Rumaniacs Review #109 | 0696

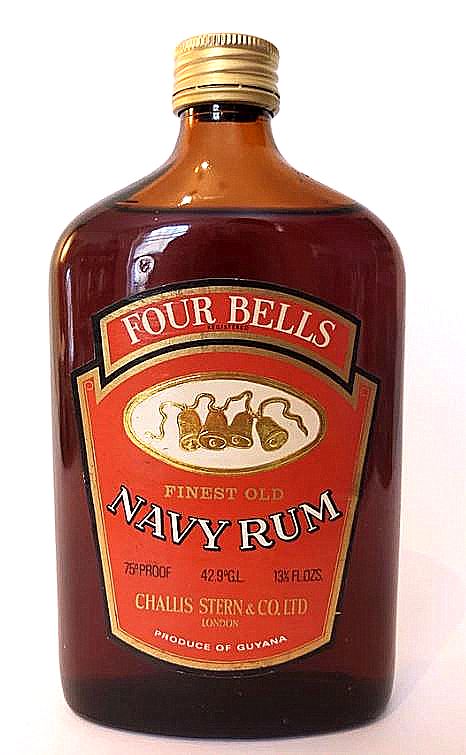

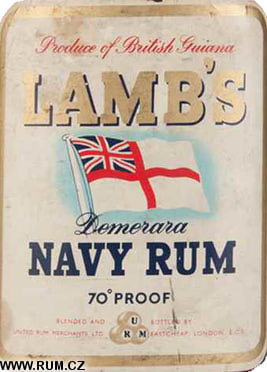

It may be called a Navy rum but the label is quite clear that it’s a “Product of Guyana” so perhaps what they were doing is channelling the Pussers rums from forty years later, which also and similarly restricted themselves to one component of the navy rum recipe. The British maritime moniker has always been a rather plastic concept – as an example, I recall reading that they also sourced rums from Australia for their blend at one point – so perhaps, as long as it was sold and served to the Navy, it was allowed the title. Or maybe it’s just canny marketing of an un-trademarked title, which is meant to describe a style of rum as it was commonly understood back then.

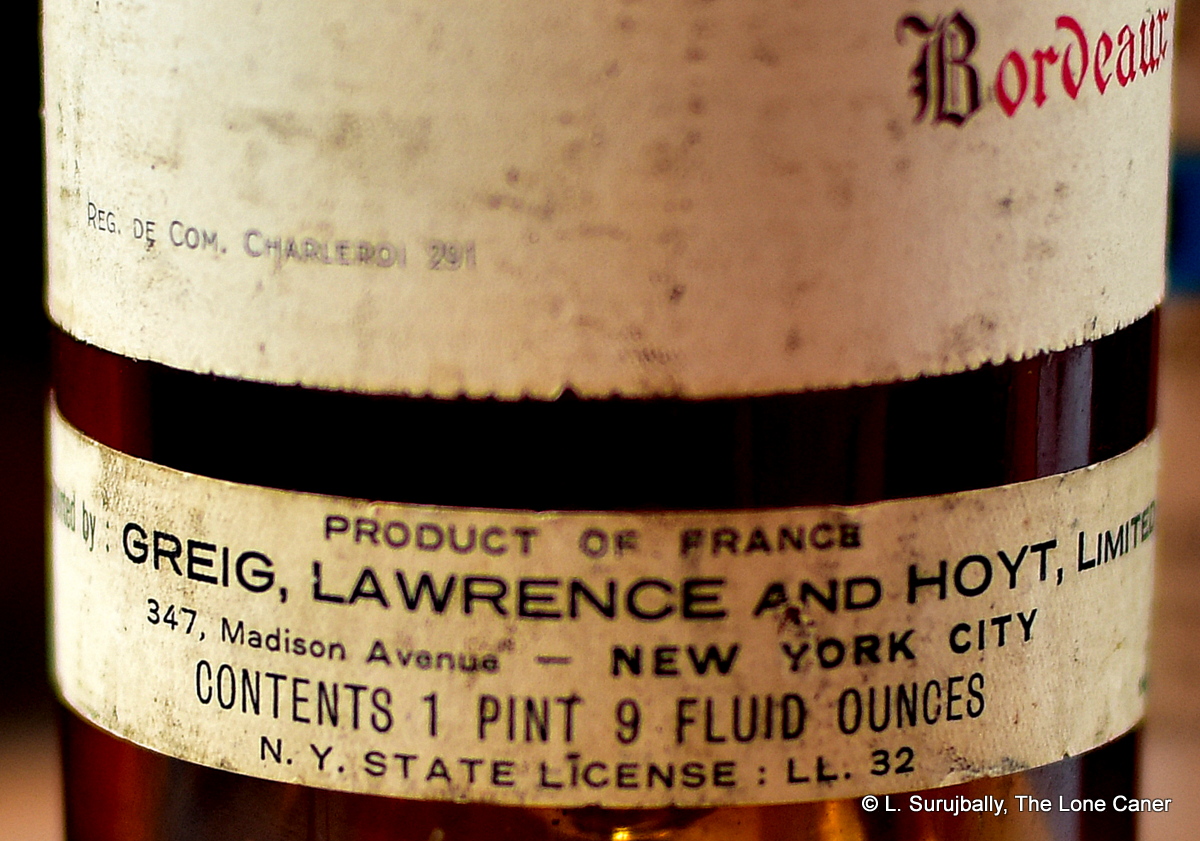

It’s unclear when this particular rum was first introduced, as references are (unsurprisingly) scarce. It was certainly available during the 1970s, which is the earliest to which I’ve managed to date this specific bottle based on label inclusions. One gentleman commented on the FRP’s review “This was the Rum issued to all ships up until the demise of the Merchant Navy (British Merchant Marine) in 1987. We didn’t receive a tot of rum like the Royal Navy, instead we had our own-run bars (officers’ bar, crew bar). The label with the bells was changed sometime in the early/mid 80’s to a brown coloured label with a sailing ship.” Based on some auction listings I’ve seen, there are several different variations of the label, but I think it is safe to say that this red one dates back from the late 1970s, early 1980s at the latest.

An older label: note the HMS Challis under the bells, which I was unable to trace

Challis, Stern & Co. was a spirits wholesaler out of London that was incorporated back in 1924 – like many other small companies we have met in these reviews, they dabbled in occasional bottlings of rum to round out their wholsesaling business, and were making Four Bells rum since the 1960s at least (I saw a label on Pete’s Rum Pages with “product of British Guiana” on the label, as well as a white from post-independence times), and in all cases they used exclusively Guyanese stock. There are glancing references to an evolution of the rum in the 1980s primarily based on how the labels looked and the auctioneers’ info listings – but it seems clear that by then it was in trouble as it ceased trading in 1989 and were taken over in 1991 by the Jackson family who run wine dealers Jackson Nugent Vintners, and they then wrapped it up without fuss or fanfare in 2006 (Challis had been classified as “dormant” for their entire tenure). It remains unclear why they bothered acquiring it unless it was to gain control of some tangible or intangible asset in which they were interested (I have an email to them to check).

Colour – Amber

Strength – 42.9% (75 proof old-style)

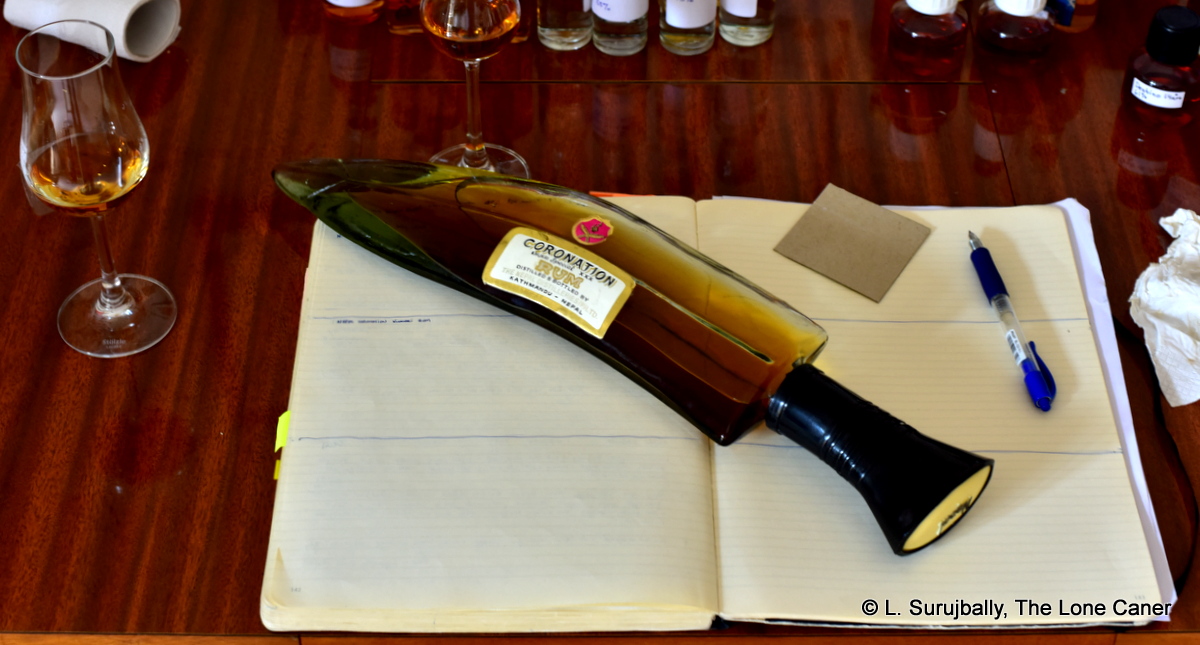

A “half” of Four Bells, what Guyanese would call a “flattie”. Fits nicely into a hip pocket

Nose – Quite definitely a Guyanese rum, though with odd bits here and there. Caramel, salt, butter, rye or sourdough bread with a touch of molasses and anise and flowers and fruits, none of which is very dominant. Prunes, dates, overripe cherries and the musky softness of fried bananas. Also pencil shavings and sawdust at the back end.

Palate – Dry, with a most peculiar aroma of sweet rubber. I know how that sounds, but I like it anyway, because there was a certain richness to the whole experience. Sweet red wine notes, backed up with caramel, dark chocolate, nougat and nuts. Quite a solid texture on the tongue, slightly sweet and rounded and without any bitterness of oak (the age is unknown).

Finish – Short and dry, but enjoyable. Mostly caramel, toffee, sawdust and pencil shavings,

If I had to guess, I’d say this was an Enmore or the French Savalle still. Be that as it may, it goes up well against modern standard-strength DDL rums because it presents as very restrained and toned down, without every losing sight of the fact that it’s a rum. Nowadays of course, you can only get a bottle from old salts, old cellars, grandfathers or auctions, but if you find one, it’s not a bad buy.

(81/100)

Other Notes

- Taken literally, the “four bells” name is an interesting one. In British Navy tradition, the strikes of a ship’s bell were not aligned with the hour. Instead, there were eight bells, one for each half-hour of a four-hour watch – four bells is therefore halfway through any one of the Middle, Morning, Forenoon, Afternoon, Dog or First watches (good that someone knew this, because eight bells would have been an unfortunate term to use for a rum, being used as it was to denote end of watch” or a funeral). All that said, the design of the four bells on the label could equally be representative of four founders, or be something more festive, so maybe this whole paragraph is an aside that indulges my love of historical background.

- Proof and ABV – In 1969 the UK government created the Metrication Board to promote and establish metrification in Britain, generally on a voluntary basis. In 1978 government policy shifted, and they made it mandatory in certain sectors. In 1980 that policy flip-flopped again to revert to a voluntary basis, and the Board was abolished, though by this date just about all rum labels had ABV and the proof system fell into disuse – and essentially, this allows dating of UK labels to be done within some broad ranges.

Nose – Quite a bit different from the strongly focussed Demerara profile of the Navy 70º we looked at before – had the label not been clear what was in it, I would have not guessed there was any Jamaican in here. The wooden stills profile of Guyana is tamed, and the aromas are prunes, licorice, black grapes and a light brininess. After a while some salt caramel ice cream, nougat, toffee and anise become more evident. Sharp fruits are held way back and given the absence of any kind of tarriness, I’d hazard that Angostura provided the Trinidadian component.

Nose – Quite a bit different from the strongly focussed Demerara profile of the Navy 70º we looked at before – had the label not been clear what was in it, I would have not guessed there was any Jamaican in here. The wooden stills profile of Guyana is tamed, and the aromas are prunes, licorice, black grapes and a light brininess. After a while some salt caramel ice cream, nougat, toffee and anise become more evident. Sharp fruits are held way back and given the absence of any kind of tarriness, I’d hazard that Angostura provided the Trinidadian component.  Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688

Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688 Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

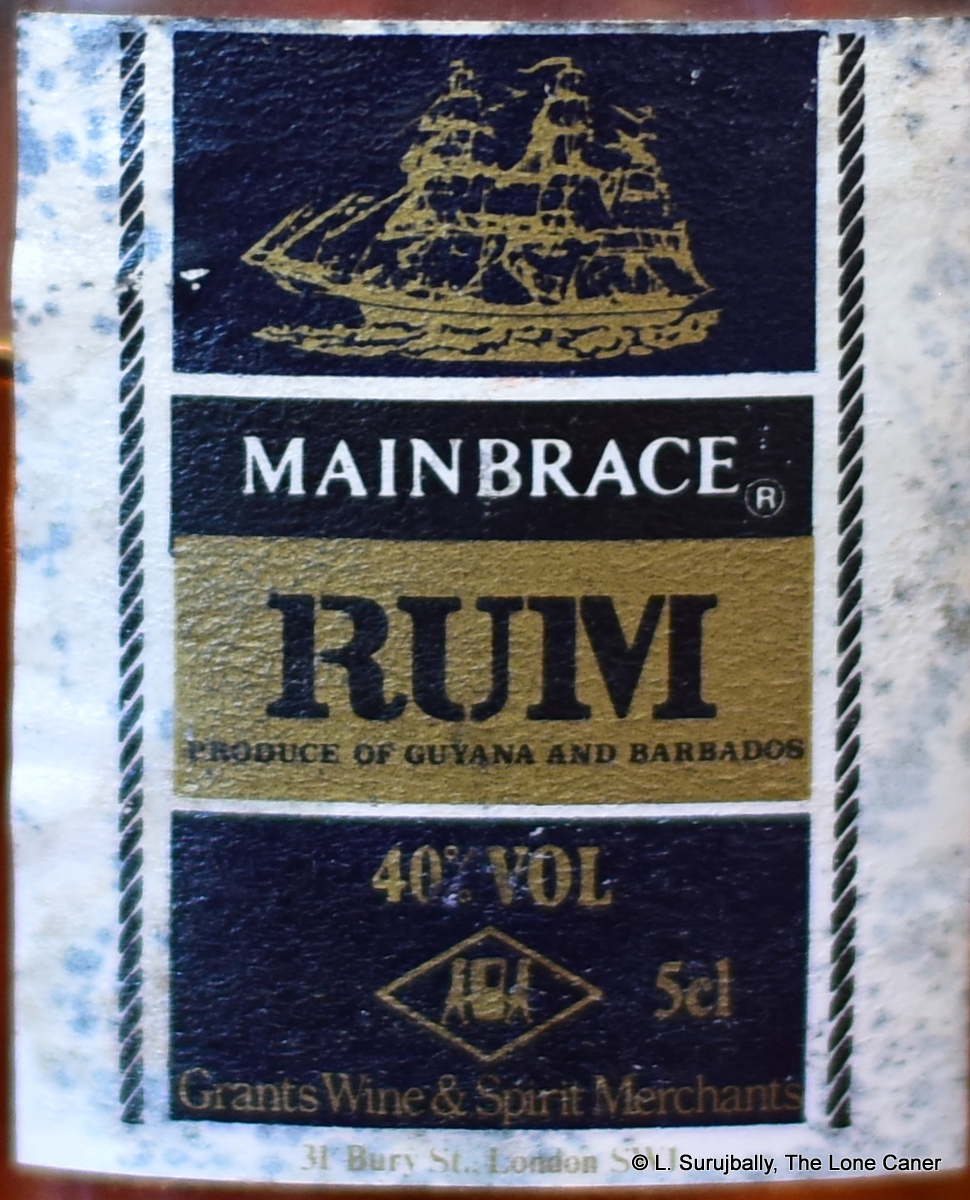

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.  Rumaniacs Review #105 | 0678

Rumaniacs Review #105 | 0678 Nose – A combination of the

Nose – A combination of the  Rumaniacs Review #104 | 0677

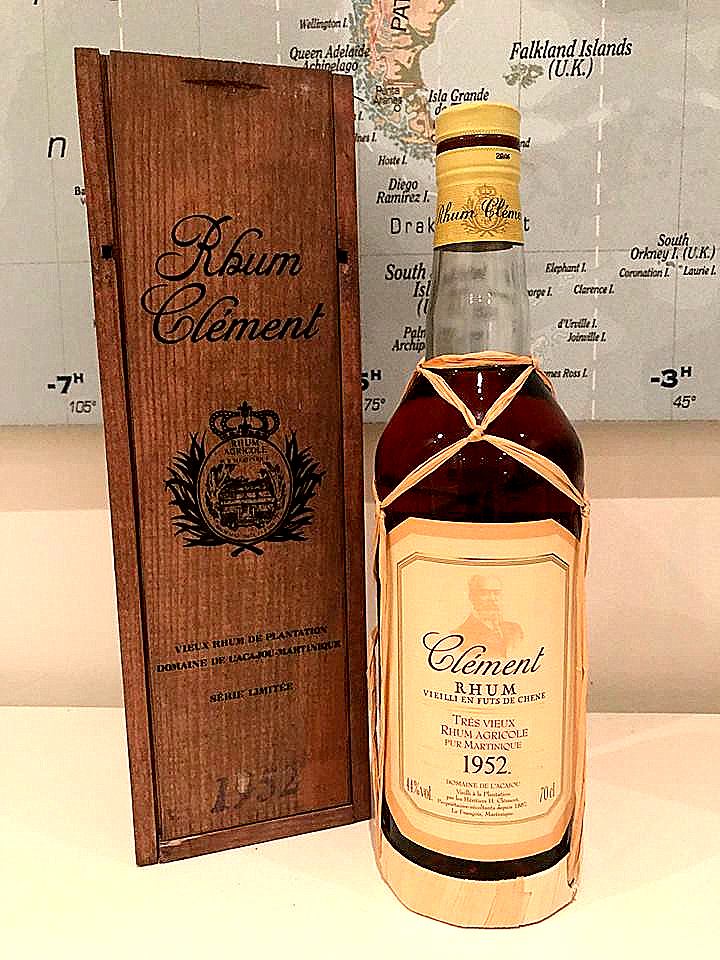

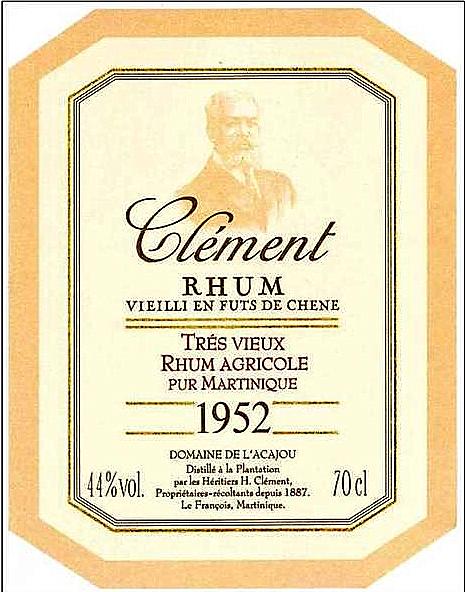

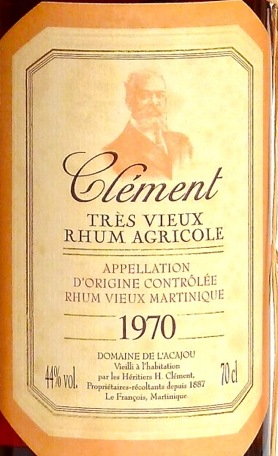

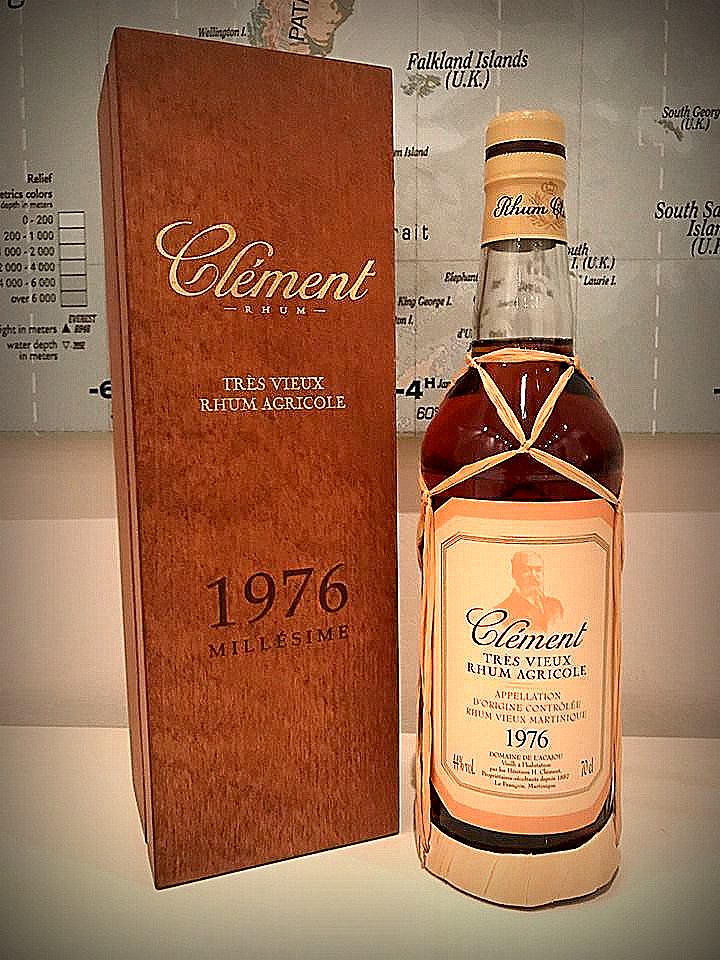

Rumaniacs Review #104 | 0677 Another peculiarity of the rhum is the “AOC” on the label. Since the AOC came into effect only in 1996, and even at its oldest this rhum was done ageing in 1991, how did that happen? Cyril told me it had been validated by the AOC after it was finalized, which makes sense (and probably applies to the 1976 edition as well), but then, was there a pre-1996 edition with one label and a post-1996 edition with another one? (the two different boxes it comes in suggests the possibility). Or, was the entire 1970 vintage aged to 1991, then held in inert containers (or bottled) and left to gather dust for some reason? Is either 1991 or 1985 even real? — after all, it’s entirely possible that the trio (of 1976, 1970 and 1952, whose labels are all alike) was released as a special millesime series in the late 1990s / early 2000s. Which brings us back to the original question – how old is the rhum?

Another peculiarity of the rhum is the “AOC” on the label. Since the AOC came into effect only in 1996, and even at its oldest this rhum was done ageing in 1991, how did that happen? Cyril told me it had been validated by the AOC after it was finalized, which makes sense (and probably applies to the 1976 edition as well), but then, was there a pre-1996 edition with one label and a post-1996 edition with another one? (the two different boxes it comes in suggests the possibility). Or, was the entire 1970 vintage aged to 1991, then held in inert containers (or bottled) and left to gather dust for some reason? Is either 1991 or 1985 even real? — after all, it’s entirely possible that the trio (of 1976, 1970 and 1952, whose labels are all alike) was released as a special millesime series in the late 1990s / early 2000s. Which brings us back to the original question – how old is the rhum? Rumaniacs Review #103 | 0676

Rumaniacs Review #103 | 0676

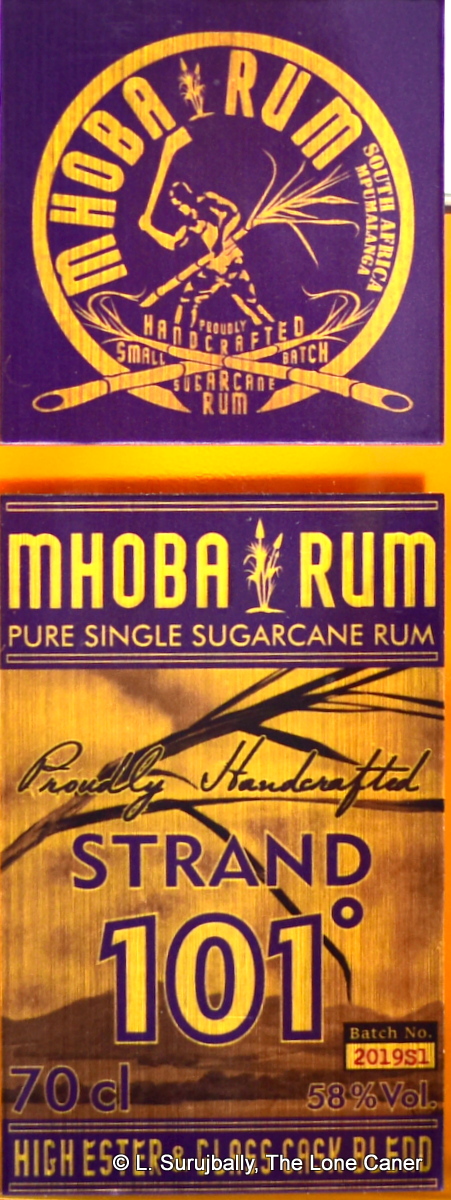

The Strand 101° was specifically designed by Knud Strand, a colourful Danish distributor who worked closely with Robert Greaves (as he had with many brands before) to bring the Mhoba line to market. What he was looking for was to create a blend of unaged and aged rum from pot stills, adhering to something of the S&C profile but from only one still (not two or more). He was messing around with samples some time back and after making his selections finally came back to two, both fullproof — one, slightly aged was too woody, with the other unaged one perhaps too funky.

The Strand 101° was specifically designed by Knud Strand, a colourful Danish distributor who worked closely with Robert Greaves (as he had with many brands before) to bring the Mhoba line to market. What he was looking for was to create a blend of unaged and aged rum from pot stills, adhering to something of the S&C profile but from only one still (not two or more). He was messing around with samples some time back and after making his selections finally came back to two, both fullproof — one, slightly aged was too woody, with the other unaged one perhaps too funky.

This bottle likely comes from the late 1970s: there is an earlier version noted as being from “British Guiana” that must have dated from the 1960s (Guyana gained independence in 1966) and by 1980 the UK largely ceased using degrees proof as a unit of alcoholic measure; and United Rum Merchants was taken over in 1984, which sets an absolute upper limit on its provenance (the URM is represented by the three barrels signifying Portal Dingwall & Norris, Whyte-Keeling and Alfred Lamb who merged in 1948 to form the company). Note also the “Product of Guyana” – the original blend of 18 different rums from Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad pioneered by Alfred Lamb, seems to have been reduced to Guyana only for the purpose of releasing this one.

This bottle likely comes from the late 1970s: there is an earlier version noted as being from “British Guiana” that must have dated from the 1960s (Guyana gained independence in 1966) and by 1980 the UK largely ceased using degrees proof as a unit of alcoholic measure; and United Rum Merchants was taken over in 1984, which sets an absolute upper limit on its provenance (the URM is represented by the three barrels signifying Portal Dingwall & Norris, Whyte-Keeling and Alfred Lamb who merged in 1948 to form the company). Note also the “Product of Guyana” – the original blend of 18 different rums from Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad pioneered by Alfred Lamb, seems to have been reduced to Guyana only for the purpose of releasing this one.

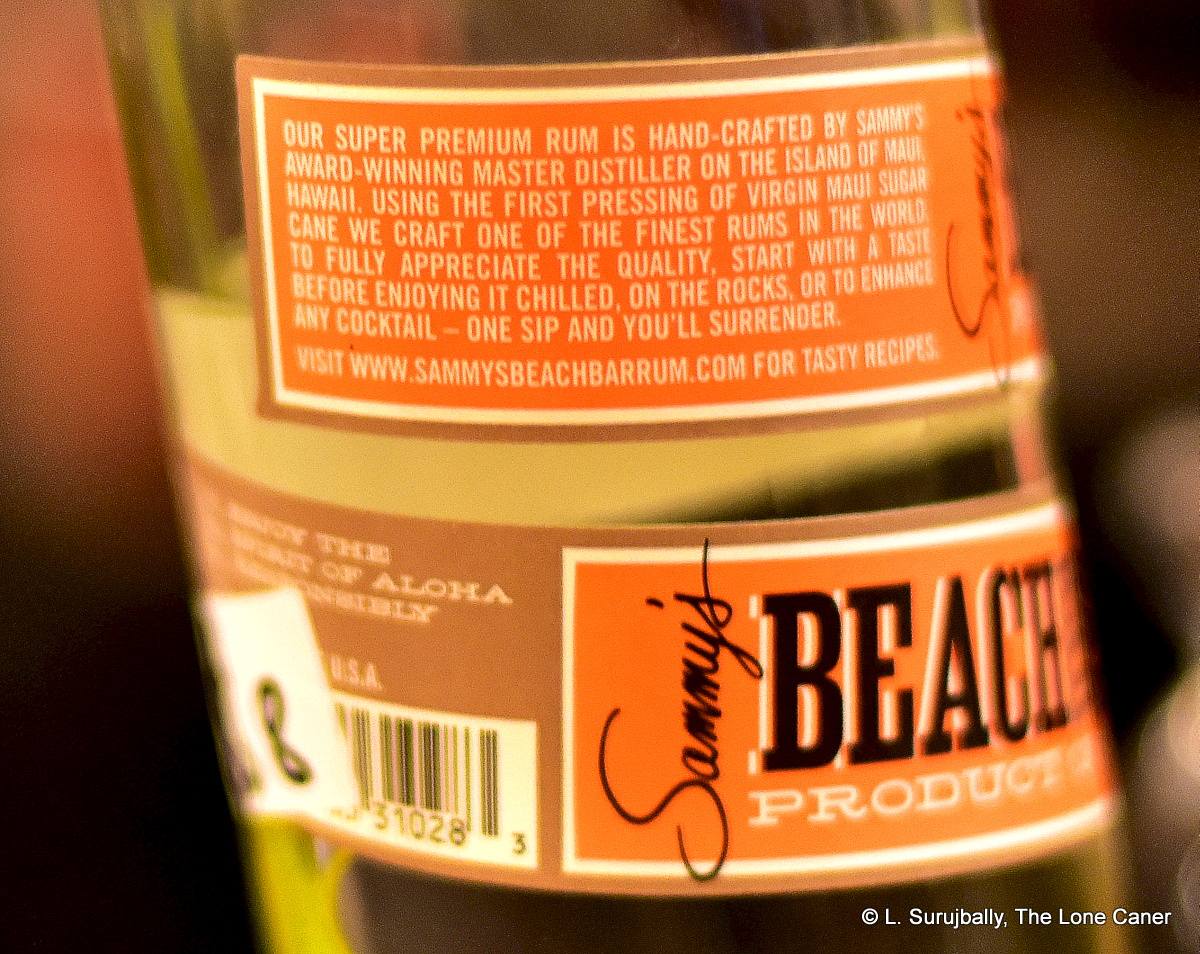

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the  With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

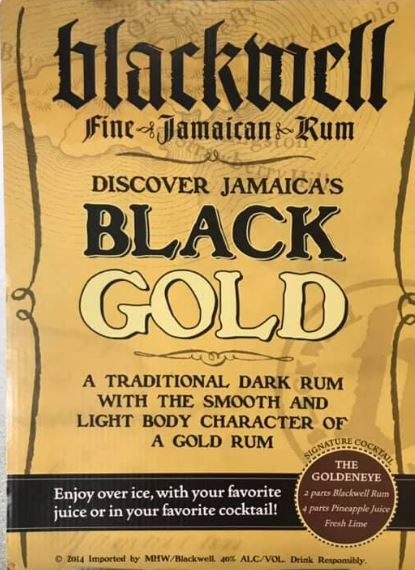

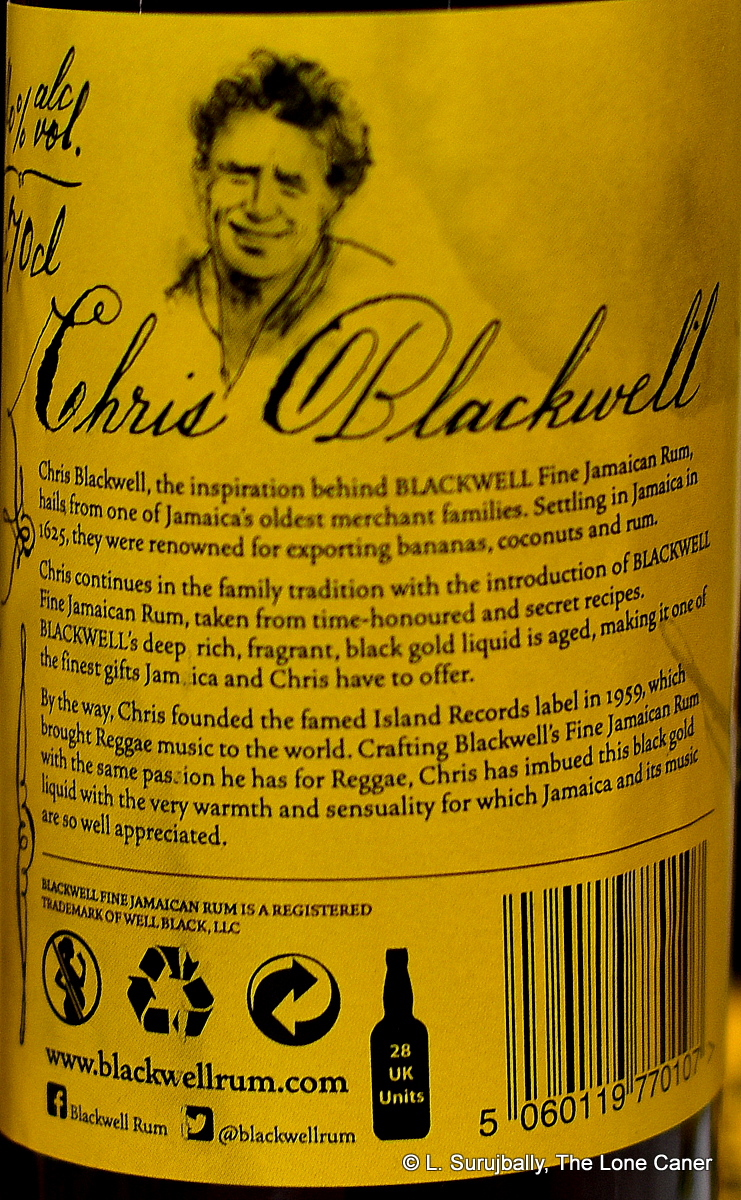

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in  With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?