In 2015 an up and coming small rum maker called Plantation wanted to make a bar mixer to go beyond its decently regarded and well-selling Original Dark, which back then was primarily Trinidad distillate. The company had already made a name for itself in the bartending circuit with its blends like the Three Star, and its initial attempts at becoming an indie bottler got some decent reviews (mine among them). People liked them. The secondary maturation abroad and dosage, had not yet become issues. Their rums were deemed pretty good.

In 2015 an up and coming small rum maker called Plantation wanted to make a bar mixer to go beyond its decently regarded and well-selling Original Dark, which back then was primarily Trinidad distillate. The company had already made a name for itself in the bartending circuit with its blends like the Three Star, and its initial attempts at becoming an indie bottler got some decent reviews (mine among them). People liked them. The secondary maturation abroad and dosage, had not yet become issues. Their rums were deemed pretty good.

To the end of filling a gap in the overproof dark rum segment of the mixing market, Alexandre Gabriele the owner, repeated the process he had used to make the Three Star – he consulted with people who were in the industry, and brought together six personages of the rum world whose experiences behind the bar and within the cocktail culture were such that their opinions held real weight: Jeff “Beachbum” Berry from Latitude 29, Martin Cate from Smuggler’s Cove, Paul McFadyen who was then at Trailer Happiness, Paul McGee from Lost Lake, Scotty Schuder from Dirty Dick, and Dave Wondrich, a cocktail historian. Based on lots of samples and lots of tastings (and probably lots of cheerfully inebriated arguments) they set to work to make a mixer that it was hoped would elevate tropical cocktails and Tiki drinks to the next level, take on Lemon Hart and Hamilton’s overproof rums, and carve its own niche in the world.

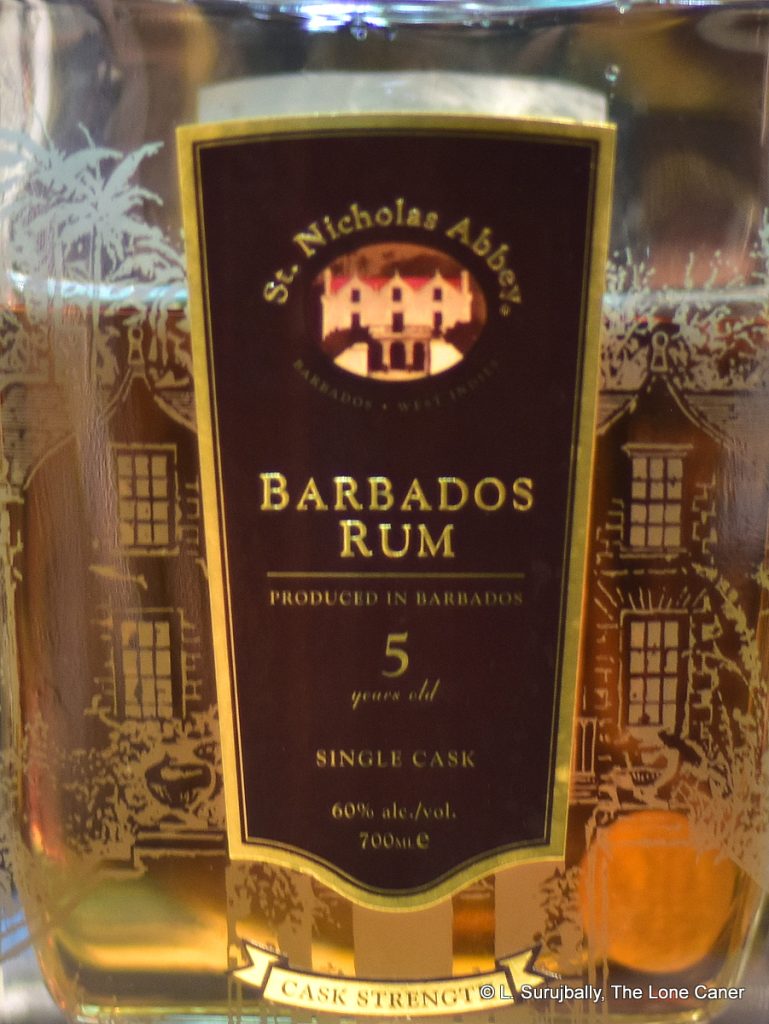

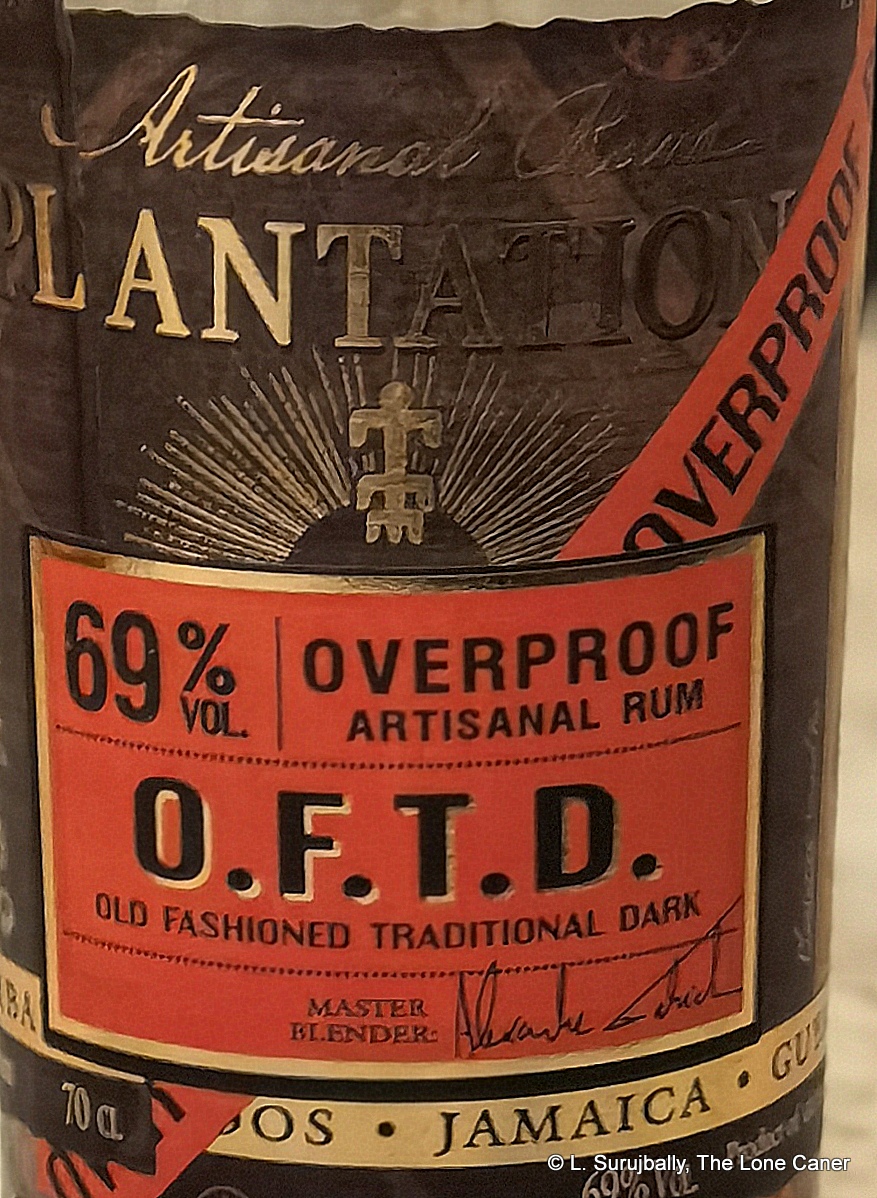

Products designed by committee rarely succeed, but here may be the exception that proves the rule: from that beginning so many years ago, the OFTD, first released in July 2016, has become one of the most popular mixing drinks ever made, perhaps not quite rivalling Bacardi in ubiquity, but so versatile and affordable and let’s face it, even drinkable, that it has become a commercial and private bar staple. Even as the groundswell of dislike for Plantation has grown into ever more poisonous online discourse, the Old Fashioned Traditional Dark, made from rums deriving from Barbados, Guyana, and Jamaica, has flourished. It eclipses every other rum in the company’s “Bar Classic” series of the line (Stiggins’ Fancy and Xaymaca are popular for other reasons); it is a step above and much more interesting than the overly sweet “Signature” blends and surely easier on the wallet than the Single Cask, Extreme or Vintage editions.

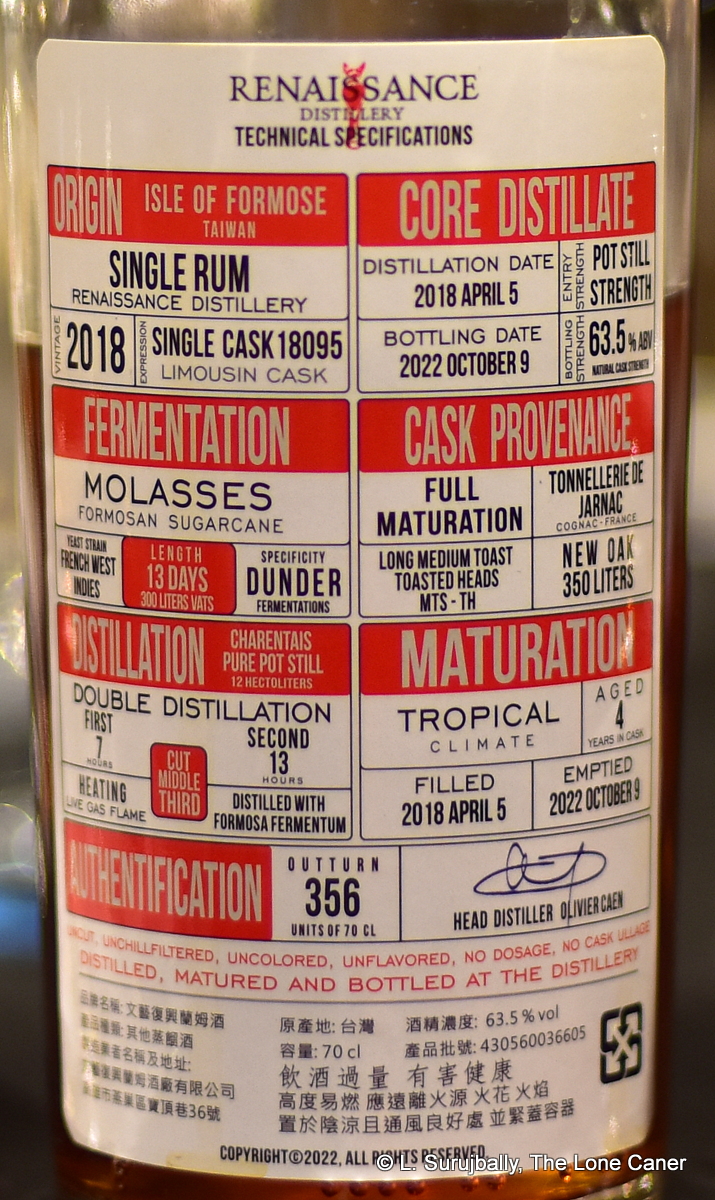

What makes it so popular and so well regarded? To some extent it really is how well the blend works; the strength certainly helps, and for sure so does the lack of any additives – it is one of the few rums Plantation makes which is not dosed. When one looks under the hood, it’s really quite a bit more complex than at first seems to be the case: back in 2018 The ‘Wonk said that the makeup was Guyana (Port Mourant distillate aged 1-2 Years in new and ex-Cognac French oak), Barbados (WIRD distillate, 4 years in new French oak and 2-4 Years in heavy toasted American white oak); and Jamaica (Clarendon MLC 1-2 Years in new French oak, Long Pond TECC 1-2 Years also in new French oak, Long Pond STCE 8½ years in ex-bourbon and ex-Cognac, and lastly some Long Pond TECA 19½ years in ex-bourbon and ex-Cognac). All blended and tied up in a bow at 69% ABV, and while perhaps by 2023 the blend has shifted somewhat, that’s not an inconsiderable amount of taste profiles to be balancing against one other — that anything drinkable comes out at the other end is some kind of minor miracle, because my experience is that blends trying to do so much with so many things, often crash and burn.

Not here, I don’t think. The nose is no slouch and gets going immediately: hot fierce and sharp as befitting the strength, and starting the party off with banana (at one point I got banana bread, at another flambeed), caramel, and brown sugar damp with molasses. Coffee grounds, unsweetened chocolate, anise and allspice are there, leavened with coconut shavings, a touch of anise, brine, and even a mild pinch of citrus. It’s initially quite sharp and alcoholic and it’s recommended to let the glass stand a bit to let that burn off, and once you get there, it’s a nose that sticks around for a long time.

The palate is where one has to make a decision regarding the strength because it is young and it is rough at the inception – many reviews and write ups suggest adding a bit of water to tame it. I don’t think that’s really necessary but then, I have had a lot of rums north of 70% so maybe I’m just used to it. Anyway, the initial palate is all ethanol until it burns off; some rubber and licorice and damp sawdust (that may be the PM talking), molasses and caramel, bitter coffee grounds and chocolate again with traces of ripe mangoes, grapes and even some pineapple (which may be the Jamaican tekkin’ front). There are some vanilla, bon-bons, citrus notes and black pepper here and there, and a finish that oddly reminded me of chocolate oranges mixing it up with salt caramel ice cream topped with a few strawberries…go figure, right?

Evaluating it after trying it maybe four or five times over a period of a year, I get why it’s popular: once you get past the initial burn, you can sip the thing. It is dark, strong, noses nicely and tastes a treat, and such burn and sharp stabs as it displays are, to me, just products of its relative youth (I doubt that there is a whole lot of the aged Longpond elements in there), and in fairness it is designed to be mixed, not sipped. It makes a cool rum and coke of course, and does yeoman’s work in both a daiquiri and a mai tai as well as any other libation a creative bartender can come up with. On top of all that, the damned rum is really affordable: I’ve heard that bars are incentivised with huge cash-back enticements, and that the bulk capacity of WIRD helps keep production costs down, but all that is behind the scenes – this is a rum that subjects itself to the Stewart Affordability Conjecture and takes it seriously.

Evaluating it after trying it maybe four or five times over a period of a year, I get why it’s popular: once you get past the initial burn, you can sip the thing. It is dark, strong, noses nicely and tastes a treat, and such burn and sharp stabs as it displays are, to me, just products of its relative youth (I doubt that there is a whole lot of the aged Longpond elements in there), and in fairness it is designed to be mixed, not sipped. It makes a cool rum and coke of course, and does yeoman’s work in both a daiquiri and a mai tai as well as any other libation a creative bartender can come up with. On top of all that, the damned rum is really affordable: I’ve heard that bars are incentivised with huge cash-back enticements, and that the bulk capacity of WIRD helps keep production costs down, but all that is behind the scenes – this is a rum that subjects itself to the Stewart Affordability Conjecture and takes it seriously.

And if the taste doesn’t sway you, consider the popular statistics. It is a fixture on just about every “with what do I start stocking my home cocktail bar?” recommendation list I’ve ever seen, and the reddit comment sections are filled with people remarking that it’s a rum worth having on any shelf. There is almost no negative review on any subreddit that I’ve looked at, and even those that are less than complimentary usually concede that some aspects of it are fine, or that it has its points here and there and that it’s a moral decision for them not to buy it or stock it. Of the 185 consumer ratings on Distiller from 2016 to 2023, 95% are three-star or higher; on Rum Ratings, nearly 90% out of 257 raters gauged it at 7/10 or better and on Rum-X it has an average of 7.5/10 from 194 people who left a score. These are representative of wide cross sections of the rum drinking public and cannot easily be discounted, whatever one might think of the parent company (and nowadays that is almost all negative). Paul Senft, The Fat Rum Pirate and Rum Shop Boy have all written about it and liked it.

Summing up, the Plantation Old Fashioned Traditional Dark is a deserved yet unusual — perhaps even controversial — entry to the Key Rums series. It is a multi-country blend, not something that showcases a certain country. Yes, it was deliberately created to do only one thing, and therefore its value as an all-round consumer drink is somewhat circumscribed; yes it’s really strong, and sure…in that segment it stays and plays. Yet as I have suggested here, it has qualities over and above all that. It supercedes the modest aims of its creators, to the point where it actually can stand by itself. It remains, nearly a decade after its introduction, one of the most reviewed, commented on and widespread rums around and if its shine is less now than it was when first introduced and now that it has stiffer competition, there is no reason to doubt either its many uses or availability. It remains, for all its parent company’s woes, an incredibly popular and in-use bar staple and drinking adjunct to this day. It demonstrates, if nothing else, how well the Caribbean distillates work with each other in a way that is not often seen. And that’s no mean accomplishment for any rum – especially one made by this outfit – to claim. One can only ask why more of the company’s rums don’t adhere to its philosophy.

(#1038)(84/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other Notes

- In this essay, I have made a deliberate decision to focus on the rum: not to get into the conflict and bad press Plantation gets (or why they get it), not to express my personal opinion on the issues surrounding the company, and to simply mention that such issues exist. There are sufficient resources around — reddit has some good if heated discussions on the matter — for anyone with an interest to find out what the story is.

- I am unsure if any part of the ageing takes place in Europe and was unable to confirm it one way or the other.