The “M&G” in the rhum’s title is not, as you might expect, the initials of the two founders of this small operation in Cabo Verde. In a lyrical twist, the letters actually stand for Musica e Grogue: Music and Grog. Which is original, if nothing else, because artistic touches are not all that common in our world, and such touches are often dismissed as mere frippery meant to distract from a substandard product.

In this case, however Jean-Pierre Engelbach, who founded the company with local Cabo Verde grogue producer and music-lover Simão Évora, has an interesting background in the dramatic and musical arts, and was a singer, comedian and director on the French scene for decades…one can only wonder what drove him to amend his career at this late stage by taking a sharp U turn and heading into the undiscovered country of grogues, but for my money, we should not quibble, but be grateful that another fascinating branch of the Great Rum Tree has come to our attention. For what it’s worth, he told me he fell in love with Cabo Verde music a long time ago, leading to visits and a growing appreciation and love for the local rhums and eventually the two men chose to entwine their passions in the name of the company.

Anyway, this particular product is an unaged white, a grogue by the islands’ definitions (the only one that counts), derived from sugar cane in the Tarrafal village just south of Monte Trigo on the island of Santo Antão, the most north-westerly of the series of islands making up Cabo Verde..

Fire-fed pot still in Tarrafal. Photo (c) Musica e Grogue FB page

This one small village has five small artisanal distilleries (!!) that produce grogue in small quantities — about 20,000 liters annually — and M&G’s founders believe that the cane varietals there, combined with the climate and soil, produce a juice of exceptional quality. However, they only use a single preferred grogue-distiller for their juice, unlike Vulcão, also from here, which is a blend of three.

The production methods are straightforward: the cane, grown pesticide- and fertilizer-free, is crushed within 48 hours of harvesting, and fermentation is open air with natural from wild yeast for 10-15 days. The wash is then run through a fire-heated pot still, taken off at around 45% and is left to rest for a few weeks in 20 liter demi-johns known as a “Lady Jeanne” (also referred to as a Mama Juana or Dame Jeanne in Spanish and French speaking countries respectively). The peculiarity of this rest is that the large squat bottle in question is also stoppered with banana leaves, which “[…] allows the air to pass during the rest period of the grogue, necessary after the distillation,” said Jean-Pierre Engelbach, when I asked him.

Banana-leaf-stoppered demi-johns in which the grogue rests after distillation for 3-4 weeks. Photo (c) Musica e Grogue FB Page

That out of the way, what we had here, then, was a rhum made to many of the same general specifications as a French island agricole, while preserving its own unique production methodology and, hopefully, drinking profile. Did it succeed?

Oh yes. On smelling it for the first time, my initial notes read “subtly different” and within its strictures, it was. It initially seemed like a crisp-yet-gentle agricole, smelling cleanly of sweet sugar cane sap, vanilla, dill, green grapes and freshly mown grass, with a teasing note of brine and olives and a whiff of watered down vegetable soup fed to a jailbird in solitary. It was delicate and clear and different enough to hold the attention of anyone, nasal newbie or jaded rumdork, and the nice thing is, after five minutes it still was purring out aromas: flowers, cherries and pears, with a firm citrus line holding things together

While stronger and more individualistic drinks might be my personal preference these days, there was no denying that the Grogue Natural was a very pleasant drink, and I have a feeling I’ll be getting more of these things, as they provide a lovely counterpoint to agricoles in general. It tasted light, grassy, herbal, sweetish (without actually being sweet, if you catch my drift), with hints of watery sap, cane juice, cucumbers, an olive or two, and lots of light fruits – guavas, pears, soursop, ginnip, that kind of thing, and again, that lemon zest providing a clothesline on which to hang the lot. Finish was long and silky, surprising for something bottled at a modest 44%, but you don’t hear me complaining – it was just fine.

It’s become a sort of personal hobby for me to try unaged white rums of late, because while I love the uber-aged stuff, they do take flavours from the barrel and lose something of their original character, becoming delicious but changed spirits. On the other hand, unaged blancs or blancos — white rums — when not filtered to nothingness for the clueless, are about as close to pure and authentic rums as anyone’s going to get these days, and Cabo Verde’s stuff is among the most authentic of the lot.

It’s become a sort of personal hobby for me to try unaged white rums of late, because while I love the uber-aged stuff, they do take flavours from the barrel and lose something of their original character, becoming delicious but changed spirits. On the other hand, unaged blancs or blancos — white rums — when not filtered to nothingness for the clueless, are about as close to pure and authentic rums as anyone’s going to get these days, and Cabo Verde’s stuff is among the most authentic of the lot.

The Cap-Vert Grogue Natural that M. Jean-Pierre and Sr. Simão are making is one of these that need to be tried for that reason alone, quite aside from its overall drinkability. Sure it lacks the meticulous clarity of the French agricoles, and you’d never mistake it for a cachaca or a clairin or a Paranubes, but the relative isolation and old-style production methods of these music-loving Cabo Verde producers have assured us of a really interesting juice here, which deserves to become much more well known than it yet is. And drunk, of course. Yes. Preferably after a hard day’s work, as the sun goes down, while relaxing to the sounds of some really good island music.

(#634)(83/100)

Additional background

The company was formed in 2017 by the two gentlemen named above, who were drawn together by their mutual love of music and local rhum. But it was not until 2018 that they received the formal licenses permitting them to export grogues and started shipping some to Europe. This delay may have to do with the fact that hundreds of small moonshineries and primitive stills – nearly four hundred by one estimate – are scattered across Cabo Verde islands, with wildly varying quality of output. Indeed, according to one news report by the Expresso das Ilhas (Island Express), some 10 million liters of spirit calling it self “grogue” was marketed in 2017, but less than half of that could legitimately term itself so, since it was not made from sugar cane, and there were issues of hygiene and quality control to consider.

Be that as it may, M&G were able to navigate the new bureaucratic, quality and legal hurdles, obtain the requisite licenses and permits, and produced two grogues for the export market: the lightly-aged Velha we’ll be looking at soon, and the Natural.

Other Notes

- M&G and Vulcão are among the frist brands to export grogue from Cabo Verde

- M&G also makes some flavoured punches at a lower 18% strength

- Maison Ferroni, which is the brand owner for the Vulcão, is the distributor for M&G

- This bottle is part of the first release, and is something of a pilot project for the company’s export plans….hence the limited edition of 639 bottles. It’s not special per se, just part of a batch of the first four hundred liters or so which they exported.

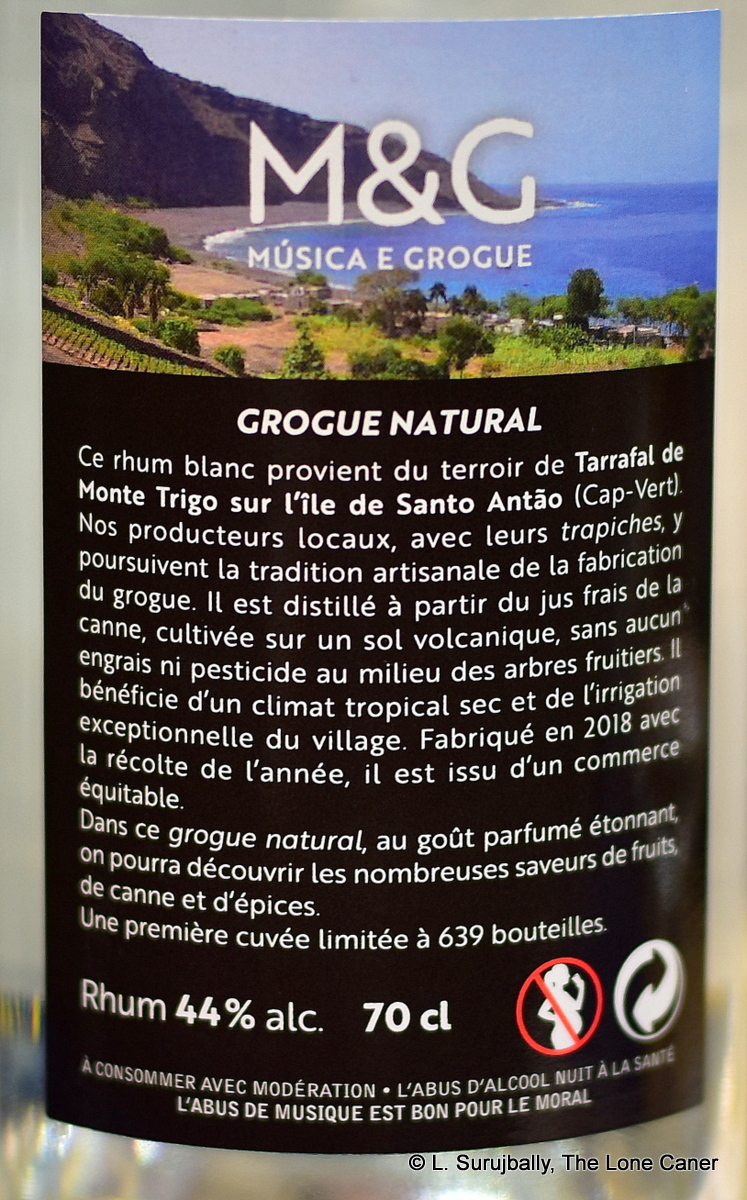

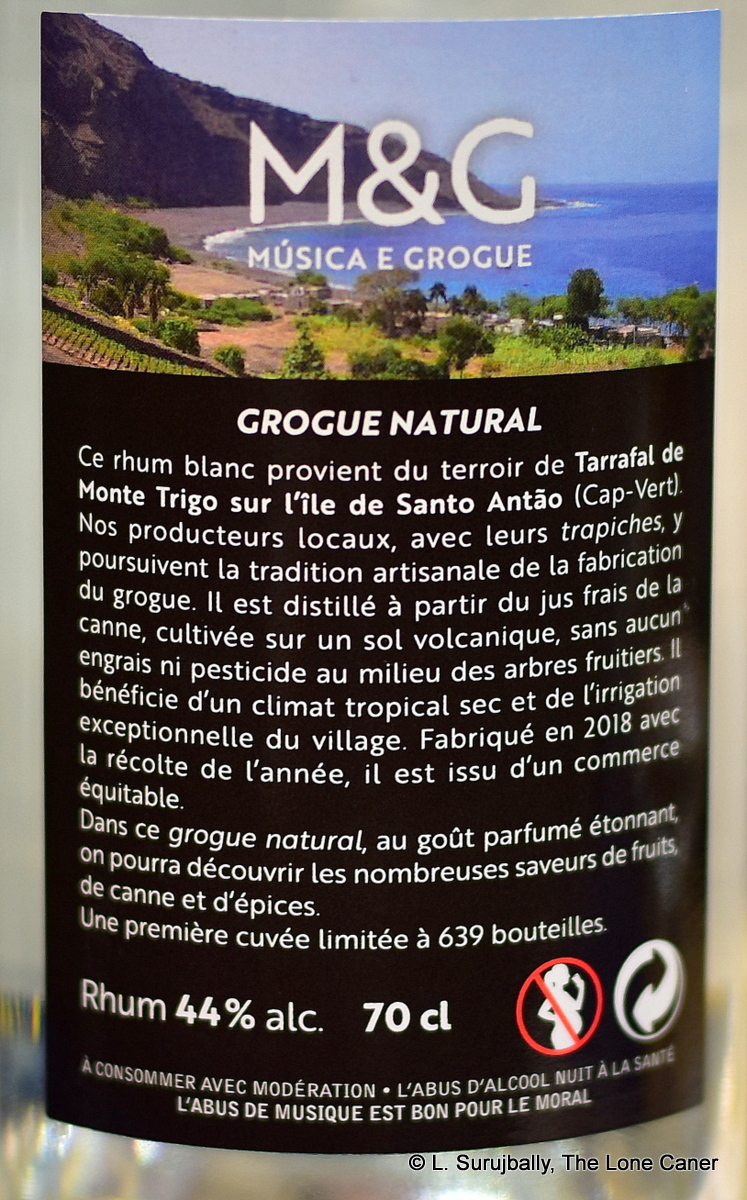

- Back label translation:

This white rum comes from the Tarrafal terroir of Monte Trigo on the island of Santa Antao (Cape Verde). Our local producers, with their trapiches, continue the artisanal tradition of making grogue. It is distilled from fresh cane juice, cultivated on volcanic soil in the middle of fruit trees, without any fertilizer or pesticide. It benefits from a dry tropical climate and the exceptional irrigation of the village. Made in 2018 with the harvest of the year, it is a fair trade product.

In this natural grogue, with its amazing flavor, we can discover the many flavors of cane fruits and spices.

A first release limited to 639 bottles

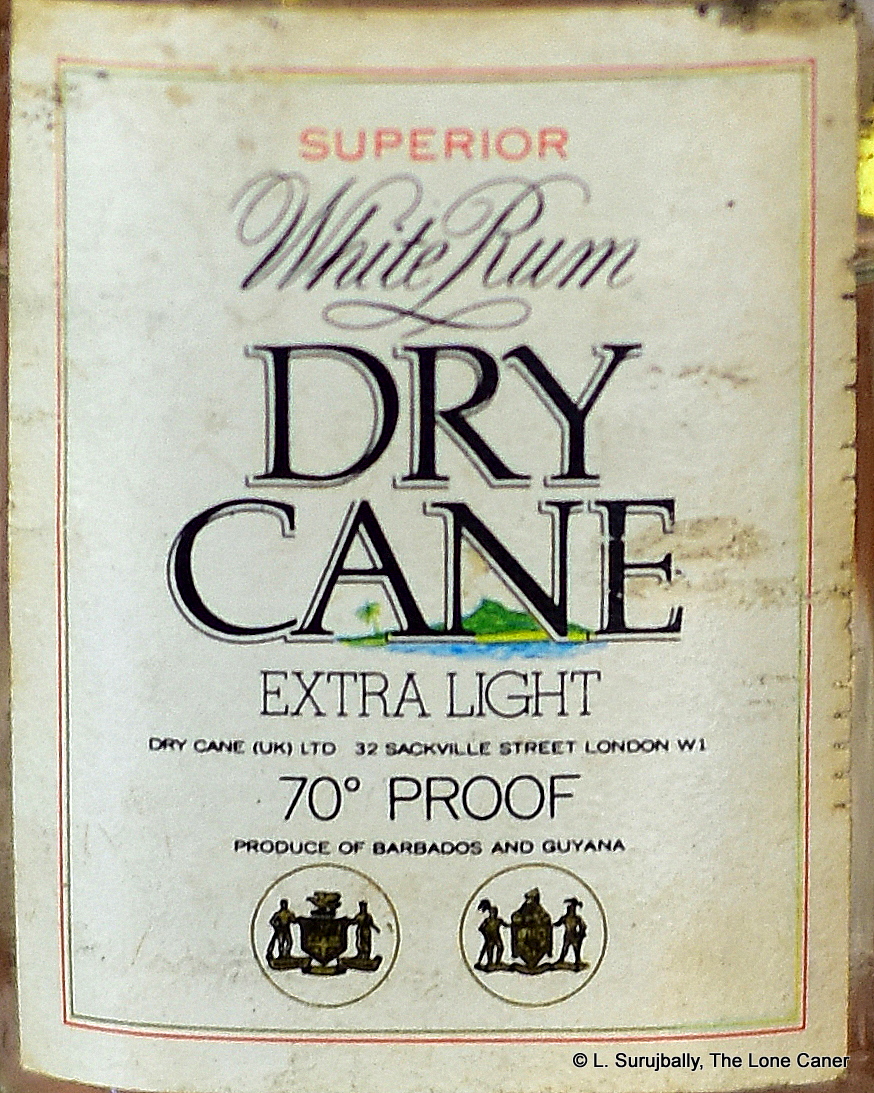

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale. Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

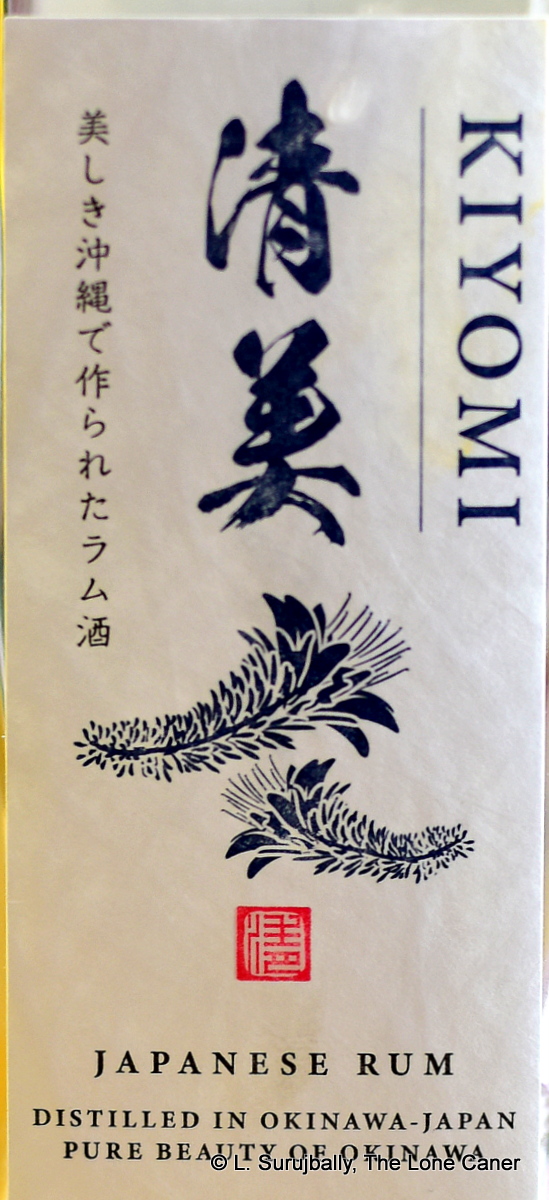

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages (

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages ( The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

Whatever the case, the rum was as fierce as the Diamond, and even at a microscopically lower proof, it took no prisoners. It exploded right out of the glass with sharp, hot, violent aromas of tequila, rubber, salt, herbs and really good olive oil. If you blinked you could see it boiling. It swayed between sweet and salt, between soya, sugar water, squash, watermelon, papaya and the tartness of hard yellow mangoes, and to be honest, it felt like I was sniffing a bottle shaped mass of whup-ass (the sort of thing Guyanese call “regular”).

Whatever the case, the rum was as fierce as the Diamond, and even at a microscopically lower proof, it took no prisoners. It exploded right out of the glass with sharp, hot, violent aromas of tequila, rubber, salt, herbs and really good olive oil. If you blinked you could see it boiling. It swayed between sweet and salt, between soya, sugar water, squash, watermelon, papaya and the tartness of hard yellow mangoes, and to be honest, it felt like I was sniffing a bottle shaped mass of whup-ass (the sort of thing Guyanese call “regular”).

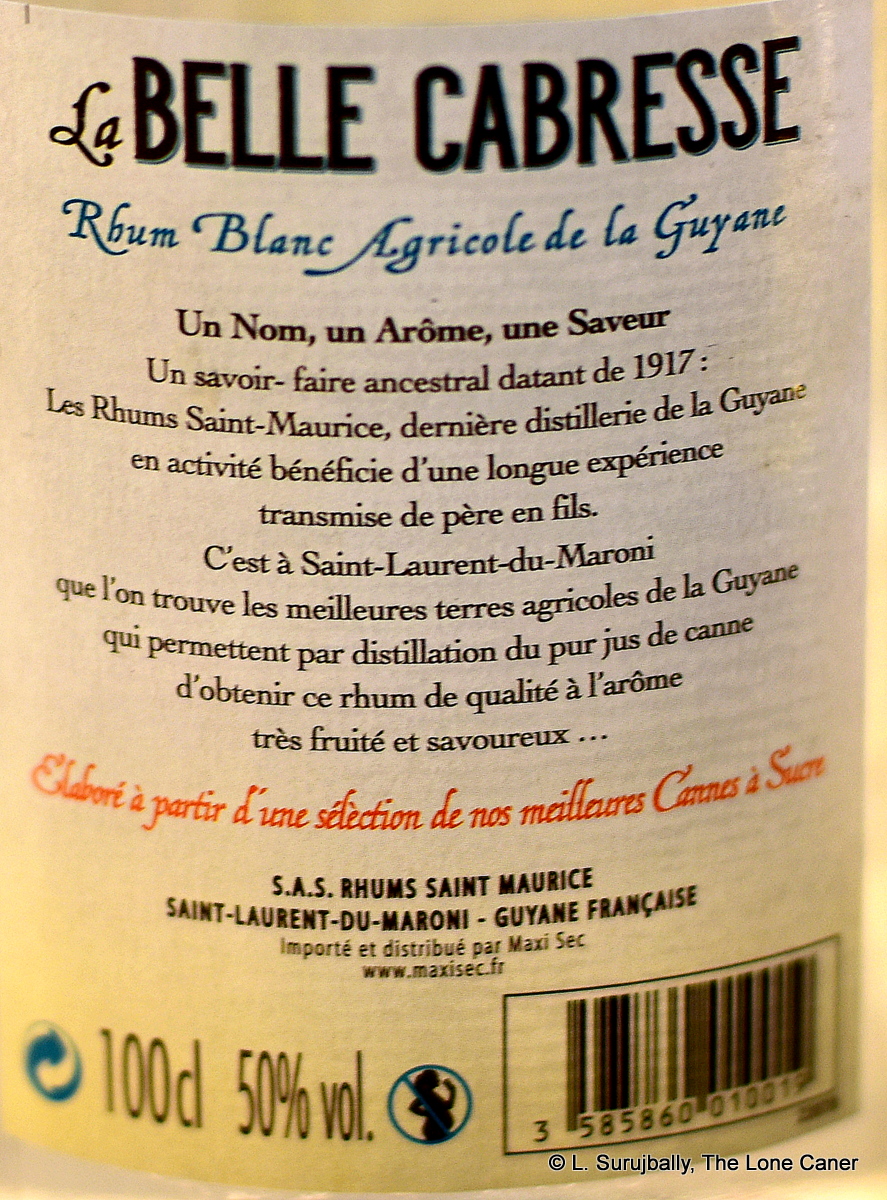

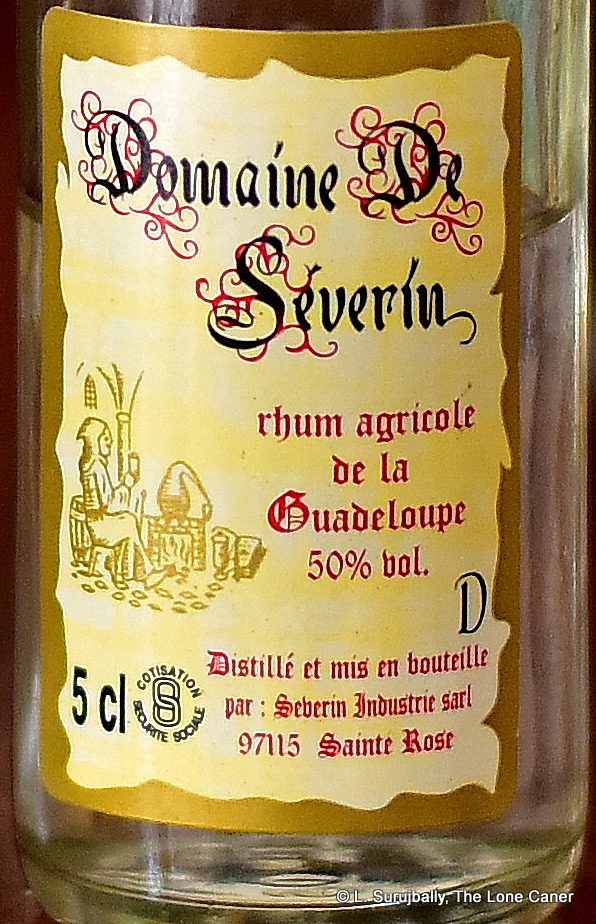

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

And also because, man, did this thing ever smell pungent — it was a bottle-sized 60-proof ode to whup-ass and rumstink. A barrage of nail polish, spoiling fruit, wood chips, wax, salt, and gluey notes all charged right out without pause or hesitation, spoiling for a fight. Even without making a point of it, the rhum unfolded with uncommon firmness into aromas of sweet, grassy herbals, green apples, sugar water, dill, cider, vegetables, toasted bread, a sharp mature cheddar, all mixed in with moist dark earth, sugar water, biscuits, orange peel. And the balance of all of them was really quite good, truly.

And also because, man, did this thing ever smell pungent — it was a bottle-sized 60-proof ode to whup-ass and rumstink. A barrage of nail polish, spoiling fruit, wood chips, wax, salt, and gluey notes all charged right out without pause or hesitation, spoiling for a fight. Even without making a point of it, the rhum unfolded with uncommon firmness into aromas of sweet, grassy herbals, green apples, sugar water, dill, cider, vegetables, toasted bread, a sharp mature cheddar, all mixed in with moist dark earth, sugar water, biscuits, orange peel. And the balance of all of them was really quite good, truly.

I’ll get straight to it, then, and merely mention that at 85% ABV, care was taken – I poured, covered the glass, waited, removed the cover, and prudently stepped way back.

I’ll get straight to it, then, and merely mention that at 85% ABV, care was taken – I poured, covered the glass, waited, removed the cover, and prudently stepped way back.

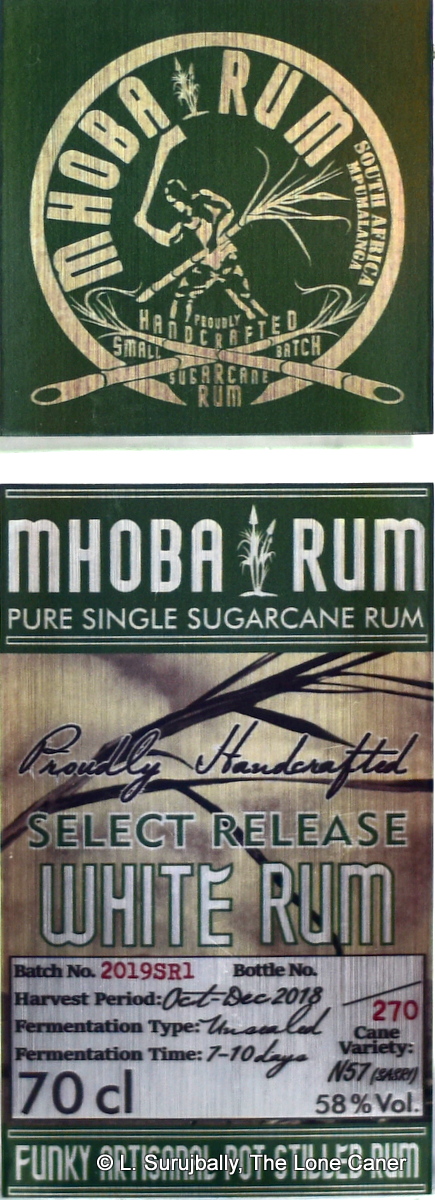

I’ll leave you to peruse Steve’s enormously informative company profile for production details (it’s really worth reading just to see what it takes to start something like a craft distillery), and just mention that the rum is pot still distilled from juice which is initially fermented naturally before boosting it with a strain of commercial yeast. The company makes three different kinds of white rums – pot still white, high ester white and a blended white, all unaged. I tried what is probably the tamest of the three, the Select, which the last one, blended from several cuts taken from batches processed between October to December of 2018 and bottled at 58%. All of this is clearly marked on the onsite-produced label (self-engraved, self-printed, manually-applied), which is one of the most informative on the market: it details batch number, date, strength, variety of cane, still, number of bottles in the run…it’s really impressive work.

I’ll leave you to peruse Steve’s enormously informative company profile for production details (it’s really worth reading just to see what it takes to start something like a craft distillery), and just mention that the rum is pot still distilled from juice which is initially fermented naturally before boosting it with a strain of commercial yeast. The company makes three different kinds of white rums – pot still white, high ester white and a blended white, all unaged. I tried what is probably the tamest of the three, the Select, which the last one, blended from several cuts taken from batches processed between October to December of 2018 and bottled at 58%. All of this is clearly marked on the onsite-produced label (self-engraved, self-printed, manually-applied), which is one of the most informative on the market: it details batch number, date, strength, variety of cane, still, number of bottles in the run…it’s really impressive work.

It’s become a sort of personal hobby for me to try unaged white rums of late, because while I love the uber-aged stuff, they do take flavours from the barrel and lose something of their original character, becoming delicious but changed spirits. On the other hand, unaged

It’s become a sort of personal hobby for me to try unaged white rums of late, because while I love the uber-aged stuff, they do take flavours from the barrel and lose something of their original character, becoming delicious but changed spirits. On the other hand, unaged

I’ve never been completely clear as to what effect a resting period in neutral-impact tanks would actually have on a rum – perhaps smoothen it out a bit and take the edge off the rough and sharp straight-off-the-still heart cuts. What is clear is that here, both the time and the reduction gentle the spirit down without completely losing what makes an unaged white worth checking out. Take the nose: it was relatively mild at 40%, but retained a brief memory of its original ferocity, reeking of wet soot, iodine, brine, black olives and cornbread. A few additional nosings spread out over time reveal more delicate notes of thyme, mint, cinnamon mingling nicely with a background of sugar water, sliced cucumbers in salt and vinegar, and watermelon juice. It sure started like it was out to lunch, but developed very nicely over time, and the initial sniff should not make one throw it out just because it seems a bit off.

I’ve never been completely clear as to what effect a resting period in neutral-impact tanks would actually have on a rum – perhaps smoothen it out a bit and take the edge off the rough and sharp straight-off-the-still heart cuts. What is clear is that here, both the time and the reduction gentle the spirit down without completely losing what makes an unaged white worth checking out. Take the nose: it was relatively mild at 40%, but retained a brief memory of its original ferocity, reeking of wet soot, iodine, brine, black olives and cornbread. A few additional nosings spread out over time reveal more delicate notes of thyme, mint, cinnamon mingling nicely with a background of sugar water, sliced cucumbers in salt and vinegar, and watermelon juice. It sure started like it was out to lunch, but developed very nicely over time, and the initial sniff should not make one throw it out just because it seems a bit off.

Consider first the nose of this

Consider first the nose of this

Nose – Starts off with plastic, rubber and acetones, which speak to its (supposed) unaged nature; then it flexes its cane-juice-glutes and coughs up a line of sweet water, bright notes of grass, sugar cane sap, brine and sweetish red olives. It’s oily, smooth and pungent, with delicate background notes of dill and cilantro lurking in the background. And some soda pop.

Nose – Starts off with plastic, rubber and acetones, which speak to its (supposed) unaged nature; then it flexes its cane-juice-glutes and coughs up a line of sweet water, bright notes of grass, sugar cane sap, brine and sweetish red olives. It’s oily, smooth and pungent, with delicate background notes of dill and cilantro lurking in the background. And some soda pop.