The rum starts slowly. I don’t get much at the inception. Bananas, ripe; pineapples, oversweet; papayas, dark cherries, nice….and a touch of beetroot, odd. Not my thing, this rather thin series of tastes — it develops too lethargically, is too dim, lacks punch. I wait ten minutes more to make sure I’m not overreacting…perhaps there’s more? Well, yes and no. These aromas fade somewhat, to be replaced by something sprightly and sparkling – fanta, sprite, red grapefruit, lemon zest – but overall the integration is poor, and doesn’t meld well and remains too lazily easygoing, like some kind of clever class wiseass who couldn’t be bothered.

Palate is good, I like that, though perhaps a few extra points of strength would have been in order (my opinion – your own mileage will vary). Still, it’s tasty – vanilla, green peas, pears, cucumbers, watermelon, sapodilla and kiwi fruits, grapes. Low key, almost delicate, but well assembled, tasting nice and clean, a sipper’s delight for those who like reasonably complex faux-agricoles that are light and crisp and not dour, heavy brontosaurii of flavour that batten the glottis flat. The finish wraps things up with a flourish, and if short, it at least displays a lightly sweet and fruity melange that describes the overall profile well.

The distillery of origin of this Moon Imports’ 1998 Guadeloupe rum (from their “Moon Collection”) is something of a mystery, since the “GMP” in the title does not fit any descriptor with which I am familiar. It could possibly be Gardel, which Renegade quoted as a source with their 11 YO 1998 rum, also released at 46%…but Gardel supposedly shut down in 1992, and afterwards Damoiseau / Bellevue was said to have used the name for some limited 1998 releases. But it remains unclear and unproven, and so for the moment we have to leave that as an unresolved issue, which I’ll update when better info comes in.

(Photo taken from eBay; note that many Bellevue releases from Moon Import have almost exactly the same design)

Slightly more is known about Moon Import, the Italian company from Genoa that released it. Its origins dating back to 1980 when an entrepreneur named Pepi Mongiardino founded the company: he had worked for Pernod, Ballantine’s and Milton Duff in the 1970s, tasting and testing high end single malts. When that business took a downturn, he took some opportune advice from Sylvano Samaroli on how to set up a business of his own, and used a reference book to check which whiskies were not yet imported to Italy. He cold-called those, leading to his landing the contract to import Bruichladdich. Initial focus was (unsurprisingly) whiskies — however it soon branched out from there into many other spirits, including rum, which came on the scene around 1990, and it followed the tried and true path of the independent bottler, sourcing barrels from brokers (like Scheer) and ageing them in Scotland. Label design was often done by Pepi himself, popularizing the concept of consistent individual designs for “ranges” that others subsequently latched on to, and from the beginning he eschewed 40% ABV in favour of something higher, though he avoided the full proof cask strength rum-strength model Velier later made widespread.

That all out of the way, the core statistics of this rum are that it was column distilled in 1998 (but not in or by Gardel); probably from molasses as the word agricole is nowhere mentioned and Guadeloupe does use that source material in the off-season; aged in Scotland for twelve years and released in 2010, at a comfortable strength of 46% ABV. Like Samaroli and Mark Reynier at the old Renegade outfit, Mongiardino feels this strength preserves the suppleness of the spirit and the development of a middling age profile, while balancing it off against excessive fierceness when drunk.

By the standards of its time and his philosophy, I’d say he was spot on. That does not, however, make it a complete success in this time, or acceptable for all current palates, which seem to prefer something more aggressive, stronger, something more distinct, in order to garner huge accolades and higher scores. It’s a rum that opens slowly, easily — even lazily — and gives the impression of being “nothing in particular” at the inception. It develops well, but never really coalesces into a complete package where everything works. That makes it a rum I can enjoy sipping (up to a point), and is a good mid-range indie I just can’t endorse completely.

(#793)(84/100)

Other notes

- Thanks again to Nicolai Wachmann for the sample. The guy always has a few tucked in his bag for me to try when we get together at some rumfest or other. Remind me to bug him for a picture of the bottle.

- 360 bottle outturn

All that comes together in a rhum of uncommonly original aroma and taste. It opens with smells that confirm its provenance as an agricole, and it displays most of the hallmarks of a rhum from the blanc side (herbs, grassiness, crisp citrus and tart fruits)…but that out of the way, evidently feels it is perfectly within its rights to take a screeching ninety degree left turn into the woods. Woody and even meaty notes creep out, which seem completely out of place, yet somehow work. This all combines with salt, rancio, brine, and olives to mix it up some more, but the overall effect is not unpleasant – rather it provides a symphony of undulating aromas that move in and out, no single one ever dominating for long before being elbowed out of the way by another.

All that comes together in a rhum of uncommonly original aroma and taste. It opens with smells that confirm its provenance as an agricole, and it displays most of the hallmarks of a rhum from the blanc side (herbs, grassiness, crisp citrus and tart fruits)…but that out of the way, evidently feels it is perfectly within its rights to take a screeching ninety degree left turn into the woods. Woody and even meaty notes creep out, which seem completely out of place, yet somehow work. This all combines with salt, rancio, brine, and olives to mix it up some more, but the overall effect is not unpleasant – rather it provides a symphony of undulating aromas that move in and out, no single one ever dominating for long before being elbowed out of the way by another.

I was really and pleasantly surprised by how well it presented, to be honest. For a standard strength rhum, I expected less, but its complexity and changing character eventually won me over. Looking at others’ reviews of rhums in Reimonenq’s range I see similar flip flops of opinion running through them all. Some like one or two, some like that one more than that other one, there are those that are too dry, too sweet, too fruity (with a huge swing of opinion), and the little literature available is a mess of ups and downs.

I was really and pleasantly surprised by how well it presented, to be honest. For a standard strength rhum, I expected less, but its complexity and changing character eventually won me over. Looking at others’ reviews of rhums in Reimonenq’s range I see similar flip flops of opinion running through them all. Some like one or two, some like that one more than that other one, there are those that are too dry, too sweet, too fruity (with a huge swing of opinion), and the little literature available is a mess of ups and downs.

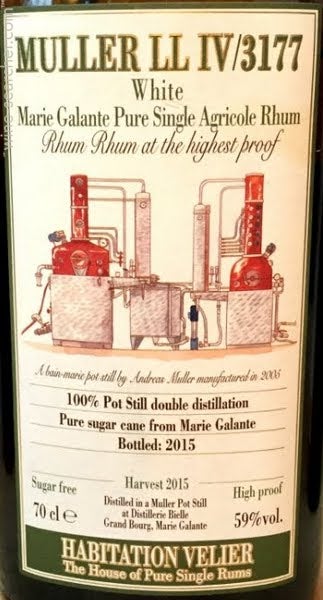

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.

So let’s spare some time to look at this rather unique white rum released by Habitation Velier, one whose brown bottle is bolted to a near-dyslexia-inducing name only a rum geek or still-maker could possibly love. And let me tell you, unaged or not, it really is a monster truck of tastes and flavours and issued at precisely the right strength for what it attempts to do.

So let’s spare some time to look at this rather unique white rum released by Habitation Velier, one whose brown bottle is bolted to a near-dyslexia-inducing name only a rum geek or still-maker could possibly love. And let me tell you, unaged or not, it really is a monster truck of tastes and flavours and issued at precisely the right strength for what it attempts to do. Evaluating a rum like this requires some thinking, because there are both familiar and odd elements to the entire experience. It reminds me of

Evaluating a rum like this requires some thinking, because there are both familiar and odd elements to the entire experience. It reminds me of

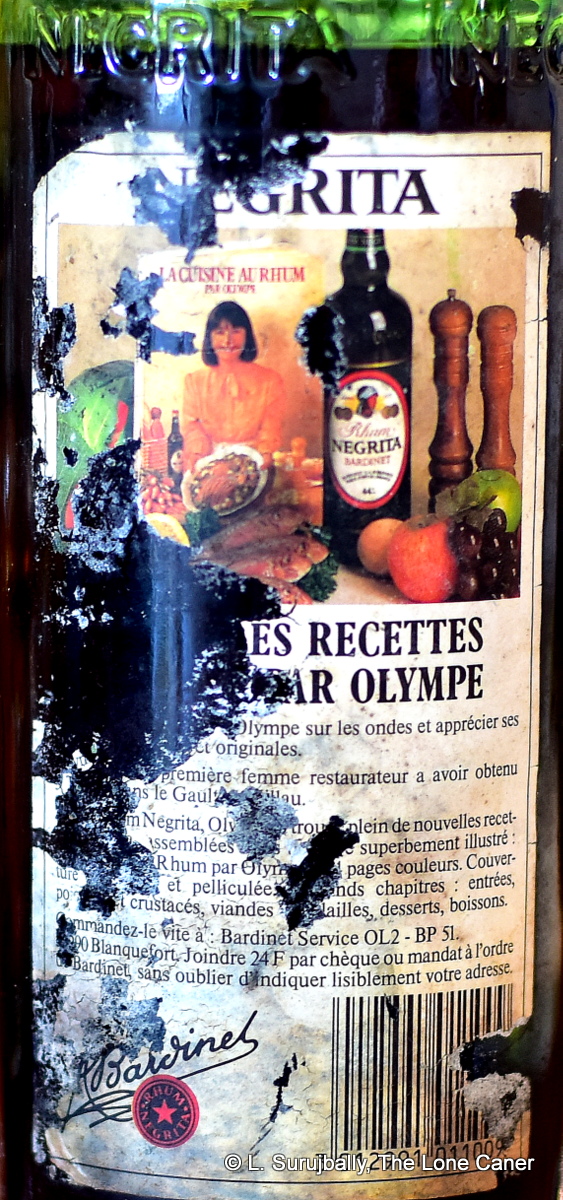

Nose – Doesn’t lend itself to quick identification at all. It’s of course pre-AOC so who knows what made it up, and the blend is not disclosed, alas. So, it’s thick, fruity and has that taste of a dry dark-red wine. Some fruits – raisins and prunes and blackberries – brown sugar, molasses, caramel, and a sort of sly, subtle reek of gaminess winds its way around the back end. Which is intriguing but not entirely supportive of the other aspects of the smell.

Nose – Doesn’t lend itself to quick identification at all. It’s of course pre-AOC so who knows what made it up, and the blend is not disclosed, alas. So, it’s thick, fruity and has that taste of a dry dark-red wine. Some fruits – raisins and prunes and blackberries – brown sugar, molasses, caramel, and a sort of sly, subtle reek of gaminess winds its way around the back end. Which is intriguing but not entirely supportive of the other aspects of the smell.

The palate was about par for the course for a rum bottled at this strength. Initially it felt like it was weak and not enough was going on (as if the profile should have emerged on some kind of schedule), but it was just a slow starter: it gets going with citrus, vanilla, flowers, a lemon meringue pie, plums and blackberry jam. This faded out and is replaced by sugar cane sap, swank and the grassy vegetal notes mixed up with ashes (!!) and burnt sugar. Out of curiosity I added some water , and was rewarded with citrus, lemon-ginger tea, the tartness of ripe gooseberries, pimentos and spanish olives. It took concentration and time to tease them out, but they were, once discerned, quite precise and clear. Still, strong they weren’t (“forceful” would not be an adjective used to describe it) and as expected the finish was easygoing, a bit crisp, with light fruit, fleshy and sweet and juicy, quite ripe, not so much citrus this time. The grassy and herbal notes are very much absent by this stage, replaced by a woody and spicy backnote, medium long and warm

The palate was about par for the course for a rum bottled at this strength. Initially it felt like it was weak and not enough was going on (as if the profile should have emerged on some kind of schedule), but it was just a slow starter: it gets going with citrus, vanilla, flowers, a lemon meringue pie, plums and blackberry jam. This faded out and is replaced by sugar cane sap, swank and the grassy vegetal notes mixed up with ashes (!!) and burnt sugar. Out of curiosity I added some water , and was rewarded with citrus, lemon-ginger tea, the tartness of ripe gooseberries, pimentos and spanish olives. It took concentration and time to tease them out, but they were, once discerned, quite precise and clear. Still, strong they weren’t (“forceful” would not be an adjective used to describe it) and as expected the finish was easygoing, a bit crisp, with light fruit, fleshy and sweet and juicy, quite ripe, not so much citrus this time. The grassy and herbal notes are very much absent by this stage, replaced by a woody and spicy backnote, medium long and warm

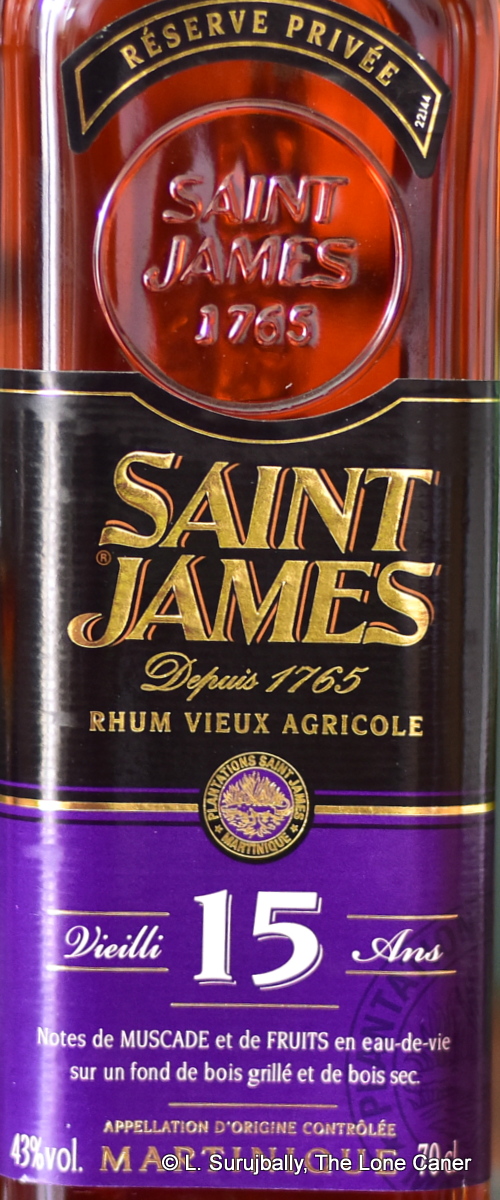

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

To some extent, it has a lighter nose than the luscious

To some extent, it has a lighter nose than the luscious

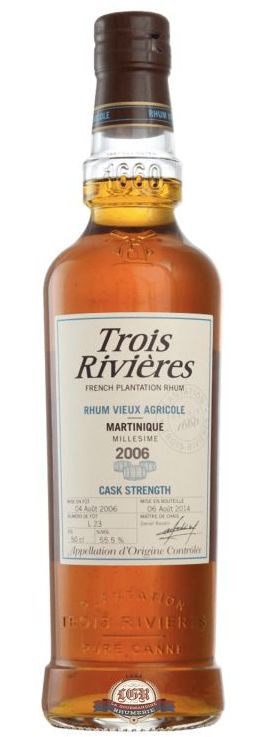

The Trois Rivières Brut de fût Millésime 2006 (which is its official name) is relatively unusual: it’s aged in new American oak barrels, not Limousin, and bottled at cask strength, not the more common 43-48%. And that gives it a solidity that elevates it somewhat over the standards we’ve become used to. Let’s start, as always, with the nose — it just becomes more assertive, and more clearly defined…although it seems somehow gentler (which is quite a neat trick when you think about it). It is redolent of caramel and vanilla first off, and then adds green apples, tart yoghurt, pears, white guavas, watermelon and papaya, and behind all that is a delectable series of herbs – rosemary, dill, even a hint of basil and aromatic pipe tobacco.

The Trois Rivières Brut de fût Millésime 2006 (which is its official name) is relatively unusual: it’s aged in new American oak barrels, not Limousin, and bottled at cask strength, not the more common 43-48%. And that gives it a solidity that elevates it somewhat over the standards we’ve become used to. Let’s start, as always, with the nose — it just becomes more assertive, and more clearly defined…although it seems somehow gentler (which is quite a neat trick when you think about it). It is redolent of caramel and vanilla first off, and then adds green apples, tart yoghurt, pears, white guavas, watermelon and papaya, and behind all that is a delectable series of herbs – rosemary, dill, even a hint of basil and aromatic pipe tobacco.

Okay so, on to palate. Straw yellow in the glass, it was softer and less intense, which, for a forty percenter, was both good and bad. Here the grassy and herbal notes took on more prominence, as did citrus, some tart unsweetened yoghurt, honey and cane juice. The youth was evident in the slight sharpness and lack of real roundness – the two years of ageing had

Okay so, on to palate. Straw yellow in the glass, it was softer and less intense, which, for a forty percenter, was both good and bad. Here the grassy and herbal notes took on more prominence, as did citrus, some tart unsweetened yoghurt, honey and cane juice. The youth was evident in the slight sharpness and lack of real roundness – the two years of ageing had  In 1923 La Mauny was sold to Théodore and Georges Bellonnie who enlarged and brought in new facilities such as a distillation column, new grinding mills and a steam engine. The distillery expanded hugely thanks to increased output and good marketing strategies and La Mauny rhums began to be exported around 1950. In 1970, after the Bellonnie brothers had both passed away, the Bordeaux traders and old-Martinique family of Bourdillon teamed up with Théodore Bellonnie’s widow and created the BBS Group. The company grew strongly, launching on the French market in 1977. Jean Pierre Bourdillon, who ran the new group, undertook to modernize La Mauny. He began by reorganizing the fields in order to make them accessible to mechanical harvesting and built a new distillery in 1984 (with a fourth mill, a three column still and a new boiler) a few hundred meters from the old one, increasing the cane crushing capacity and buying the equipment of the Saint James distillery in Acaiou, unused since 1958.

In 1923 La Mauny was sold to Théodore and Georges Bellonnie who enlarged and brought in new facilities such as a distillation column, new grinding mills and a steam engine. The distillery expanded hugely thanks to increased output and good marketing strategies and La Mauny rhums began to be exported around 1950. In 1970, after the Bellonnie brothers had both passed away, the Bordeaux traders and old-Martinique family of Bourdillon teamed up with Théodore Bellonnie’s widow and created the BBS Group. The company grew strongly, launching on the French market in 1977. Jean Pierre Bourdillon, who ran the new group, undertook to modernize La Mauny. He began by reorganizing the fields in order to make them accessible to mechanical harvesting and built a new distillery in 1984 (with a fourth mill, a three column still and a new boiler) a few hundred meters from the old one, increasing the cane crushing capacity and buying the equipment of the Saint James distillery in Acaiou, unused since 1958.

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The full and rather unwieldy title of the rum today is the Chantal Comte Rhum Agricole 1975 Extra Vieux de la Plantation de la Montagne Pelée, but let that not dissuade you. Consider it a column-still, cane-juice rhum aged around eight years, sourced from Depaz when it was still André Depaz’s property and the man was – astoundingly enough in today’s market – having real difficulty selling his aged stock. Ms. Comte, who was born in Morocco but had strong Martinique familial connections, had interned in the wine world, and was also mentored by Depaz and Paul Hayot (of Clement) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Martinique was suffering from overstock and poor sales.. And having access at low cost to such ignored and unknown stocks allowed her to really pick some amazing rums, of this is one.

The full and rather unwieldy title of the rum today is the Chantal Comte Rhum Agricole 1975 Extra Vieux de la Plantation de la Montagne Pelée, but let that not dissuade you. Consider it a column-still, cane-juice rhum aged around eight years, sourced from Depaz when it was still André Depaz’s property and the man was – astoundingly enough in today’s market – having real difficulty selling his aged stock. Ms. Comte, who was born in Morocco but had strong Martinique familial connections, had interned in the wine world, and was also mentored by Depaz and Paul Hayot (of Clement) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Martinique was suffering from overstock and poor sales.. And having access at low cost to such ignored and unknown stocks allowed her to really pick some amazing rums, of this is one.

Ah but when sipped, all that changes, and the clodhoppers go away and it dons a pair of ballet slippers. It’s stunningly fragrant, not quite delicate – that ballerina does have an extra pound or two – very firm and robust in flavour profile. Just on the first sip you can taste flowers, pears, papaya, honey, vanilla, raisins, grapes, all pulled together with a delectable light and salty note. There are nice citrus hints, a tease from the oak, ginger and cinnamon, and overall, it sips as nicely as it mixes. The finish is well handled, though content to play it safe – things are beginning to quieten down here, and it fades quietly without stomping on you – and certainly nothing new or original comes into being; the rhum is content to follow where the nose and palate led – fruits, pineapple, spices, ginger, vanilla – without breaking any new ground.

Ah but when sipped, all that changes, and the clodhoppers go away and it dons a pair of ballet slippers. It’s stunningly fragrant, not quite delicate – that ballerina does have an extra pound or two – very firm and robust in flavour profile. Just on the first sip you can taste flowers, pears, papaya, honey, vanilla, raisins, grapes, all pulled together with a delectable light and salty note. There are nice citrus hints, a tease from the oak, ginger and cinnamon, and overall, it sips as nicely as it mixes. The finish is well handled, though content to play it safe – things are beginning to quieten down here, and it fades quietly without stomping on you – and certainly nothing new or original comes into being; the rhum is content to follow where the nose and palate led – fruits, pineapple, spices, ginger, vanilla – without breaking any new ground.

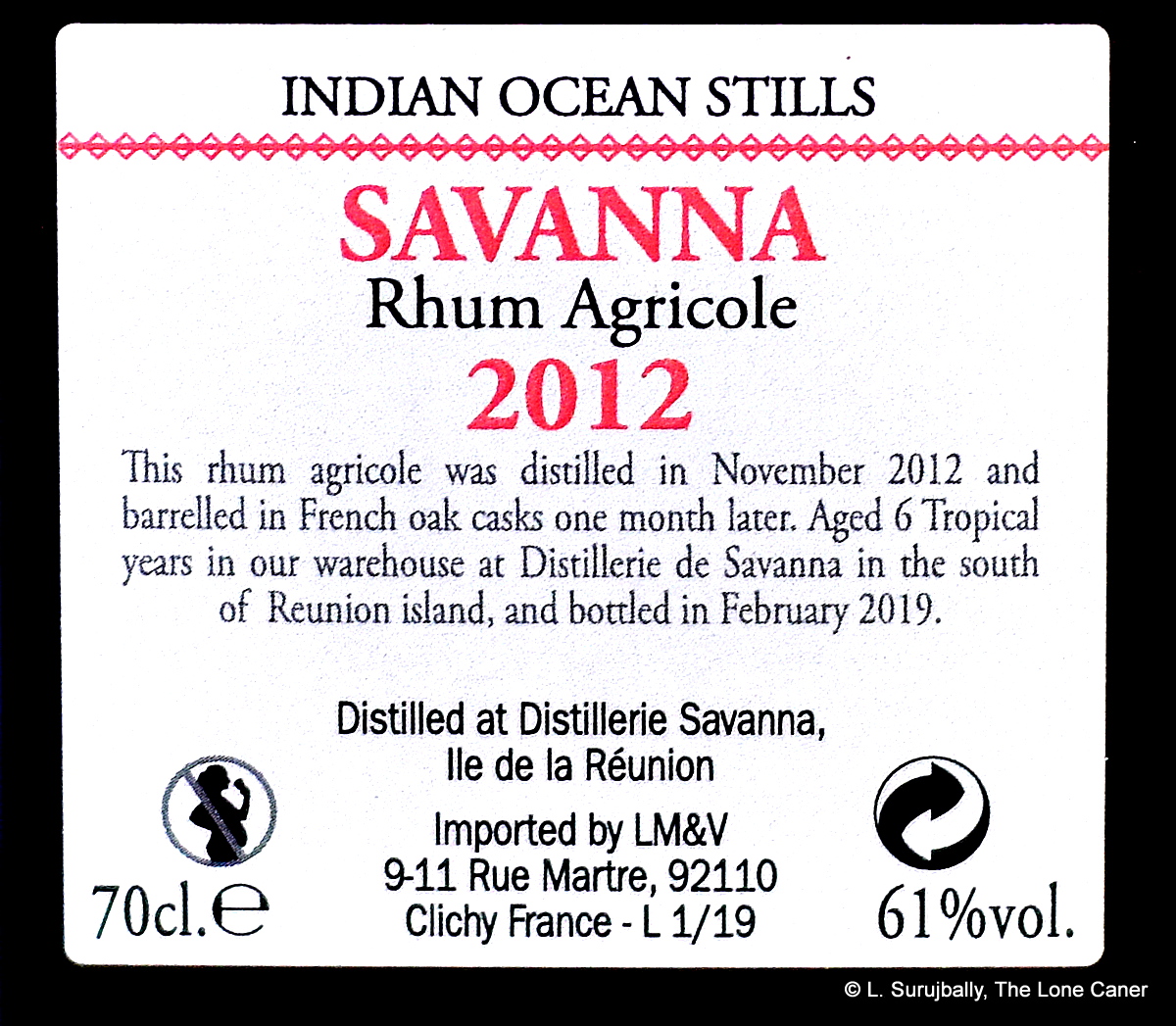

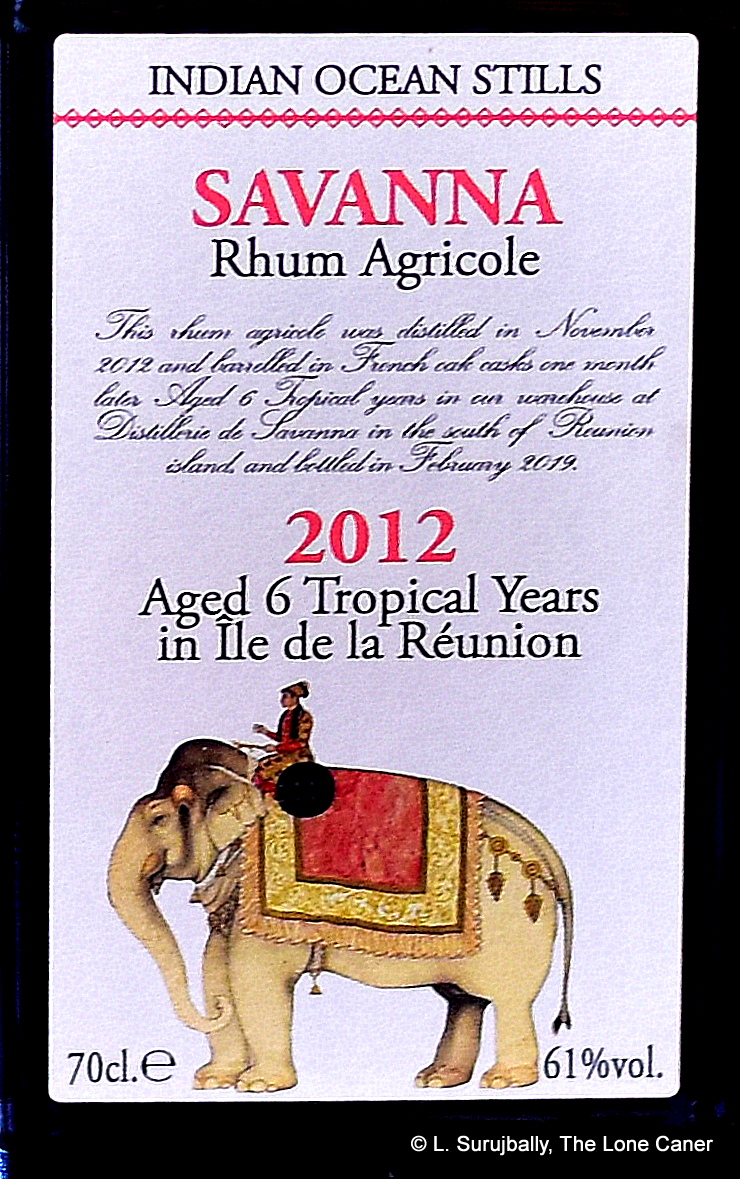

The “Indian Ocean Still” series of rums have a labelling concept somewhat different from the stark wealth of detail that usually accompanies a Velier collaboration. Personally, I find it very attractive from an artistic point of view – I love the man riding on the elephant motif of this and the companion

The “Indian Ocean Still” series of rums have a labelling concept somewhat different from the stark wealth of detail that usually accompanies a Velier collaboration. Personally, I find it very attractive from an artistic point of view – I love the man riding on the elephant motif of this and the companion  Man, this was a really good dram. It adhered to most of the tasting points of a true agricole — grassiness, crisp herbs, citrus, that kind of thing — without being slavish about it. It took a sideways turn here or there that made it quite distinct from most other agricoles I’ve tried. If I had to classify it, I’d say it was like a cross between the fruity silkiness of a St. James and the salt-oily notes of a Neisson.

Man, this was a really good dram. It adhered to most of the tasting points of a true agricole — grassiness, crisp herbs, citrus, that kind of thing — without being slavish about it. It took a sideways turn here or there that made it quite distinct from most other agricoles I’ve tried. If I had to classify it, I’d say it was like a cross between the fruity silkiness of a St. James and the salt-oily notes of a Neisson. Rumaniacs Review #105 | 0678

Rumaniacs Review #105 | 0678 Nose – A combination of the

Nose – A combination of the  Rumaniacs Review #104 | 0677

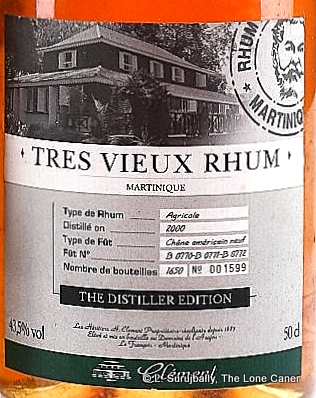

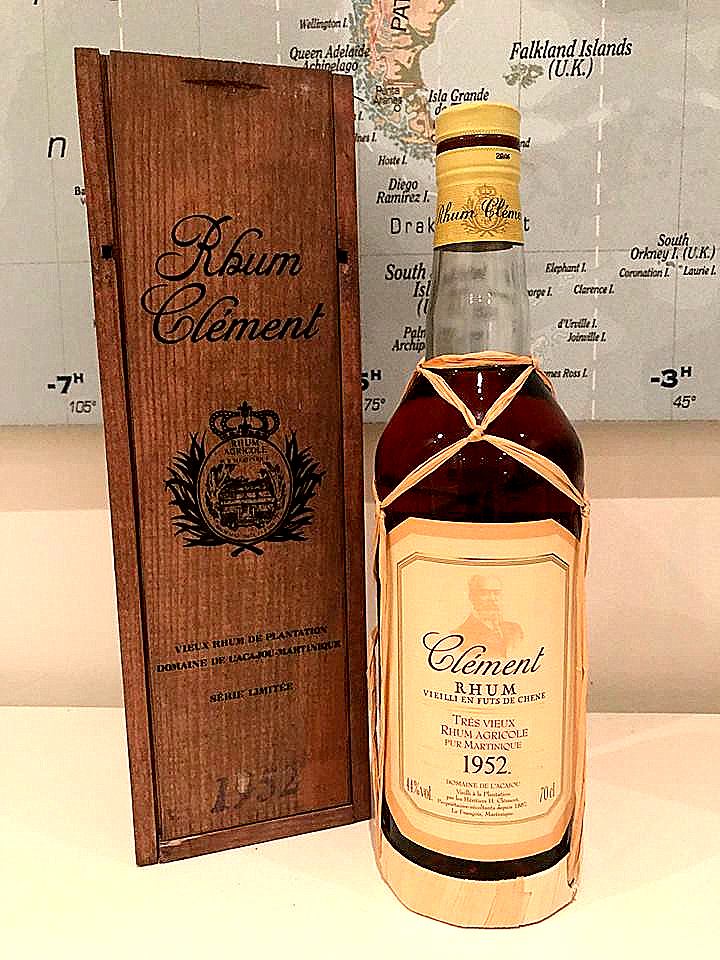

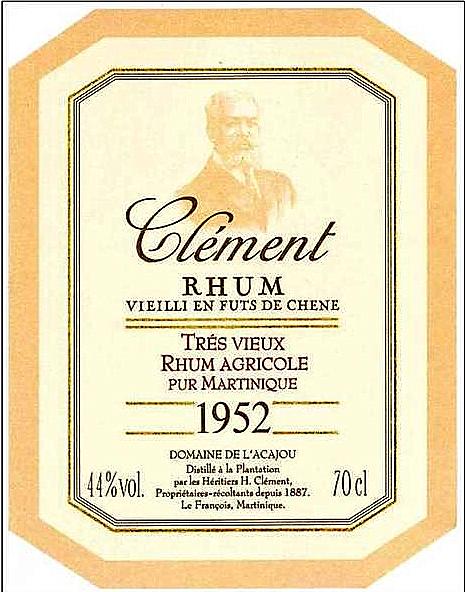

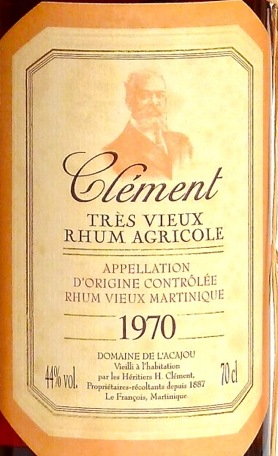

Rumaniacs Review #104 | 0677 Another peculiarity of the rhum is the “AOC” on the label. Since the AOC came into effect only in 1996, and even at its oldest this rhum was done ageing in 1991, how did that happen? Cyril told me it had been validated by the AOC after it was finalized, which makes sense (and probably applies to the 1976 edition as well), but then, was there a pre-1996 edition with one label and a post-1996 edition with another one? (the two different boxes it comes in suggests the possibility). Or, was the entire 1970 vintage aged to 1991, then held in inert containers (or bottled) and left to gather dust for some reason? Is either 1991 or 1985 even real? — after all, it’s entirely possible that the trio (of 1976, 1970 and 1952, whose labels are all alike) was released as a special millesime series in the late 1990s / early 2000s. Which brings us back to the original question – how old is the rhum?

Another peculiarity of the rhum is the “AOC” on the label. Since the AOC came into effect only in 1996, and even at its oldest this rhum was done ageing in 1991, how did that happen? Cyril told me it had been validated by the AOC after it was finalized, which makes sense (and probably applies to the 1976 edition as well), but then, was there a pre-1996 edition with one label and a post-1996 edition with another one? (the two different boxes it comes in suggests the possibility). Or, was the entire 1970 vintage aged to 1991, then held in inert containers (or bottled) and left to gather dust for some reason? Is either 1991 or 1985 even real? — after all, it’s entirely possible that the trio (of 1976, 1970 and 1952, whose labels are all alike) was released as a special millesime series in the late 1990s / early 2000s. Which brings us back to the original question – how old is the rhum?