Nobody ever accused the Scotch Malt whisky Society of being in a hurry: although they began releasing rums as far back as 2001 (three unnamed releases, from Jamaica, Guyana and Barbados), they seemed none too happy or enthusiastic with the results, for they waited another ten years before issuing another Jamaican (the R1.2 “Rhubarb and Goose-gogs”), then two more in 2012 during Glenmorangie’s tenure at the helm…and then we hung around watching another seven years go by (and new owners take over) before the R1.5 “A Little Extravagant” came out the door in 2019.

As you can imagine, the first issues now command some hefty coin, though thankfully not Velier-esque levels of certifiable insanity (the R1.4 I’m discussing here has been climbing though: £190 in 2016 and £230 two years later on Whisky Auctioneer). This is likely because until Simon Johnson of The Rum Shop Boy blog began reviewing the SMWS rums in his own collection in 2018, most rum people overlooked WhiskyFun’s reviews (or my own 2012 attempts to be funny) few knew anything about the Society’s cane output, or cared much. They were too obscure – the overlap between whisky and rum anoraks had not yet gathered a head of steam – and deemed too expensive.

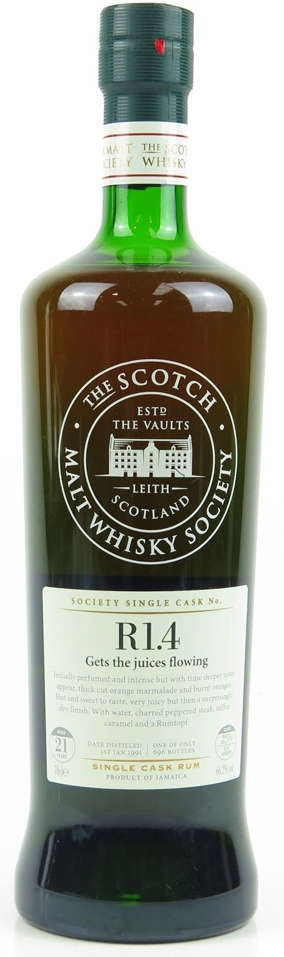

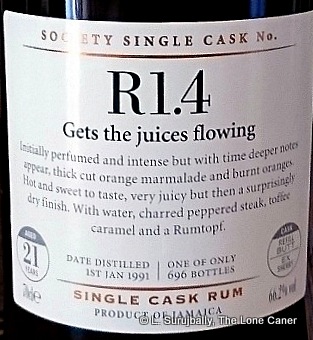

The R1 series (see ‘Other Notes’ below for a quick recap on the numbering schema) of the Society is from Jamaica, Monymusk to be exact and this specific one is from the third issue in 2012, the R1.4, which, in an unconscionable fit of rather reasonable naming, they call “Get the Juices Flowing” … though of course that could describe any Jamaican under the sun. Distilled in 1991, bottled in 2012, the still is unmentioned – however, since Monymusk rum is distilled at Clarendon which has had a columnar still only since 2009, it’s almost certainly a pot still rum. A peculiarity is the outturn: 696 bottles from a “single cask”, which the label helpfully tells us was a sherry butt (likely 500 liters or perhaps more), and as we know from experience, the Society does not muck around with proof but releases it as is from the cask – 66.2% here.

The R1 series (see ‘Other Notes’ below for a quick recap on the numbering schema) of the Society is from Jamaica, Monymusk to be exact and this specific one is from the third issue in 2012, the R1.4, which, in an unconscionable fit of rather reasonable naming, they call “Get the Juices Flowing” … though of course that could describe any Jamaican under the sun. Distilled in 1991, bottled in 2012, the still is unmentioned – however, since Monymusk rum is distilled at Clarendon which has had a columnar still only since 2009, it’s almost certainly a pot still rum. A peculiarity is the outturn: 696 bottles from a “single cask”, which the label helpfully tells us was a sherry butt (likely 500 liters or perhaps more), and as we know from experience, the Society does not muck around with proof but releases it as is from the cask – 66.2% here.

That out of the way, let’s get on to the interesting stuff: a continentally aged rum old enough to vote, from a distillery from which we don’t get such offerings often enough. Nose first: wow, very powerful (66.2%, remember? … that’ll put some hair on the old biscuit-chest). Deep burnt sugar, buttery and caramel notes offset by smoke, almonds, ashes and charred wood (don’t ask) and a cornucopia of fruits: red wine, citrus, green apples, grapes, raisins, dates, prunes, peaches, strawberries….it’s very rich, with hot and spicy fumes and aromas just billowing out of the glass.

The strength manifests itself uncompromisingly and solidly when tasted as well. Trying small sips until one adjusts is probably best here, because then the flavours can be savoured stress free and more easily. And there’s a lot of those, including initial notes, the beginning of tarry smokiness and burning rubber (excuse me? I didn’t think this was a Caroni). There are also light florals, delicate white fleshed fruits, contrasted moments later with more acidic ones – cider, green apples, mangoes, red grapes and the tartness of lemon peel, all twinkling and frisky, plus brine, olives and some salted caramel. The finish is excellent too – long, toasty, cereal-y, crisp herbs, fruit-filled, a lollipop or two, bubble gum, strawberries and that light touch of saline.

While there’s no such notation anywhere on the product page or the bottle itself, clearly someone knew enough to let the esters of the leash here, and balance them carefully with softer tastes to take the edge off. The overall impact is undeniable, and it’s a very impressive dram – very fruity and yet also quite dark and firm in its own way with the caramel, vanilla and brine integrated into the profile very well. There are some weak points here and there, mostly at the inception of smelling and tasting: one’s senses need to become acclimatized to the force blasting out of the glass before true appreciation sets in. But overall, this is as good as any Hampden or Worthy Park rum out there, and it’s only major drawback is that it’s so hard to locate these days.

(#869)(87/100)

Other Notes

- For those new to the Society’s ethos, they don’t name their products, they number them: this stemmed from a practice they had fallen into in the 1980s when whisky distilleries providing single barrels didn’t always want their names associated with this young upstart. Numbers were assigned, one per distillery, plus a second decimal for which release; and funny names — which supposedly were coded references to the taste profile — were added later. With the exception of the first expressions in 2001, rums followed this practice and as of this writing in December 2021, fourteen distilleries in seven countries, all in the Caribbean and Central America are represented. There’s a master list tacked on to the bottom of the Society history which I keep updated as best I can.

- Sincere and grateful hat tip to Simon Johnson, who spotted me this sample when I couldn’t find one. His own review is worth reading.

Opinion

I’ve written and thought about the SMWS more than most indies, because I find their business model very interesting, and most of their rums aren’t bad at all – they just don’t seem to have a firm handle on where they want to go with this aspect of what they do. In terms of their operations, on the surface they are an independent whisky bottler, sourcing barrels from whisky distilleries and releasing them to the market. The main difference is that this market is all subscriber-based and requires membership in the society (at an annual cost, additional to that of the product), and you’ll never see one of their bottles on a shop shelf (unless said shop is a member themselves – and even then, they can only sell to other members).

This creates some interesting commercial dynamics. With thousands of members around the globe and only a few hundred bottles per release (single barrel, remember), it’s inevitable that most people wanting, say, one of the 275 bottles of release 66.177, will be SOL. The society has responded to this inevitable problem by issuing many more expressions in a given period than ever before, from all over the flavour map, and allocating supplies all over the world. They have begun doing blends. Prices are not subject to escalation (except on secondary markets). And of course they have dabbled their toes into other spirits categories as well – gin, bourbon, Armagnac, rum, and so on.

This creates some interesting commercial dynamics. With thousands of members around the globe and only a few hundred bottles per release (single barrel, remember), it’s inevitable that most people wanting, say, one of the 275 bottles of release 66.177, will be SOL. The society has responded to this inevitable problem by issuing many more expressions in a given period than ever before, from all over the flavour map, and allocating supplies all over the world. They have begun doing blends. Prices are not subject to escalation (except on secondary markets). And of course they have dabbled their toes into other spirits categories as well – gin, bourbon, Armagnac, rum, and so on.

One could reasonably argue how this possibly results in an ongoing commercial enterprise: after all, today there are tons of companies selling single cask bottlings and you don’t have to worry about membership dues tacked on to what is already a hefty price (indie bottlings tend to be more expensive than readily available blends or estate bottlings because of their individualistic nature and different cost structures). The SMWS’s success has rested on a number of pillars: first mover advantages – they were among the first to seriously popularize the concept of single barrel unblended whisky sales, at scale (while not inventing it); great barrel selections in their first years; really good marketing; the mystique of exclusivity of a subscriber based society; and the gradual move and expansion into more than just Scottish distilleries’ whiskies – other countries, other spirits and even an ageing programme of their own (they no longer just buy pre-aged casks from distilleries).

Because the Society remains at heart a whisky-based enterprise, rums are unfortunately given short shrift, and even engaging Ian Burrell to be a sort of onboard consultant in 2020 hasn’t helped much – there has been no noticeable improvement or creative explosion on the rum front. The rums that are released are occasionally set at a price difficult to justify, not as varied as they could be (releases remain solely from the Caribbean and Central America in a time of interesting production from around the world) and the lack of real advertising of these products doesn’t engage the broader rum community who could potentially be their greatest cheerleaders. Other better-known and well-regarded indies are running circles around SMWS’s rum portfolio, issuing more, better, more often and with a lot more hooplah, and primary producers are only just getting started themselves. Moreover, the Society’s rums are released with an inconsistency that is problematic by itself: why would anyone fork out an annual subscription fee when one can’t tell whether in a single year this can result in many rums available for purchase, or a few, or one…or none?

So, personally I think that the rum section of the society needs serious work and more attention by someone who can dedicate time and energy to that alone and not dilute their focus with other things. If a 29 year old Guyanese rum or a 23 year old Caroni can cost £275 each and remain on the ”available” list for months, then I think there are underlying issues of price, promotion, awareness and perception of value that must be improved. The Society may be the cat’s meow on the whisky front (though I note that grumbles about availability, price and quality are a constant feature of online discourse), but with respect to rums, they’re nowhere near the front of the pack. And that’s a pity for an aspect of their work that has such potential for growth.

[Note: this opinion is an expansion of observations briefly touched on in the 2020 company profile of the SMWS; also, full disclosure: I am a member of the SMWS myself, focusing solely on their rums].

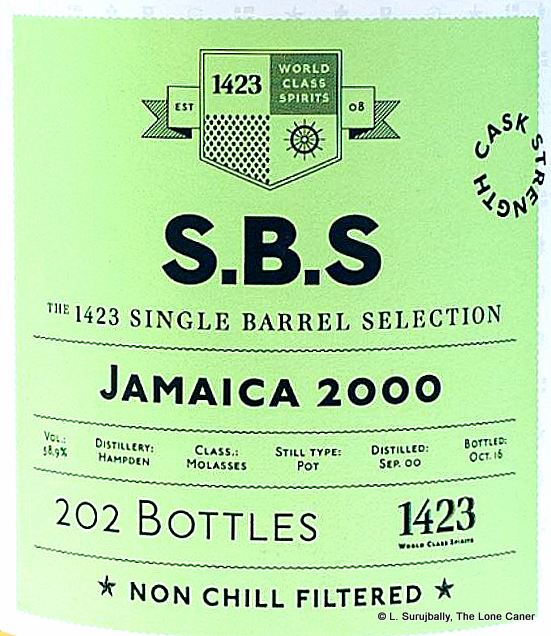

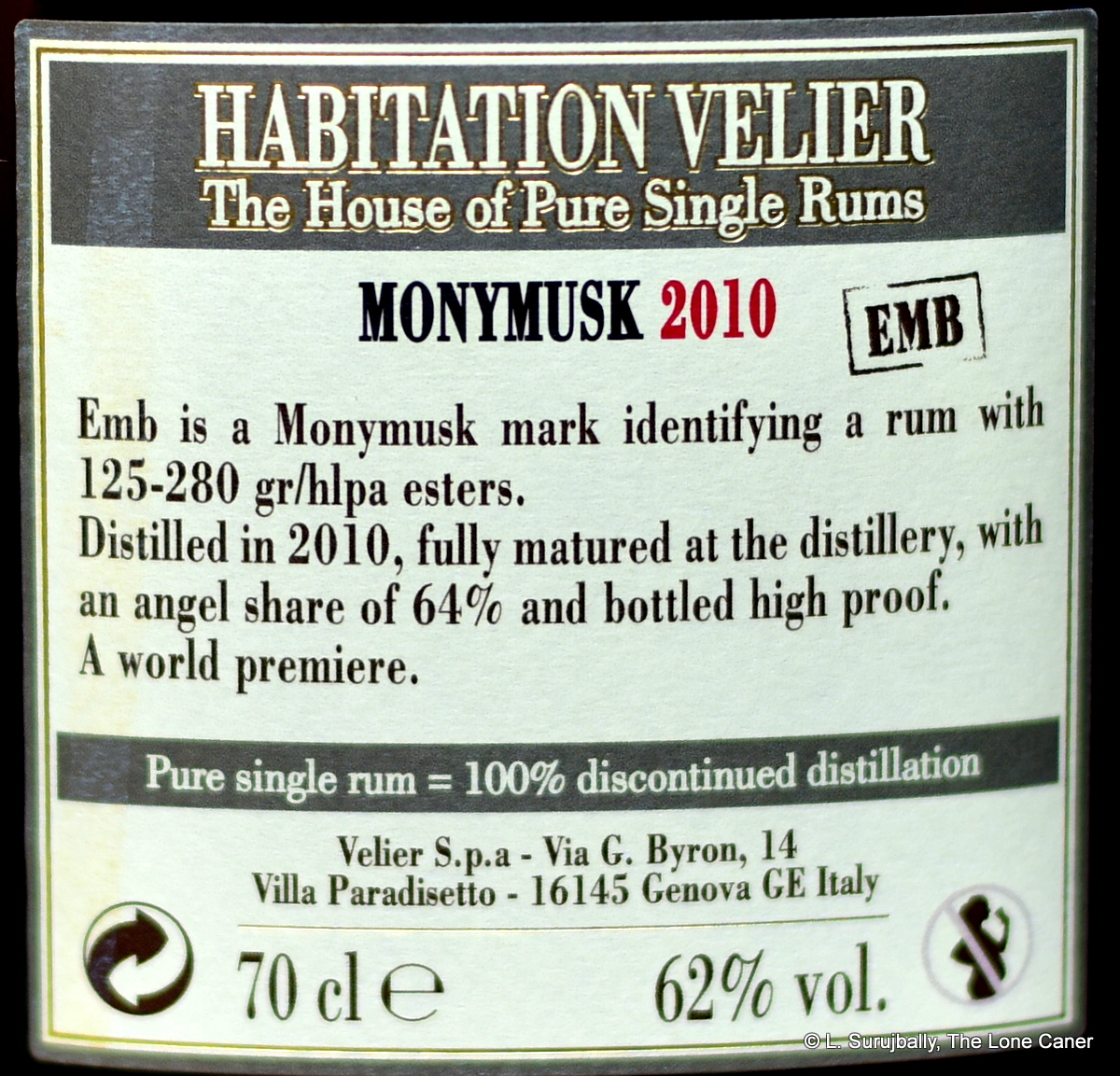

And what a rum it was. I don’t know what ester levels it had, but my first note was “a lot!”. I mean, it was massive. Pencil shavings and glue. Lots of it. Musky, dry, cardboard and damp sawdust. Some rotting fruit (was that dunder they were using?) and also rubber and furniture polish slapped on enough uncured greenheart to rebuild the Parika stelling, twice. The fruitiness – sharp! – of tart apples, green grapes, passion fruit, overripe oranges and freshly peeled tangerines. Florals and crisp light notes, all of it so pungent and bursting that a little breeze through your house and the neighbors would either be calling for a HAZMAT team or the nearest distillery to find out if they had lost their master blender and a still or two.

And what a rum it was. I don’t know what ester levels it had, but my first note was “a lot!”. I mean, it was massive. Pencil shavings and glue. Lots of it. Musky, dry, cardboard and damp sawdust. Some rotting fruit (was that dunder they were using?) and also rubber and furniture polish slapped on enough uncured greenheart to rebuild the Parika stelling, twice. The fruitiness – sharp! – of tart apples, green grapes, passion fruit, overripe oranges and freshly peeled tangerines. Florals and crisp light notes, all of it so pungent and bursting that a little breeze through your house and the neighbors would either be calling for a HAZMAT team or the nearest distillery to find out if they had lost their master blender and a still or two. Rumaniacs Review #123 | #800

Rumaniacs Review #123 | #800

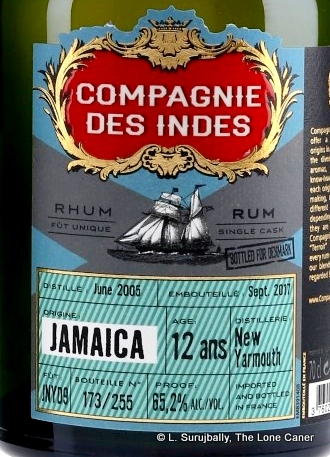

Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with

Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with  The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember

The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember  Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

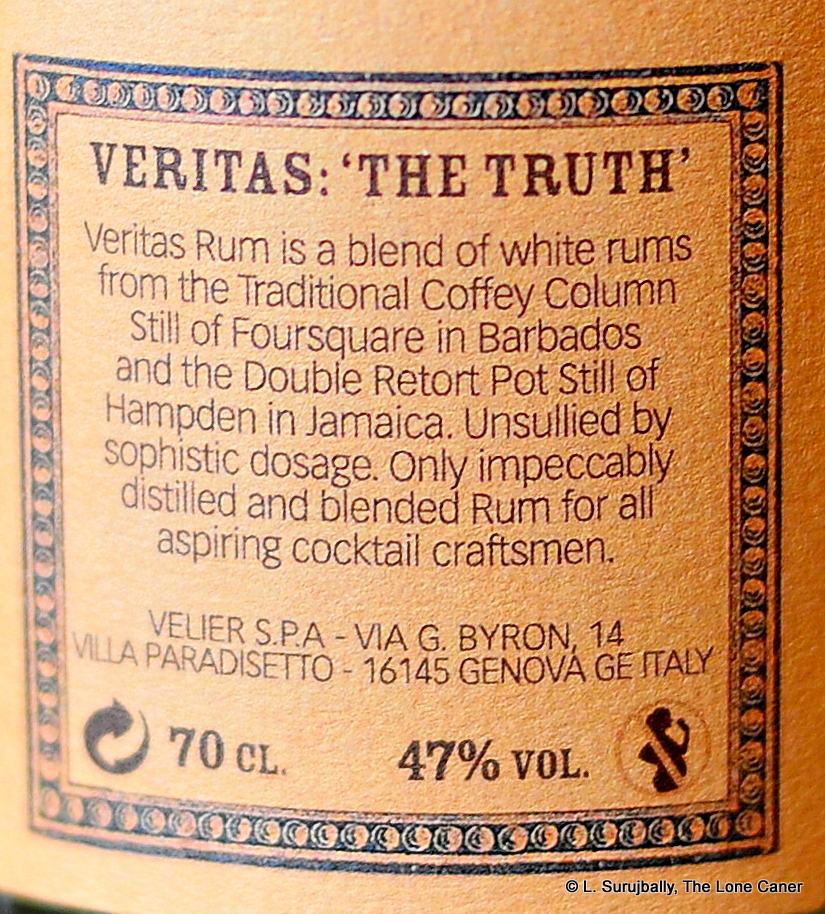

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

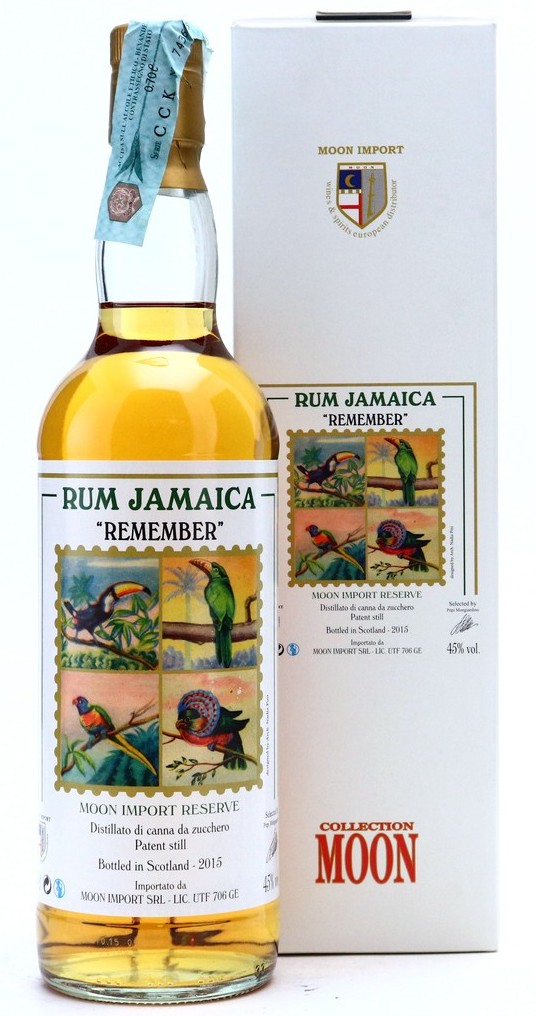

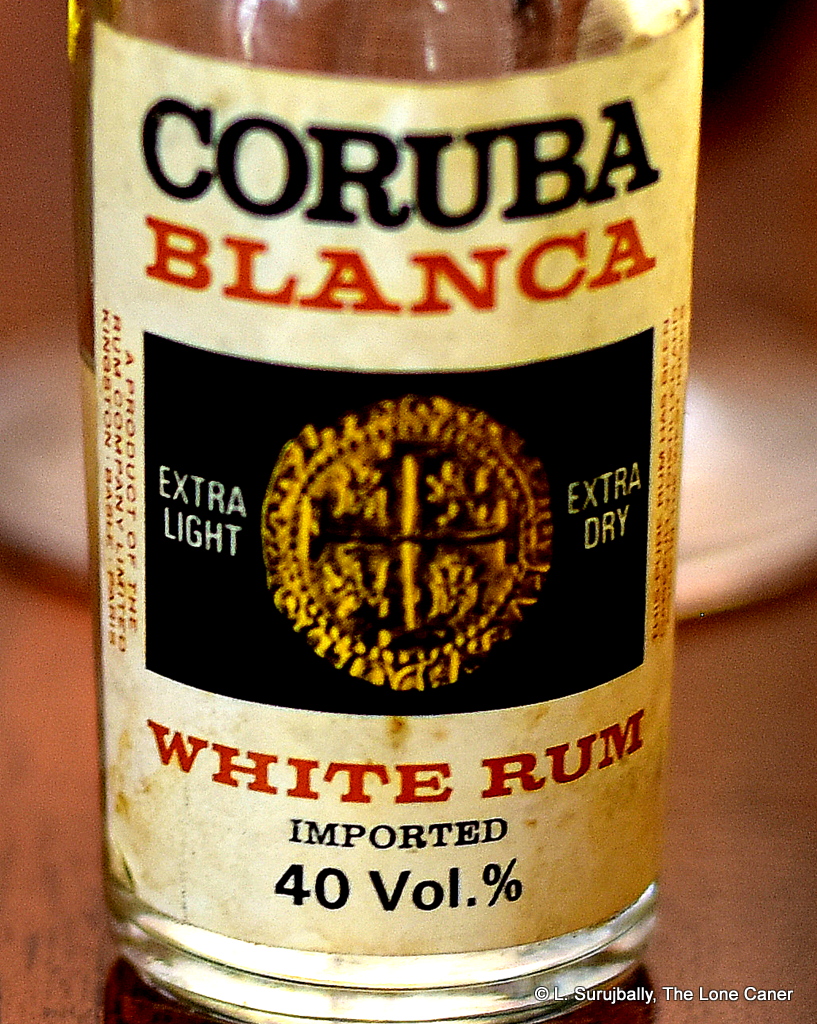

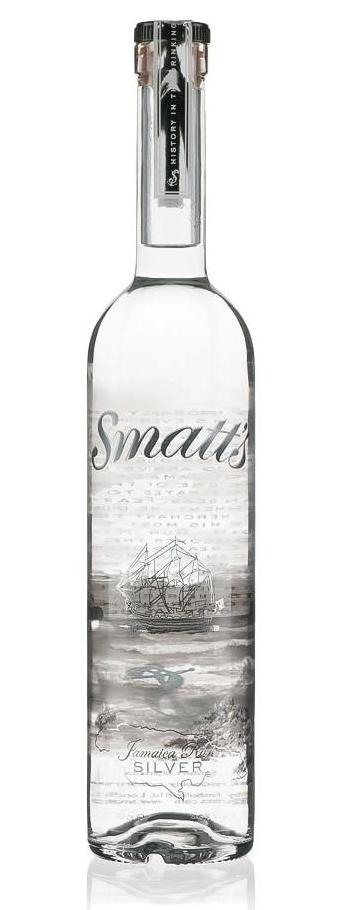

Normally, such a rum wouldn’t interest me much, but with the massive reputations the New Jamaicans have been building for themselves, it made me curious so I grudgingly parted with some coin to get a sample. That was the right decision, because this thing turned out to be less an undiscovered steal than a low-rent Jamaican wannabe for those who don’t care about and can’t tell one Jamaican rum from another, know Appleton and stop there. The rum takes great care not to go beyond such vanilla illusions, since originality is not its forte and it takes inoffensive pleasing-the-sipper as its highest goal.

Normally, such a rum wouldn’t interest me much, but with the massive reputations the New Jamaicans have been building for themselves, it made me curious so I grudgingly parted with some coin to get a sample. That was the right decision, because this thing turned out to be less an undiscovered steal than a low-rent Jamaican wannabe for those who don’t care about and can’t tell one Jamaican rum from another, know Appleton and stop there. The rum takes great care not to go beyond such vanilla illusions, since originality is not its forte and it takes inoffensive pleasing-the-sipper as its highest goal.

As for the finish, well, in rum terms it was longer than the current Guyanese election and seemed to feel that it was required that it run through the entire tasting experience a second time, as well as adding some light touches of acetone and rubber, citrus, brine, plus everything else we had already experienced the palate. I sighed when it was over…and poured myself another shot.

As for the finish, well, in rum terms it was longer than the current Guyanese election and seemed to feel that it was required that it run through the entire tasting experience a second time, as well as adding some light touches of acetone and rubber, citrus, brine, plus everything else we had already experienced the palate. I sighed when it was over…and poured myself another shot.

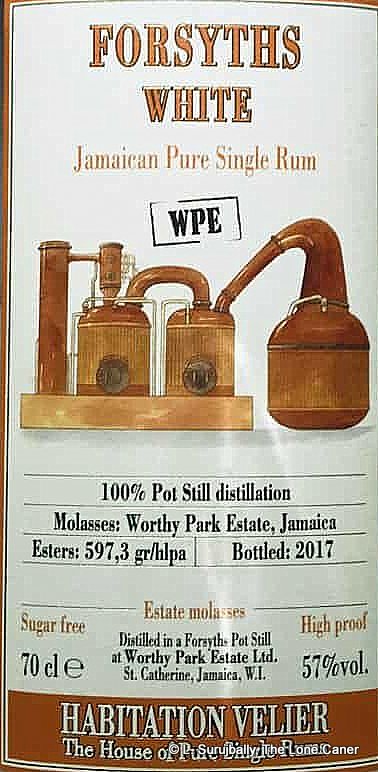

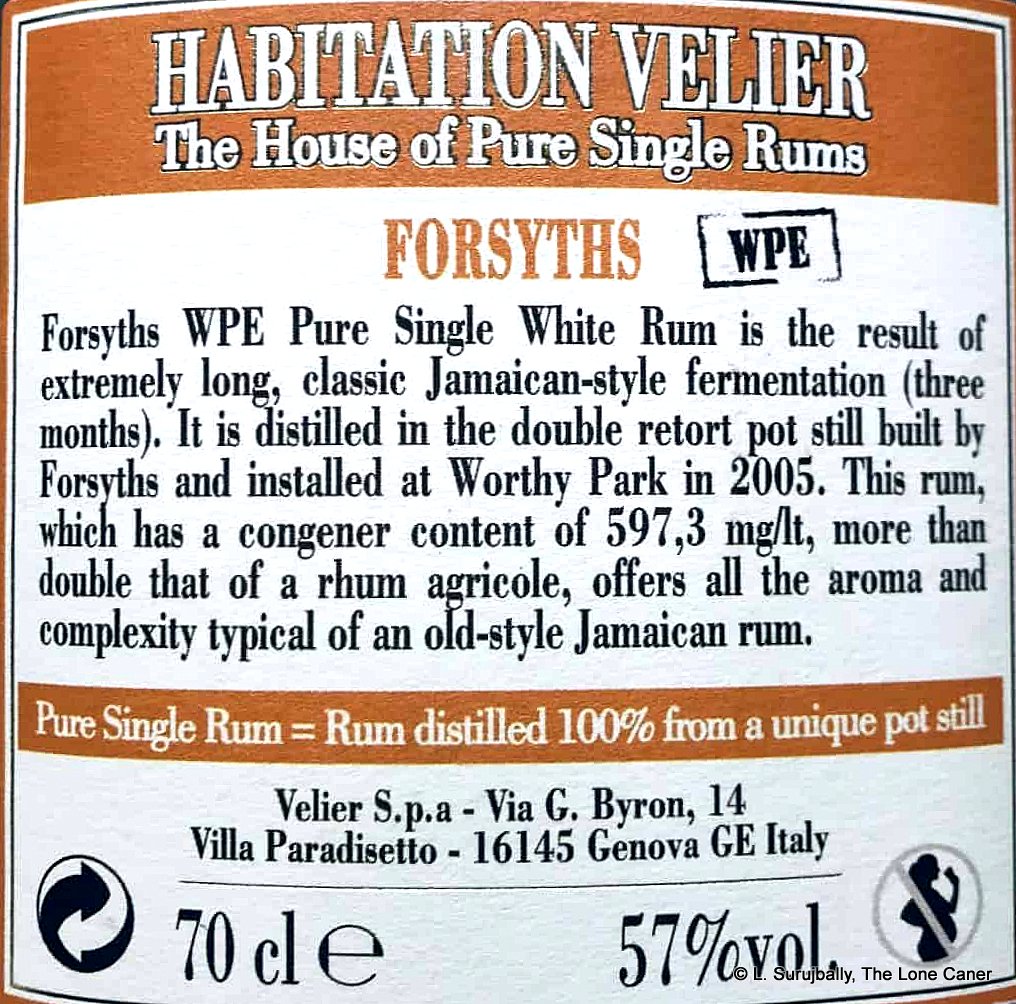

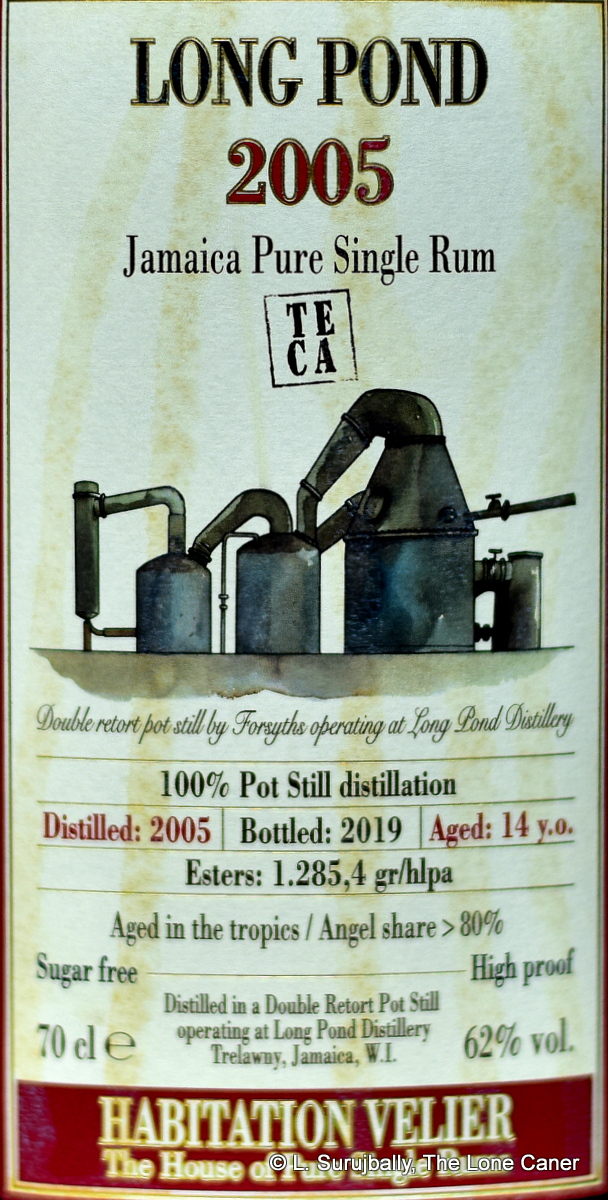

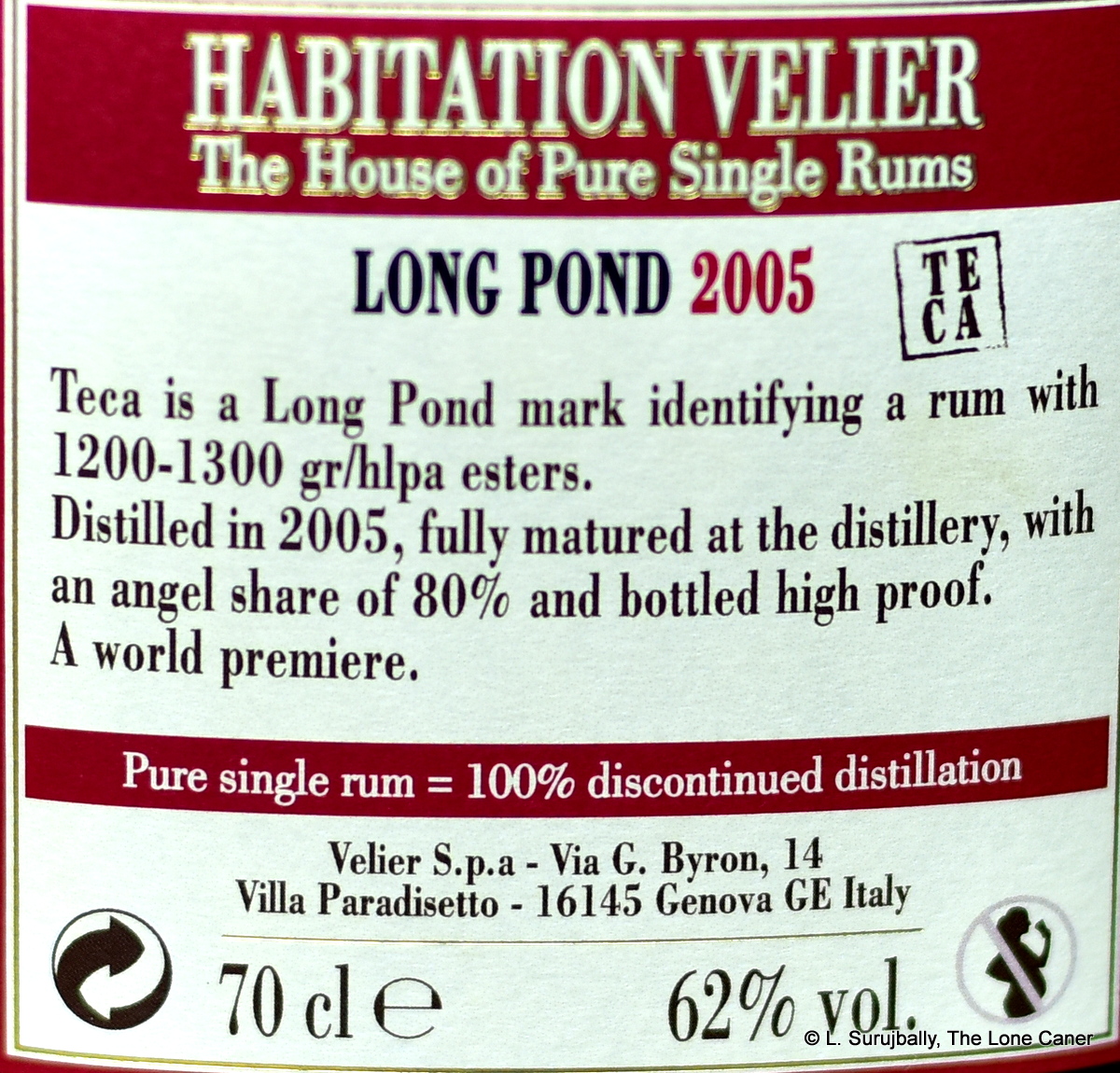

Let’s see if we can’t redress that somewhat. This is a Jamaican rum from Longpond, double pot still made, 62% ABV, 14 years old, and released as one of the pot still rums the Habitation Velier line is there to showcase. I will take it as a given it’s been completely tropically aged. Note of course, the ester figure of 1289.5 gr/hlpa, which is very close to the maximum (1600) allowed by Jamaican law. What we could expect from such a high number, then, is a rum sporting taste-chops of uncommon intensity and flavour, as rounded off by nearly a decade and a half of ageing – now, those statistics made the TECA 2018 detonate in your face and it’s arguable whether that’s a success, but here? … it worked. Swimmingly.

Let’s see if we can’t redress that somewhat. This is a Jamaican rum from Longpond, double pot still made, 62% ABV, 14 years old, and released as one of the pot still rums the Habitation Velier line is there to showcase. I will take it as a given it’s been completely tropically aged. Note of course, the ester figure of 1289.5 gr/hlpa, which is very close to the maximum (1600) allowed by Jamaican law. What we could expect from such a high number, then, is a rum sporting taste-chops of uncommon intensity and flavour, as rounded off by nearly a decade and a half of ageing – now, those statistics made the TECA 2018 detonate in your face and it’s arguable whether that’s a success, but here? … it worked. Swimmingly. So – good or bad? Let’s see if we can sum this up. In short, I believe the 2005 TECA was a furious and outstanding rum on nearly every level. But that comes with caveats. “Fasten your seatbelt” remarked Serge Valentin

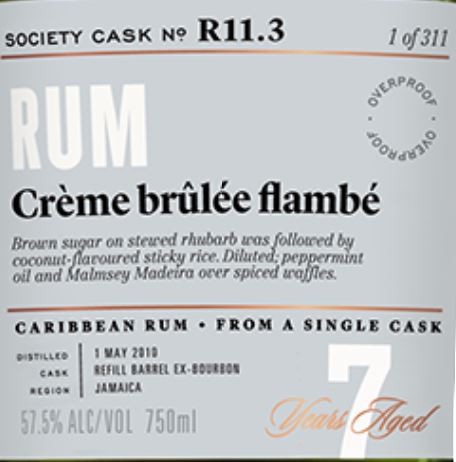

So – good or bad? Let’s see if we can sum this up. In short, I believe the 2005 TECA was a furious and outstanding rum on nearly every level. But that comes with caveats. “Fasten your seatbelt” remarked Serge Valentin  Anyone from my generation who grew up in the West Indies knows of the scalpel-sharp satirical play “Smile Orange,” written by that great Jamaican playwright, Trevor Rhone, and made into an equally funny film of the same name in 1976. It is quite literally one of the most hilarious theatre experiences of my life, though perhaps an islander might take more away from it than an expat. Why do I mention this irrelevancy? Because I was watching the YouTube video of the film that day in Berlin when I was sampling the Worthy Park series R 11.3, and though the film has not aged as well as the play, the conjoined experience brought to mind all the belly-jiggling reasons I so loved it, and Worthy Park’s rums.

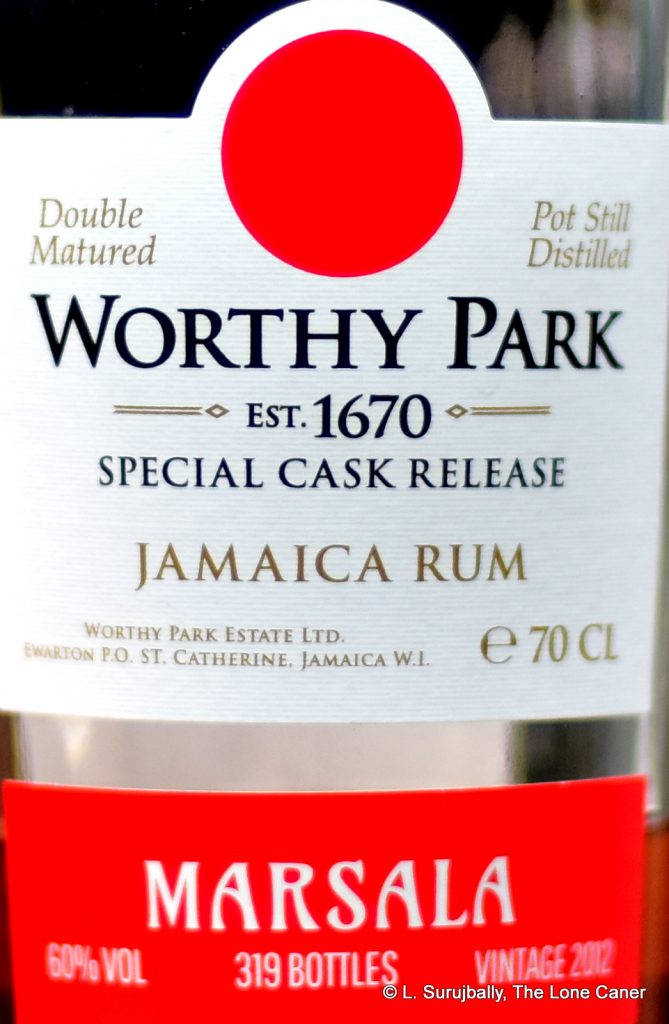

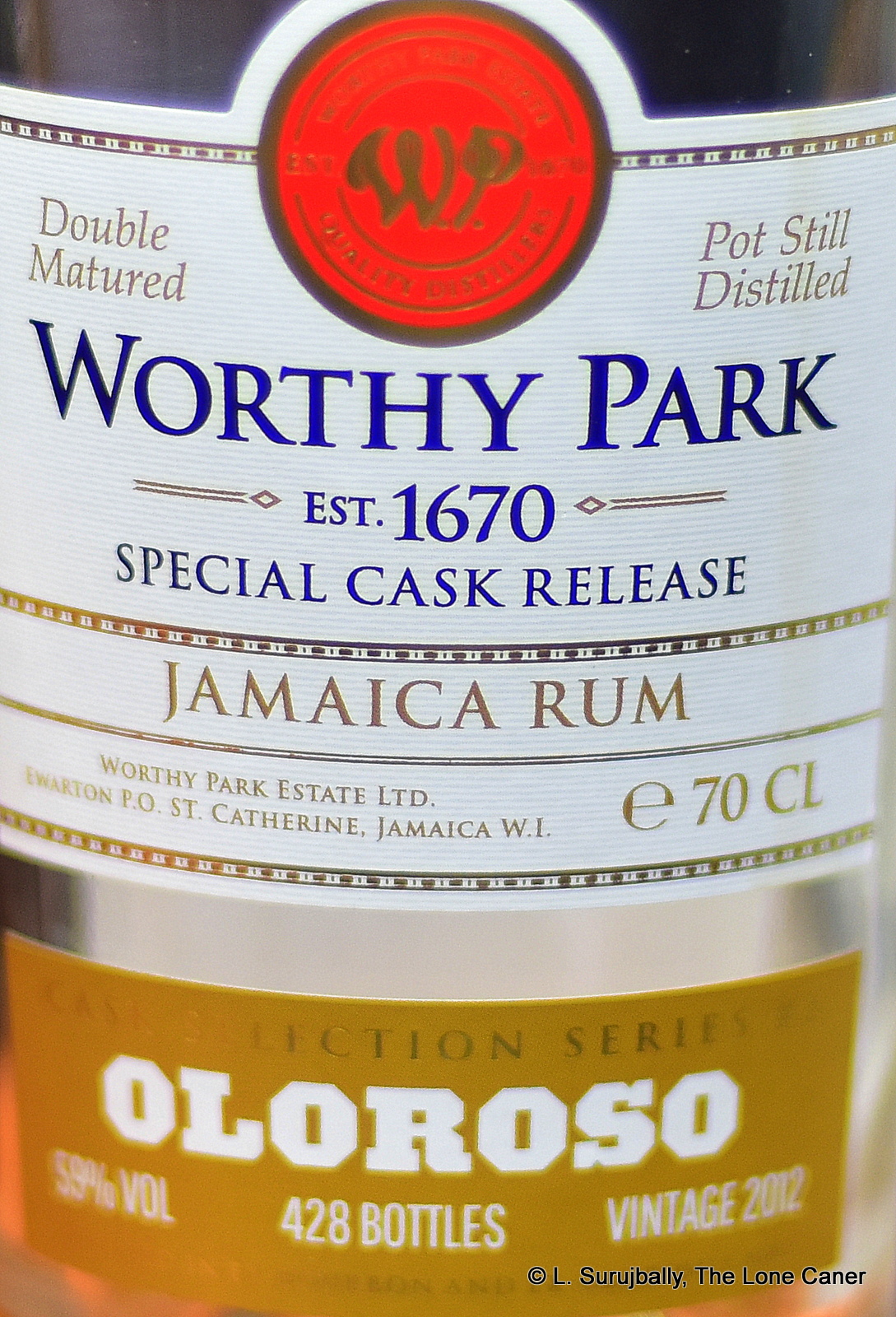

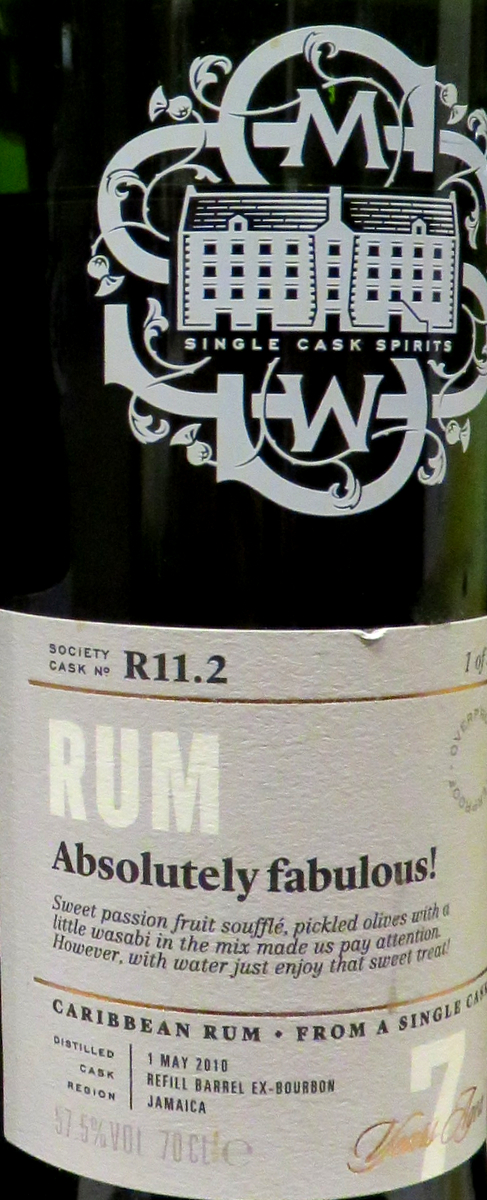

Anyone from my generation who grew up in the West Indies knows of the scalpel-sharp satirical play “Smile Orange,” written by that great Jamaican playwright, Trevor Rhone, and made into an equally funny film of the same name in 1976. It is quite literally one of the most hilarious theatre experiences of my life, though perhaps an islander might take more away from it than an expat. Why do I mention this irrelevancy? Because I was watching the YouTube video of the film that day in Berlin when I was sampling the Worthy Park series R 11.3, and though the film has not aged as well as the play, the conjoined experience brought to mind all the belly-jiggling reasons I so loved it, and Worthy Park’s rums. The distillation run from 2010 must have been a good year for Worthy Park, because the SMWS bought no fewer than seven separate casks from then to flesh out its R11 series of rums (R11.1 through R11.6 were distilled May 1st of that year, with R11.7 in September, and all were released in 2017). After that, I guess the Society felt its job was done for a while and pulled in its horns, releasing nothing in 2018 from WP, and only one more — R11.8 — the following year; they called it “Big and Bountiful” though it’s unclear whether this refers to Jamaican feminine pulchritude or Jamaican rums.

The distillation run from 2010 must have been a good year for Worthy Park, because the SMWS bought no fewer than seven separate casks from then to flesh out its R11 series of rums (R11.1 through R11.6 were distilled May 1st of that year, with R11.7 in September, and all were released in 2017). After that, I guess the Society felt its job was done for a while and pulled in its horns, releasing nothing in 2018 from WP, and only one more — R11.8 — the following year; they called it “Big and Bountiful” though it’s unclear whether this refers to Jamaican feminine pulchritude or Jamaican rums. It sounds strange to say it, but the

It sounds strange to say it, but the