Renegade is – or was, in its previous incarnation – the inheritor of the rum work done by Murray McDavid, a bottler of scotch whisky established in 1996, and which acquired Bruichladdich in 2000 (Bruichladdich was itself formed in 1881, changed ownership many times until its acquisition by MM). Renegade was formed as a separate company under this umbrella in 2006 (with a single one-pound share) and their first edition of four vintages was released the following year, with a further six in 2008 and more thereafter. Only three years of releases formed the backbone of the company’s rums (if one discounts the single bottling issued in 2012) and then the operation just wrapped up the whole show.

The story I heard was that the success and positive word of mouth of the Murray McDavid limited edition rums – one of their rums was rated as among the world’s top 50 spirits in 2006 by the Malt Enthusiast – suggested that it might be possible to not only move up the ladder into stronger proofed drinks (46%, when the standard was 40%), but into higher price brackets altogether. Too, they spotted a niche in the rum market that would leverage their distribution systems and existing customer base into a new area (high end limited editions) while perhaps even giving whisky lovers a chance to move into another spirit that was quite similar. This tactic presaged much of what has gone on to become canon in the next decade, and while I would not say it was particularly original – Velier and Rum Nation were already on the scene, if only with minimal exposure, and the other whisky makers like A.D Rattray and Gordon & MacPhail also had such rum bottlings from time to time – such things as finishings were new at the time, and overall it certainly upped the game considerably.

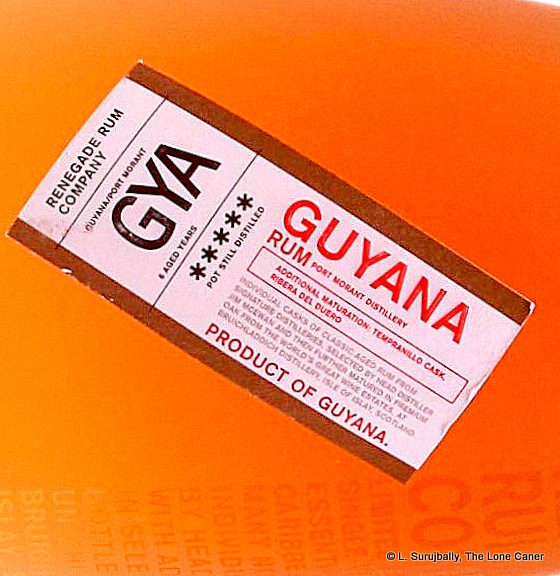

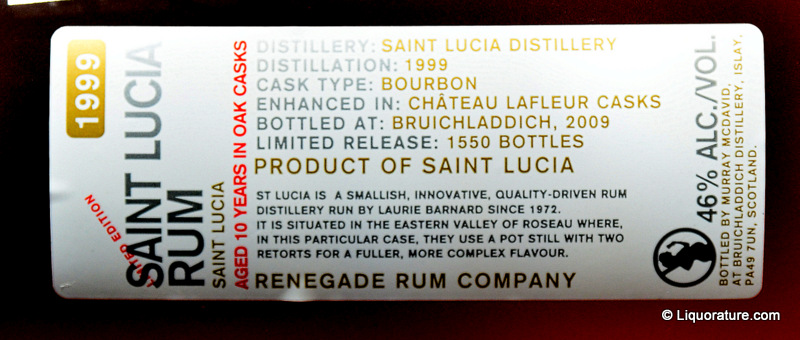

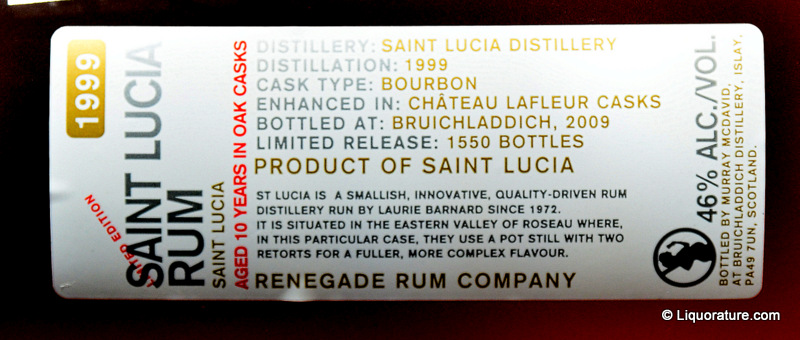

So, Renegade as a brand was a departure from the MM label – they aimed upscale with beautifully etched frosted-glass bottles that were instantly recognizable, and for each of their rums there was a fancy wine finish. Also – and again, somewhat ahead of the modern ethos, though perhaps they were simply channelling Velier (who at the time was a virtual unknown outside of Italy) their labels were masterpieces of concise information – dates of distillation and bottling, the wine casks used to finish them, the estate or plantation or company of origin of the distillate, and a note regarding its unfiltered, unadded-to status, which also was just beginning to get some attention in those years.

The man most closely identified with the rise of Renegade was Mark Reynier, one of the original founders of Murray McDavid back in 1996, who was also instrumental in acquiring Bruichladdich in 2000, by which time that distillery had been dormant for six years. After rebuilding the distillery he turned back to his ideas regarding rums, which had crystallized in the years since Murray McDavid had done their releases (also under his aegis). “We started the company as an independent bottler extension of Murray McDavid,” he wrote to me. “At the time it was relatively easy to get mature and interesting single estate rums, many from obsolete distilleries. It was an extension of our Scotch whisky ethos, providing more interesting bottling from casks married together to create more balance and harmony than the somewhat simplistic single cask bottling fad that did not, we felt, recognise the characteristics of individual barrels where every barrel was bottled regardless of its quality. For this reason we rarely bottled single casks…as we found few that truly, from a professional tasters’ perspective, merited being on their own.”

What this meant was that right from the inception, the release of a few hundred bottles from a single cask was not on the agenda, and Renegade preferred to marry several casks at once, much as Rum Nation does. This gave the double benefit (to them) of being able to create the precise flavour profile they were after without the batch variation of single barrels coming into play – weaknesses in one cask evened out by the mixing with others – as well as having a larger outturn, sometimes around 1500-2000 bottles, but occasionally as much as 4000 (or more). Note that as far as I was able to establish, the barrels were bought from the source distilleries and shipped to Bruichladdich’s premises for maturation, so none of these rums were tropically aged, which became its own trend in the age we’re currently living through.

What this meant was that right from the inception, the release of a few hundred bottles from a single cask was not on the agenda, and Renegade preferred to marry several casks at once, much as Rum Nation does. This gave the double benefit (to them) of being able to create the precise flavour profile they were after without the batch variation of single barrels coming into play – weaknesses in one cask evened out by the mixing with others – as well as having a larger outturn, sometimes around 1500-2000 bottles, but occasionally as much as 4000 (or more). Note that as far as I was able to establish, the barrels were bought from the source distilleries and shipped to Bruichladdich’s premises for maturation, so none of these rums were tropically aged, which became its own trend in the age we’re currently living through.

Reception of the Renegade rum line was positive if not spectacular, which was why in 2009 the outturn increased to ten separate bottlings from nine different islands/countries. However there were already clouds on the horizon dating back to Murray McDavid days. According to Mr. Reynier, as existing stocks were utilized, the quality of casks available for purchase became somewhat repetitive – more of the same, so to speak – and this was one reason why the finishing took on such a central role in the Renegade line (as it was not the under MM). They called it Additional Cask Evolution and sought, very much as Foursquare is doing right now, to enhance the work of the barrel by using other, non-bourbon casks. “We started … Additional Cask Evolution in different, more interesting [casks], to try and bring some much needed vibrancy to the spirit. Poor wood policy is as much a function of the industry’s attitude to economic efficiency…or lack of resources to buy good, fresh wood — and therefore [such rum and whisky companies] excessively re-used old, tired wood.”

Finally, even after such a short period of time, obtaining interesting and good quality barrels which adhered to Renegade’s exacting philosophy became a problem, and the extra remedial work became too onerous (similar issues afflicted MM – in short, “the hassle outweighed the benefits,” as Mr. Reynier opined), and this led to no releases at all for 2010 and 2011, with a single bottling being issued in 2012 – though by this time the writing was already on the wall and it was clear that Renegade was not going to continue along this path, whether for poor sales returns, too much money tied up in warehousing, or the imminent disposition of the company. In early 2013, Bruichladdich, Renegade and Murray McDavid were acquired by Rémy Cointreau, with MM subsequently resold to UK based company Aceo Limited. Mr. Reynier did not continue with any of these companies (see below), although he did retain the Renegade brand name.

Stripped of all the verbiage, this is a remarkably short history for any rum company, and twenty-one releases over seven years is hardly a spectacular outturn. But I believe – with no disrespect to or lack of love for, the other names in the indie rum industry that have survived and thrived to this day – that Renegade was, in its own way, something of a pioneer, and demonstrated the way forward for the independent bottlers. Even though Samaroli, Veronelli, Fassbind, Moon Imports, Silver Seal, Velier and Rum Nation (among others) were already on the scene, and had been for many years, they stayed within a narrow geographical confine (mostly Italy) and issued single cask bottlings that attracted little attention outside the rabid cognoscenti. Renegade was among the first of the Scottish whisky makers to throw the weight of their whisky operations and associated brand awareness behind what was seen then as a niche market — and a small one at that. They were not the first to issue a series of rums at once, of course, but they sure elevated the profile, and certainly they were among the most consistent users of the finishing idea across the entire lineup. Plus – and how could you deny this? – those bottles, man…they were so damned cool, y’now? “Rum Unplugged”, Mark Reynier remarked once, referring to the brand. He sure wasn’t kidding about that.

Stripped of all the verbiage, this is a remarkably short history for any rum company, and twenty-one releases over seven years is hardly a spectacular outturn. But I believe – with no disrespect to or lack of love for, the other names in the indie rum industry that have survived and thrived to this day – that Renegade was, in its own way, something of a pioneer, and demonstrated the way forward for the independent bottlers. Even though Samaroli, Veronelli, Fassbind, Moon Imports, Silver Seal, Velier and Rum Nation (among others) were already on the scene, and had been for many years, they stayed within a narrow geographical confine (mostly Italy) and issued single cask bottlings that attracted little attention outside the rabid cognoscenti. Renegade was among the first of the Scottish whisky makers to throw the weight of their whisky operations and associated brand awareness behind what was seen then as a niche market — and a small one at that. They were not the first to issue a series of rums at once, of course, but they sure elevated the profile, and certainly they were among the most consistent users of the finishing idea across the entire lineup. Plus – and how could you deny this? – those bottles, man…they were so damned cool, y’now? “Rum Unplugged”, Mark Reynier remarked once, referring to the brand. He sure wasn’t kidding about that.

So, I cannot make the case for any kind of incredible reputation or groundbreaking rum philosophy which the company garnered for itself. They exited the business, and many of their bottles rested unsold in Alberta shops for many years, unknown and unappreciated – I picked up several just by driving around, and I’m sure that they can still be picked up to this day by the enterprising rumhound. And yet, and yet….the rums they made remain curiously alive in the memories of those who tried them (I’m one of those weird beings), and may even, I can hope, grow in reputation in the future…if they can still be found. They were larger than usual outturns of a now almost forgotten, largely unreviewed independent bottlers’ philosophy, and deserve a look – whatever one’s final opinion might be – for perhaps that reason alone.

Postscript:

Mr. Reynier’s conclusion in the nineties when he was working with Murray McDavid, was that for full control of the quality of distillation and wood meant one had to have a distillery — he was referring to whisky, and has since extended his thinking on the subject, to encompass rums. He thought about the matter ever since, searching for a suitable rum distillery project or functioning distillery to buy, but never finding the proper one, and concluded he would have to start from scratch. That project came to fruition in Grenada, where for the last two years he has been involved in propagating seven different varieties of cane on Grenada, with a new, modern distillery on the cards, which is expected to go operational by 2019 – in July 2018 ground was broken, foundations are expected to be completed by October, steel frames by December and machinery installed by the first quarter of 2019. By July of that year, distillation operations are expected to commence, and then this post will have to be updated again, though what with laying down stocks to age, the earliest we can expect a rum from Renegade is perhaps 2021.

The new operation will be called the New Renegade Rum Distillery, and so (if you’ll forgive my little bon mot), the brand which was thought to have bought the farm has in fact been resurrected and established another one. The plan is, with Graham Williams of Westerhall, to release an interesting new range of independently bottled rums from this Grenadian base, under a revitalised Westerhall label.

Other notes

My source for much of this essay is Mr. Reynier and online web pages. But perhaps I should take the time to tip my hat – twice – to all those employees of the company who were involved in making this brand but who are so rarely acknowledged.

Compliments to Marco Freyr , whose MM/Renegade biography and bottle list was my first stop. Just as Serge Valentin is the gold standard for tasting notes, Marco is the man for historical detail.

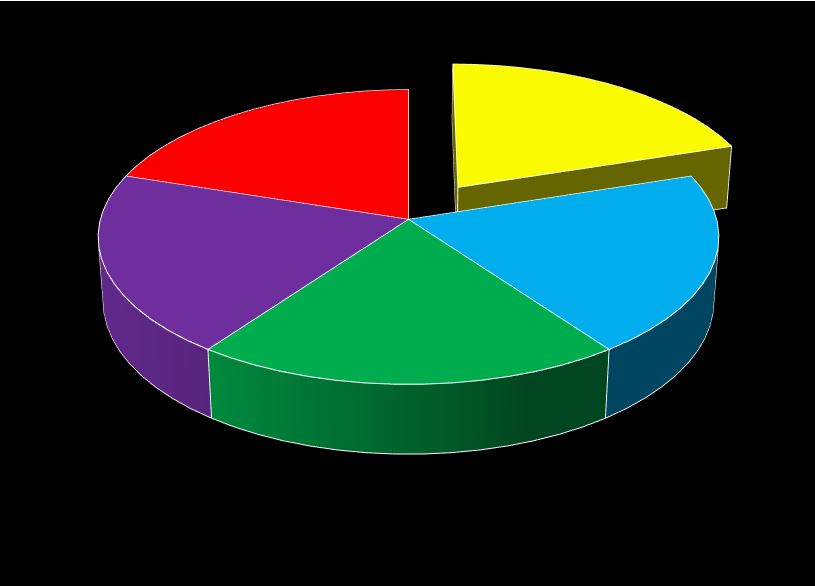

Bottlings

2007

- Guyana, Enmore Distillery, 16 YO (1990-2007), Madeira Finish (1180 bottles)

- Guyana, Uitvlugt Distillery, 12 YO (1995-2007), Chateau d’Yquem Finish (1300 bottles)

- Jamaica, Hampden Distillery, 15 YO (1992-2007), Chateau Latour Finish (1060 bottles)

- Panama, Don Jose Distillery, 10 YO (1997-2007), Port Finish (1380 bottles)

2008

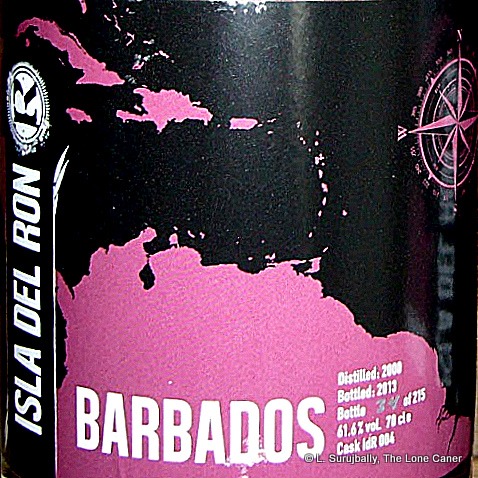

- Barbados, Blackrock Distillery, 8 YO (2000-2008), Port Finish (1590 bottles)

- Grenada, Westerhall Distillery, 11 YO (1996-2008), Chateau Haut Brion Finish (1260 bottles)

- Guyana, Enmore Distillery, 19 YO (1988-2008), Chateau Latour Finish (1020 bottles)

- Jamaica, Hampden Distillery, 8 YO (2000 2008), Chateau Climens Finish (1500 bottles)

- Panama, Don Jose Distillery, 13 YO (1995-2008), Chateau Margaux Finish (1080 bottles)

- Trinidad, Angostura Distillery, 16 YO (1991-2008), Chateau Lafite Finish (1200 bottles)

2009

- Barbados, Blackrock Distillery, 9 YO (2000-2009), Chateau Petrus Finish (1250 bottles)

- Barbados, Foursquare Distillery, 6th YO (2003 – 2009), Banyuls Finish (3870 bottles) VIDEO

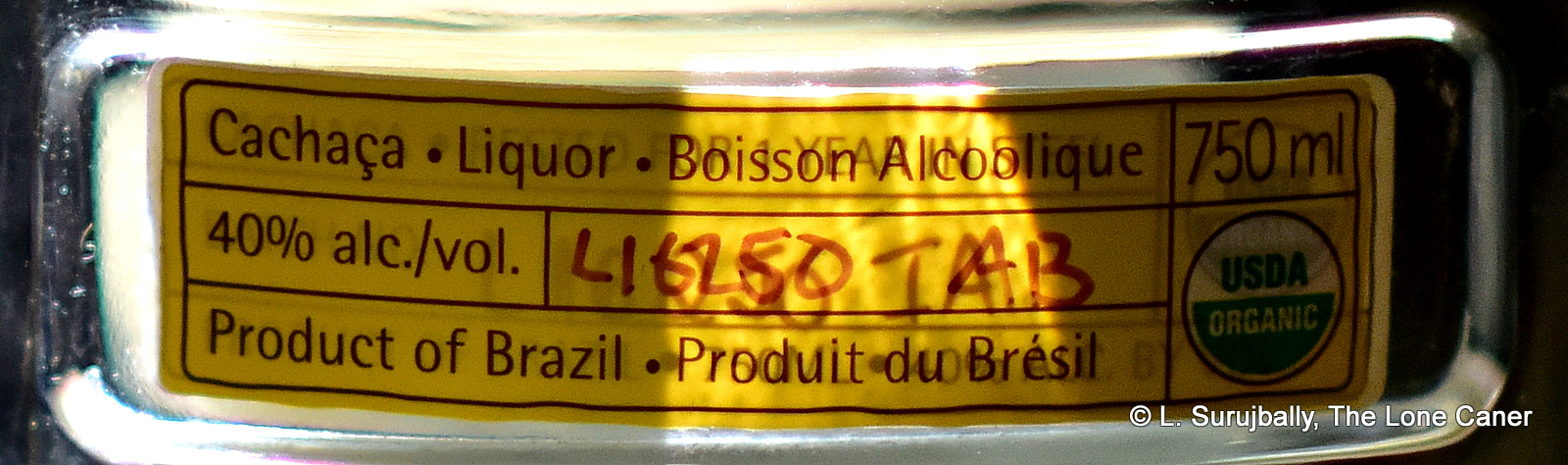

- Brazil, Epris Distillery, 10 YO (1999-2009), Chateau Lafite Finish (1400 bottles)

- Cuba, Sancti Spiritus Paraiso Distillery 11 YO (1998-2009) , Allegrini Amarone Finish (1800 bottles)

- Grenada, Westerhall Distillery, 12 YO (1996-2009), Chateau Margaux Finish (1600 bottles).

- Guadeloupe, Gardel Distillery, 11 YO (1998 – 2009), Chateau Latour finish (1300 bottles).

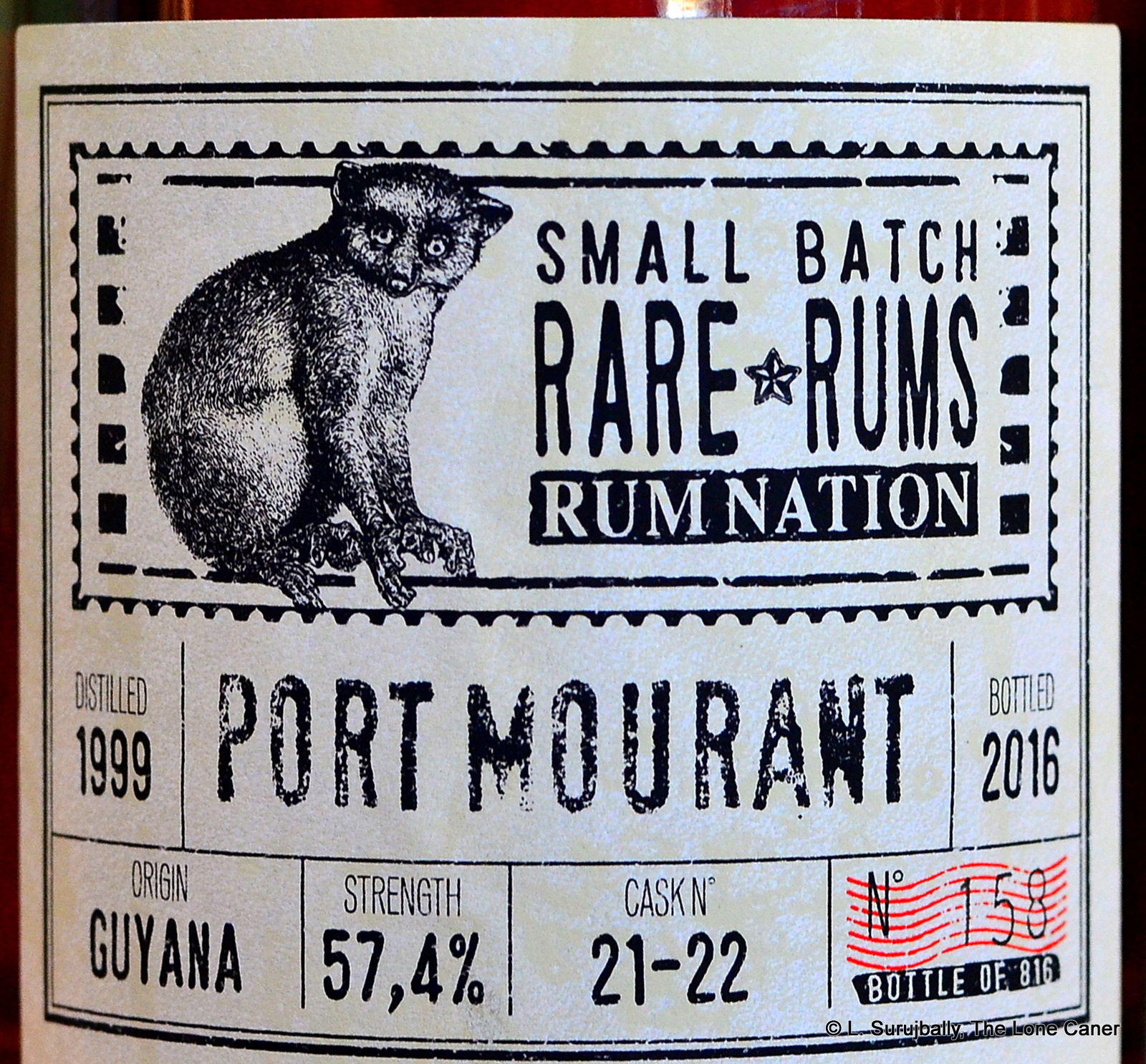

- Guyana, Port Mourant Distillery , 6 YO (2003-2009), Tempranillo Finish (6650 bottles)

- Jamaica, Monymusk Distillery, 5 YO (2003-2009), Tempranillo Finish (3960 bottles)

- Trinidad, Angostura Distillery, 17 YO (1991-2009), Chateau Le Pin Finish (1500 bottles)

- St. Lucia , St. Lucia Distillers, 10 YO (1999 – 2009), Chateau Lafleur Finish (1550 bottles)

2012

- Guyana, Diamond Distillery, 11 YO (2001 – 2012), Tempranillo finish (1800 bottles)

Murray McDavid bottlings of which I’m aware

References

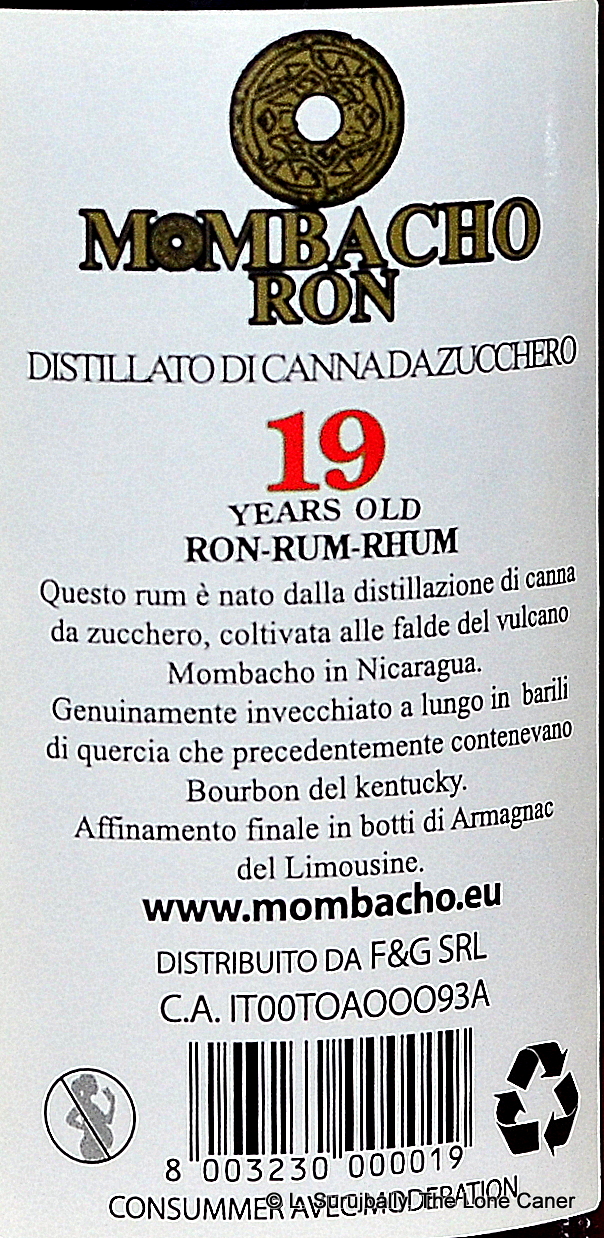

Herm. G. Dethleffsen, a German company, was established almost at the dawn of rum production itself, back in 1760 and had old and now (probably) long-forgotten brand names like Asmussen, Schmidt, Nissen, Andersen and Sonnberg in its portfolio, though what these actually were is problematic without much more research. What little I was able to unearth said Dethleffsen acquired other small companies in the region (some older than itself) and together made or distributed Admiral Vernon 54%, Jamaica Rum Verschnitt 40%, Nissen Rum-Verschnitt 38%, Old Schmidt 37.5%, this Ron White Cat 37.5% and a Ron White Cat Dark Rum Black Label, also at 37.5% – good luck finding any of these today, and even the dates of manufacture prove surprisingly elusive.

Herm. G. Dethleffsen, a German company, was established almost at the dawn of rum production itself, back in 1760 and had old and now (probably) long-forgotten brand names like Asmussen, Schmidt, Nissen, Andersen and Sonnberg in its portfolio, though what these actually were is problematic without much more research. What little I was able to unearth said Dethleffsen acquired other small companies in the region (some older than itself) and together made or distributed Admiral Vernon 54%, Jamaica Rum Verschnitt 40%, Nissen Rum-Verschnitt 38%, Old Schmidt 37.5%, this Ron White Cat 37.5% and a Ron White Cat Dark Rum Black Label, also at 37.5% – good luck finding any of these today, and even the dates of manufacture prove surprisingly elusive.