure, but balanced things off a whole lot better. Maybe it was just me – I simply didn’t see where all the ageing went, and there was little satisfaction at the back end which was short, soft as a feather pillow, and primarily (you guessed it) toffee and cocoa and more vanilla.

So the rum lacks the power and jazz and ever-evolving taste profile that I mark more highly, and overall it’s just not my speed. Note, however, that residents in the DR prefer lighter, softer rums (which can be bottled at 37.5%) and its therefore not beyond the pale for K&S rum to reflect their preference since (according to one respected correspondent of mine) the objective here is to make an authentic, genuine DR rum. And that, it is argued, they have achieved, and I have to admit – whatever my opinion of it is, it’s also a very affordable, very drinkable rum that many will appreciate because of that same laid back, chill-out nature to which I’m so indifferent. Just because it doesn’t work for me doesn’t mean a lot of people aren’t going to like it. Not everyone has to like full proof rums, and not everyone will ever be able to afford indie outturns of a few hundred bottles, if they can even get them; and frankly not everyone wants a vibrating seacan of oomph landing on their palate. For such people, then, this rum is just peachy. For me, it just isn’t, perhaps because I’m not looking for rums that try to please everyone, are too easy and light, and don’t provide any challenge or true points of interest.

Opinion:

Years of drinking rums from across the spectrum leads me to believe that there’s something more than merely cultural that stratifies the various vocal tribes of rummies. It is a divide between rum Mixers and rum Drinkers, between bourbon fanciers moving into rums versus hebridean maltsters doing the same (with new rum evangelists jumping on top of both), all mixed up with a disagreement among three additional groups: lovers of those rums made by micro-distillers in the New World, aficionados of country-wide major brands, and fans of the independent “craft” bottlers. Add to that the fact that people not unnaturally drink only what they can find in their local likker establishment, and what that translates into is a different ethos of what each defines as a quality rum, and is also evident in the different strengths that each regards as standard, and so the concomitant rums they seemingly prefer.

That, in my opinion goes a far way to explaining why a rum like the K&S is praised by many in the New World fora as a superb rum…while some of the Old World boyos who are much more into cask strength monsters made by independent bottlers, smile, shrug and move on, idly wondering what the fuss is all about. Because on one level the K&S is a perfectly acceptable rum, while on another it really isn’t…which side of the divide you’re on will likely dictate what your opinion of it and others like it, is.

(#280 | 81/100)

Other notes

- I actually think it’s closer to a solera in taste profile – the Opthimus 18 was what I thought about – but most online literature says it is really aged for twelve years. I chose to doubt that.

- Bottle purchased in 2013…I dug it out of storage while on a holiday back in Canada in 2016 for this review, and then again in 2024 when I recorded a video recap.

- K&S also produces an 18 and 23 year old version. The rum was noted to be a blend, and from molasses, in a 2020 Forbes article, where it was also noted that the age statement was dropped from current labels.