William Hinton from Madeira is not a name to conjure with in the annals of rum, but this is not the first time they have come up for mention – their distillery produced the Engenho Novo da Madeira rum that Rum Nation released with some fanfare back in 2017. The following year the company of Engenho Novo, Hinton’s new incarnation (and not to be confused with Engenhos do Norte, producer of the “970 Agricola”) released some rums for themselves, and we’ll be looking at these over the next week or so.

William Hinton from Madeira is not a name to conjure with in the annals of rum, but this is not the first time they have come up for mention – their distillery produced the Engenho Novo da Madeira rum that Rum Nation released with some fanfare back in 2017. The following year the company of Engenho Novo, Hinton’s new incarnation (and not to be confused with Engenhos do Norte, producer of the “970 Agricola”) released some rums for themselves, and we’ll be looking at these over the next week or so.

Hinton classify their rums into three tiers: (1) the exclusive single casks, which are blends of 6YO “new Hinton” rums and 25 YO “old Hinton” rums from before the shutdown in 1986 (see below) which are then finished in various other barrels like wine or whisky or what have you; (2) the premium range which consists of two rums, an award winning 6 YO and a high proof white; and (3) the bartenders’ mixes, for general audiences, which their website refers to, in an odd turn of phrase, as a “service rum.” One of that final category is the white rum we’re examining today.

The white is a cane juice agricole – a term which Madeira has a right to use – but it is not unaged. While the site does not specifically say so, I was told it’s under a year, around six months, in French oak casks 1. It is bottled at 40%, column still, so nothing “serious”. It’s made fit for purpose, that’s all.

Unfortunately that purpose seems to be to put me to sleep. Dare I say it is underwhelming? It is a soft and extremely light white rum with very little in the way of an aromas at all. It’s delicate, flowery and admittedly very clean – and one has to seriously pay attention to make out some flowers, dill, herbs, grass, sugar water and wet moss (!!), before it disappears like a summer zephyr you barely sensed in the first place

The palate is better, and remains light and clean. It has a queer sort of dusty aroma to it, like old library books stored in long disused storage room. That gradually goes away and is replaced with a dry taste of cheerios, and some fruits. Almonds and a curiously faint whiff of vanilla. I read somewhere that this white is made to service a poncha — a very old cocktail from Portugal’s great seafaring days invented to combat scurvy (rum plus sugar plus lemon juice, and some honey) — not so much to replace Bacardi Superior … though you could not imagine them being displeased if it did. Drinking it neat is probably a nonstarter since it’s so wispy, and of course there’s not much of a finish (at 40% I wasn’t looking for one). Briefly fruity and floral, a quick whiff of herbs, and it’s gone.

Although it has some very brief tastes and aromas that I suppose derive from the minimal ageing (before the results of that process got filtered right back out again), the white displays little that would make it stand out. In fact, while demonstrably being an agricole, it hardly tastes like one at all. It’s what I’m beginning to refer to more and more often as a “cruise-ship white”, a kind of all-encompassing milquetoast rum whose every character has been bleached and out so its only remaining function is to deliver a shot of bland alcohol (like, say, vodka) into a mixed drink for those who don’t know or don’t care (or both).

Although it has some very brief tastes and aromas that I suppose derive from the minimal ageing (before the results of that process got filtered right back out again), the white displays little that would make it stand out. In fact, while demonstrably being an agricole, it hardly tastes like one at all. It’s what I’m beginning to refer to more and more often as a “cruise-ship white”, a kind of all-encompassing milquetoast rum whose every character has been bleached and out so its only remaining function is to deliver a shot of bland alcohol (like, say, vodka) into a mixed drink for those who don’t know or don’t care (or both).

That said, honesty compels me to admit that there was some interesting stuff in the wings, sensed but not seen, a trace only, perhaps only waiting to emerge at the proper time, but alas, not enough to save it. The premium series probably address such deficiencies, and if so, it was a smart move to separate the generalized cocktail fodder (which this is) from a more upscale and dangerous version aimed at more masochistic folks who’ll try anything once. If you want to know the real potential of Hinton’s white rum, don’t stop and waste time dawdling with this one, go straight for the 69% and be prepared to have your socks blown off. Unless you like soft and easy whites, I’d walk away from this one.

(#829)(75/100)

Background & History

It’s long been noted that sugar cane migrated from Indonesia to India to the Mediterranean, and continued its westward march by being cultivated on Madeira by the first half of the 15th century. From there it jumped to the New World, but sugar remained a stable and very profitable cash crop in Madeira and the primary engine of the island’s economy for two hundred years. At that point, with Brazil and other Portuguese colonies becoming the main sources of sugar, the focus of Madeira switched to wine, for which it became renowned (sugar cane production continued, just at a reduced level).

The British took some involvement in the island in the 1800s, which led to several inflows of their citizens, some of whom stayed – one of these was William Hinton, a businessman who arrived in 1838 and started the eponymous company seven years later. First a sugar factory was constructed and a distillery was added — these were large and technologically advanced and allowed Engenho Hinton to become the largest sugar processor on the island, as well as the largest rum maker (though I’m not sure what rums they actually did produce) by the 1920s.

Unfortunately, by the 1970s and 1980s as sugar production became more and more industrialized and global, more cheaply produced sugar from Brazil and India and elsewhere cut into Hinton’s sales (they were part of a regulated EEC industry, so low-cost labour was not an option), and by 1986 the factory and distillery closed and the facilities were mothballed – the website gives no reasons for the closure, so I’m making an educated guess here, as well as assuming they did not sell off or otherwise dispose of what bean counters like me like to refer to as “plant”.

It was restarted by Hinton’s heirs in 2006 as Engenho Novo de Madeira with a column still and using Madeira sugar cane: here again there is scanty information on where this sugar cane comes from, their own property or bought from others. Whatever the source, the practice of using rendered sugar cane juice (”honey”) continued and notes from a brochure I have state that the column still was one restored in 1969 and again in 2007, suggesting that when the distillery closed, its equipment remained intact and in place.

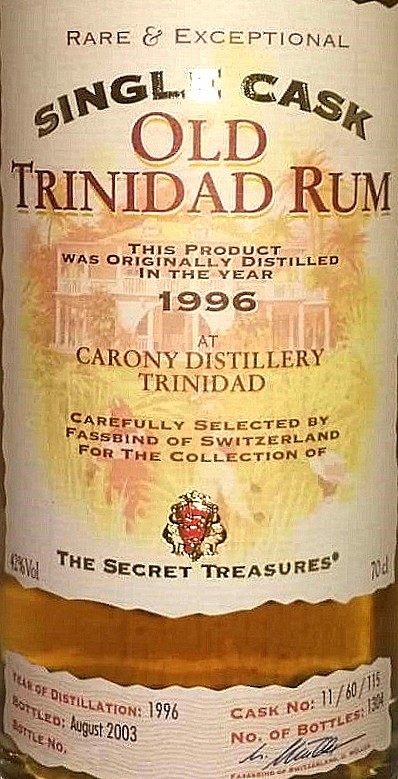

There are some older bottles in the review queue for products from what I term the “classic” era of the Swiss / German outfit of Secret Treasures, and it’s perhaps time to push them out the door in case some curious person ever wants to research them for an auction listing or something. Because what Secret Treasures are making now is completely different from what they did then, as I remarked in my brief company notes for

There are some older bottles in the review queue for products from what I term the “classic” era of the Swiss / German outfit of Secret Treasures, and it’s perhaps time to push them out the door in case some curious person ever wants to research them for an auction listing or something. Because what Secret Treasures are making now is completely different from what they did then, as I remarked in my brief company notes for  In the maelstrom of ongoing indie releases coming at us from every direction almost every month, it’s easy to overlook some of the older rums, or even some of the older companies. Secret Treasures is one of these — I had discovered their charms on the same trip where I found the first Veliers, all those long years ago, at a time when the concept of independent bottlers was a relatively small scale phenomenon. Back then I bought the company’s

In the maelstrom of ongoing indie releases coming at us from every direction almost every month, it’s easy to overlook some of the older rums, or even some of the older companies. Secret Treasures is one of these — I had discovered their charms on the same trip where I found the first Veliers, all those long years ago, at a time when the concept of independent bottlers was a relatively small scale phenomenon. Back then I bought the company’s  A salty sweet sugar water greets the tongue with warmth and firmness. All the fleshy and watery fruits we’re familiar with parade around – pears, watermelons, white guavas, papaya, kiwi fruits, even cucumbers all take a bow. A trace of olives and occasional whiff of strawberries and petrol are barely noticeable, so one can only wonder where, after such a promising beginning, they all vanished to. Eloped, maybe. Certainly they bailed and left the rum with nothing but memories and a good wish to lead to its inevitably disappointing denouement, which was short, breathy, light and watery, and barely registered some vanilla, brine, a fruit or two and exactly zero points of distinction.

A salty sweet sugar water greets the tongue with warmth and firmness. All the fleshy and watery fruits we’re familiar with parade around – pears, watermelons, white guavas, papaya, kiwi fruits, even cucumbers all take a bow. A trace of olives and occasional whiff of strawberries and petrol are barely noticeable, so one can only wonder where, after such a promising beginning, they all vanished to. Eloped, maybe. Certainly they bailed and left the rum with nothing but memories and a good wish to lead to its inevitably disappointing denouement, which was short, breathy, light and watery, and barely registered some vanilla, brine, a fruit or two and exactly zero points of distinction.

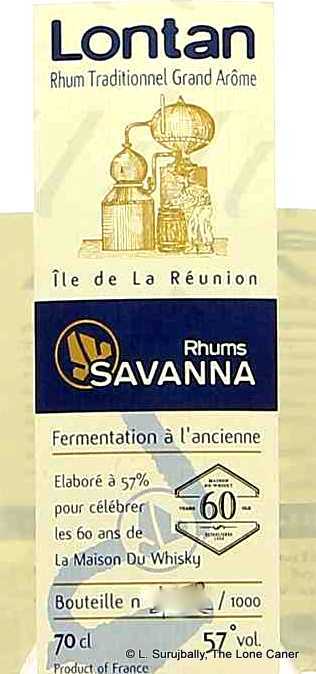

Still, this 57% ABV grand arôme, which was released in 2016 for La Maison Du Whisky’s 60th Anniversary (they went into partnership with Velier the following year and formed LM&V), seemed at pains to make the point yet again. In this case, it clearly wanted to channel a cachaca duking it out with a DOK, for it nosed pretty much like they were having a serious disagreement: vegetables and oversweet fruits decomposing on a hot day in a market someplace tropical; herbs, wet grass, sweet pickles, hot dog relish (I know what this sounds like!); sugar water; iodine, papaya, strawberries; wax, brine and cucumbers in a light pimento-soaked vinegar. I mean, seriously, does that remind you of any rum you’ve ever tried? I both liked it and wondered where the rum was hiding.

Still, this 57% ABV grand arôme, which was released in 2016 for La Maison Du Whisky’s 60th Anniversary (they went into partnership with Velier the following year and formed LM&V), seemed at pains to make the point yet again. In this case, it clearly wanted to channel a cachaca duking it out with a DOK, for it nosed pretty much like they were having a serious disagreement: vegetables and oversweet fruits decomposing on a hot day in a market someplace tropical; herbs, wet grass, sweet pickles, hot dog relish (I know what this sounds like!); sugar water; iodine, papaya, strawberries; wax, brine and cucumbers in a light pimento-soaked vinegar. I mean, seriously, does that remind you of any rum you’ve ever tried? I both liked it and wondered where the rum was hiding. This is not the first Demerara rum that the venerable Italian indie bottler Moon Import has aged in sherry barrels: the superb

This is not the first Demerara rum that the venerable Italian indie bottler Moon Import has aged in sherry barrels: the superb

Opinion

Opinion

Whatever the case, I must advise you that if you like agricoles at all, those smaller names and lesser known establishments like Dillon should be on your radar. Not all of the rhums they make are double-digit aged, so those that are, even if farmed out to a third party, are even more worth looking at. Just smell this one, for example: it’s a fruitarian’s wet dream. In fact, the aroma almost strikes me like a very good Riesling mixing it up with a 7-up, if you could conceive of such an unlikely pairing. Lighter than the

Whatever the case, I must advise you that if you like agricoles at all, those smaller names and lesser known establishments like Dillon should be on your radar. Not all of the rhums they make are double-digit aged, so those that are, even if farmed out to a third party, are even more worth looking at. Just smell this one, for example: it’s a fruitarian’s wet dream. In fact, the aroma almost strikes me like a very good Riesling mixing it up with a 7-up, if you could conceive of such an unlikely pairing. Lighter than the

The nose doesn’t help narrow down the origin (though I have my suspicions), and the palate doesn’t either – but it

The nose doesn’t help narrow down the origin (though I have my suspicions), and the palate doesn’t either – but it

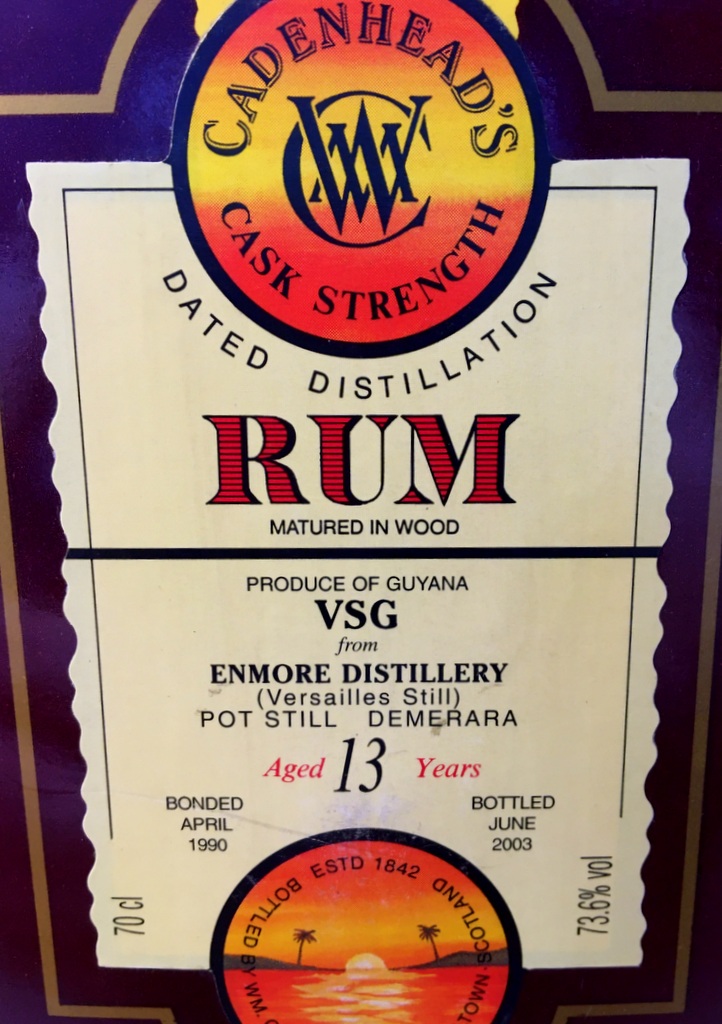

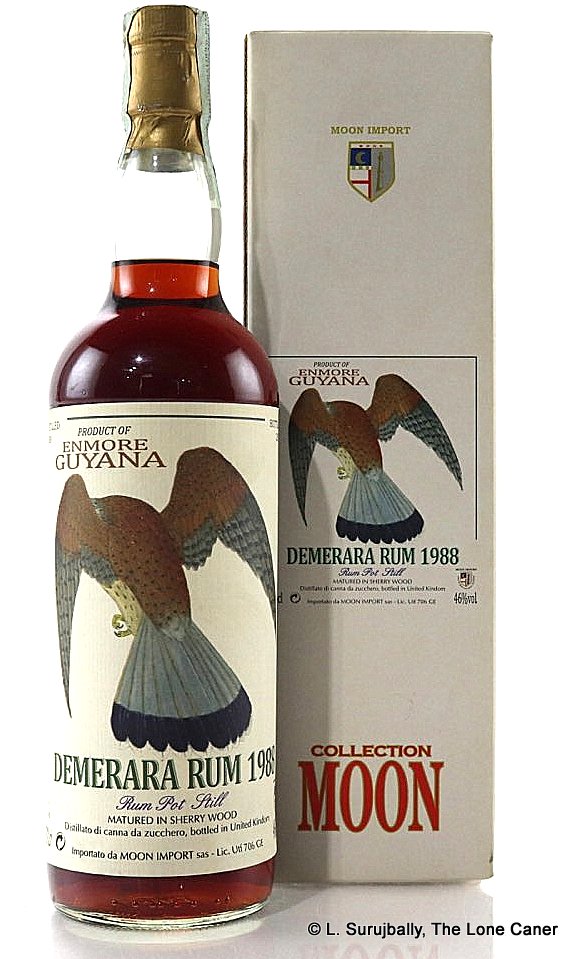

I do, on the other hand, like the taste. It’s warm and rich and the Enmore still profile – freshly sawn lumber, sawdust, pencil shavings – is clear. Also sour cream, eggnog, and bags of dried, dark fruits (raisins, prunes, dried plums) mix it up with a nice touch of sandalwood. It takes its own sweet time getting the the point and is a little discombobulated throughout, but I can’t argue with the stewed apples, dried orange peel, ripe red guavas and licorice – it’s nice. The finish is quite solid, if unexceptional: it lasts a fair bit, and you’re left with closing notes of licorice, oak chips, vanilla, dried fruit and black cake.

I do, on the other hand, like the taste. It’s warm and rich and the Enmore still profile – freshly sawn lumber, sawdust, pencil shavings – is clear. Also sour cream, eggnog, and bags of dried, dark fruits (raisins, prunes, dried plums) mix it up with a nice touch of sandalwood. It takes its own sweet time getting the the point and is a little discombobulated throughout, but I can’t argue with the stewed apples, dried orange peel, ripe red guavas and licorice – it’s nice. The finish is quite solid, if unexceptional: it lasts a fair bit, and you’re left with closing notes of licorice, oak chips, vanilla, dried fruit and black cake.

Depaz’s 45% rhum blanc agricole is not one of these uber-exclusive, limited-edition craft whites that uber-dorks are frothing over. But the quality and taste of even this standard white shows exactly how good the

Depaz’s 45% rhum blanc agricole is not one of these uber-exclusive, limited-edition craft whites that uber-dorks are frothing over. But the quality and taste of even this standard white shows exactly how good the

Tasting notes. The nose is nice. At under 50% not too much sharpness, just a good solid heat, redolent of soda, fanta, coca cola and strawberries. There’s a trace of coffee and rye bread, and also a nice fruity background of apples, green grapes, yellow mangoes and kiwi fruit. It develops well and no fault can found with the balance among these disparate elements.

Tasting notes. The nose is nice. At under 50% not too much sharpness, just a good solid heat, redolent of soda, fanta, coca cola and strawberries. There’s a trace of coffee and rye bread, and also a nice fruity background of apples, green grapes, yellow mangoes and kiwi fruit. It develops well and no fault can found with the balance among these disparate elements.