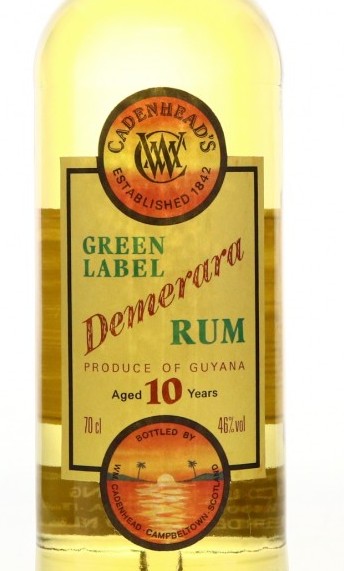

As noted before (and repeated below for the curious), Cadenhead has three different bottle ranges, each of which has progressively less information than the one before it: the Dated Distillations, the Green Labels and the Caribbean blends.

The Green Label releases are always 46% and issued on no schedule; their labels and the company website provides so little information on past releases that one has to take some stuff on faith — in this case, my friend Sascha Junkert (the sample originator) noted it was a 10 YO bottled in 2000, although even the best resource on Cadenhead’s older bottlings, Marco Freyr, cannot verify the dates in his detailed post on the company and the accompanying bottle list, and Rum-X only mentions one distilled in 1998. There are only a handful of Green Label 10 YO rums from Guyana / Demerara at all, and the 2000 reported date doesn’t line up for any other published resource – when they bother, most mention 1998-2002 as distillation dates. So some caution is in order.

What’s particularly irritating about the label in this instance is that it lacks any information not only about the dates and the still(s), but also the casks – and so here one has to be careful, because there are two types of this 10YO Demerara: one “standard” release, and one matured in Laphroaig casks. How to tell the difference? The Laph aged version is much paler and has a strip taped vertically across the screw top like a tax strip. Hardly the epitome of elegant and complete information provision now, is it.

Colour – Pale yellow

Strength – 46%

Nose – Dry, dusty, with notes of anise and rotting fruits: one can only wonder what still this came off of. Salt butter, licorice, leather, tannins and smoke predominate, but there is little rich dark fruitiness in evidence. Some pencil shavings, sawdust, glue and acetone, and the bite of unsweetened tea that’s too strong.

Palate – Continues the action of the sweet bubble gum, acetones, nail polish and glue, plus some plasticine – not unpleasant, just not very rum-like. Also the pencil shavings, sawdust and varnish keep coming, and after a while, some green fruits: apples, soursop, grapes. At the last, one can sense candied oranges, caramel bon bons, and more very strong and barely-sweetened black tea teetering on the edge of bitterness.

Finish – Reasonably long, reasonably flavourful, quite thin. Mostly licorice, caramel, tannins and a touch of unidentifiable fruit.

Thoughts – It’s not often appreciated how much we pre-judge and line up our expectations for a rum based on what we are told about it, or what’s on the label. Here it’s frustrating to get so little, but it does focus the attention and allow an unblinking, cold-eyed view to be expressed. In fine, it’s an average product: quite drinkable, decent strength, enough flavours not to bore, too few to stand out in any way. It’s issued for the mid range, and there it resolutely stays, seeking not to rise above its station

(82/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

- The three ranges of Cadenhead’s releases are:

- The cask strength, single-barrel Dated Distillation series with a three- or four-letter identifier and lots of detail on source and age; I submit these are probably the best and rightly the most sought-after rums from the company (aside from a 1939-distilled Green Label from Ago). The only question usually remaining when you get one, is what the letters stand for.

- The Green Label series; these are usually single-country blends, sometimes from multiple distilleries (or stills, or both), mostly from around the Caribbean and Central/South America; a few other countries have been added in the 2020s. Here you get less detail than the DDs, mostly just the country, the age and the strength, which is always 46% ABV. THey had puke yellow labels with green and red accents for a long time, but now they’re green for real, as they had been back in the beginning.

- Classic Blended Rum; a blend of Caribbean rums, location never identified, age never stated (anywhere), usually bottled at around 50% ABV. You takes your chances with these, and just a single one ever crossed my path.

- Strictly speaking there is a fourth type sometimes referred to as a “Living Cask” which is a kind of personalized shop-by-shop infinity bottle. I’ve only tried one of these, though several are supposedly in existence.

- These older Cadenhead’s series with the puke yellow and green labels are a vanishing breed so I think the classification in the Rumaniacs is appropriate.

- The pot-column still tagging / categorization is an assumption based on the way it tasted. I think it’s an Enmore and Versailles blend, but again, no hard evidence aside from my senses.

Rumaniacs Review #123 | #800

Rumaniacs Review #123 | #800

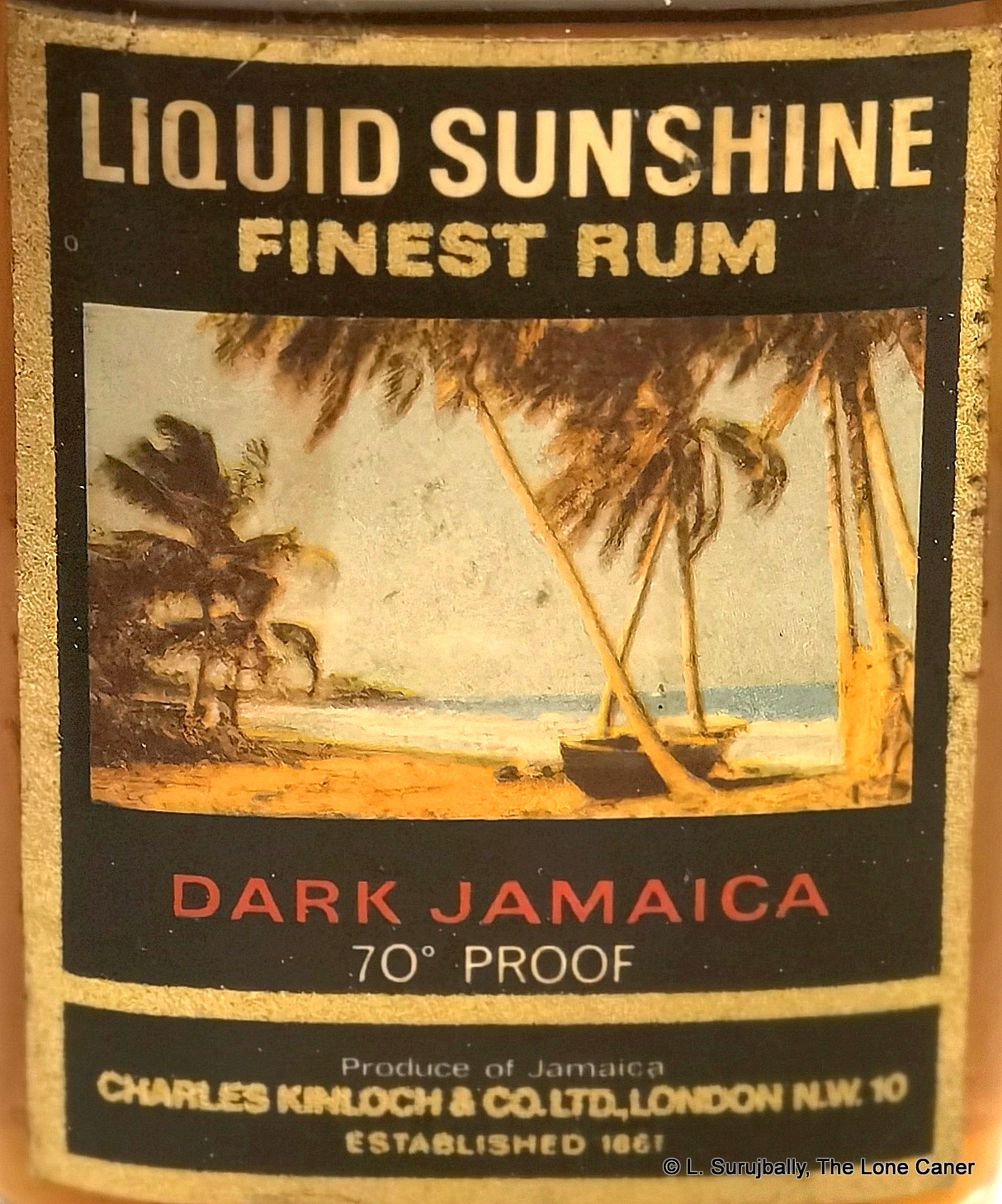

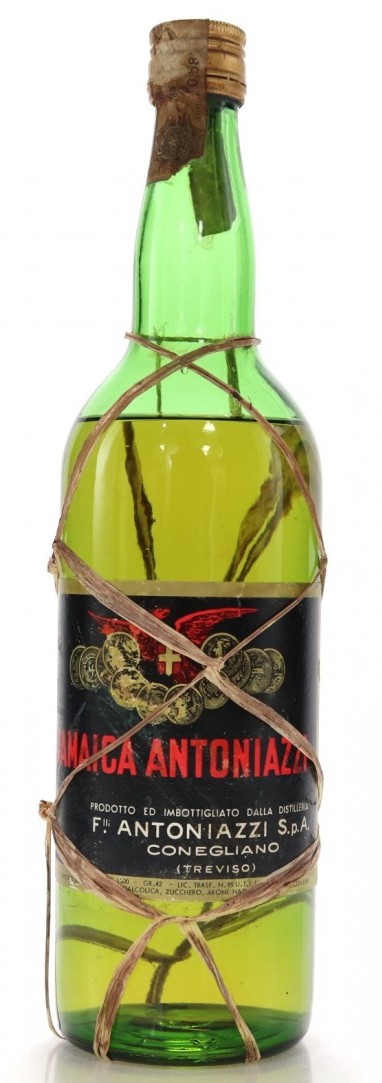

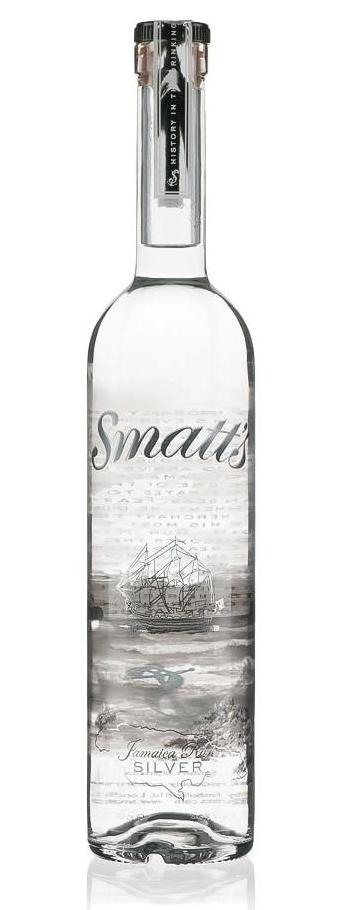

Normally, such a rum wouldn’t interest me much, but with the massive reputations the New Jamaicans have been building for themselves, it made me curious so I grudgingly parted with some coin to get a sample. That was the right decision, because this thing turned out to be less an undiscovered steal than a low-rent Jamaican wannabe for those who don’t care about and can’t tell one Jamaican rum from another, know Appleton and stop there. The rum takes great care not to go beyond such vanilla illusions, since originality is not its forte and it takes inoffensive pleasing-the-sipper as its highest goal.

Normally, such a rum wouldn’t interest me much, but with the massive reputations the New Jamaicans have been building for themselves, it made me curious so I grudgingly parted with some coin to get a sample. That was the right decision, because this thing turned out to be less an undiscovered steal than a low-rent Jamaican wannabe for those who don’t care about and can’t tell one Jamaican rum from another, know Appleton and stop there. The rum takes great care not to go beyond such vanilla illusions, since originality is not its forte and it takes inoffensive pleasing-the-sipper as its highest goal.

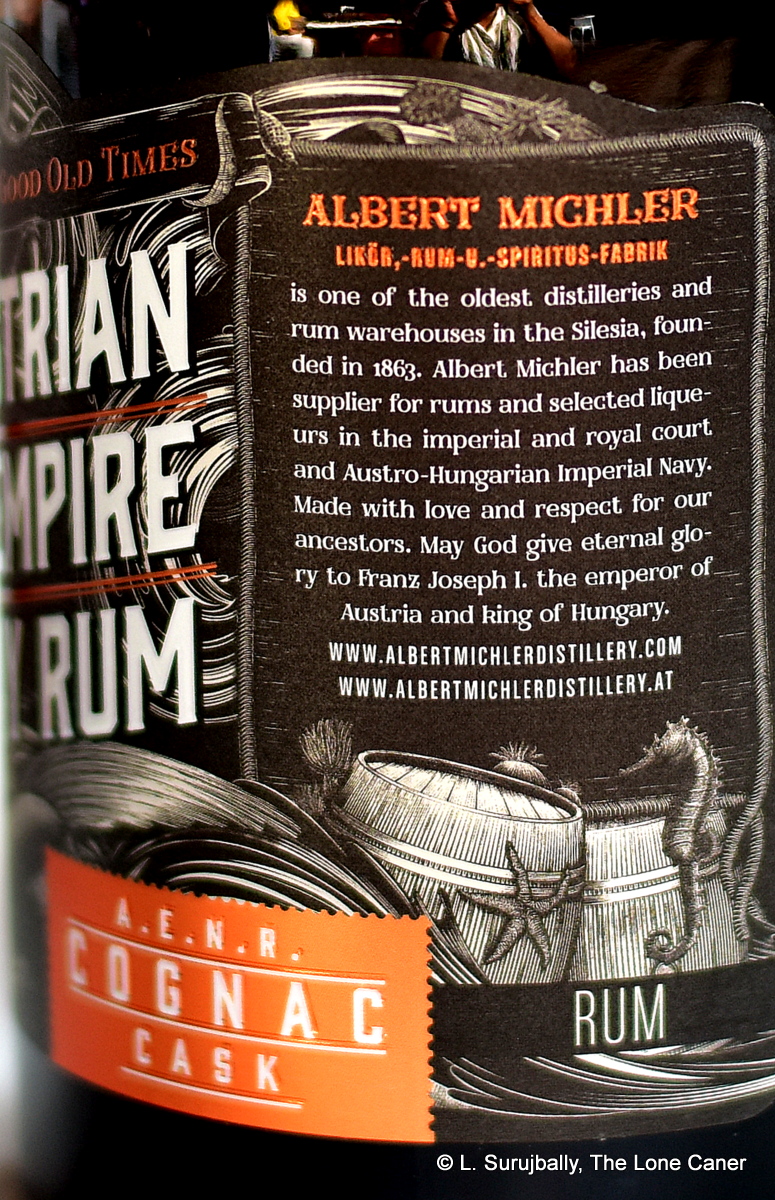

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum

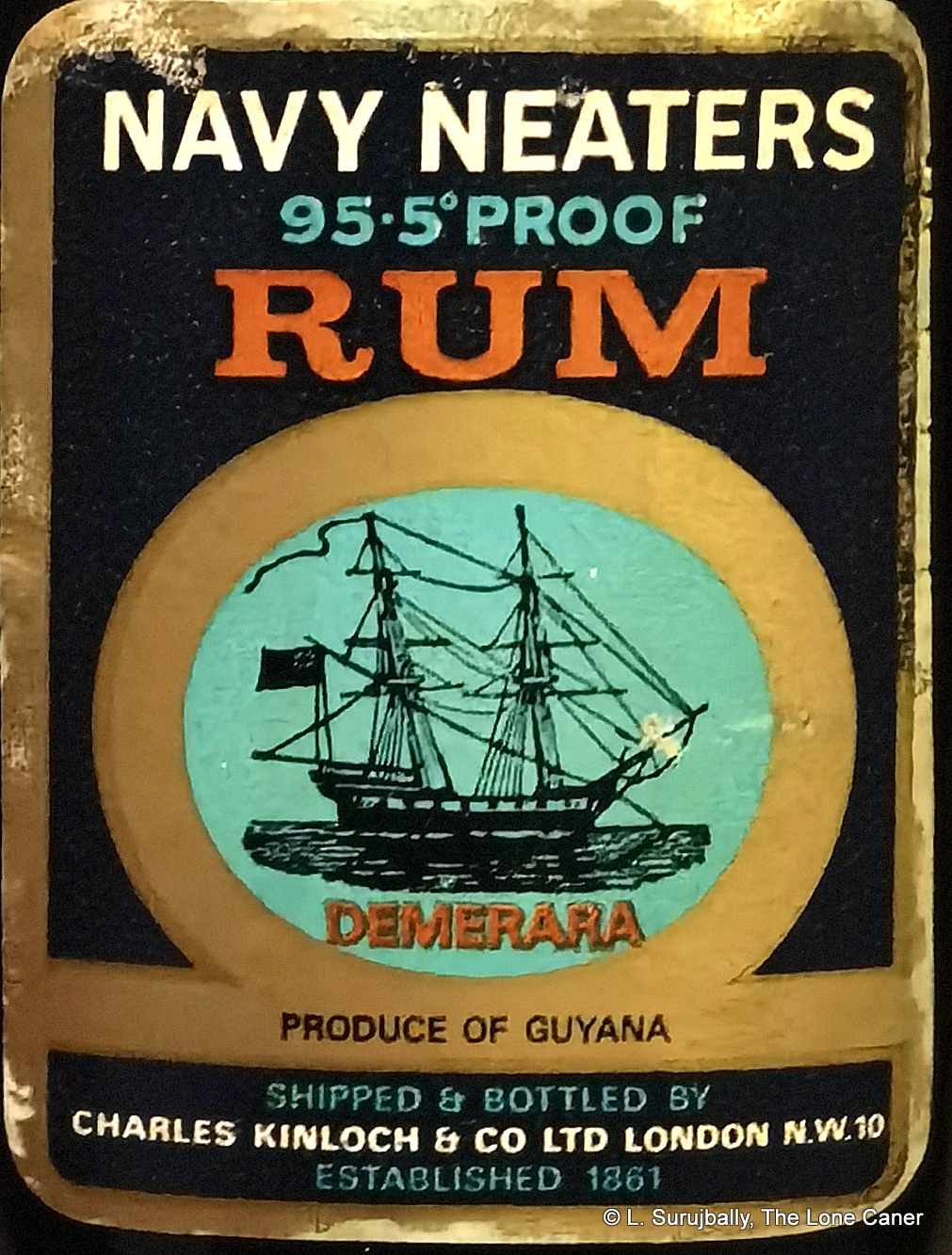

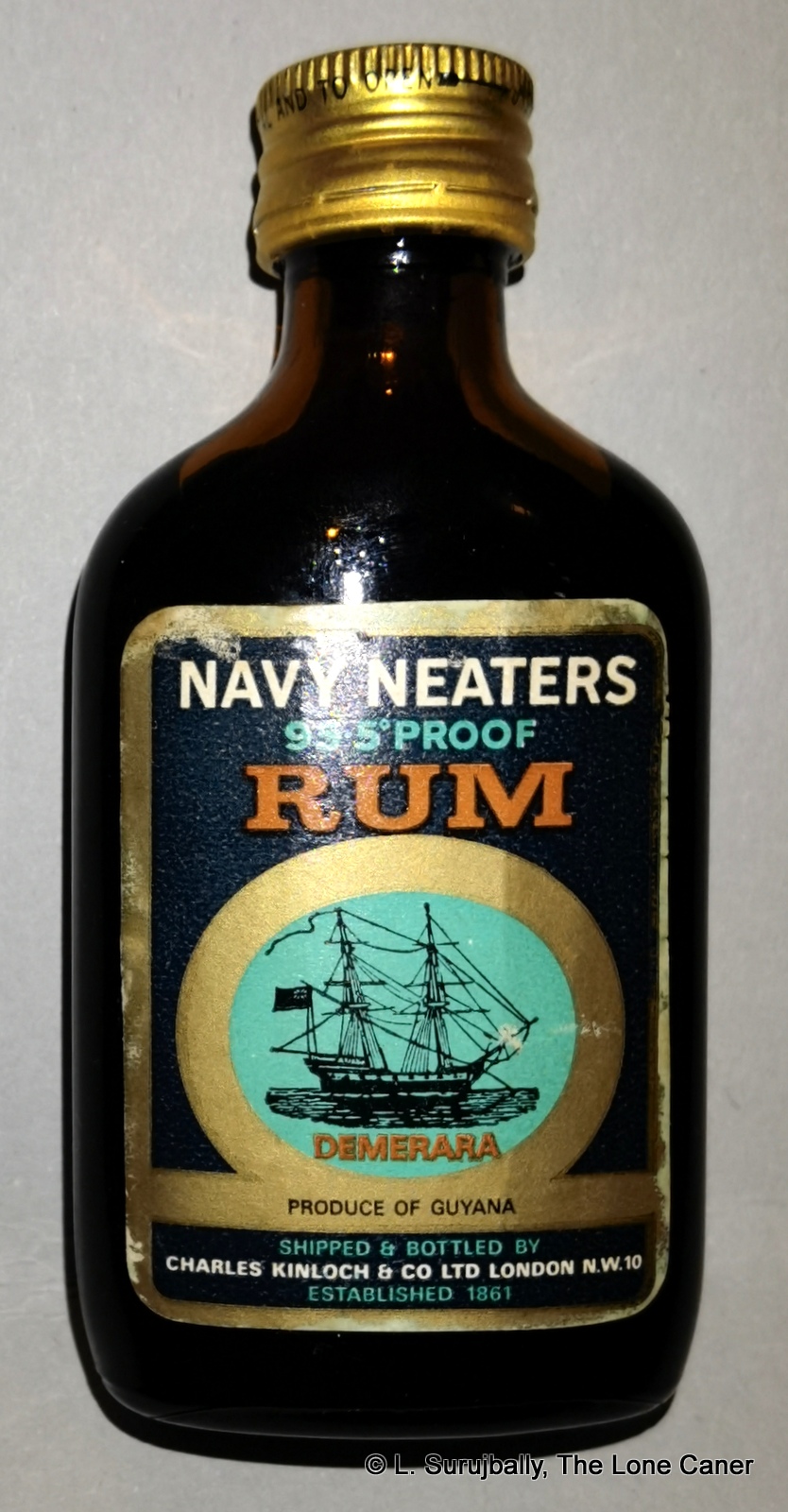

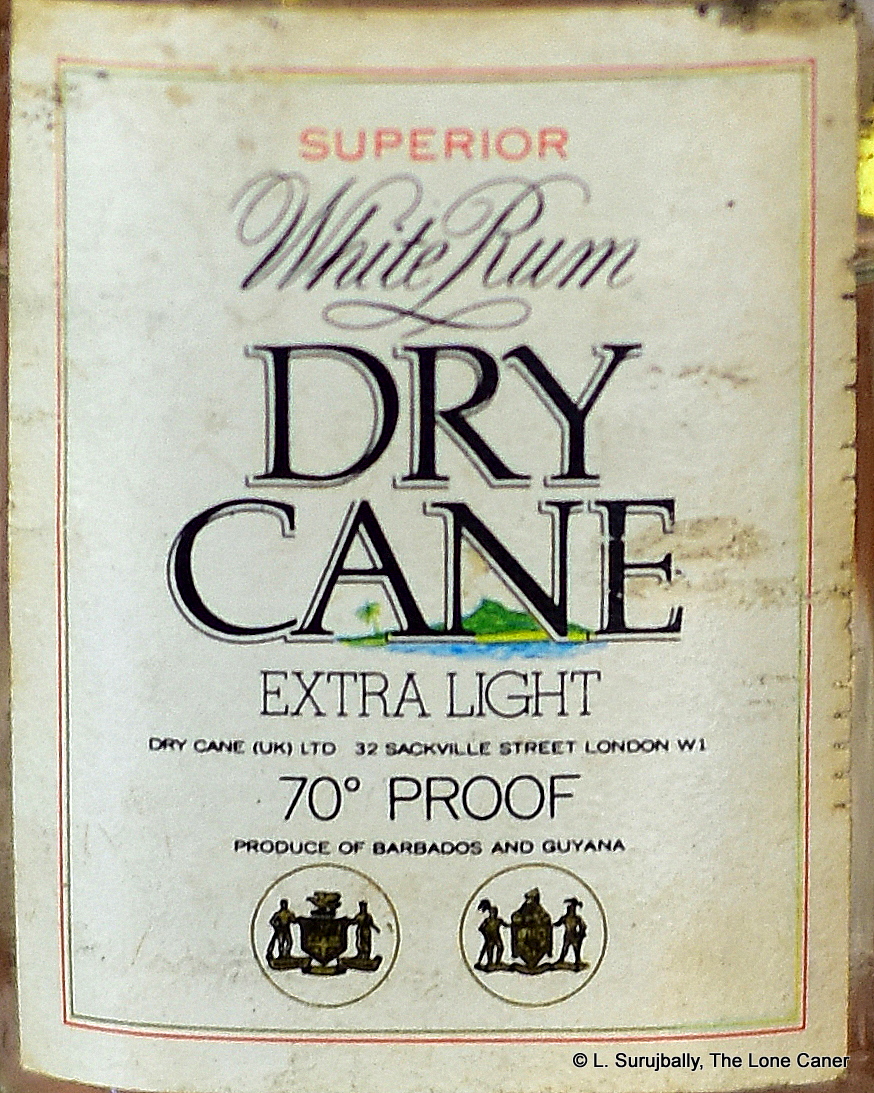

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale. Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

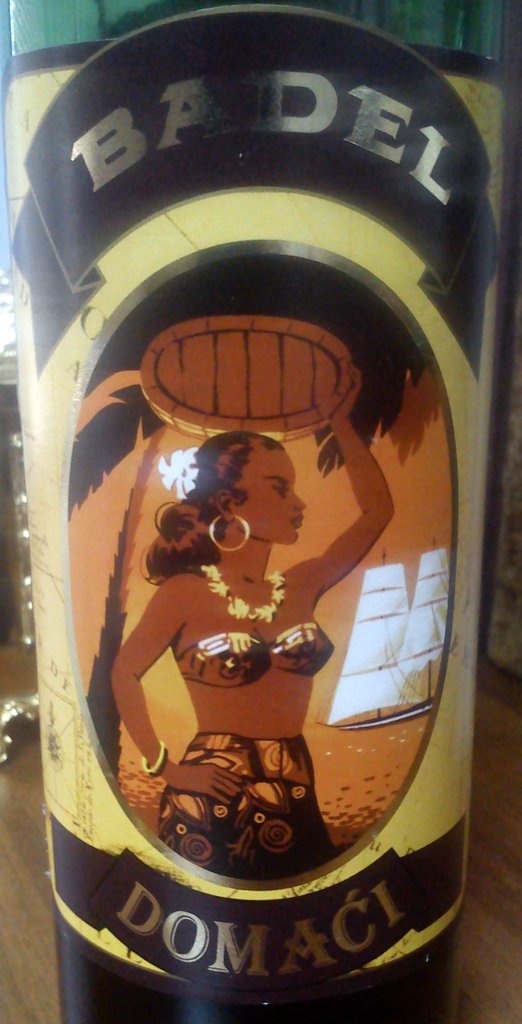

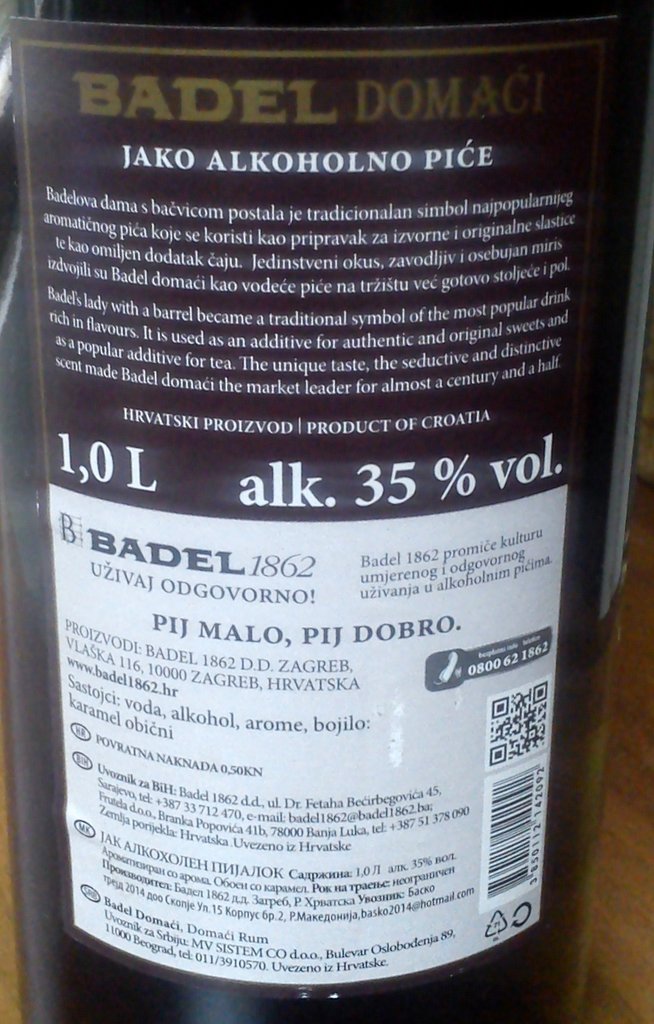

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of