The brand of Ron De Mulata is a low end version of Havana Club, established in 1993: it was sold only in Cuba until 2005 when it gradually began to see some export sales, mostly to Europe (UK, Spain and Germany remain major markets). It is a completely Cuban brand, and has expanded its variations up and down the age ladder, from a silver dry rum, aged white, to rons aged 3, 5, 7 and 15 years, plus a Gran Reserva, Palma Superior and even an Elixir de Cuba. It is supposedly one of the most popular rums on the island, commanding, according to some sources, up to 10% of the local market.

Which distilleries make it is a tricky business to ferret out. This one, an aguardiente (see notes on nomenclature, below) is made from juice, and yes, the Cubans did make cane juice rons: it is labelled as coming from Destileria Paraiso (also referred to as Sancti Spiritus, though that’s actually the name of a town nearby), and others of more recent vintage are from Santa Fe, and still others are named. It would appear to be something of a blended cooperative effort by Technoazucar, one of the state-run sugar / rum enterprises (Corporacion Cuba Ron is another).

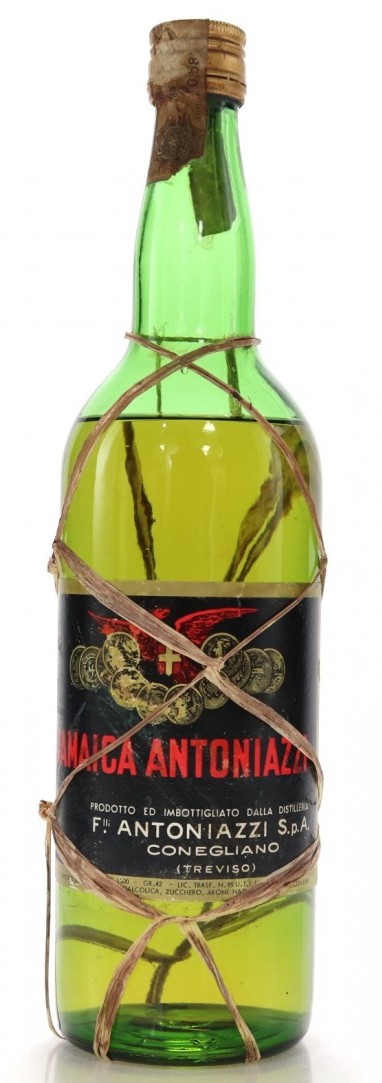

By the time the Mulata rums, including this aguardiente, started seeing foreign sales in 2005, the label had a makeover, because the green-white design on my bottle, with its diagonal separation, has long been discontinued. The lady remains the same (her colour has varied over the decades, and the name of the series makes it clear she is a part-white part black mestizo, or mulata), and the rum is unusual in that it is a cane juice rum to this day. However, since it continues to be made and in the absence of evidence to the contrary, I am making the assumption that for all the updates in bottle and label design, the underlying juice has undergone no significant change and therefore does not qualify for inclusion in the Rumaniacs series. On that basis, it started out, and remains, a white 40% agricole-style rum, hence the title aguardiente.

You would not necessarily believe that when you smell it, though. In fact, it smells decidedly odd on first examination: dusky, briny, with gherkins, olives, some pencil shavings, and lemon peel. This is followed up by herbs like dill and cardamom before doing a ninety degree hard right into laundry detergent, iodine, medicinals, the watery, slightly antiseptic scent of a swimming pool (and yes, I know how that sounds). Fruits are vague at best, and as a purported cane juice rum, this doesn’t much adhere to the profile of such a product.

You would not necessarily believe that when you smell it, though. In fact, it smells decidedly odd on first examination: dusky, briny, with gherkins, olives, some pencil shavings, and lemon peel. This is followed up by herbs like dill and cardamom before doing a ninety degree hard right into laundry detergent, iodine, medicinals, the watery, slightly antiseptic scent of a swimming pool (and yes, I know how that sounds). Fruits are vague at best, and as a purported cane juice rum, this doesn’t much adhere to the profile of such a product.

Upon a hefty shot, it does, however, move closer to what one would expect of such a rum. The shy timidity of the profile is something of a downer, but one can evince notes of iodine (not as bad as it sounds), sugar water, vanilla, grassiness, and watery fruit (pears, white peaches, guavas, unripe pineapples). There’s not much else going on here: the few agricole-like bits and pieces can be sensed, but lack the assertiveness to take them to the next level, and the finish is no help: it’s short, shy, no more than a light breeze across the senses, carrying with it weak hints of green peas, pineapples, and vanilla.

There’s no evidence for this one way or the other, but I think the rum is a filtered white with perhaps a little bit of ageing, and is probably coming off an industrial column still. It lacks the fierce raw pungency of something more down-to-earth made by the peasantry who want to get hammered (so go for greater strength) with no more than a basic ti-punch (so pungent flavours). This rum fails on both counts, and aspires to little more than being a jolt to wake up a hot-weather tropical cocktail. It doesn’t impress.

(#898)(70/100) ⭐⭐

Notes on nomenclature

The use of the word “rum” in this essay is problematic and it has been commented on FB that the product reviewed here cannot be called a rum because (a) it is not made from molasses and (b) it is not aged. I don’t entirely buy into either of those arguments since no regulation in force specifies those two particular aspects as being requirements for naming it either rum (or ron) or aguardiente – though they do prevent it from being called a Cuban rum.

However, there are the traditional rules and modern regulations of the Cuban rum industry which must be taken into account. Under these specifications, an aguardiente is not actually a cane juice rum at all – it is the first distillate coming off the column still, usually at around 75%, retaining much flavour and aroma from the process (this is then blended with the second type of distillate, known as destilado de caña or redistillado which is much higher proofed and has fewer aromas and flavours, being as it is closer to neutral alcohol). By this tradition of naming then, my review subject should not even be called an aguardiente, let alone a rum.

Even the Denominación de Origen Protegida (the DOP, or Protected Designated of Origin) doesn’t specifically reference cane juice, although as per Article 20 rum must come from “raw materials made exclusively from sugar cane”, which doesn’t exclude it. And in Article 21 it mentions that aguardiente – elsewhere and again noted (but not defined or required to be named such) as being the first phase distillate of around 75% ABV – must be aged for about two years and then filtered before going onto be blended. Article 23 lists several different types of añejos but unaged spirits and aguardientes are not mentioned except as before.

This leads us to two possibilities.

- Either what I have reviewed is a bottled first-phase distillate, which means it is aged for two years and a column still distillate deriving from molasses, named as per tradition. This therefore implies that all sources that state it is cane juice origin are wrong.

- This is an unaged cane juice distillate (from a column still), casually named aguardiente because there is no prohibition against using that name, or requirement to use any other term. Given the loose definition of aguardiente across the world, this possibility cannot be discounted.

Neither conjecture eliminates aguardiente as being from some form of sugar cane processing, because it is; and in the absence of a better word, and because it is not forbidden to do so, I am calling it a rum. However, I do accept that it’s a more complex issue than it appears at first sight, and the Cuban regs either don’t cover it adequately (yet), or deliberately ignore the sub-type.