By today’s standards, Brugal, home of the very good 1888 Gran Reserva, made something of a fail in the genus of white rums with this Blanco. That’s as much a function of its tremblingly weak-kneed proof point (37.5%, teetering on the edge of not being a rum at all) as its filtration which makes it bland to the point of vanilla white (oh, wait….). Contrast it with the stern, uncompromising blanc beefcakes of the French islands and independents which blow the roof off in comparison: they excite amazed and disbelieving curses — this promotes indifferent yawns.

To some extent remarks like that are unfair to those who dial into precisely the coordinates the Blanco provides — a light and easy low-end Cuban style barroom mixer without aggro or bombast, which can just as easily be had in a sleepy backroad rumshop someplace without fearing for one’s health or sanity after the fact. But they also encapsulate how much the world of white rums has progressed since people woke up to the ripsnorting take-no-prisoners braggadocio of modern blancs, whites, clairins, grogues and unaged pot still rhinos that litter the bar area with the expired glottises of unwary rum reviewers.

Technical details are actually rather limited: it’s a rum aged for two years in American oak, then triple filtered, and nothing I’ve read suggests anything but a column still distillate. This results in a very light, almost wispy profile which is very difficult to come to grips with.

Take the nose – it was so very faint. Being aware of the proof point, I took my time with it and teased out notes of Sprite, Fanta, sugar water, and watermelon juice, mixed up with the faintest suggestion of brine. Further sphincter-clenching concentration brought out hints of vanilla and light coconut shavings, lemon infused soda water, and that was about all, which, it must be conceded, didn’t entirely surprise me.

All this continued on to the tasting. It was hardly a maelstrom of hot and violent complexity, of course, presenting very gently and smoothly, almost with anorexic zen-level calm. It was thin, light and lemony, and teased with a bit of wax, the creaminess of salty butter, coconut shavings, apples and cumin — but overall the Blanco makes no statement for its own quality because it has so little of anything. Basically, it’s all gone before you can come to grips with it. Finish? Obviously the makers didn’t think we needed one, and followed through on that assumption by not providing any.

The question I alwys ask with rums like the underproofed Blanco is, who is it made for? – because that might give me some idea of why it was made the way it was. I mean, the Brugal 151 was supposed to be for cocktails and the premium aged anejos were for sipping, so where does that leave something as milquetoast as this? Me, if I was hanging around with friends in a hot tropical island backstreet, banging the dominos down with a bowl of ice, cheap plastic tumblers and this thing, I would probably enjoy having it on the rocks. On the other hand, if I was with a bunch of my fellow rum chums, showing and sharing my stash, I’d hide it out of sheer embarrassment. Because compared with the white rums which impress me so much more, this isn’t much of anything.

(#608)(68/100)

Other notes

Company background: Not to be confused with Dominica, the Dominican Republic is the Spanish speaking eastern half of the island of Hispaniola…the western half is Haiti. Three distilleries known as the Three Bs operate in the DR: Bermudez in the Santiago area, the Santo Domingo distillery called Barcelo, and Brugal in the north coast. Brugal, founded in 1888, seems to be the largest, perhaps as a result of being acquired in 2008 by the UK Edrington Group (they are the makers of Cutty Sark, and also own McCallan and Highland Park brands), and perhaps because Bermudez succumbed to internecine family squabbling, while Barcelo made some ill-advised forays into the hospitality sector and so both diluted their focus, to Brugal’s advantage.

There are other blancos made by Brugal: the Ron Blanco Especial, Blanco Especial Extra Dry, the 151 overproof, and the Blanco Supremo. Only the Supremo is listed on their website (accessed March 2019) and seems to be available online, which implies that all others are discontinued. That said, the production notes are similar for all of them, especially the 2 year minimum ageing and triple distillation.

Rumaniacs Review #091 | 0598

Rumaniacs Review #091 | 0598

Technical details are murky. All right, they’re practically non-existent. I think it’s a filtered column still rum, diluted down to standard strength, but lack definitive proof – that’s just my experience and taste buds talking, so if you know better, drop a line. No notes on ageing – however, in spite of one reference I dug up which noted it as unaged, I think it probably was, just a bit.

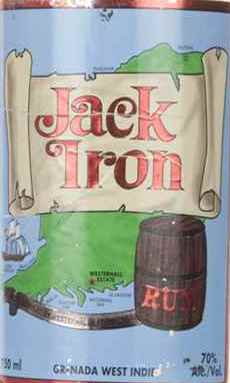

Technical details are murky. All right, they’re practically non-existent. I think it’s a filtered column still rum, diluted down to standard strength, but lack definitive proof – that’s just my experience and taste buds talking, so if you know better, drop a line. No notes on ageing – however, in spite of one reference I dug up which noted it as unaged, I think it probably was, just a bit. The Jack Iron rum from Westerhall is a booming overproof issued both in a slightly aged and a white version, and both are a whopping 70% ABV. While you can get it abroad — this bottle was tried in Italy, for example — my take is that it’s primarily a rum for local consumption (though which island can lay claim to it is a matter of idle conjecture), issued to paralyze brave-but-foolhardy tourists who want to show off their Chewbacca chests by drinking it neat, or to comfort the locals who don’t have time to waste getting hammered and just want to do it quick time. Add to that the West Indian slang for manly parts occasionally being iron and you can sense a sort of cheerful and salty islander sense of humour at work (see “other notes” below for an alternative backstory).

The Jack Iron rum from Westerhall is a booming overproof issued both in a slightly aged and a white version, and both are a whopping 70% ABV. While you can get it abroad — this bottle was tried in Italy, for example — my take is that it’s primarily a rum for local consumption (though which island can lay claim to it is a matter of idle conjecture), issued to paralyze brave-but-foolhardy tourists who want to show off their Chewbacca chests by drinking it neat, or to comfort the locals who don’t have time to waste getting hammered and just want to do it quick time. Add to that the West Indian slang for manly parts occasionally being iron and you can sense a sort of cheerful and salty islander sense of humour at work (see “other notes” below for an alternative backstory).

Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

Thailand doesn’t loom very large in the eyes of the mostly west-facing rum writers’ brigade, but just because they make it for the Asian palate and not the Euro-American cask-loving rum chums, doesn’t mean what they make can be ignored; similar in some respects to the light rums from Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Panama and Latin America, they may not be rums

Thailand doesn’t loom very large in the eyes of the mostly west-facing rum writers’ brigade, but just because they make it for the Asian palate and not the Euro-American cask-loving rum chums, doesn’t mean what they make can be ignored; similar in some respects to the light rums from Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Panama and Latin America, they may not be rums

And that creates a rum of uncommon docility. In fact, it’s close to being the cheshire cat of rums, so vaguely does it present itself. The soft silky nose was a watery insignificant blend of faint nothingness. Sugar water – faint; cucumbers – faint; cane juice – faint; citrus zest – faint (in fact here I suspect the lemon was merely waved rather gravely over the barrels before being thrown away); some cumin, and it’s possible that some molasses zipped past my nose, too fast to be appreciated.

And that creates a rum of uncommon docility. In fact, it’s close to being the cheshire cat of rums, so vaguely does it present itself. The soft silky nose was a watery insignificant blend of faint nothingness. Sugar water – faint; cucumbers – faint; cane juice – faint; citrus zest – faint (in fact here I suspect the lemon was merely waved rather gravely over the barrels before being thrown away); some cumin, and it’s possible that some molasses zipped past my nose, too fast to be appreciated.

Anyway, here’s what it was like. The nose of the Ilha da Madeira fell somewhere in the middle of the line separating a bored “meh” from a more disbelieving “holy-crap!”. It was a light melange of a playful sprite-like aroma mixed in with more serious brine and olives, a little sweet, and delicate – flowers, sugar water, grass, pears, guavas, mint, some marzipan. You could sense something darker underneath – cigarette tar, acetones – but these never came forward, and were content to be hinted at, not driven home with a sledge. Not really a brother to that fierce Jamaican brawler, more like a cousin, a closer relative to the

Anyway, here’s what it was like. The nose of the Ilha da Madeira fell somewhere in the middle of the line separating a bored “meh” from a more disbelieving “holy-crap!”. It was a light melange of a playful sprite-like aroma mixed in with more serious brine and olives, a little sweet, and delicate – flowers, sugar water, grass, pears, guavas, mint, some marzipan. You could sense something darker underneath – cigarette tar, acetones – but these never came forward, and were content to be hinted at, not driven home with a sledge. Not really a brother to that fierce Jamaican brawler, more like a cousin, a closer relative to the  In the last decade, several major divides have fissured the rum world in ways that would have seemed inconceivable in the early 2000s: these were and are cask strength (or full-proof) versus “standard proof” (40-43%); pure rums that are unadded-to versus those that have additives or are spiced up; tropical ageing against continental; blended rums versus single barrel expressions – and for the purpose of this review, the development and emergence of unmessed-with, unfiltered, unaged white rums, which in the French West Indies are called

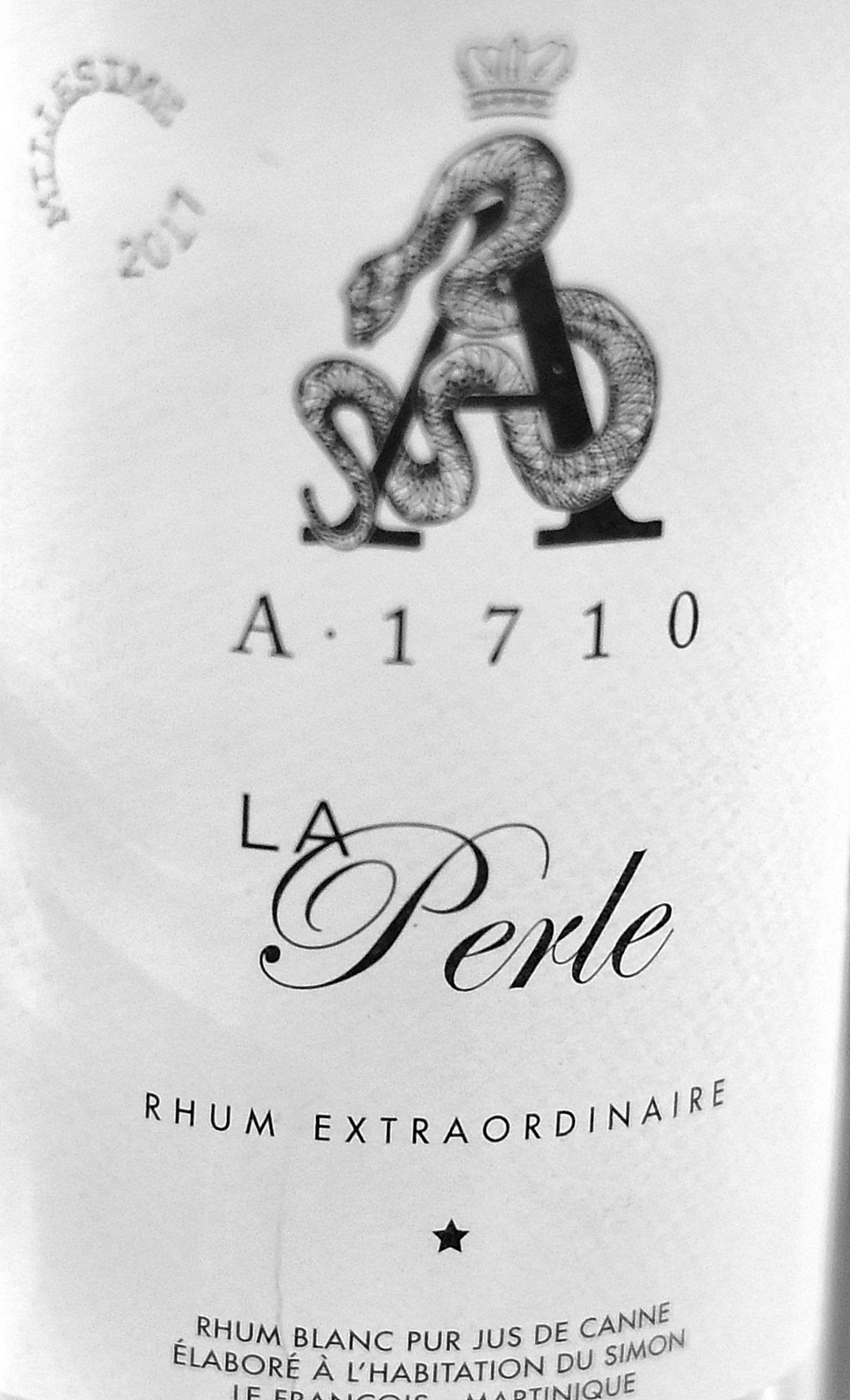

In the last decade, several major divides have fissured the rum world in ways that would have seemed inconceivable in the early 2000s: these were and are cask strength (or full-proof) versus “standard proof” (40-43%); pure rums that are unadded-to versus those that have additives or are spiced up; tropical ageing against continental; blended rums versus single barrel expressions – and for the purpose of this review, the development and emergence of unmessed-with, unfiltered, unaged white rums, which in the French West Indies are called

Well, that out of the way, let me walk you through the profile. Nose first: what was immediately evident is that it adhered to all the markers of a crisp agricole. It gave off of light grassy notes, apples gone off the slightest bit, watermelon, very light citrus and flowers. Then it sat back for some minutes, before surging forward with more: olives in brine, watermelon juice, sugar cane sap, peaches, tobacco and a sly hint of herbs like dill and cardamom.

Well, that out of the way, let me walk you through the profile. Nose first: what was immediately evident is that it adhered to all the markers of a crisp agricole. It gave off of light grassy notes, apples gone off the slightest bit, watermelon, very light citrus and flowers. Then it sat back for some minutes, before surging forward with more: olives in brine, watermelon juice, sugar cane sap, peaches, tobacco and a sly hint of herbs like dill and cardamom.

Unaged rums take some getting used to because they are raw from the barrel and therefore the rounding out and mellowing of the profile which ageing imparts, is not a factor. That means all the jagged edges, dirt, warts and everything, remain. Here that was evident after a single sip: it was sharp and fierce, with the licorice notes subsumed into dirtier flavours of salt beef, brine, olives and garlic pork (seriously!). It took some time for other aspects to come forward – gherkins, leather, flowers and varnish – and even then it was not until another half hour had elapsed that crisper acidic notes like unripe apples and thai lime leaves (I get those to buy in the local market), were noticeable. Plus some vanilla – where on earth did that come from? It all led to a long, duty, dry finish that provided yet more: sweet, sugary, sweet-and-salt soy sauce in a clear soup. Damn but this was a heady, complex piece of work. I liked it a lot, really.

Unaged rums take some getting used to because they are raw from the barrel and therefore the rounding out and mellowing of the profile which ageing imparts, is not a factor. That means all the jagged edges, dirt, warts and everything, remain. Here that was evident after a single sip: it was sharp and fierce, with the licorice notes subsumed into dirtier flavours of salt beef, brine, olives and garlic pork (seriously!). It took some time for other aspects to come forward – gherkins, leather, flowers and varnish – and even then it was not until another half hour had elapsed that crisper acidic notes like unripe apples and thai lime leaves (I get those to buy in the local market), were noticeable. Plus some vanilla – where on earth did that come from? It all led to a long, duty, dry finish that provided yet more: sweet, sugary, sweet-and-salt soy sauce in a clear soup. Damn but this was a heady, complex piece of work. I liked it a lot, really.