There are quite a few interesting (some would say strange) things about the Rhum Island / Island Cane brand, and the white rums in their portfolio. For one thing, the rhums are bottled in Saint Martin, only the second island in the Caribbean where two nations share a border – the Netherlands and France in this case, for both the constituent country of Sint Maarten (south side) and the Collectivité de Saint-Martin (north side) remain a part of the respective colonizing nations, who themselves don’t share a border anywhere else.

Secondly, there is neither a sugar or rum making industry on Saint Martin, which until 2007 was considered part of – and lumped in with – the overseas région and département of Guadeloupe: but by a popular vote it became a separate overseas Collectivité of France. Thirdly, the brand’s range is mostly multi-estate blends (not usual for agricoles), created, mixed and bottled in Saint Martin, and sources distillate from unnamed distilleries on Guadeloupe and Marie-Galante. And the two very helpful gents at the 2019 Paris Rhumfest booth — who kept filling my tasting glass and gently pressing me to try yet more, with sad, liquid eyes brimming with the best guilt trip ever laid on me — certainly weren’t telling me anything more than that.

That said, I can tell you that the rhum is a cane juice blanc, a blend whipped up from rhums from unnamed distilleries on Guadeloupe, created by a small company in St. Martin called Rhum Island which was founded in 2017 by Valerie Kleinhans, her husband and two partners; and supposedly conforms to all the regulations governing Guadeloupe rhum production (which is not the AOC, btw, but their own internal mechanism that’s close to it). Unfiltered, unaged, unadded to, and a thrumming 50% ABV. Single column still. Beyond that, it’s all about taste, and that was pretty damned fine.

I mean, admittedly the nose wasn’t anything particularly unique – it was a typical agricole – but it smelled completely delicious, every piece ticking along like a liquid swiss watch, precisely, clearly, harmoniously. It started off with crisp citrus and Fanta notes, and that evocative aroma of freshly cut wet grass in the sun. Also brine, red olives, cumin, dill, and the creaminess of a lemon meringue pie. There is almost no bite or clawing at the nose and while not precisely soft, it does present as cleanly firm.

Somewhat dissimilar thoughts attend the palate, which starts out similarly…to begin with. It’s all very cane-juice-y — sugar water, watermelons, cucumbers and gherkins in light vinegar that are boosted with a couple of pimentos for kick. This is all in a minor key, though – mostly it has a herbal sweetness to it, sap and spices, around which coils something extra…licorice, cinnamon, something musky, bordering on the occasionally excessive. The rhum, over time, develops an underlying solidity of the taste which is at odds with the clean delicacy of the nose, something pungent and meaty, and and everything comes to a close on the finish, which presents little that’s new – lemon zest, cane juice, sugar water, cucumbers, brine, sweet olives – but completely and professionally done.

This is a white rhum I really liked – while it lacked some of the clean precision and subtlety of the Martinique blanc rhums (even the very strong ones), it was quite original and, in its own way, even new…something undervalued in these times, I think. The initial aromas are impressive, though the muskier notes it displays as it opens up occasionally detract – in that sense I rate it as slightly less than the Island Rhum Red Cane 53% variation I tried alongside it…though no less memorable.

What’s really surprising, though, is how easy it is to drink multiple shots of this innocent looking, sweet-smelling, smooth-tasting white, while enjoying your conversation with those who nod, smile, and keep generously recharging your glass; and never notice how much you’ve had until you try to express your admiration for it by using the word “recrudescence” in a sentence, and fall flat on your face. But trust me, you’ll have a lot of fun doing it right up until then.

(#774)(84/100)

Other Notes

- The name of the company that makes it is Rhum Island — this doesn’t show on the label, only their website, so I’ve elected to call it as I saw it.

- This rhum was awarded a silver medal in the 2018 Concours Général Agricole de Paris

- Shortly after April 2019, the labels of the line were changed, and the bottle now looks as it does in the photo below. The major change is that the Rhum Island company name has more prominently replaced the “Island Cane” title

Photo provided courtesy of Rhum Island

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.

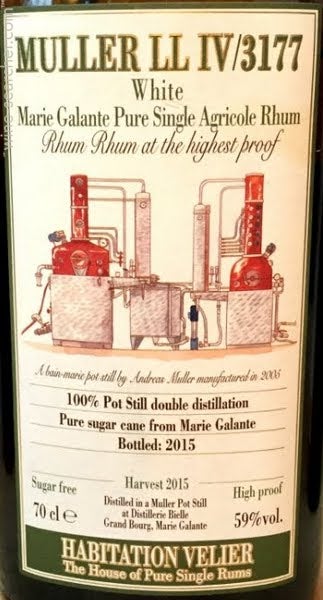

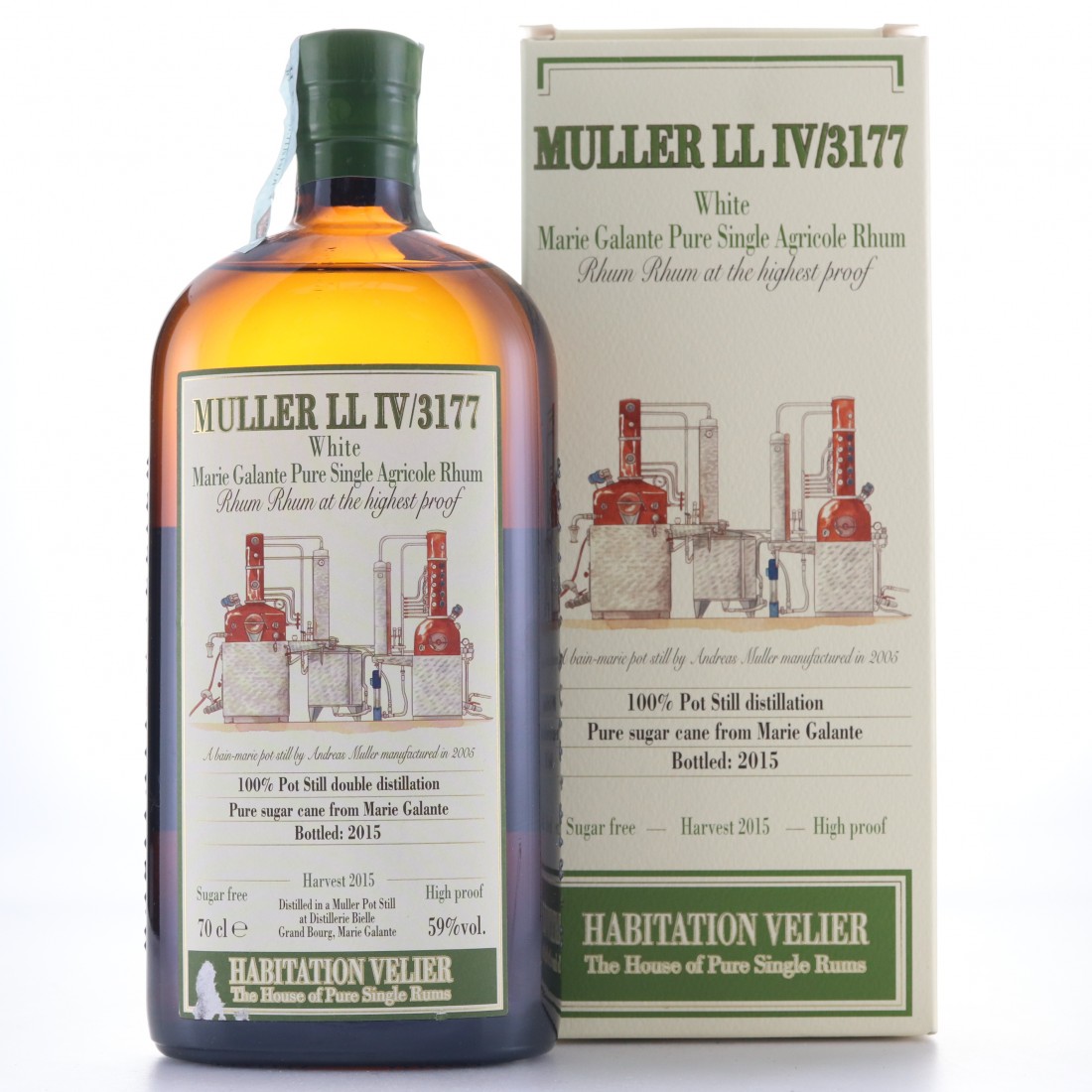

So let’s spare some time to look at this rather unique white rum released by Habitation Velier, one whose brown bottle is bolted to a near-dyslexia-inducing name only a rum geek or still-maker could possibly love. And let me tell you, unaged or not, it really is a monster truck of tastes and flavours and issued at precisely the right strength for what it attempts to do.

So let’s spare some time to look at this rather unique white rum released by Habitation Velier, one whose brown bottle is bolted to a near-dyslexia-inducing name only a rum geek or still-maker could possibly love. And let me tell you, unaged or not, it really is a monster truck of tastes and flavours and issued at precisely the right strength for what it attempts to do. Evaluating a rum like this requires some thinking, because there are both familiar and odd elements to the entire experience. It reminds me of

Evaluating a rum like this requires some thinking, because there are both familiar and odd elements to the entire experience. It reminds me of

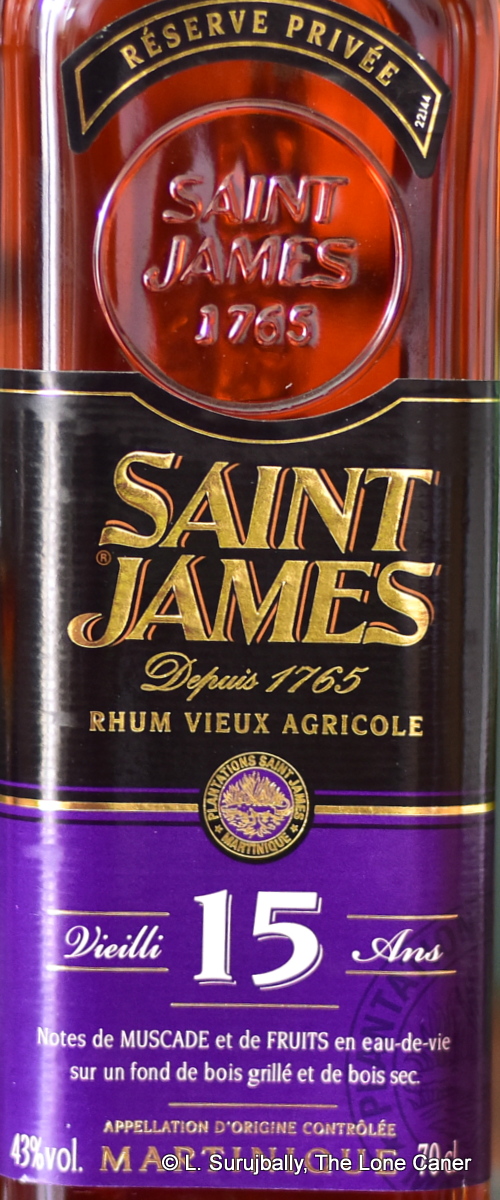

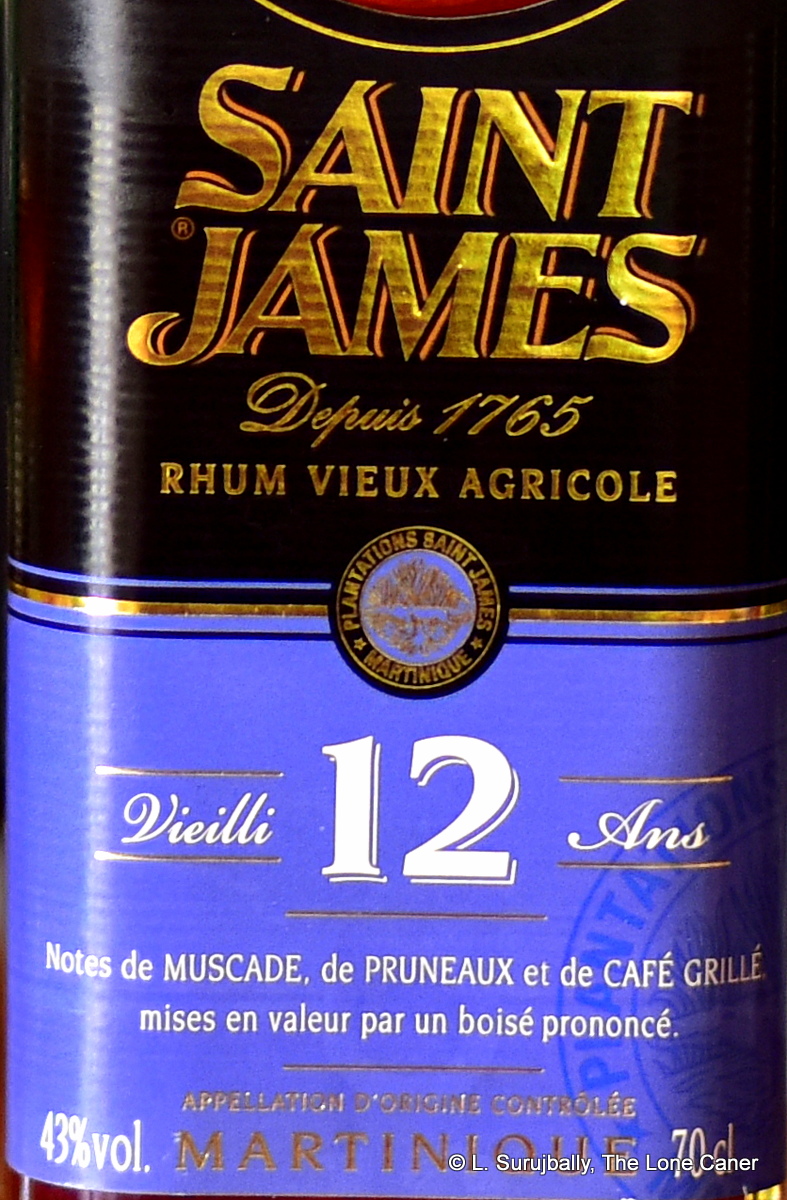

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

To some extent, it has a lighter nose than the luscious

To some extent, it has a lighter nose than the luscious

Colour – Amber

Colour – Amber

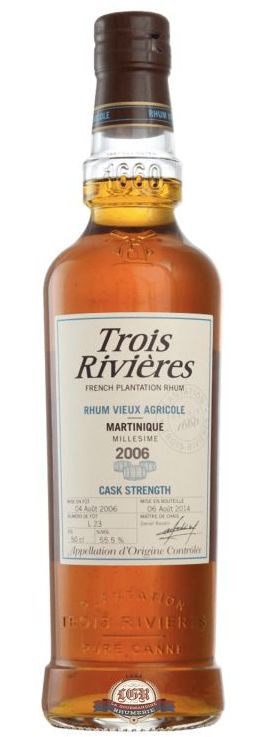

The Trois Rivières Brut de fût Millésime 2006 (which is its official name) is relatively unusual: it’s aged in new American oak barrels, not Limousin, and bottled at cask strength, not the more common 43-48%. And that gives it a solidity that elevates it somewhat over the standards we’ve become used to. Let’s start, as always, with the nose — it just becomes more assertive, and more clearly defined…although it seems somehow gentler (which is quite a neat trick when you think about it). It is redolent of caramel and vanilla first off, and then adds green apples, tart yoghurt, pears, white guavas, watermelon and papaya, and behind all that is a delectable series of herbs – rosemary, dill, even a hint of basil and aromatic pipe tobacco.

The Trois Rivières Brut de fût Millésime 2006 (which is its official name) is relatively unusual: it’s aged in new American oak barrels, not Limousin, and bottled at cask strength, not the more common 43-48%. And that gives it a solidity that elevates it somewhat over the standards we’ve become used to. Let’s start, as always, with the nose — it just becomes more assertive, and more clearly defined…although it seems somehow gentler (which is quite a neat trick when you think about it). It is redolent of caramel and vanilla first off, and then adds green apples, tart yoghurt, pears, white guavas, watermelon and papaya, and behind all that is a delectable series of herbs – rosemary, dill, even a hint of basil and aromatic pipe tobacco.

Okay so, on to palate. Straw yellow in the glass, it was softer and less intense, which, for a forty percenter, was both good and bad. Here the grassy and herbal notes took on more prominence, as did citrus, some tart unsweetened yoghurt, honey and cane juice. The youth was evident in the slight sharpness and lack of real roundness – the two years of ageing had

Okay so, on to palate. Straw yellow in the glass, it was softer and less intense, which, for a forty percenter, was both good and bad. Here the grassy and herbal notes took on more prominence, as did citrus, some tart unsweetened yoghurt, honey and cane juice. The youth was evident in the slight sharpness and lack of real roundness – the two years of ageing had  In 1923 La Mauny was sold to Théodore and Georges Bellonnie who enlarged and brought in new facilities such as a distillation column, new grinding mills and a steam engine. The distillery expanded hugely thanks to increased output and good marketing strategies and La Mauny rhums began to be exported around 1950. In 1970, after the Bellonnie brothers had both passed away, the Bordeaux traders and old-Martinique family of Bourdillon teamed up with Théodore Bellonnie’s widow and created the BBS Group. The company grew strongly, launching on the French market in 1977. Jean Pierre Bourdillon, who ran the new group, undertook to modernize La Mauny. He began by reorganizing the fields in order to make them accessible to mechanical harvesting and built a new distillery in 1984 (with a fourth mill, a three column still and a new boiler) a few hundred meters from the old one, increasing the cane crushing capacity and buying the equipment of the Saint James distillery in Acaiou, unused since 1958.

In 1923 La Mauny was sold to Théodore and Georges Bellonnie who enlarged and brought in new facilities such as a distillation column, new grinding mills and a steam engine. The distillery expanded hugely thanks to increased output and good marketing strategies and La Mauny rhums began to be exported around 1950. In 1970, after the Bellonnie brothers had both passed away, the Bordeaux traders and old-Martinique family of Bourdillon teamed up with Théodore Bellonnie’s widow and created the BBS Group. The company grew strongly, launching on the French market in 1977. Jean Pierre Bourdillon, who ran the new group, undertook to modernize La Mauny. He began by reorganizing the fields in order to make them accessible to mechanical harvesting and built a new distillery in 1984 (with a fourth mill, a three column still and a new boiler) a few hundred meters from the old one, increasing the cane crushing capacity and buying the equipment of the Saint James distillery in Acaiou, unused since 1958.

The full and rather unwieldy title of the rum today is the Chantal Comte Rhum Agricole 1975 Extra Vieux de la Plantation de la Montagne Pelée, but let that not dissuade you. Consider it a column-still, cane-juice rhum aged around eight years, sourced from Depaz when it was still André Depaz’s property and the man was – astoundingly enough in today’s market – having real difficulty selling his aged stock. Ms. Comte, who was born in Morocco but had strong Martinique familial connections, had interned in the wine world, and was also mentored by Depaz and Paul Hayot (of Clement) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Martinique was suffering from overstock and poor sales.. And having access at low cost to such ignored and unknown stocks allowed her to really pick some amazing rums, of this is one.

The full and rather unwieldy title of the rum today is the Chantal Comte Rhum Agricole 1975 Extra Vieux de la Plantation de la Montagne Pelée, but let that not dissuade you. Consider it a column-still, cane-juice rhum aged around eight years, sourced from Depaz when it was still André Depaz’s property and the man was – astoundingly enough in today’s market – having real difficulty selling his aged stock. Ms. Comte, who was born in Morocco but had strong Martinique familial connections, had interned in the wine world, and was also mentored by Depaz and Paul Hayot (of Clement) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Martinique was suffering from overstock and poor sales.. And having access at low cost to such ignored and unknown stocks allowed her to really pick some amazing rums, of this is one.

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

Unlike many aged agricoles that have run into my glass (and down my chin), I found this one to be quite sweet, and for all the solidity of the strength, also rather scrawny, a tad sharp. At least at the beginning, because once a drop of water was added and I chilled out a few minutes, it settled down and it tasted softer, earthier, muskier. Creamy salt butter on black bread, sour cream, yoghurt, and also fried bananas, pineapple, anise, lemon zest, cumin, raisins, green grapes, and a few more background fruits and florals, though these never come forward in any serious way. The finish is excellent, by the way – some vague molasses, burnt sugar, the creaminess of hummus and olive oil, caramel, flowers, apples and some tart notes of soursop and yellow mangoes and maybe a gooseberry or two. Nice.

Unlike many aged agricoles that have run into my glass (and down my chin), I found this one to be quite sweet, and for all the solidity of the strength, also rather scrawny, a tad sharp. At least at the beginning, because once a drop of water was added and I chilled out a few minutes, it settled down and it tasted softer, earthier, muskier. Creamy salt butter on black bread, sour cream, yoghurt, and also fried bananas, pineapple, anise, lemon zest, cumin, raisins, green grapes, and a few more background fruits and florals, though these never come forward in any serious way. The finish is excellent, by the way – some vague molasses, burnt sugar, the creaminess of hummus and olive oil, caramel, flowers, apples and some tart notes of soursop and yellow mangoes and maybe a gooseberry or two. Nice.

Anyway, here’s what it was like. The nose of the Ilha da Madeira fell somewhere in the middle of the line separating a bored “meh” from a more disbelieving “holy-crap!”. It was a light melange of a playful sprite-like aroma mixed in with more serious brine and olives, a little sweet, and delicate – flowers, sugar water, grass, pears, guavas, mint, some marzipan. You could sense something darker underneath – cigarette tar, acetones – but these never came forward, and were content to be hinted at, not driven home with a sledge. Not really a brother to that fierce Jamaican brawler, more like a cousin, a closer relative to the

Anyway, here’s what it was like. The nose of the Ilha da Madeira fell somewhere in the middle of the line separating a bored “meh” from a more disbelieving “holy-crap!”. It was a light melange of a playful sprite-like aroma mixed in with more serious brine and olives, a little sweet, and delicate – flowers, sugar water, grass, pears, guavas, mint, some marzipan. You could sense something darker underneath – cigarette tar, acetones – but these never came forward, and were content to be hinted at, not driven home with a sledge. Not really a brother to that fierce Jamaican brawler, more like a cousin, a closer relative to the

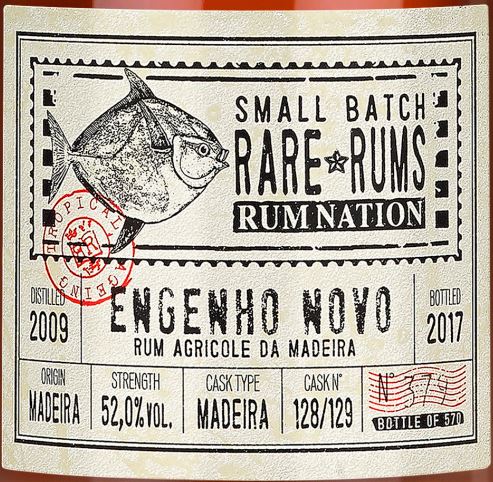

I’ll provide some more background detail in the Other Notes below, but for the moment let’s just read off the fact sheet for the rum which is very helpfully provided on the Rare Rums website and on the bottle label itself. This is a cane juice distillate and can therefore be classed as an agricole-style rhum; distilled 2009 and the four barrel outturn from a column still was aged in Madeira casks, providing 570 bottles in 2017, with a strength of 52%.

I’ll provide some more background detail in the Other Notes below, but for the moment let’s just read off the fact sheet for the rum which is very helpfully provided on the Rare Rums website and on the bottle label itself. This is a cane juice distillate and can therefore be classed as an agricole-style rhum; distilled 2009 and the four barrel outturn from a column still was aged in Madeira casks, providing 570 bottles in 2017, with a strength of 52%.

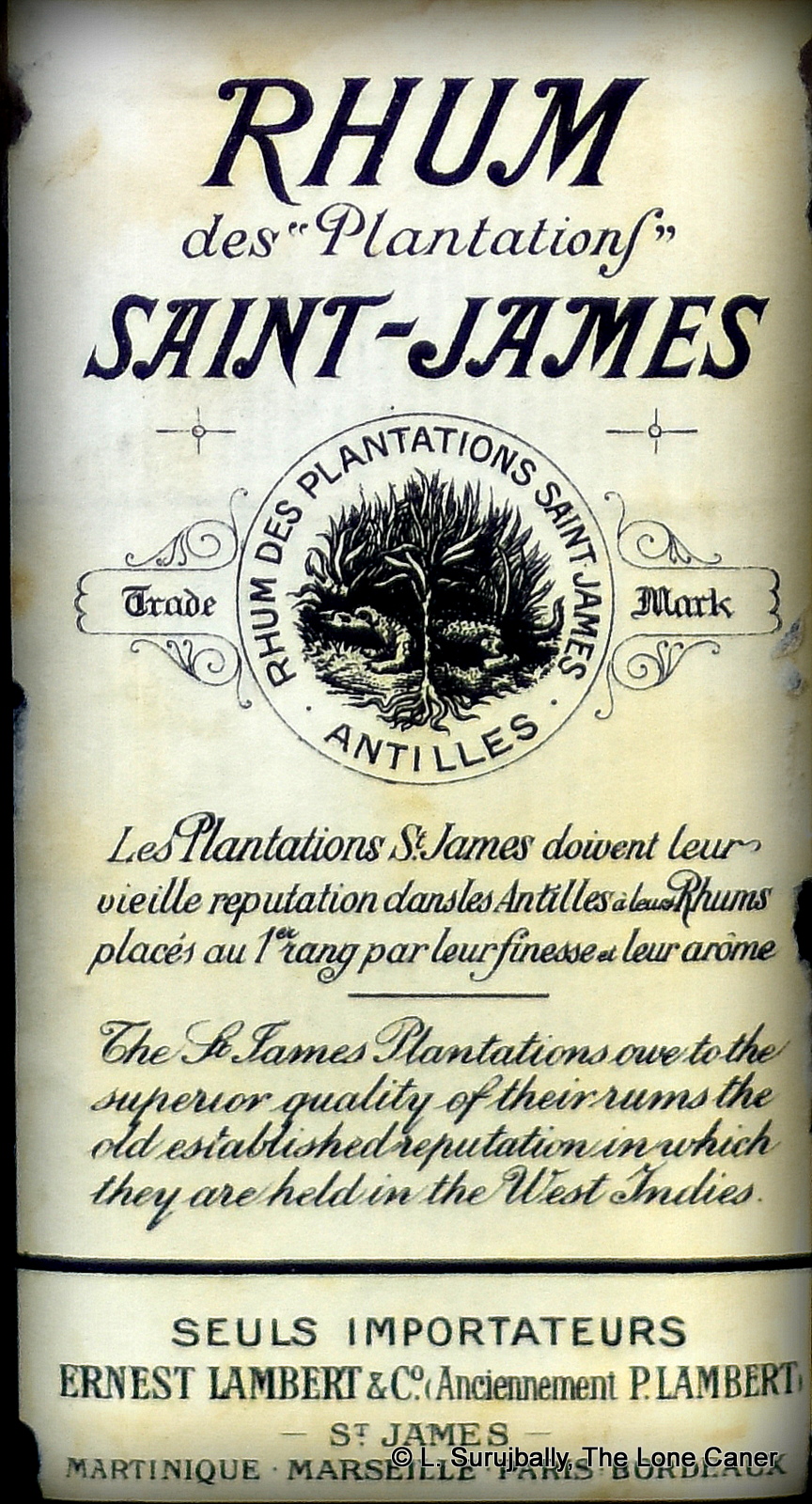

Still, we had to get facts, and a lot of our preliminary conversations and subsequent texts and messages revolved around the data points, which are as follows: the rhum was made in 1885 on Martinique, and derived from cane juice that was boiled prior to fermentation. Although the exact age is unknown, it was certainly shipped off the island before Mount Pelée erupted in 1902 and destroyed all stocks there, so at an absolute maximum it can be 17 years old. This is, however unlikely – few rums or rhums were aged that long back then, and the opinion of the master blender of St James (Mark Sassier) that it was 8-10 years old is probably the best one (

Still, we had to get facts, and a lot of our preliminary conversations and subsequent texts and messages revolved around the data points, which are as follows: the rhum was made in 1885 on Martinique, and derived from cane juice that was boiled prior to fermentation. Although the exact age is unknown, it was certainly shipped off the island before Mount Pelée erupted in 1902 and destroyed all stocks there, so at an absolute maximum it can be 17 years old. This is, however unlikely – few rums or rhums were aged that long back then, and the opinion of the master blender of St James (Mark Sassier) that it was 8-10 years old is probably the best one (