“Pungent f*cker, isn’t it?” smirked Gregers, responding to my own incredulous text to him, when I recovered my glottis from the floor where the TECA had deposited and then stomped it flat. Another comment I got was from P-O Côté after the Vale Royal review came out: “Can’t wait to read your thoughts about the TECA…!! … Hard to describe without sounding gross.” And Rumboom remarked on a taste of “sweat” and “organic waste” in their own rundown of the TECA, with another post elsewhere actually using the word “manure.”

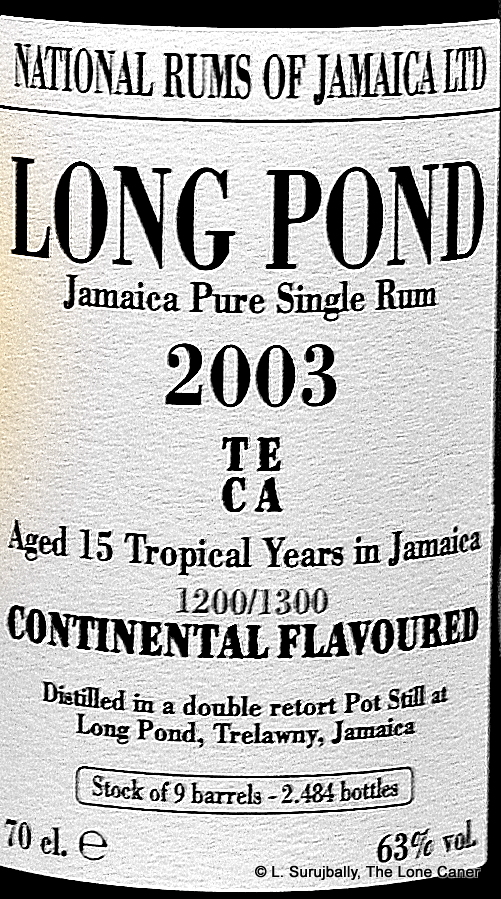

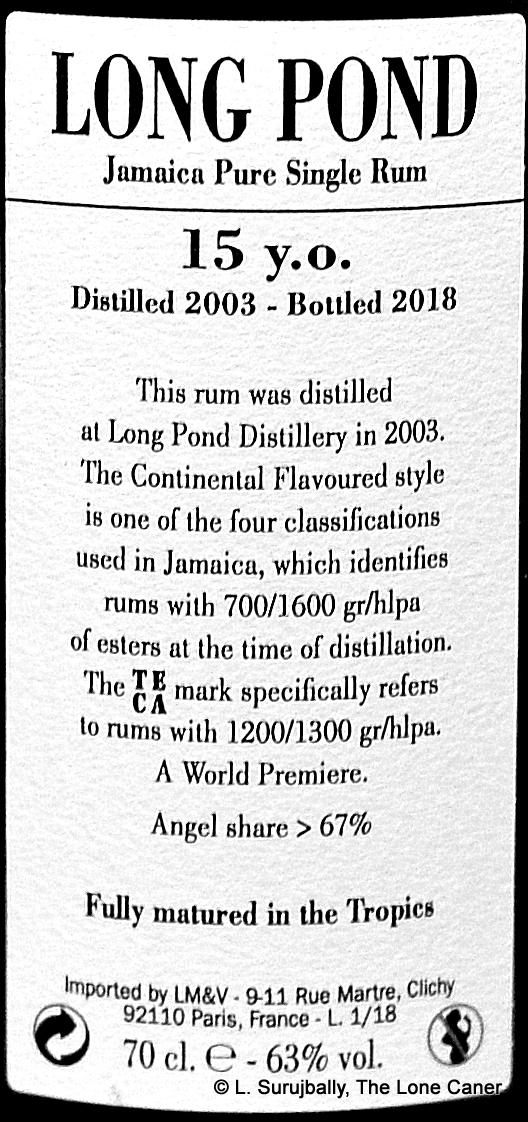

I start with these varied comments to emphasize that I am not alone in believing that the TECA is a rum you hold in your trembling hands when surveying the reeking battlefield of the zombie apocalypse. I’m a fairly fit old fart of some mental fortitude, I’ve tasted rums from up and down the quality ladder…but the TECA still left me shell-shocked and shaking, and somewhere I could hear Luca sniggering happily and doing a fist pump. Partly or completely, this was because of the huge ester level the rum displayed -1200 gr/hlpaa (remember, 1600 is the maximum legal limit after which we enter “easily-weaponizable” territory), which the makers, staying within the traditional ester band names, refer to as “Continental Flavoured” but which I just call shattering.

In sampling the initial nose of the third rum in the NRJ series, I am not kidding you when I say that I almost fell out of my chair in disbelief. The aroma was the single most rancid, hogo-laden ester bomb I’d ever experienced – I’ve tasted hundreds of rums in my time, but never anything remotely like this (except perhaps the Japanese Seven Seas rum, and I’d thought that one was a contaminated sample; now, I’m not so sure). All of the hinted-at off-the-wall aromas of the Cambridge were present here, except they were gleefully torqued up – a lot. It smelled like the aforementioned tannery gone amok or the hair salon dumping every chemical on the floor (at once) – it was a massive blurt of sulphur, methane, rubber and plastic dissolving in a bubbling pool of ammonia. It smelled like hemp rope and decomposing wet jute bags, joined by something really rancid – rotting meat, microwaved fish, and three-day-old roadkill marinating on a hot day next to the asphalt machine. There was the scent of a strong soy-flavoured vegetable soup and spoiling chicken tikka, raw onions and sweat. The clear, fruity ester background was so intense it made the eyes water and the nose pucker, cold and clear and precise, giving rather less enjoyment than a furious bitch slap of sharp pineapples, gooseberries, ginnips, unripe mangoes, salmiak, green apples. I know this sounds like a lot, but the rum’s nose went so far into uncharted territory that I really spent a long time on it, and this is what was there. And at the end, I really couldn’t say I enjoyed it – it was just too much, of everything. Hogo is what this kind of rotten meat flavour is called – or rancio or dunder or whatever — but for my money, it stands for “Ho God!!”

In sampling the initial nose of the third rum in the NRJ series, I am not kidding you when I say that I almost fell out of my chair in disbelief. The aroma was the single most rancid, hogo-laden ester bomb I’d ever experienced – I’ve tasted hundreds of rums in my time, but never anything remotely like this (except perhaps the Japanese Seven Seas rum, and I’d thought that one was a contaminated sample; now, I’m not so sure). All of the hinted-at off-the-wall aromas of the Cambridge were present here, except they were gleefully torqued up – a lot. It smelled like the aforementioned tannery gone amok or the hair salon dumping every chemical on the floor (at once) – it was a massive blurt of sulphur, methane, rubber and plastic dissolving in a bubbling pool of ammonia. It smelled like hemp rope and decomposing wet jute bags, joined by something really rancid – rotting meat, microwaved fish, and three-day-old roadkill marinating on a hot day next to the asphalt machine. There was the scent of a strong soy-flavoured vegetable soup and spoiling chicken tikka, raw onions and sweat. The clear, fruity ester background was so intense it made the eyes water and the nose pucker, cold and clear and precise, giving rather less enjoyment than a furious bitch slap of sharp pineapples, gooseberries, ginnips, unripe mangoes, salmiak, green apples. I know this sounds like a lot, but the rum’s nose went so far into uncharted territory that I really spent a long time on it, and this is what was there. And at the end, I really couldn’t say I enjoyed it – it was just too much, of everything. Hogo is what this kind of rotten meat flavour is called – or rancio or dunder or whatever — but for my money, it stands for “Ho God!!”

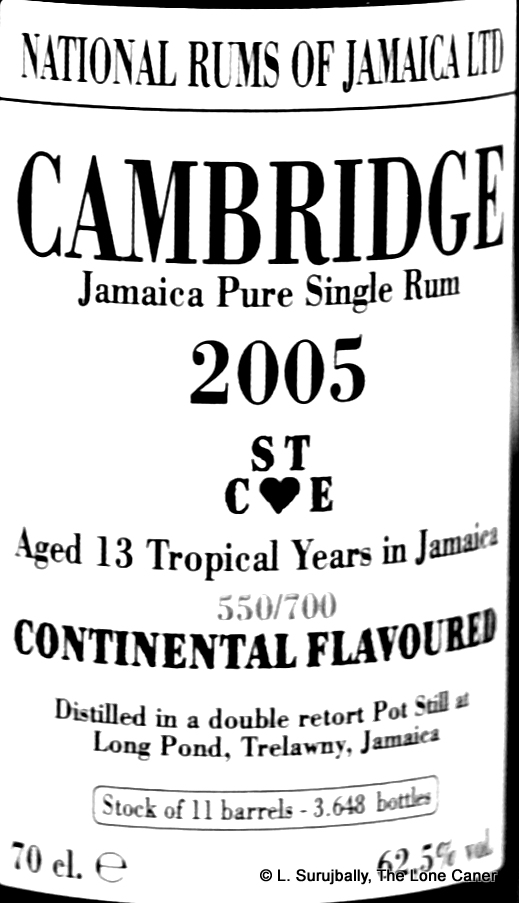

So that’s bad, right? Reading this, you’d think so. But courage, Sir Knight, hoist up thy codpiece and taste it. The very first expression in that section of my notes is a disbelieving “WTF?” … because it simply dumbfounded me – where did all the crazy-ass crap go? It tasted of soda pop – coke, or fanta – persimmons and passion fruits and red currants, sharp and tasty. Salt, brine, bags of olives, plastic, rubber, vanilla, licorice all rubbed shoulders in a melange made pleasant just by comparing it to the trauma of what went before. The rancio and spoiling meat hogo retreated so fast it’s like they just vapourized themselves. The flavours were powerful and intense, yes – at 62.5% ABV they could hardly be anything else – and you got much of the same fruitiness that lurked behind the funk of the smells, mangoes, tart gooseberries, red currants, unsweetened yoghurt and sour cream. But the real take away was that the nose and palate diverged so much. Aside from the sharp fruits and receding vegetable soup, there was also pistachio nuts, a sort of woodsy cologne, and even some over-sugared soda pop. And when I hit the finish line, it exhaled with a long sigh redolent of more pistachios, vanilla, anise, soy, olives and a veritable orchard of rotting fruits and banana skins.

The Long Pond TECA rum from National Rums of Jamaica is a grinning ode to excess of every kind. Given the profile I describe above (especially how it smelled) I think it took real courage for Luca to release it, and it once again demonstrates that he’s willing to forego initial sales to show us something we have not seen before, point us in a direction at odds with prevailing trends. It’s certainly unique – Luca remarked to me that it was probably the first time anyone had ever released such a high-ester well-aged Long Pond, and I agree. So far we’ve seen that the low-level-ester Vale Royal was a lovely, near-traditional Jamaican rum that edged gently away from more familiar island profiles, and the mid-level-ester Cambridge dared to step over the line and become something remarkably different, with strong tastes that almost redefined Jamaican and provided a taste profile that was breathtaking – if not entirely something I cared for. But the TECA didn’t edge towards the line, it didn’t step over it – it was a rum that blasted way beyond and became something that knocked me straight into next week. This was and will remain one of the most original, pungently unbelievable, divisive rums I’ve tried in my entire writing career, because, quite frankly, I believe it’s a rum which few outside the deep-dive rum-junkies of the Jamaican style will ever like. And love? Well, who knows. It may yet grow on me.

(#565)(79/100)

Background notes

(With the exception of the estate section, all remarks here are the same for the four reviews)

This series of essays on the four NRJ rums contains:

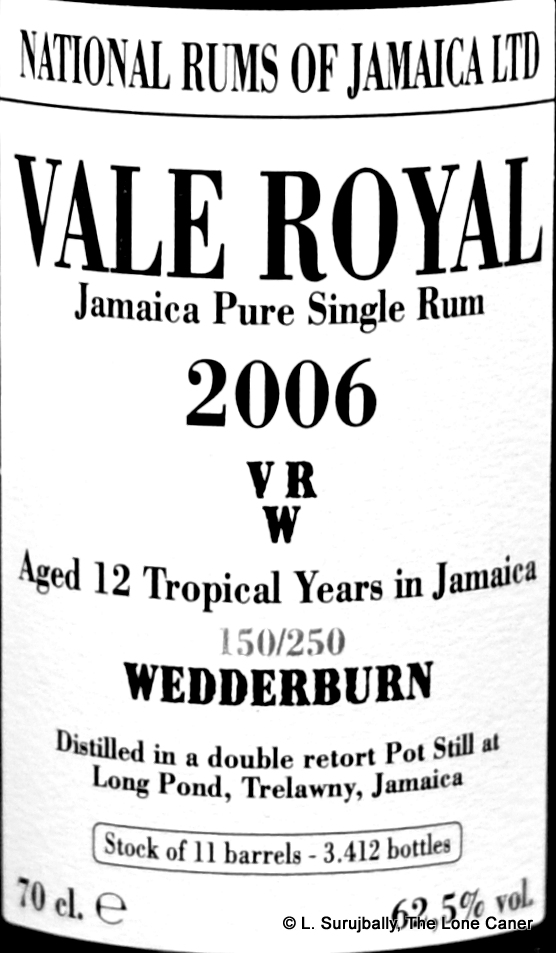

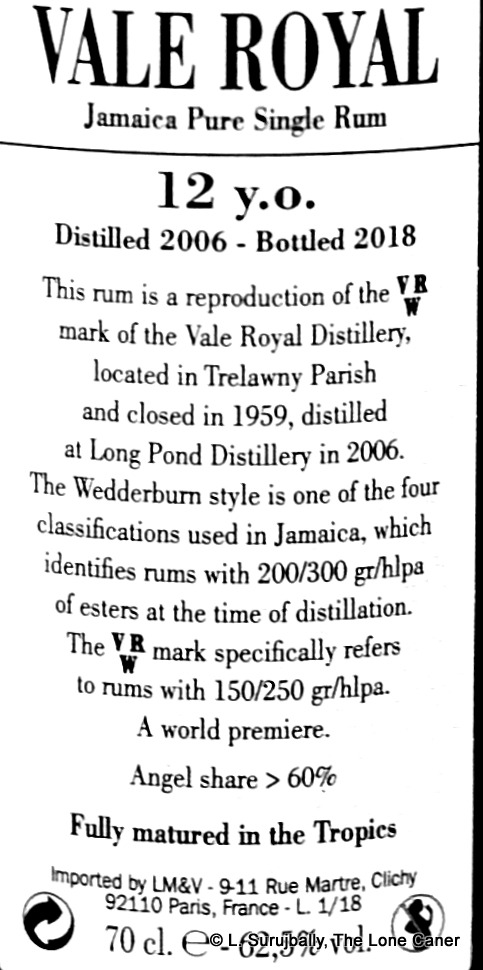

- NRJ Vale Royal 2006 12 YO VRW (11 barrels, 3412 bottles) 150/250 esters level

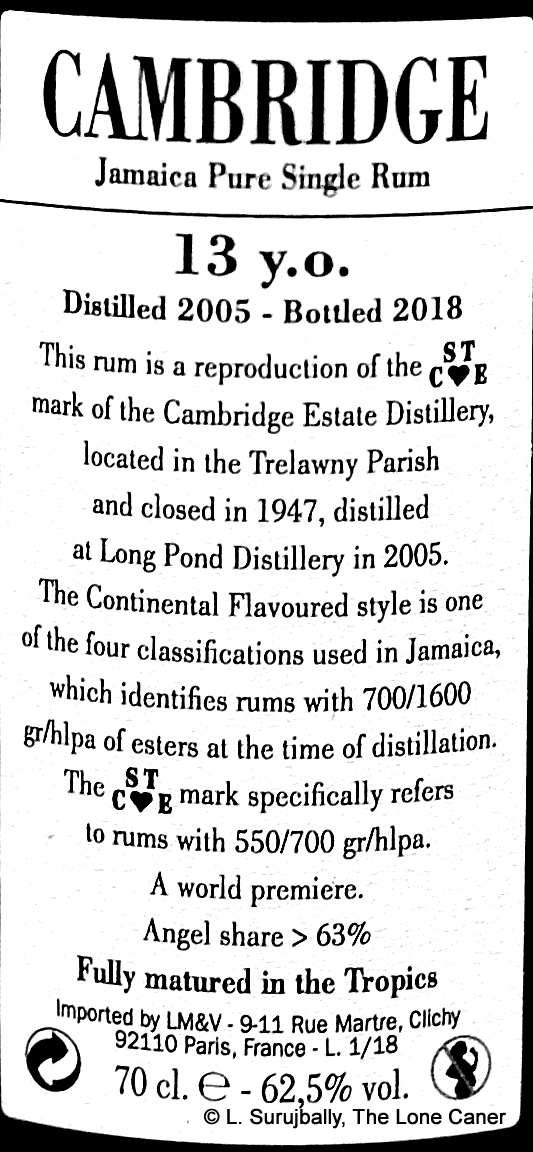

- NRJ Cambridge 2005 13 YO STC❤E (11 barrels, 3648 bottles) 550/700 esters level

- NRJ Long Pond 2003 15 YO TECA (9 barrels, 2484 bottles) 1200/1300 esters level

- NRJ Long Pond 2007 11 YO TECC (11 barrels, 3325 bottles), 1500/1700 esters level + summary

In brief, these are all rums from Long Pond distillery, and represent distillates with varying levels of esters (I have elected to go in the direction of lowest ester count → highest, in these reviews). Much of the background has been covered already by two people: the Cocktail Wonk himself with his Jamaican estate profiles and related writings, and the first guy through the gate on the four rums, Flo Redbeard of Barrel Aged Thoughts, who has written extensively on them all (in German) in October 2018. As a bonus, note that a bunch of guys sampled and briefly reviewed all four on Rumboom (again, in German) the same week as my own reviews came out, for those who want some comparisons.

In brief, these are all rums from Long Pond distillery, and represent distillates with varying levels of esters (I have elected to go in the direction of lowest ester count → highest, in these reviews). Much of the background has been covered already by two people: the Cocktail Wonk himself with his Jamaican estate profiles and related writings, and the first guy through the gate on the four rums, Flo Redbeard of Barrel Aged Thoughts, who has written extensively on them all (in German) in October 2018. As a bonus, note that a bunch of guys sampled and briefly reviewed all four on Rumboom (again, in German) the same week as my own reviews came out, for those who want some comparisons.

The various Jamaican ester marks

These are definitions of ester counts, and while most rums issued in the last ten years make no mention of such statistics, it seems to be a coming thing based on its increasing visibility in marketing and labelling: right now most of this comes from Jamaica, but Reunion’s Savanna also has started mentioning it in its Grand Arôme line of rums. For those who are coming into this subject cold, esters are the chemical compounds responsible for much of a given rum’s flowery and fruity flavours – they are measured in grams per hectoliter of pure alcohol, a hectoliter being 100 liters; a light Cuban style rum can have as little as 20 g/hlpa while an ester gorilla like the DOK can go right up to the legal max of 1600 at which point it’s no longer much of a drinker’s rum, but a flavouring agent for lesser rums. (For good background reading, check out the Wonk’s work on Jamaican funk, here).

Back in the day, the British classified Jamaican rums into four major styles, and many estates took this a few steps further by subdividing the major categories even more:

Standard Classification

- Common Clean 50-150 gr/hlpa

- Plummer 150-200 gr/hlpa

- Wedderburn 200-300 gr/hlpa

- Continental Flavoured 700-1600 gr/hlpa

Exactly who came up with the naming nomenclature, or what those names mean, is something of a historian’s dilemma, and what they call the juice between 301 to 699 gr/hlpa is not noted, but if anyone knows more, drop me a line and I’ll add the info. Note in particular that these counts reflect the esters after distillation but before ageing, so a chemical test might find a differing value if checked after many years’ rest in a barrel.

Long Pond itself sliced and diced and came up with their own ester subdivisions, and the inference seems to be that the initials probably refer to distilleries and estates acquired over the decades, if not centuries. It would also appear that the ester counts on the four bottles do indeed reflect Long Pond’s system, not the standard notation (tables.

RV 0-20

CQV 20-50

LRM 50-90

ITP /LSO 90-120

HJC / LIB 120-150

IRW / VRW 150-250

HHH / OCLP 250-400

LPS 400-550

STC❤E 550-700

TECA 1200-1300

TECB 1300-1400

TECC 1500-1600

The Estate Name:

It’s unclear whether the TECA stands for Tilston Estate, one of the estates that got subsumed into Long Pond in the wave of consolidations in the 1940s and 1950s (this is the theory to which Luca subscribes), or for Trelawny Estates, the umbrella company created in the 1950s before being taken over by the Government and renamed National Rums of Jamaica. This is where some additional research is needed – nobody has written (so far) on the meaning of the “CA”, though given the Long Pond marks listed above, it’s reasonable to suppose it’s Tilston/Trelawny Estate, Continental Type A (as opposed to “B” or “C” with progressively higher ester levels. The various histories of Long Pond written by Barrel Aged Thoughts, the Cocktail Wonk and DuRhum provide useful background reading, though they do not settle the mark designation issue conclusively one way or the other.

Note: National Rums of Jamaica is not an estate or a distillery in and of itself, but is an umbrella company owned by three organizations: the Jamaican Government, Maison Ferrand of France (who got their stake in 2017 when they bought WIRD in Barbados, the original holder of the share Ferrand now hold) and Guyana’s DDL.

There’s a reason for that. What these esters do is provide a varied and intense and enormously boosted flavour profile, not all of which can be considered palatable at all times, though the fruitiness and light flowers are common to all of them and account for much of the popularity of such rums which masochistically reach for higher numbers, perhaps just to say “I got more than you, buddy”. Maybe, but some caution should be exercised too, because high levels of esters do not in and of themselves make for really good rums every single time. Still, with Luca having his nose in the series, one can’t help but hope for something amazingly new and perhaps even spectacular. I sure wanted that myself.

There’s a reason for that. What these esters do is provide a varied and intense and enormously boosted flavour profile, not all of which can be considered palatable at all times, though the fruitiness and light flowers are common to all of them and account for much of the popularity of such rums which masochistically reach for higher numbers, perhaps just to say “I got more than you, buddy”. Maybe, but some caution should be exercised too, because high levels of esters do not in and of themselves make for really good rums every single time. Still, with Luca having his nose in the series, one can’t help but hope for something amazingly new and perhaps even spectacular. I sure wanted that myself. These are definitions of ester counts, and while most rums issued in the last ten years make no mention of such statistics, it seems to be a coming thing based on its increasing visibility in marketing and labelling: right now most of this comes from Jamaica, but Reunion’s Savanna also has started mentioning it in its Grand Arôme line of rums. For those who are coming into this subject cold, esters are the chemical compounds responsible for much of a given rum’s flowery and fruity flavours – they are measured in grams per hectoliter of pure alcohol, a hectoliter being 100 liters; a light Cuban style rum can have as little as 20 g/hlpa while an ester gorilla like the DOK can go right up to the legal max of 1600 at which point it’s no longer much of a drinker’s rum, but a flavouring agent for lesser rums. (For good background reading, check out the

These are definitions of ester counts, and while most rums issued in the last ten years make no mention of such statistics, it seems to be a coming thing based on its increasing visibility in marketing and labelling: right now most of this comes from Jamaica, but Reunion’s Savanna also has started mentioning it in its Grand Arôme line of rums. For those who are coming into this subject cold, esters are the chemical compounds responsible for much of a given rum’s flowery and fruity flavours – they are measured in grams per hectoliter of pure alcohol, a hectoliter being 100 liters; a light Cuban style rum can have as little as 20 g/hlpa while an ester gorilla like the DOK can go right up to the legal max of 1600 at which point it’s no longer much of a drinker’s rum, but a flavouring agent for lesser rums. (For good background reading, check out the

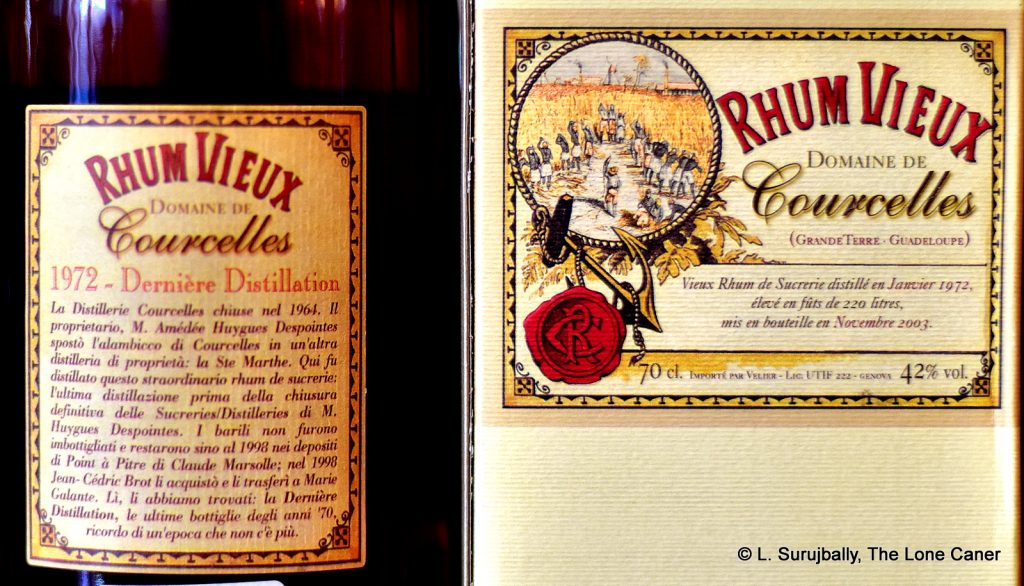

Consider first the nose. Frankly, I thought it was lovely – not just because it was different (it certainly was), but because it combined the familiar and the strange in intriguing new ways. It started off dusty, musky, loamy, earthy…the sort of damp potting soil in which my wife exercises her green thumb. There was also a bit of vaguely herbal funk going on in the background, dry, like a hemp rope, or an old jute sack that once held rice paddy. But all this was background because on top of all that was the fruitiness, the flowery notes which gave the rum its character – cherries, peaches, pineapples, mixed with salt caramel, vanilla, almonds, hazelnuts and flambeed bananas. I mean, that was a really nice series of aromas.

Consider first the nose. Frankly, I thought it was lovely – not just because it was different (it certainly was), but because it combined the familiar and the strange in intriguing new ways. It started off dusty, musky, loamy, earthy…the sort of damp potting soil in which my wife exercises her green thumb. There was also a bit of vaguely herbal funk going on in the background, dry, like a hemp rope, or an old jute sack that once held rice paddy. But all this was background because on top of all that was the fruitiness, the flowery notes which gave the rum its character – cherries, peaches, pineapples, mixed with salt caramel, vanilla, almonds, hazelnuts and flambeed bananas. I mean, that was a really nice series of aromas. The various Jamaican ester marks

The various Jamaican ester marks

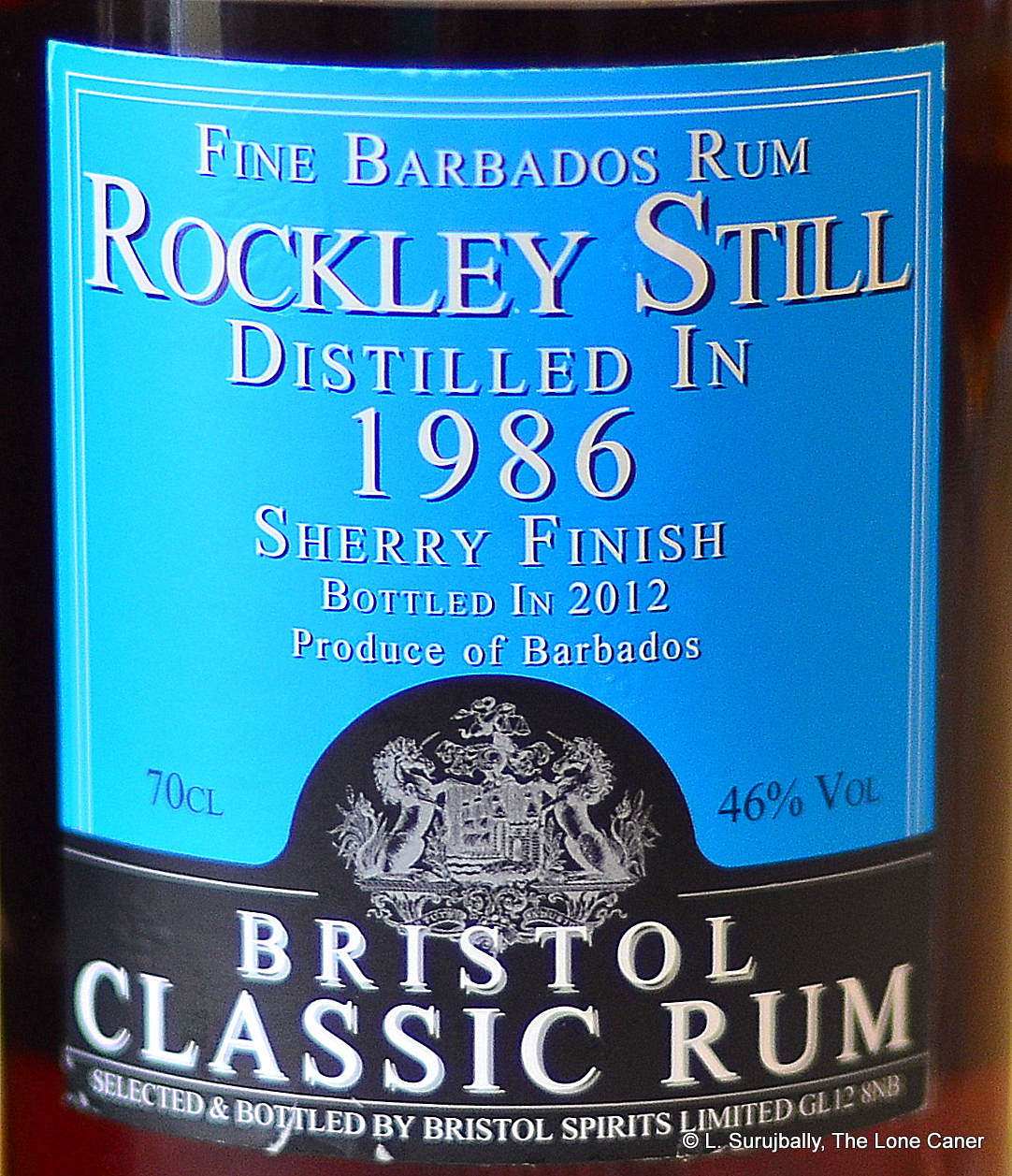

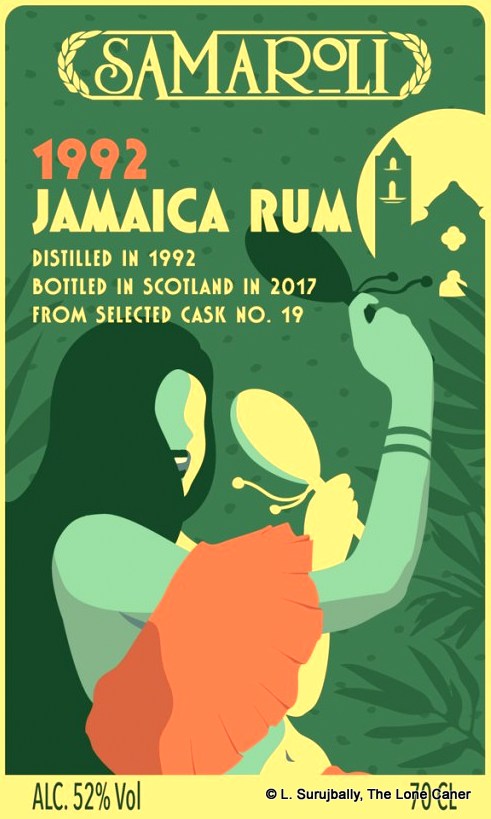

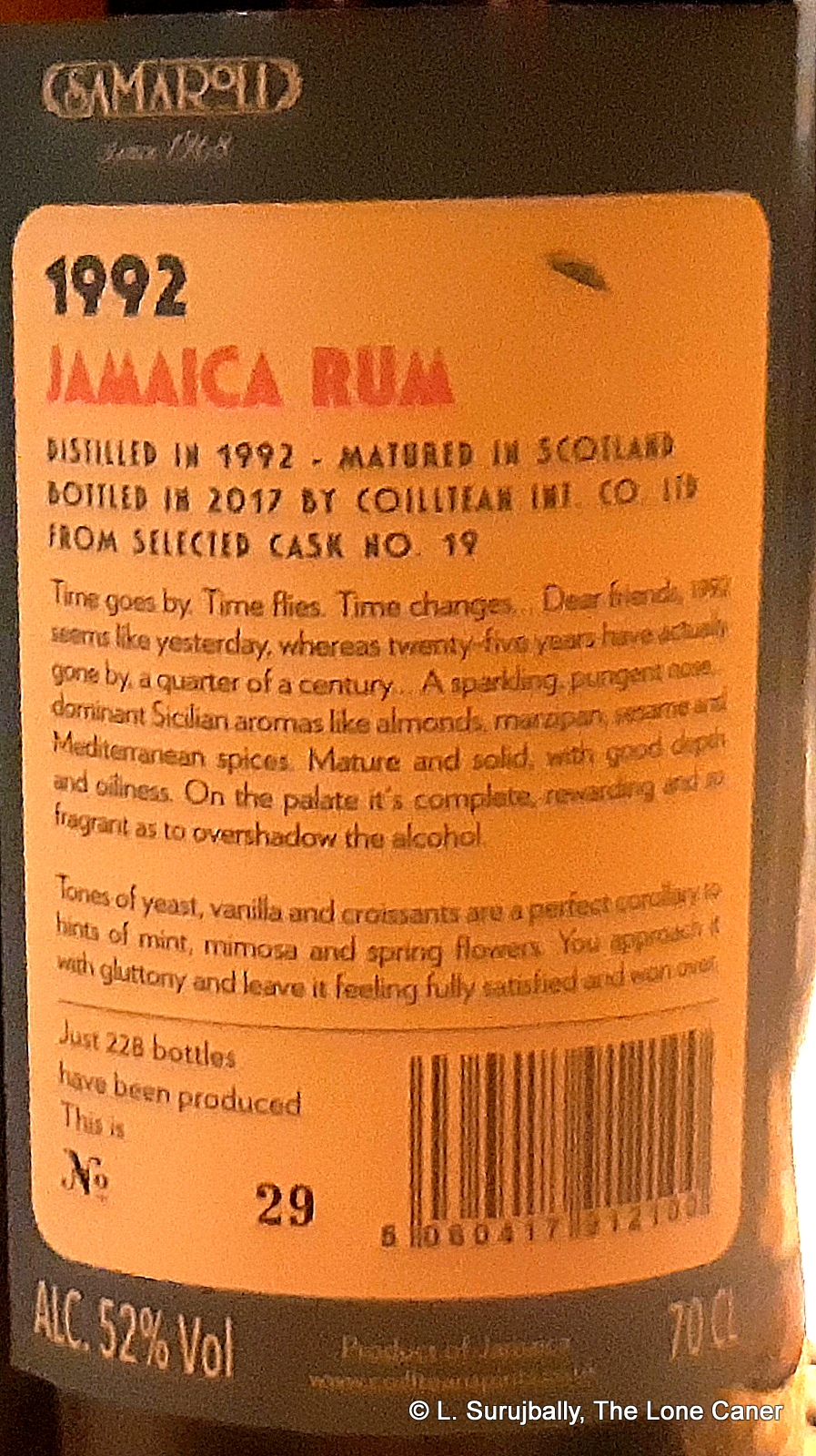

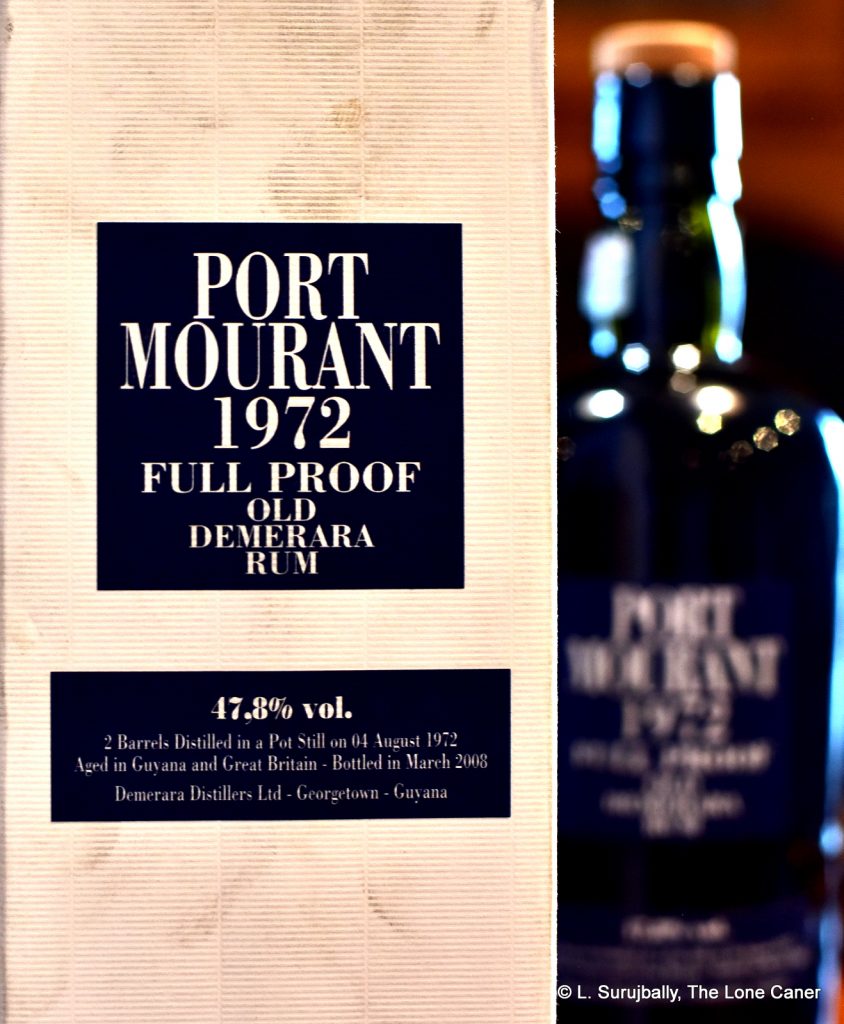

The brief technical blah is as follows: bottled by Bristol Spirits out of the UK from distillate left to age in Scotland for 26 years; a pot still product (I refer you to

The brief technical blah is as follows: bottled by Bristol Spirits out of the UK from distillate left to age in Scotland for 26 years; a pot still product (I refer you to

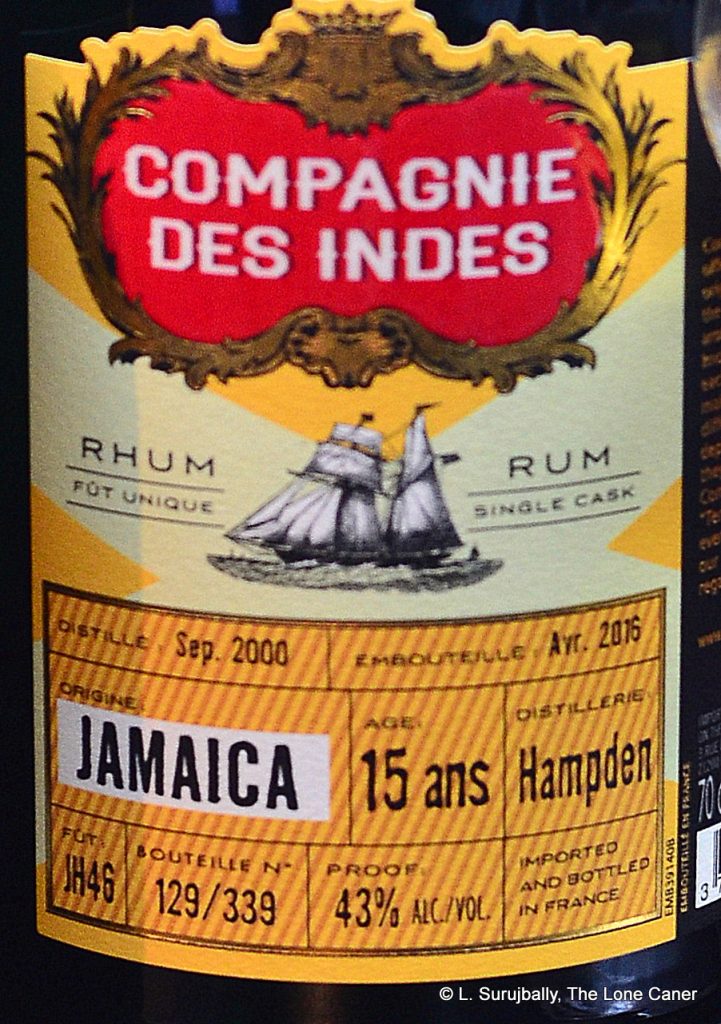

So, given how many Jamaicans are on the scene these days, how does this young, continentally aged 55.9% golden rum fare? Not too shabbily. It’s strong but very approachable, even on the nose, which doesn’t waste any time getting started but announces its ester-rich aromas immediately and with authority: acetone, nail polish and some rubber plus a smell of righteous funk (spoiling fruits, rotten bananas, that kind of thing). Its relative youth is apparent in the uncouth sharpness of the initial aromas, but once one sticks with it, it settles into its own special groove, calms itself down and does a neat little balancing act between sharper scents of citrus, cider, apples, hard yellow mangoes and green grapes, and softer ones of bananas, cumin, vanilla, marshmallows and cloves.

So, given how many Jamaicans are on the scene these days, how does this young, continentally aged 55.9% golden rum fare? Not too shabbily. It’s strong but very approachable, even on the nose, which doesn’t waste any time getting started but announces its ester-rich aromas immediately and with authority: acetone, nail polish and some rubber plus a smell of righteous funk (spoiling fruits, rotten bananas, that kind of thing). Its relative youth is apparent in the uncouth sharpness of the initial aromas, but once one sticks with it, it settles into its own special groove, calms itself down and does a neat little balancing act between sharper scents of citrus, cider, apples, hard yellow mangoes and green grapes, and softer ones of bananas, cumin, vanilla, marshmallows and cloves.

And the taste, the palate, the way it comes together, it’s masterful. At 52% it’s downright near damned perfect – the the balance between mouth puckering citrus plus laid back funk, and easier, softer flavours is unbelievably well done. Soda pop, honey, cereal, red currants, raspberries, fanta and orange zest dance exuberantly cross the tongue, never faltering, never allowing any one piece to dominate. Like an exquisitely choreographed dance number, the molasses, vanillas and fruits (peaches, yellow plums, pears, ripe yellow Thai mangoes) tango alongside sharper notes of citrus, lemon zest, overripe bananas, sandalwood and ginger. Even the finish is spectacular – just long enough, just sharp enough, just mellow enough, allowing each of the individually discerned flavours of fruits, toffee, chocolate and citrus to come out on stage one last time for a bow, before fading back and making way for the next one

And the taste, the palate, the way it comes together, it’s masterful. At 52% it’s downright near damned perfect – the the balance between mouth puckering citrus plus laid back funk, and easier, softer flavours is unbelievably well done. Soda pop, honey, cereal, red currants, raspberries, fanta and orange zest dance exuberantly cross the tongue, never faltering, never allowing any one piece to dominate. Like an exquisitely choreographed dance number, the molasses, vanillas and fruits (peaches, yellow plums, pears, ripe yellow Thai mangoes) tango alongside sharper notes of citrus, lemon zest, overripe bananas, sandalwood and ginger. Even the finish is spectacular – just long enough, just sharp enough, just mellow enough, allowing each of the individually discerned flavours of fruits, toffee, chocolate and citrus to come out on stage one last time for a bow, before fading back and making way for the next one I don’t know what they did differently in this rum from others they’ve issued for the last forty years, what selection criteria they used, but

I don’t know what they did differently in this rum from others they’ve issued for the last forty years, what selection criteria they used, but

On the palate, I didn’t think it could quite beat out the CdI Worthy Park (which was half its age, though quite a bit stronger); but it definitely had more force and more uniqueness in the way it developed than the Longpond and the Mezans. It started with cherries, going-off bananas mixed with a delicious citrus backbone, not too excessive. After ten minutes or so it opened further into a medium sweet set of fruits (peaches, pears, apples), and showed notes of oak, cinnamon, some brininess, green grapes, all backed up by delicate florals that were very aromatic and provided a good background for the finish. That in turn glided along to a relatively serene, slightly heated medium-long stop with just a few bounces on the road to its eventual disappearance, though with little more than what the palate had already demonstrated. Fruitiness and some citrus and cinnamon was about it.

On the palate, I didn’t think it could quite beat out the CdI Worthy Park (which was half its age, though quite a bit stronger); but it definitely had more force and more uniqueness in the way it developed than the Longpond and the Mezans. It started with cherries, going-off bananas mixed with a delicious citrus backbone, not too excessive. After ten minutes or so it opened further into a medium sweet set of fruits (peaches, pears, apples), and showed notes of oak, cinnamon, some brininess, green grapes, all backed up by delicate florals that were very aromatic and provided a good background for the finish. That in turn glided along to a relatively serene, slightly heated medium-long stop with just a few bounces on the road to its eventual disappearance, though with little more than what the palate had already demonstrated. Fruitiness and some citrus and cinnamon was about it.

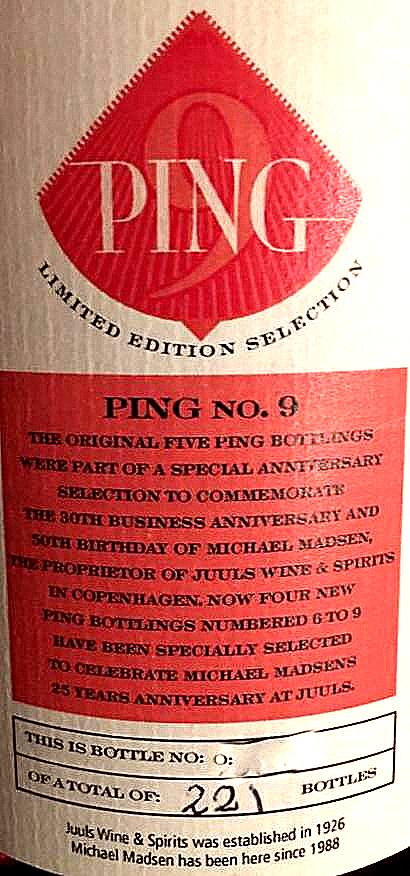

The nose rather interestingly presented hints of a funky kind of fruitiness at the beginning (like a low rent Jamaican, perhaps), while the characteristic clarity and crisp individualism of the aromas such as the other Nine Leaves rums possessed, remained. It was musky and sweet, had some zesty citrus notes, fresh apples, pears and overall had a pleasing clarity about it. Plus there were baking spices as well – nutmeg and cumin and those rounded out the profile quite well.

The nose rather interestingly presented hints of a funky kind of fruitiness at the beginning (like a low rent Jamaican, perhaps), while the characteristic clarity and crisp individualism of the aromas such as the other Nine Leaves rums possessed, remained. It was musky and sweet, had some zesty citrus notes, fresh apples, pears and overall had a pleasing clarity about it. Plus there were baking spices as well – nutmeg and cumin and those rounded out the profile quite well.

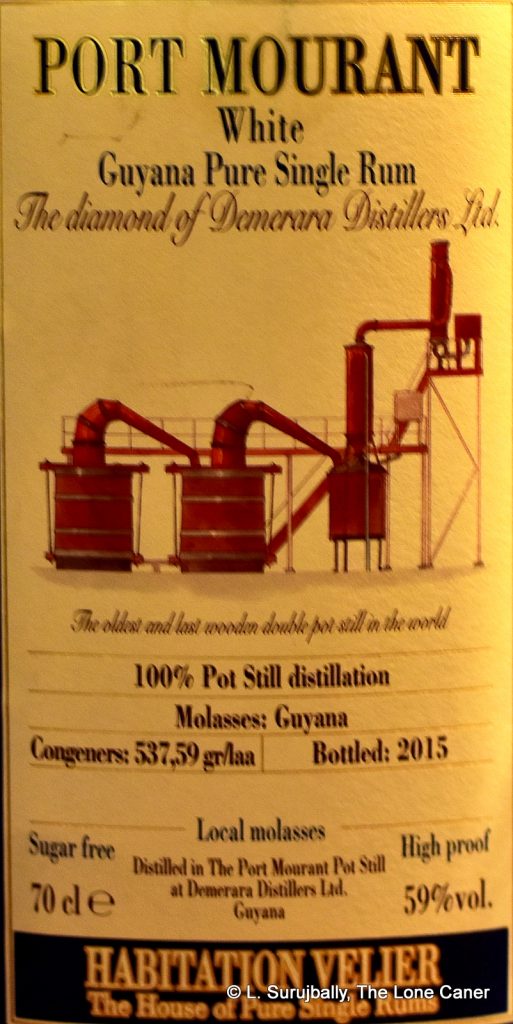

The nose made an immediate and emphatic response: “Here’s how.” I had exasperatedly grumbled

The nose made an immediate and emphatic response: “Here’s how.” I had exasperatedly grumbled

Unaged rums take some getting used to because they are raw from the barrel and therefore the rounding out and mellowing of the profile which ageing imparts, is not a factor. That means all the jagged edges, dirt, warts and everything, remain. Here that was evident after a single sip: it was sharp and fierce, with the licorice notes subsumed into dirtier flavours of salt beef, brine, olives and garlic pork (seriously!). It took some time for other aspects to come forward – gherkins, leather, flowers and varnish – and even then it was not until another half hour had elapsed that crisper acidic notes like unripe apples and thai lime leaves (I get those to buy in the local market), were noticeable. Plus some vanilla – where on earth did that come from? It all led to a long, duty, dry finish that provided yet more: sweet, sugary, sweet-and-salt soy sauce in a clear soup. Damn but this was a heady, complex piece of work. I liked it a lot, really.

Unaged rums take some getting used to because they are raw from the barrel and therefore the rounding out and mellowing of the profile which ageing imparts, is not a factor. That means all the jagged edges, dirt, warts and everything, remain. Here that was evident after a single sip: it was sharp and fierce, with the licorice notes subsumed into dirtier flavours of salt beef, brine, olives and garlic pork (seriously!). It took some time for other aspects to come forward – gherkins, leather, flowers and varnish – and even then it was not until another half hour had elapsed that crisper acidic notes like unripe apples and thai lime leaves (I get those to buy in the local market), were noticeable. Plus some vanilla – where on earth did that come from? It all led to a long, duty, dry finish that provided yet more: sweet, sugary, sweet-and-salt soy sauce in a clear soup. Damn but this was a heady, complex piece of work. I liked it a lot, really.

Say what you will about tropical ageing, there’s nothing wrong with a good long continental slumber when we get stuff like this out the other end. Again it presented as remarkably soft for the strength, allowing tastes of fruits, light licorice, vanilla, cherries, plums, and peaches to segue firmly across the tongue. Some sea salt, caramel, dates, plums, smoke and leather and a light dusting of cinnamon and florals provided additional complexity, and over all, it was really quite a good rum, closing the circle with a lovely long finish redolent of a fruit basket, port-infused cigarillos, flowers and a few extra spices.

Say what you will about tropical ageing, there’s nothing wrong with a good long continental slumber when we get stuff like this out the other end. Again it presented as remarkably soft for the strength, allowing tastes of fruits, light licorice, vanilla, cherries, plums, and peaches to segue firmly across the tongue. Some sea salt, caramel, dates, plums, smoke and leather and a light dusting of cinnamon and florals provided additional complexity, and over all, it was really quite a good rum, closing the circle with a lovely long finish redolent of a fruit basket, port-infused cigarillos, flowers and a few extra spices.

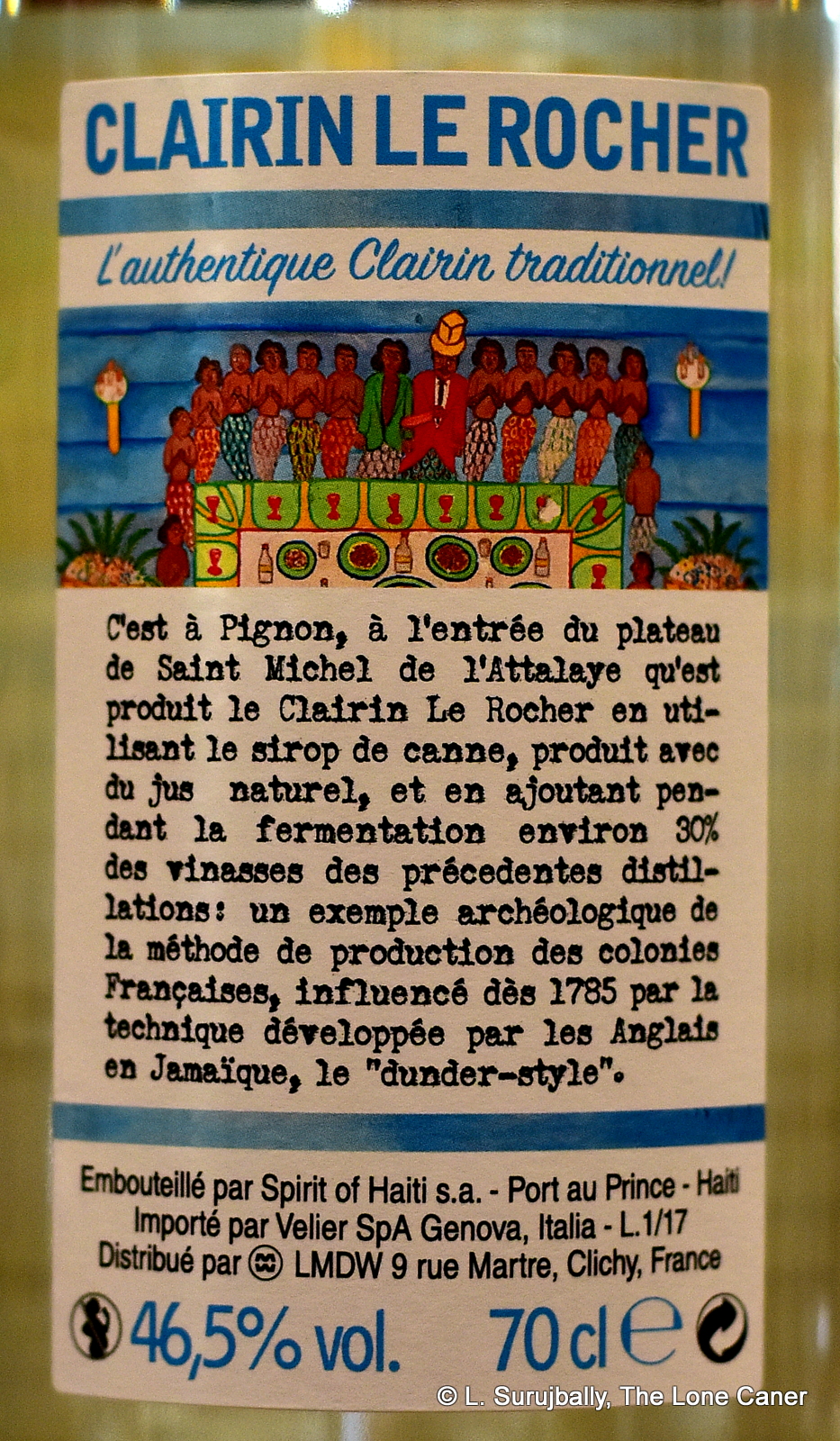

Sometimes a rum gives you a really great snooting experience, and then it falls on its behind when you taste it – the aromas are not translated well to the flavour on the palate. Not here. In the tasting, much of the richness of the nose remains, but is transformed into something just as interesting, perhaps even more complex. It’s warm, not hot or bitchy (46.5% will do that for you), remarkably easy to sip, and yes, the plasticine, glue, salt, olives, mezcal, soup and soya are there. If you wait a while, all this gives way to a lighter, finer, crisper series of flavours – unsweetened chocolate, swank, carrots(!!), pears, white guavas, light florals, and a light touch of herbs (lemon grass, dill, that kind of thing). It starts to falter after being left to stand by itself, the briny portion of the profile disappears and it gets a little bubble-gum sweet, and the finish is a little short – though still extraordinarily rich for that strength – but as it exits you’re getting a summary of all that went before…herbs, sugars, olives, veggies and a vague mineral tang. Overall, it’s quite an experience, truly, and quite tamed – the lower strength works for it, I think.

Sometimes a rum gives you a really great snooting experience, and then it falls on its behind when you taste it – the aromas are not translated well to the flavour on the palate. Not here. In the tasting, much of the richness of the nose remains, but is transformed into something just as interesting, perhaps even more complex. It’s warm, not hot or bitchy (46.5% will do that for you), remarkably easy to sip, and yes, the plasticine, glue, salt, olives, mezcal, soup and soya are there. If you wait a while, all this gives way to a lighter, finer, crisper series of flavours – unsweetened chocolate, swank, carrots(!!), pears, white guavas, light florals, and a light touch of herbs (lemon grass, dill, that kind of thing). It starts to falter after being left to stand by itself, the briny portion of the profile disappears and it gets a little bubble-gum sweet, and the finish is a little short – though still extraordinarily rich for that strength – but as it exits you’re getting a summary of all that went before…herbs, sugars, olives, veggies and a vague mineral tang. Overall, it’s quite an experience, truly, and quite tamed – the lower strength works for it, I think.