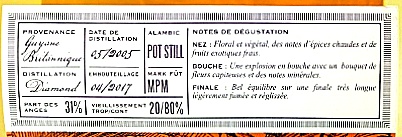

Rumaniacs Review #106 | 0681

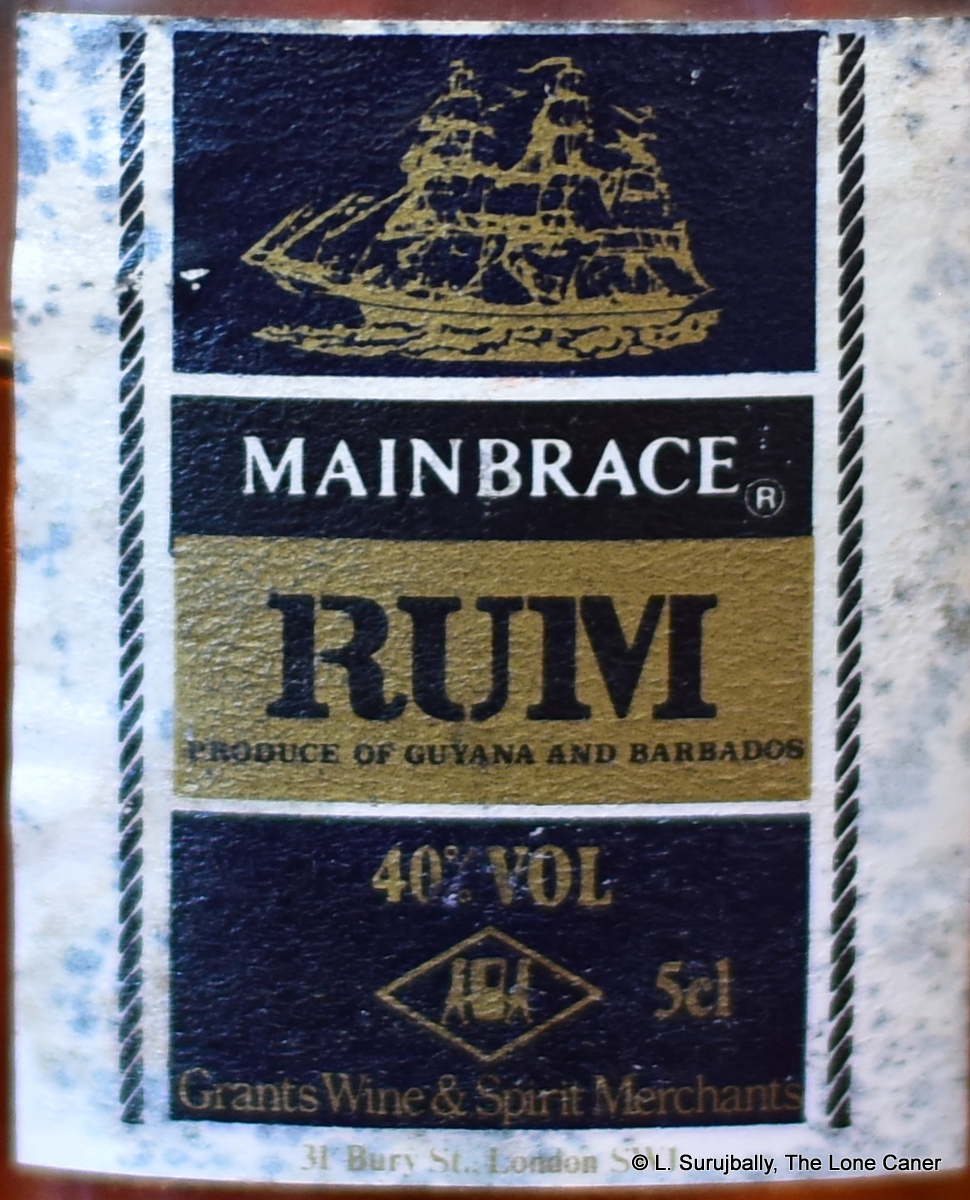

Mainbrace Rum is a Guyanese and Barbados blend released by Grants Wine and Spirits Merchants of London, one of many small emporia whose names are now forgotten, who indulged themselves by selling rums they had imported or bought from brokers, and blended themselves. It is unknown which still’s rums from Guyana were used, or which estate provided the rum from Barbados, though the balance of probability favours WIRR (my opinion). Ageing is completely unknown – either of the rum itself, or its constituents.

The Mainbrace name still exists in 2019, and the concept of joining two rums remains. The fancy new version is unlikely to be associated with Grants however, otherwise the heritage would have been trumpeted front and centre in the slick and one-page website that advertises the Guyana-Martinique blended rum now – in fact, the company that makes it is completely missing from the blurbs.

So what happened to Grants? And how old is the bottle really?

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

Lastly, a new Grants of Saint James was incorporated in 1993 in Bristol, and when I followed that rabbit run, it led me to Matthew Clark plc, a subsidiary of C&C Group since 2018, and there I found that they had acquired Grants around 1990 and at that point it looks like the brand was retired – no references after that date exist. And so I’ll suggest this is a late 1980s rum.

Colour – Dark Amber

Strength – 40% ABV

Nose – Very nice indeed, you can tell there’s a wooden still shedding its sawdust in here someplace. Cedar, sawdust, pencil shavings, plus fleshy fruits, licorice, tinned peaches, brown sugar and molasses. Thick and sweet but not overly so. That Guyanese component is kicking the Bajan portion big time in this profile, because the latter is well nigh unnoticeable…except insofar as it tones down the aggressiveness of the wooden still (whichever one is represented here).

Palate – Dry and sharp. Then it dials itself down and goes simple. Molasses, coca-cola, fruit (raisins, apricots, cashews, prunes). Also the pencil shavings and woody notes remain, perhaps too much so – the promise of the nose is lost, and the disparity between nose and palate is glaring. There is some salt, caramel, brown sugar and anise here, but it’s all quite faint.

Finish – Short, sweet, aromatic, thick, molasses, brown sugar, anise, caramel and vanilla ice cream. Nice, just too short and wispy.

Thoughts – I could smell this thing all day, because that part is outstanding – but the way is tasted and finished, not so much. I would not have pegged it as a blend, because the Guyanese part of it is so dominant. Overall, the 40% really makes the Mainbrace fall down for me – had it been dialled up ten proof points higher, it would have been outright exceptional.

(#681 | R0106)(82/100)

Historical Note

Anyone who’s got even a smattering of nautical lore has heard of the word “mainbrace” – probably from some swearing, toothless, one-legged, one-eyed, parrot-wearing old salt (often a pirate) in some movie somewhere. It is a term from the days of sail, and refers to the rope used to steady – or brace – the (main)mast, stretching from the bow to the top of the mast and back to the deck. Theoretically, then, “splicing the mainbrace” would mean joining two pieces of mainbrace rope – except that it doesn’t. Although originally an order for one of the most difficult emergency repair jobs aboard a sailing ship, it became a euphemism for authorized celebratory drinking afterward, and then developed into the name of an order to grant the crew an extra ration of rum or grog.

Other

Hydrometer rates it 36.24% ABV, which works out to about 15 g/L additives of some kind.

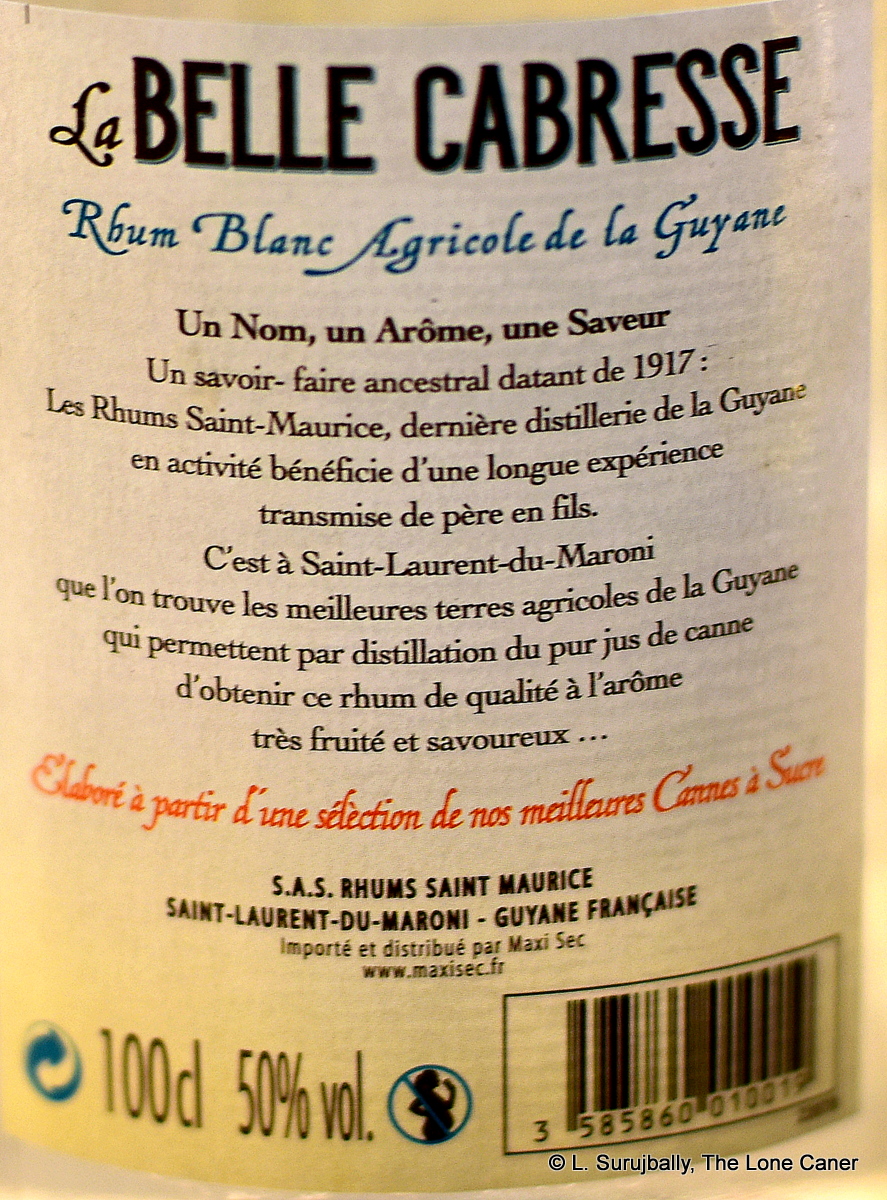

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

This is a rum that has become a grail for many: it just does not seem to be easily available, the price keeps going up (it’s listed around €300 in some online shops and I’ve seen it auctioned for twice that amount), and of course (drum roll, please) it’s released by Richard Seale. Put this all together and you can see why it is pursued with such slack-jawed drooling relentlessness by all those who worship at the shrine of Foursquare and know all the releases by their date of birth and first names.

This is a rum that has become a grail for many: it just does not seem to be easily available, the price keeps going up (it’s listed around €300 in some online shops and I’ve seen it auctioned for twice that amount), and of course (drum roll, please) it’s released by Richard Seale. Put this all together and you can see why it is pursued with such slack-jawed drooling relentlessness by all those who worship at the shrine of Foursquare and know all the releases by their date of birth and first names.

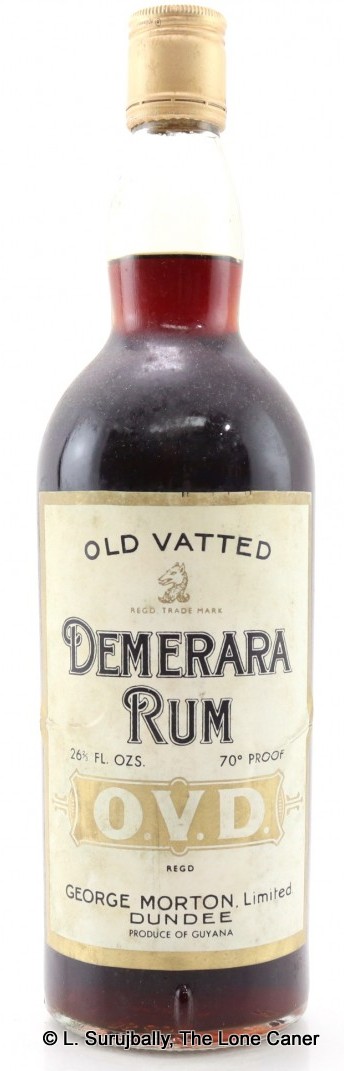

This bottle notes George Morton, founded in 1838, as being located in Dundee which the OVD history page confirms as being the original offices. But a 1970s-dated Aussie listing for a 40% ABV OVD rum already shows them as being located in Glasgow, and a newer bottle label shows Talgarth Rd in London, so my Dundee edition has to be earlier. Lastly, an auction site lists a similar bottle from the 1970s with a label also showing Dundee, and a spelling of “Guyana”, so since the country became independent in 1966, I’m going to suggest the early 1970s is about right

This bottle notes George Morton, founded in 1838, as being located in Dundee which the OVD history page confirms as being the original offices. But a 1970s-dated Aussie listing for a 40% ABV OVD rum already shows them as being located in Glasgow, and a newer bottle label shows Talgarth Rd in London, so my Dundee edition has to be earlier. Lastly, an auction site lists a similar bottle from the 1970s with a label also showing Dundee, and a spelling of “Guyana”, so since the country became independent in 1966, I’m going to suggest the early 1970s is about right

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the  With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

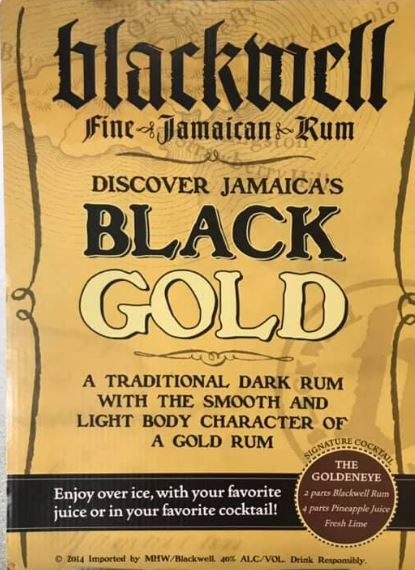

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in  With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

Consider first the nose of this

Consider first the nose of this

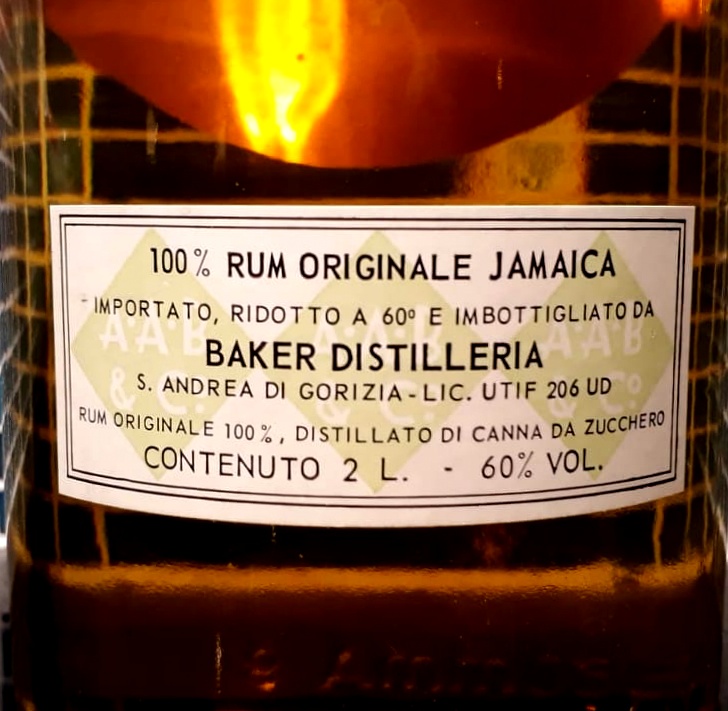

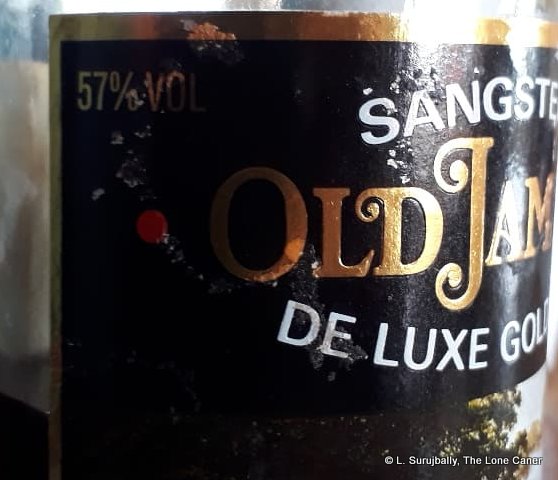

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued.

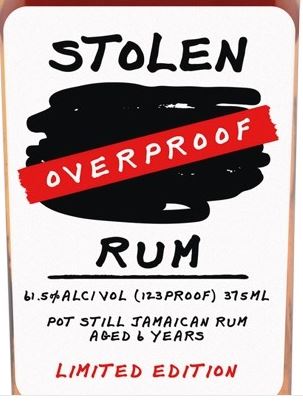

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued. Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.

Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.  Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones.

Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones. Rumaniacs Review # 096 | 0617

Rumaniacs Review # 096 | 0617