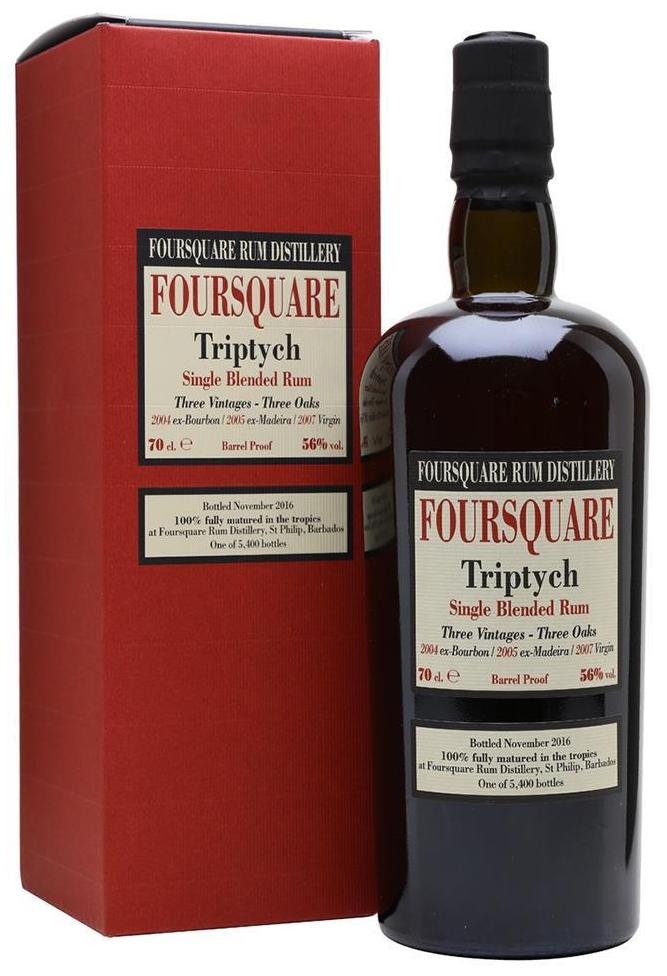

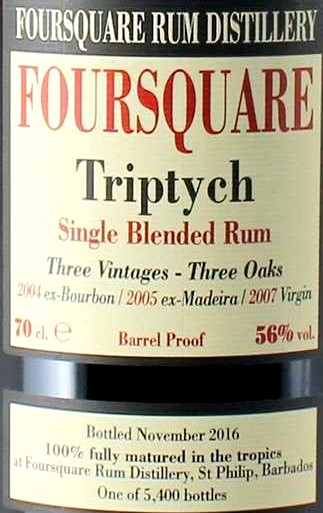

In my more whimsical moments, I like to think Richard Seale was sweating a bit as he prepared the Triptych. Bottled in November 2016 and released in the 2017 season, it came right on the heels of the hugely successful and awe-inducing unicorn of the 2006 10 Year Old which had almost immediately ascended to near cult status and stayed there ever since. How could any follow-up match that? It was like coming up on stage after Mighty Liar just finished belting out “She Want Pan” hoping at least not too suck too bad in comparison. He need not have worried — the Triptych flew off the shelves every bit as fast as its predecessor (much to his relief, I’m sure), though in the years that followed people never quite mentioned it in the same hushed tones, with the same awe, and with the same whimpers of regret, as they did the 2006. Some, yes…but not to the same extent.

That may just be a little unfair though, because the Triptych is an enormously satisfying rum, another one of the limited “Collaboration” series between Foursquare and Velier 1 that are notable for their visually elegant simplistic design, their full proof strength and their polysyllabic titles which may have reached their apogee with the Plenipotenziario (while there’s usually a stated rationale behind the choice, I’ve always suspected were a tongue-in-cheek wink at all of us, a sort of private thing between the two men behind it).

It is also a rum that was made to deliberately showcase other aspects of the way a pot-column blend could be made to shine. Some call it “innovation” but honestly, I think the word is tossed around a bit too cavalierly these days, so let’s just say there’s always another way to blend various aged components, and Foursquare are acknowledged masters of the craft. Most blends are various aged rums, harmoniously mixed together: here, three differently aged elements, or ‘sub-blends’, were joined in a combination – a triptych, get it? – that could be appreciated as balanced synthesis of all.

It is also a rum that was made to deliberately showcase other aspects of the way a pot-column blend could be made to shine. Some call it “innovation” but honestly, I think the word is tossed around a bit too cavalierly these days, so let’s just say there’s always another way to blend various aged components, and Foursquare are acknowledged masters of the craft. Most blends are various aged rums, harmoniously mixed together: here, three differently aged elements, or ‘sub-blends’, were joined in a combination – a triptych, get it? – that could be appreciated as balanced synthesis of all.

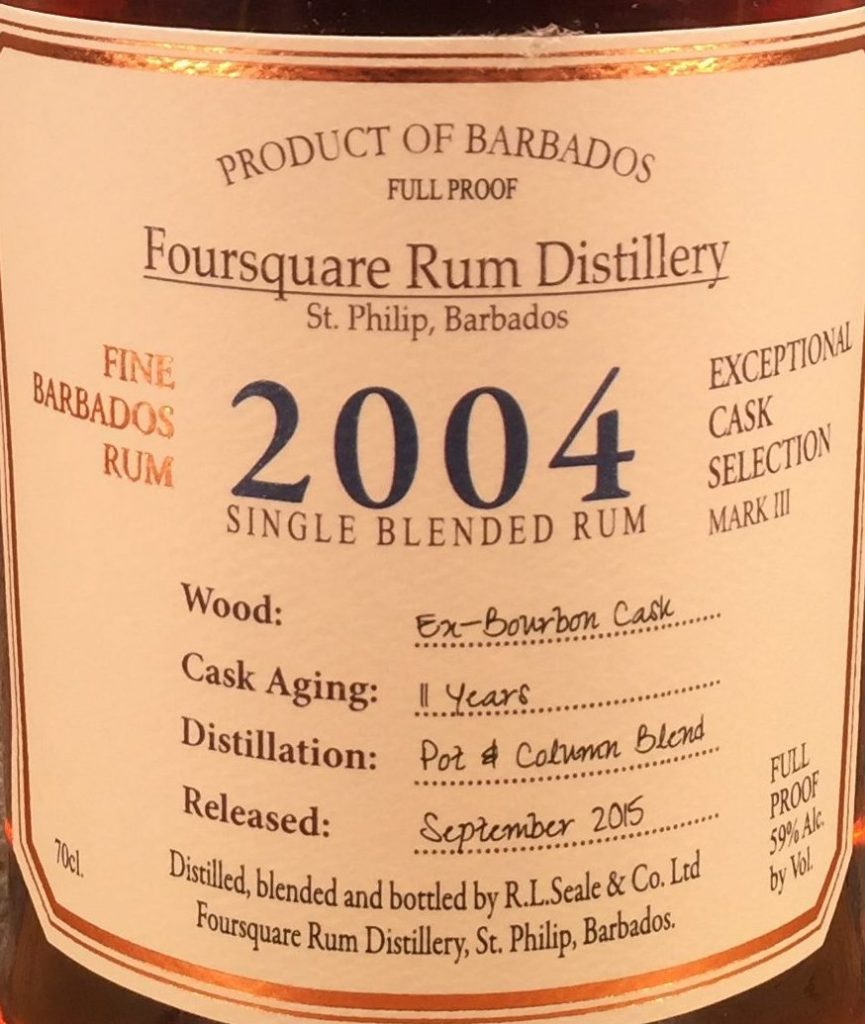

These three pieces were [1] a 2004 pot-column blend matured in ex-Bourbon casks [2] a 2005 pot-column blend aged in ex-Madeira and [3] a 2007 pot-column blend matured in brand new (‘virgin’) oak casks. The actual duration of ageing of each before they were blended and then transferred to the final casks for completion of the blending and ageing process, is not known, though Steve James, who has what is probably the most comprehensive background notes on the Triptych, notes that the component aged in virgin oak was aged for six years before transfer (six months is more common due to the active nature of the wood, which in this instance also necessitated a larger proportion of pot still distillate of the blend in these casks).

Clearly this made for a very complex blend of disparate profiles, any one of which could unbalance the whole: the musky, darker notes of the bourbon, the dry sweet acidity of Madeira and the aggressive woody characteristic of new oak casks. At the risk of a spoiler, the rum mostly sailed past these concerns. Nosing it experimentally at first, I was struck by how delicately perfumed it was, quite dry, rather mildly fruity and much more restrained than the solid weight of the Principia that lurked in the glass alongside – this was probably a consequence of the lesser-but-still-solid proof point of 56% ABV. The fruits stayed in the background for most of the experience, and the dominant aspect of the nose was a remarkably restrained woodiness – mild pencil shavings, vanilla, musty books, old cardboard, charcoal, and damp mossy forest floors in the morning. There were also hints of crushed walnuts, almonds and spices like marsala, cumin and rosemary, plus coconut shavings, flambeed bananas and overripe peaches, but these stayed well back throughout.

The rum came into its own on the palate, where even with its relatively few core flavours, it surged to the front with an assurance that proved you don’t need a 99-piece orchestra to play Vivaldi. The rum was thick, rich and – dare we say it? – elegant: it tasted of blood oranges, coconut milk, honey, vanilla and cinnamon on the one hand, and brine, floor polish, cigarette ash (yes, I know how that sounds) on the other, and in the middle there was some sweet sour elements of sauerkraut, licorice, pickles and almonds, all tied together in a bow by a sort of lingering fruitiness difficult to nail down precisely. If the rum had any weakness it might be that the dry finish is relatively lackluster when compared against the complexity of what had preceded it: mostly vanilla, oak, brine, nuts, anise, and little fruit to balance it off.

Clearly the makers, with three aged blends being themselves blended, had to chose between various competing priorities, and balance a lot of different aspects: the various woods and their influence; the presence and absence of salt or sweet or sour or acidity; more strength versus less; the effect of the tannins working with subtler aromatics and esters. That such a tasty rum emerged from all of that is something of a minor miracle, though for my money I felt that the slightly lesser strength made it less indistinct than the stronger and more precisely dialled in coordinates of the 2006 and Principia (which were my comparators along with the Criterion, the 2004 and the Zinfadel).

Clearly the makers, with three aged blends being themselves blended, had to chose between various competing priorities, and balance a lot of different aspects: the various woods and their influence; the presence and absence of salt or sweet or sour or acidity; more strength versus less; the effect of the tannins working with subtler aromatics and esters. That such a tasty rum emerged from all of that is something of a minor miracle, though for my money I felt that the slightly lesser strength made it less indistinct than the stronger and more precisely dialled in coordinates of the 2006 and Principia (which were my comparators along with the Criterion, the 2004 and the Zinfadel).

Perhaps it was too much to hope that the lightning could be trapped in a bottle in quite the same way a second time. The UK bloggers who are so into Foursquare bottlings all claim the thing is as great as the 2006, “just different” but I only agree with the second part of that assessment – it’s different yes, and really good, but nope, not as great. And the subsequent sales values are telling: as of 2021 the 2006 usually auctions for four figures (outdone only by the Velier 70th Destino which is regularly and reliably approaching two thousand pounds) while the Triptych still goes for around two to three hundred.

All that said, I must admit that in the main, I can’t help but admire the Triptych. It’s no small feat to have blended it. To take several ex-bourbon blends and put those together, or to marry a few aged and unaged components, is one thing. To find a way to merge three distinctly separate and differently-aged pot-column blends, to age that and come out the other end with this rum, is quite another. So much could have gone wrong, and so much didn’t — it’s a testament to the hard work and talent of Richard Seale and his team at Foursquare.

(#856)(87/100)

Other Notes

- Outturn is 5400 bottles. Based on the youngest aged portion of the blend you could say it’s a 9 YO rum, though the label makes no such statement

- Given that it came out several years back, clearly others have by now reviewed the rum: Rum Diaries Blog gave it its full throated endorsement and is, as noted, the most deeply informative article available; The Fat Rum Pirate’s 4½-star review is very good; Single Cask Rum was more dismissive with a 78/100 score, and good background notes – I particularly liked his point about the pre-sales hype coming from the perception that it was a Foursquare/Velier product (based on the label) when in fact this was not the case (it was entirely Foursquare’s work). The Rum Shop Boy loved it to the tune of 97 points, while Rum Revelations awarded 94 in a comparative tasting and Serge gave what for him is a seriously good rating of 90.

- I do indeed have a bottle of the Triptych, but the review was done from a sample provided by Marco Freyr. Big hat tip, mein freund….

Historical Note

I’ve remarked on this before, most recently in the opinion piece on flipping, but a recap is in order: when the 2006 ten year old was released in 2016, it flew off the shelves so fast that it became a sort of rueful joke that all online establishments sold out five minutes before the damn things went on sale.

This situation angered a lot of people, because not only did it seem as if speculators or hoarders were buying however much they wanted (and indeed, being allowed to, thereby reducing what was available for people who genuinely wanted to drink the things and share the experience) but almost immediately bottles turned up on the FB trading clubs at highly inflated prices — this was before they were mostly closed down and the action shifted to the emergent auction sites like Rum Auctioneer.

This was seen as a piss-poor allocation and sales issue and some very annoyed posts were aimed at Velier and Foursquare. By the time the Triptych came out, not only were twice as many bottles released, but Richard and Luca came up with a better method of allocation that was the forerunner of the current systems now in play for many of their limited releases. And that’s on top of Richard’s own personal muling services around the festival circuit, to make sure the uber-fans got at least a sample, if not a whole bottle (which always impressed me mightily, since I don’t know any other producer who would do such a thing).

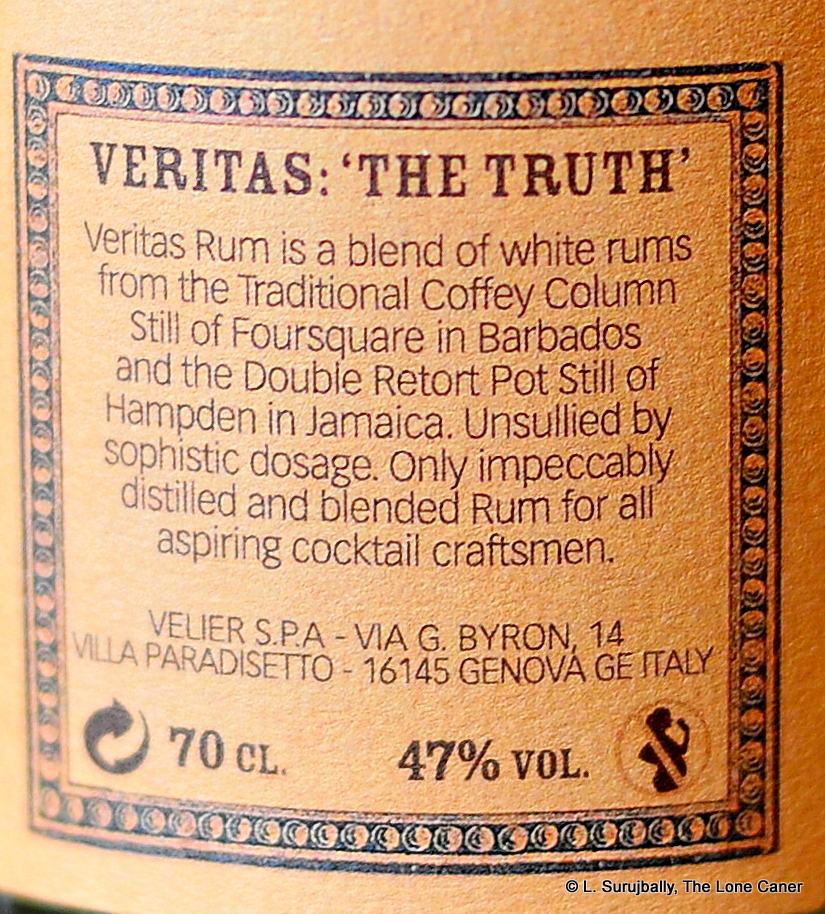

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

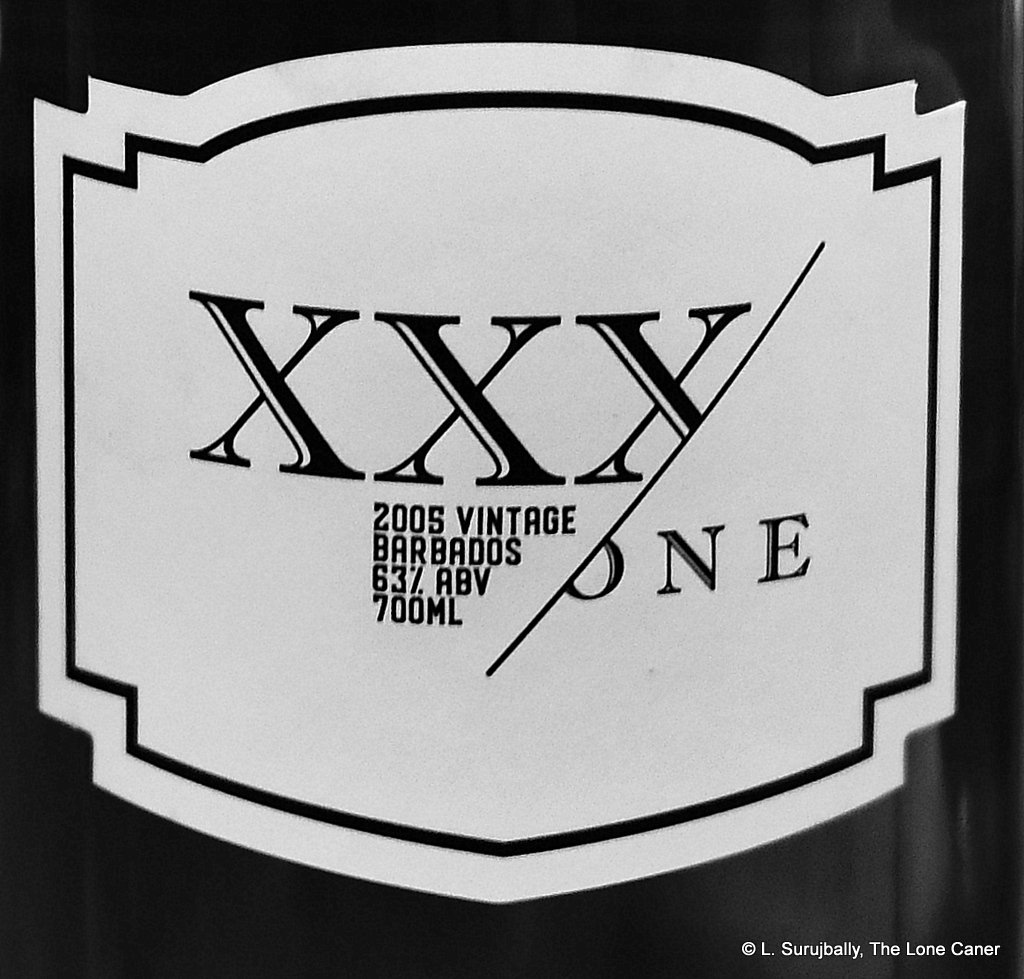

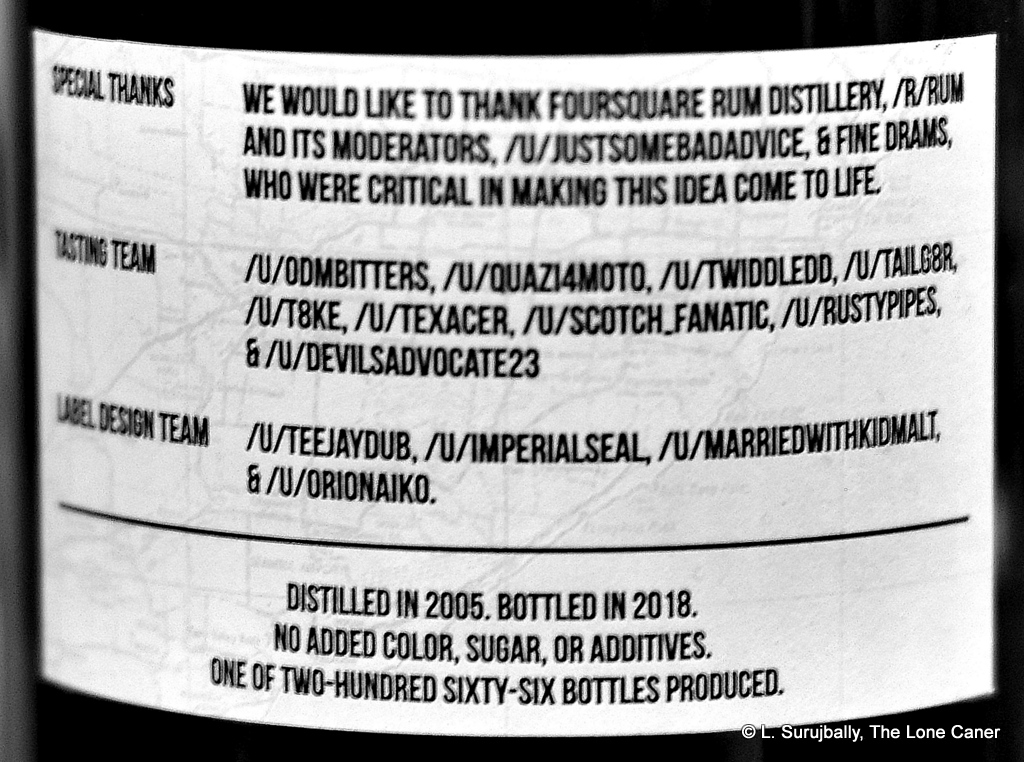

So let’s try it and see what the fuss is all about. Nose first. Well, it’s powerul sharp, let me tell you (63.8% ABV!), both crisper and more precise than the

So let’s try it and see what the fuss is all about. Nose first. Well, it’s powerul sharp, let me tell you (63.8% ABV!), both crisper and more precise than the

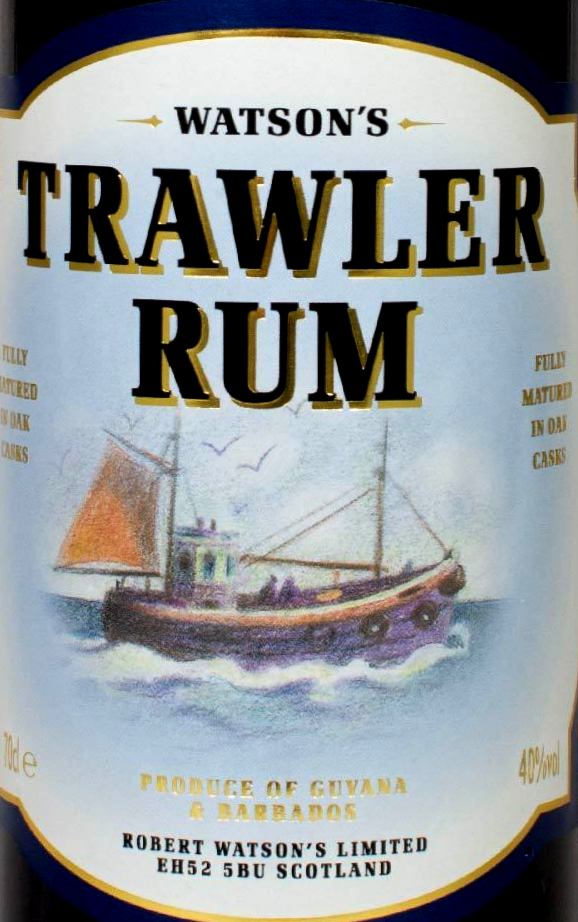

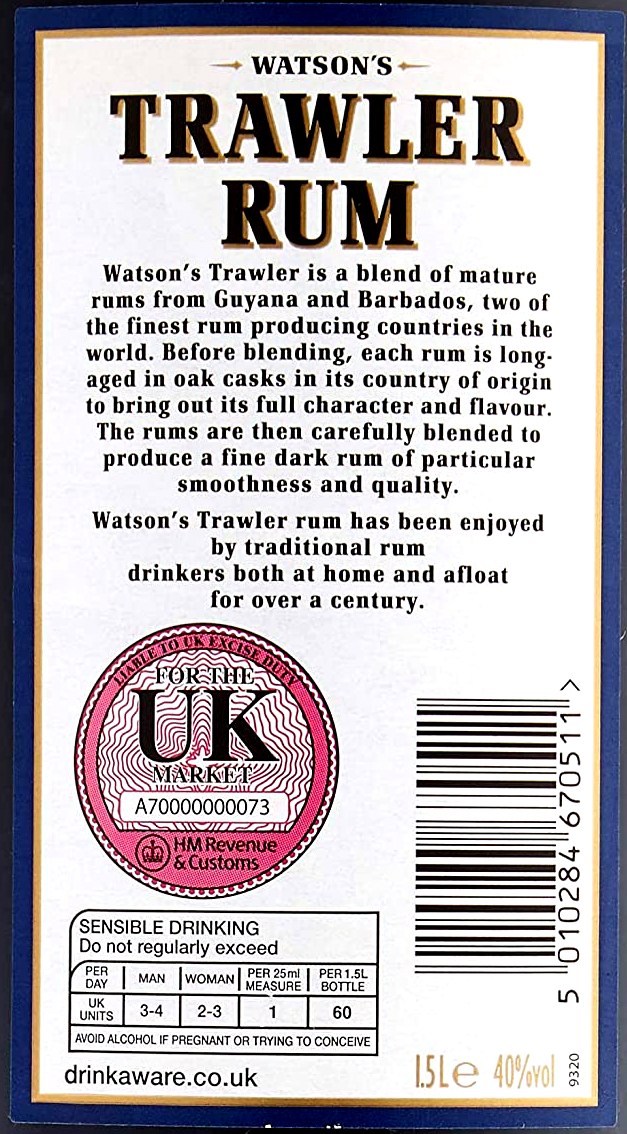

Watson’s Trawler rum, bottled at 40% is another sprig off that branch of British Caribbean blends, budding off the enormous tree of rums the empire produced. The company, according to Anne Watson (granddaughter of the founder), was formed in the late 1940s in Aberdeen, sold at some point to the Chivas Group, and since 1996 the brand is owned by Ian McLeod distillers (home of Sheep Dip and Glengoyne whiskies). It remains a simple, easy to drink and affordable nip, a casual drink, and should be approached in precisely that spirit, not as something with pretensions of grandeur.

Watson’s Trawler rum, bottled at 40% is another sprig off that branch of British Caribbean blends, budding off the enormous tree of rums the empire produced. The company, according to Anne Watson (granddaughter of the founder), was formed in the late 1940s in Aberdeen, sold at some point to the Chivas Group, and since 1996 the brand is owned by Ian McLeod distillers (home of Sheep Dip and Glengoyne whiskies). It remains a simple, easy to drink and affordable nip, a casual drink, and should be approached in precisely that spirit, not as something with pretensions of grandeur. It’s in that simplicity, I argue, lies much of Watson’s strength and enduring appeal — “an honest and loyal rum” opined

It’s in that simplicity, I argue, lies much of Watson’s strength and enduring appeal — “an honest and loyal rum” opined

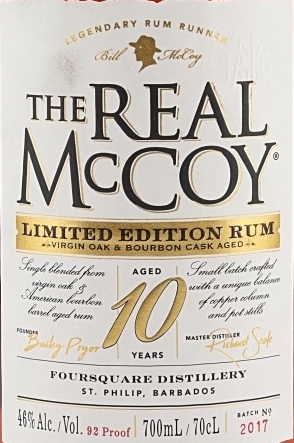

On the palate, the slightly higher strength worked, up to a point. It’s a lot better than 40%, and allowed a certain heft and firmness to brush across the tongue. This then enhanced a melded mishmash of fruits – watermelon, bananas, papaya – plus cocoa butter, coconut shavings in a Bounty chocolate bar, honey and a pinch of salt and vanilla, all of which got shouldered aside by the tannic woodiness. I suspect the virgin oak is responsible for that surfeit, and it made the rum sharper and crisper than those McCoy and Foursquare rums we’re used to, not entirely to the rum’s advantage. The finish summed of most of this – it was dry, rather rough, sharp, and pretty much gave caramel, vanilla, light fruits, and some last tannins which were by now starting to fade. (Subsequent sips and a re-checks over the next few days don’t appreciably change these notes).

On the palate, the slightly higher strength worked, up to a point. It’s a lot better than 40%, and allowed a certain heft and firmness to brush across the tongue. This then enhanced a melded mishmash of fruits – watermelon, bananas, papaya – plus cocoa butter, coconut shavings in a Bounty chocolate bar, honey and a pinch of salt and vanilla, all of which got shouldered aside by the tannic woodiness. I suspect the virgin oak is responsible for that surfeit, and it made the rum sharper and crisper than those McCoy and Foursquare rums we’re used to, not entirely to the rum’s advantage. The finish summed of most of this – it was dry, rather rough, sharp, and pretty much gave caramel, vanilla, light fruits, and some last tannins which were by now starting to fade. (Subsequent sips and a re-checks over the next few days don’t appreciably change these notes).

1423, the Danish indie, has taken this concept a step further with their 2019 release of a Brazil / Barbados carnival — it comprised of 8- and 3-year old Foursquare rums (exact proportions unknown, both column still) to which was added an unaged cachaca from Pirassununga (they make the very popular “51” just outside Sao Paolo), and the whole thing left to age for two years in Moscatel wine casks for two years, before being squeezed out into 323 bottles at 52% ABV.

1423, the Danish indie, has taken this concept a step further with their 2019 release of a Brazil / Barbados carnival — it comprised of 8- and 3-year old Foursquare rums (exact proportions unknown, both column still) to which was added an unaged cachaca from Pirassununga (they make the very popular “51” just outside Sao Paolo), and the whole thing left to age for two years in Moscatel wine casks for two years, before being squeezed out into 323 bottles at 52% ABV.

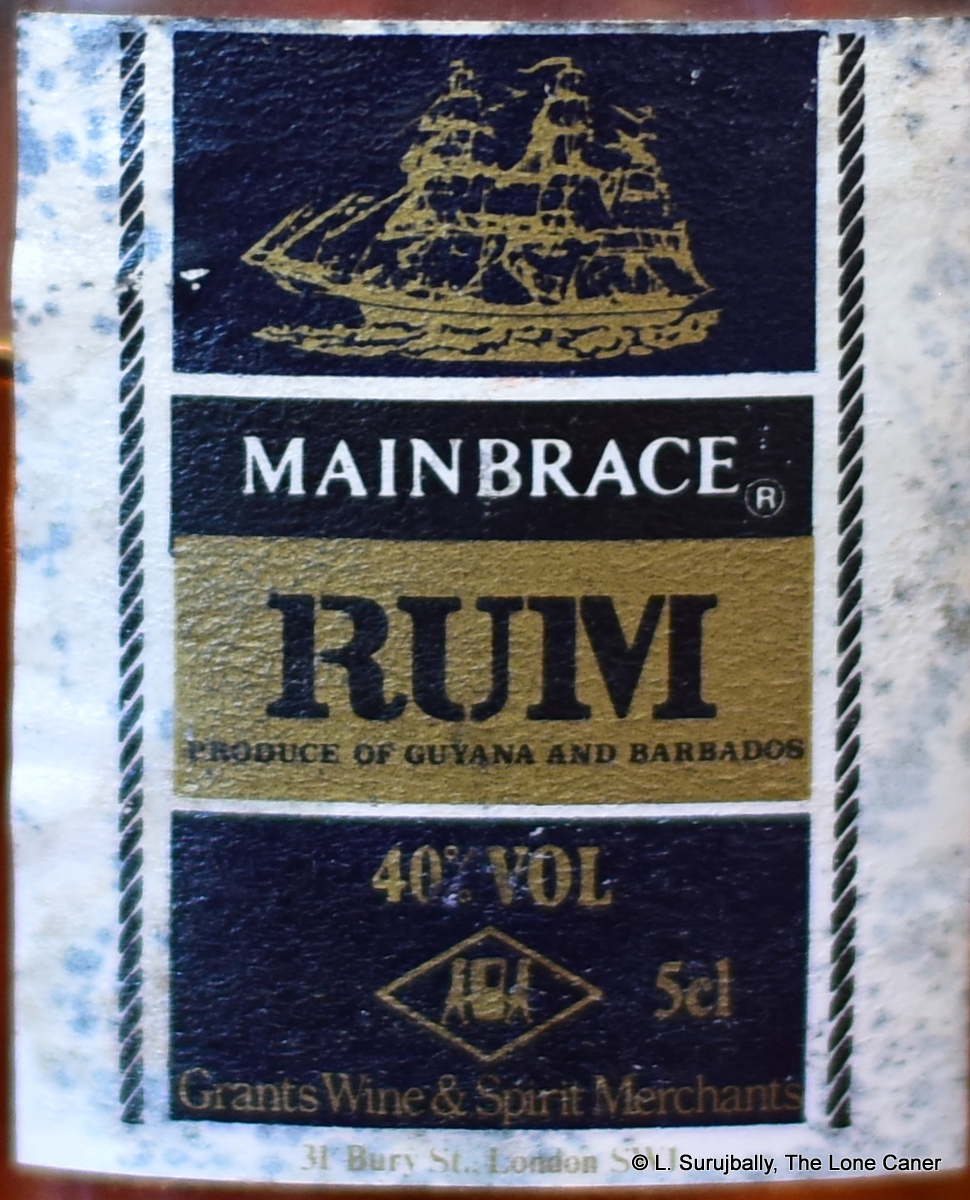

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.  This is a rum that has become a grail for many: it just does not seem to be easily available, the price keeps going up (it’s listed around €300 in some online shops and I’ve seen it auctioned for twice that amount), and of course (drum roll, please) it’s released by Richard Seale. Put this all together and you can see why it is pursued with such slack-jawed drooling relentlessness by all those who worship at the shrine of Foursquare and know all the releases by their date of birth and first names.

This is a rum that has become a grail for many: it just does not seem to be easily available, the price keeps going up (it’s listed around €300 in some online shops and I’ve seen it auctioned for twice that amount), and of course (drum roll, please) it’s released by Richard Seale. Put this all together and you can see why it is pursued with such slack-jawed drooling relentlessness by all those who worship at the shrine of Foursquare and know all the releases by their date of birth and first names.

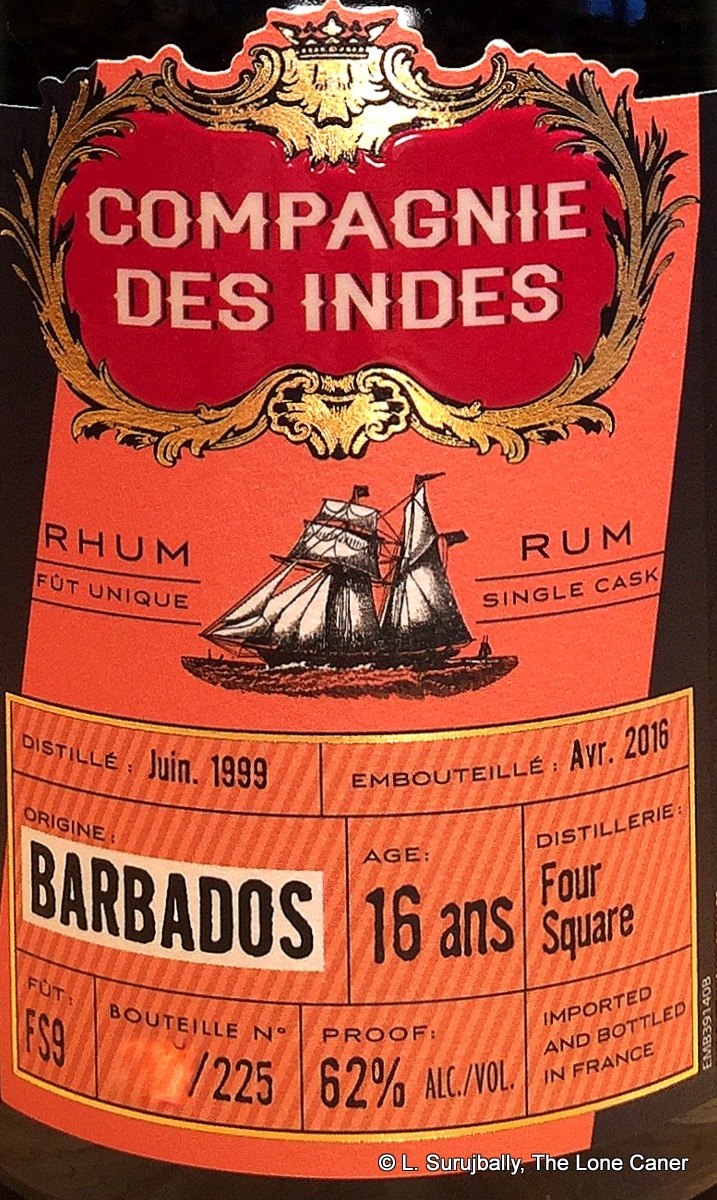

I don’t have any other observations to make, so let’s jump right in without further ado. Nose first – in a word, luscious. Although there are some salty hints to begin with, the overwhelming initial smells are of ripe black grapes, prunes, honey, and plums, with some flambeed bananas and brown sugar coming up right behind. The heat and bite of a 62% strength is very well controlled, and it presents as firm and strong without any bitchiness. After leaving it to open a few minutes, there are some fainter aromas of red/black olives, not too salty, as well as the bitter astringency of very strong black tea, and oak, mellowed by the softness of a musky caramel and vanilla, plus a sprinkling of herbs and maybe cinnamon. So quite a bit going on in there, and well worth taking one’s time with and not rushing to taste.

I don’t have any other observations to make, so let’s jump right in without further ado. Nose first – in a word, luscious. Although there are some salty hints to begin with, the overwhelming initial smells are of ripe black grapes, prunes, honey, and plums, with some flambeed bananas and brown sugar coming up right behind. The heat and bite of a 62% strength is very well controlled, and it presents as firm and strong without any bitchiness. After leaving it to open a few minutes, there are some fainter aromas of red/black olives, not too salty, as well as the bitter astringency of very strong black tea, and oak, mellowed by the softness of a musky caramel and vanilla, plus a sprinkling of herbs and maybe cinnamon. So quite a bit going on in there, and well worth taking one’s time with and not rushing to taste.

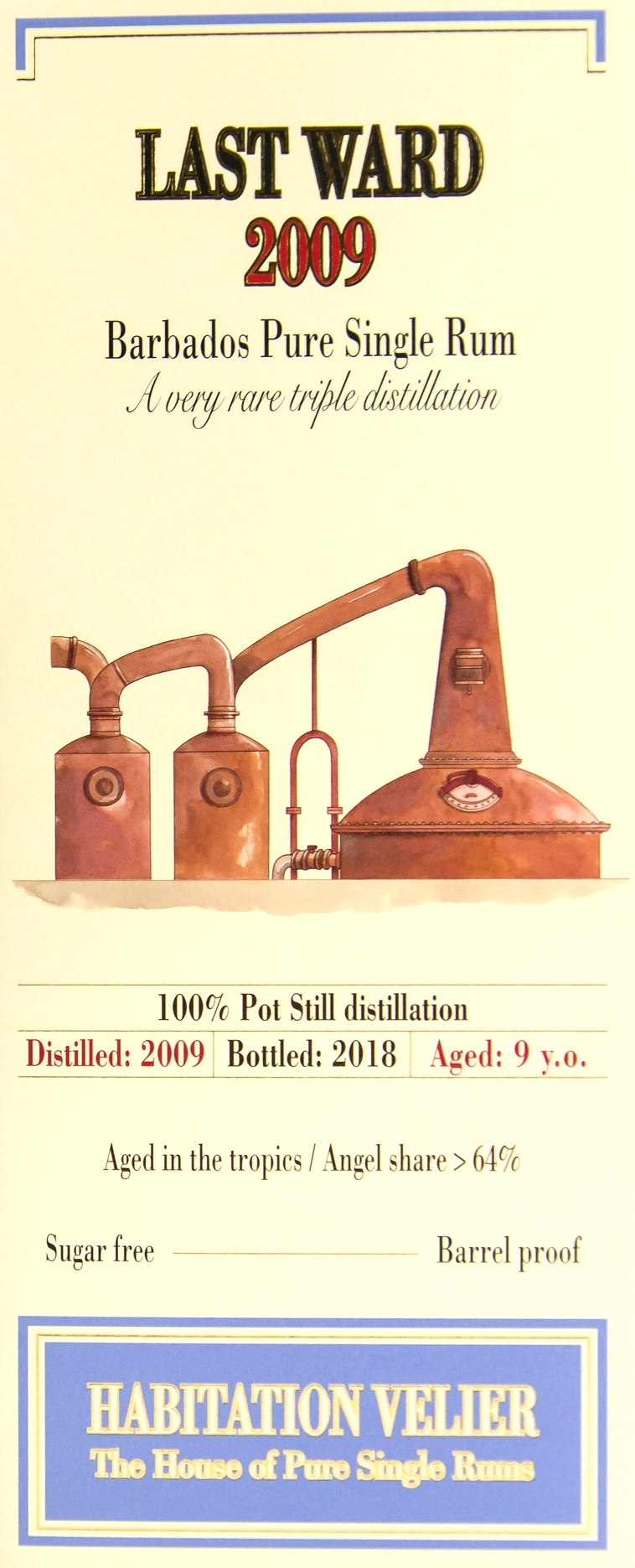

Oh yes…though it is different – some might even sniff and say “Well, it isn’t Foursquare,” and walk away, leaving more for me to acquire, but never mind. The thing is, it carved out its own olfactory niche, distinct from both its older brother and better known juice from St. Phillip. It was warm, almost but not quite spicy, and opened with aromas of biscuits, crackers, hot buns fresh from the oven, sawdust, caramel and vanilla, before exploding into a cornucopia of cherries, ripe peaches and delicate flowers, and even some sweet bubble gum. In no way was it either too spicy or too gentle, but navigated its way nicely between both.

Oh yes…though it is different – some might even sniff and say “Well, it isn’t Foursquare,” and walk away, leaving more for me to acquire, but never mind. The thing is, it carved out its own olfactory niche, distinct from both its older brother and better known juice from St. Phillip. It was warm, almost but not quite spicy, and opened with aromas of biscuits, crackers, hot buns fresh from the oven, sawdust, caramel and vanilla, before exploding into a cornucopia of cherries, ripe peaches and delicate flowers, and even some sweet bubble gum. In no way was it either too spicy or too gentle, but navigated its way nicely between both.

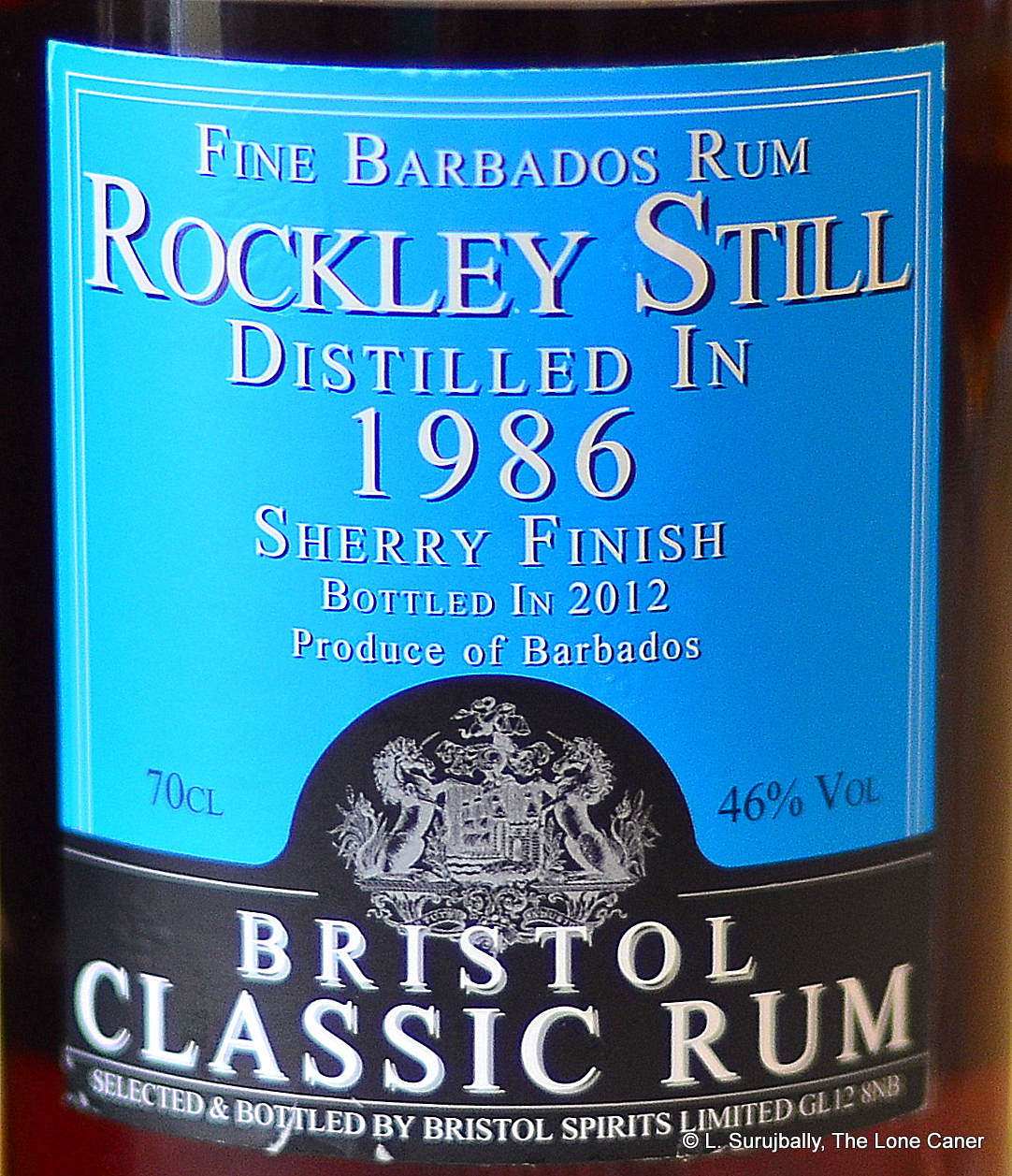

The brief technical blah is as follows: bottled by Bristol Spirits out of the UK from distillate left to age in Scotland for 26 years; a pot still product (I refer you to

The brief technical blah is as follows: bottled by Bristol Spirits out of the UK from distillate left to age in Scotland for 26 years; a pot still product (I refer you to

Tasting revealed somewhat less clothing in the suitcase, though it was quite a decent rum to sip (mixing it is totally unnecessary) – it was a little sharp before settling down into a relative smooth experience, and tasted primarily of white and watery fruits (pears, watermelon, white gavas), cereals, coconut shavings, sweet wine, and had a sly hint of tart red fruiness that was almost, but not quite sour, behind it all – red currants, cranberries, grapes. It was quite light and easy and escaped being an alcohol-flavoured water in fine style – not bad for something at close to standard strength, and the touch of sweet fruitiness imparted by the Zin barrels was in no way overdone. Even the finish was quite pleasant, being warm, relatively soft, and closing off the show with some tart fruitiness, coconut shavings, vanilla, milk chocolate, salted caramel, french bread (!!) and touch of thyme.

Tasting revealed somewhat less clothing in the suitcase, though it was quite a decent rum to sip (mixing it is totally unnecessary) – it was a little sharp before settling down into a relative smooth experience, and tasted primarily of white and watery fruits (pears, watermelon, white gavas), cereals, coconut shavings, sweet wine, and had a sly hint of tart red fruiness that was almost, but not quite sour, behind it all – red currants, cranberries, grapes. It was quite light and easy and escaped being an alcohol-flavoured water in fine style – not bad for something at close to standard strength, and the touch of sweet fruitiness imparted by the Zin barrels was in no way overdone. Even the finish was quite pleasant, being warm, relatively soft, and closing off the show with some tart fruitiness, coconut shavings, vanilla, milk chocolate, salted caramel, french bread (!!) and touch of thyme.