In my rum drinking life, I have been extraordinarily fortunate to have tasted up and down the pantheon of great and not so great Guyanese rums – blends, single still bottlings, caskers, aged dinosaurs, special editions, the works. These days independent bottlers and single barrel offerings hog the lion’s share of the limelight, the rums of Velier remain grail quests for many, and therefore DDL’s standard offerings (3, 5, 8, 12, 15 and 21 year olds) which put Guyana and the famed wooden stills on the map have lost a little of their lustre. Yet, perhaps because of their relative rarity – and price – the 25 year old editions which DDL releases every few years still have something of a cachet… which, to this reviewer, is not always deserved.

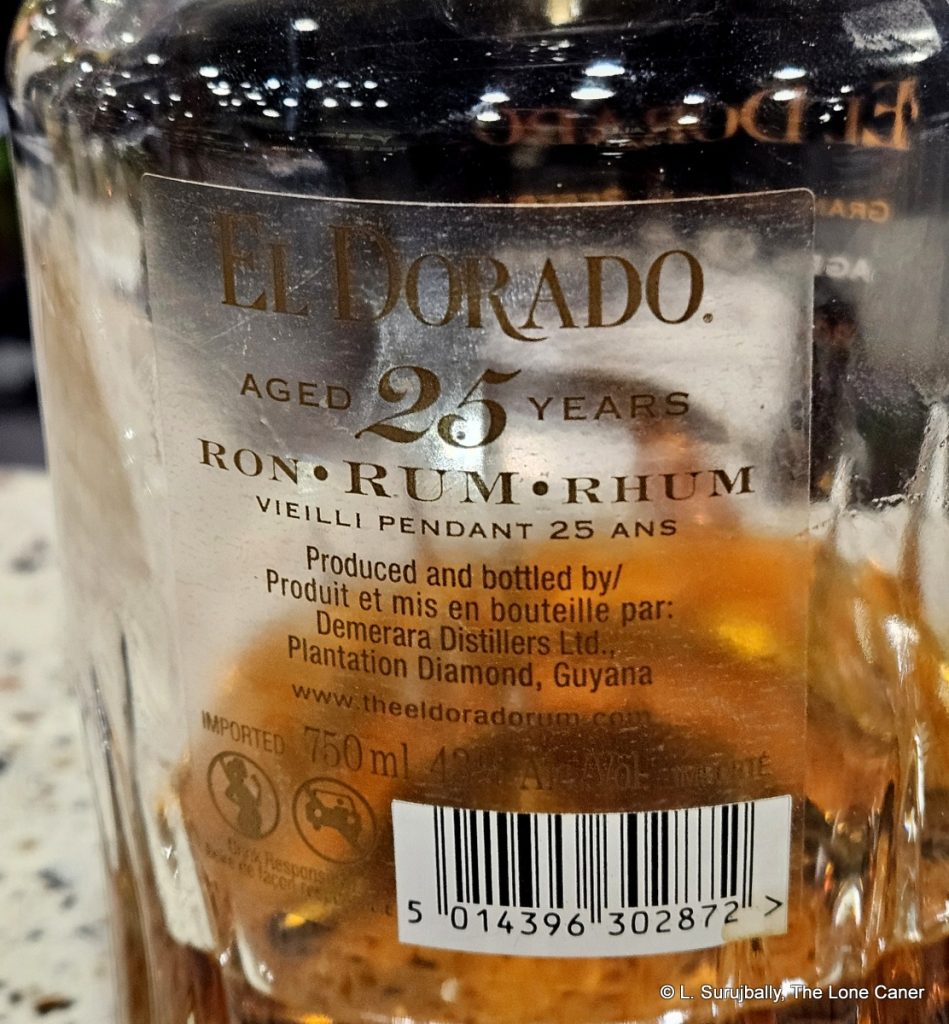

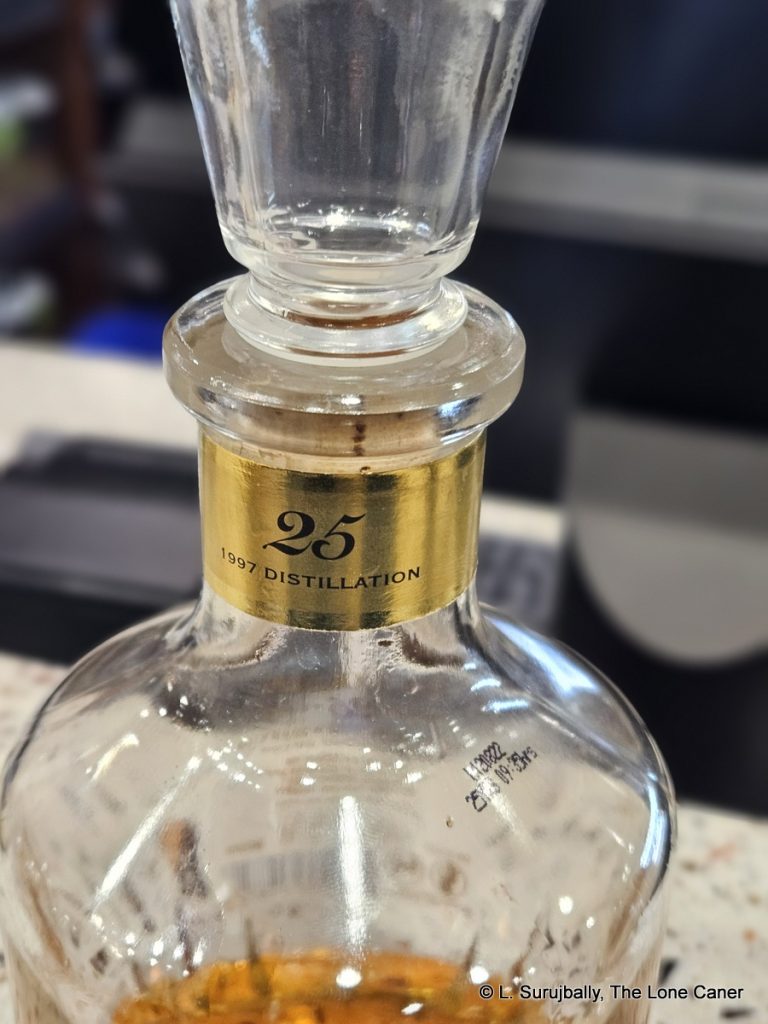

Thus far, and going from memory, there have been six 25YO rums in the series, distilled in 1975 (the Millenium Edition), 1980, 1986, 1988, 1992 and now, this one, in 1997. If there are others, I don’t know about them. All have been at either 40% or 43% ABV, all are housed in handsome gold-leaf-embossed decanters with a glass and cork stopper, and all are reasonably tasty. And as an aside, in no case are we ever told anything about the components of the blend, though it is a reasonable assumption that there are heritage still components, maybe some French Savalle still juice, and marques from all over the map. DDL knows, of course, but they aren’t telling us, and reviewers who have tried them and written about them thus far (and there aren’t many), are equally scant on the details. We’ll have to live with that, I suppose.

I’ve sampled all but one of them thus far, and some time back, had a lot of fun writing a biblical screed against the 1986 and its dosage. The rums are easy drinking, complex to a fault, just lacking the background that would enable us to evaluate them better. Paradoxically however, this makes us pay rather more attention to them, since we walk in with no preconceived notions, no knowledge, no expectations – and so we have to do all the work ourselves.

I’ve sampled all but one of them thus far, and some time back, had a lot of fun writing a biblical screed against the 1986 and its dosage. The rums are easy drinking, complex to a fault, just lacking the background that would enable us to evaluate them better. Paradoxically however, this makes us pay rather more attention to them, since we walk in with no preconceived notions, no knowledge, no expectations – and so we have to do all the work ourselves.

It’s not a bad rum, all in all – the 43% strength makes it a very approachable, soft nosing experience, and it’s gentle to a fault, though some might sniff disparagingly that it’s actually somewhat thin. It starts with a deceptively straightforward series of aromas: caramel, toffee, white chocolate, almonds and vanilla, with traces of molasses, oak tannins and leather. Some spices slowly meander into the frame – cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg – accompanied after a few minutes, by raisins, peaches, apricots and green apples. But I must mention this: the rum really opens up slowly, and none of this is evident right off the bat. It’s a rum that rewards more patience than usual, and I’d suggest letting it stand for at least five minutes before really getting into it.

The same comments are applicable to what it tastes like. It’s maintains some edge, mostly tannics and slight bitterness (it’s very likely that the dosage is minimal here, but this is an opinion, since I was unable to test it). The standard notes that characterize so many El Dorado rums are all there: molasses, bitter chocolate, light wood shavings, licorice, caramel, toffee. It’s the fruits that are key here – they come late to the party, but once they do, the thing gets better in a hurry as they coil over the palate and make themselves felt: so, we taste raisins, peaches, apricots, very ripe yellow mangoes on the cusp of going off, plus a well balanced series of spices like cinnamon, vanilla and a dusting of nutmeg, leading to a soft and gentle finish that, alas, is gone all too quickly, and sums up most of the preceding elements without adding anything new.

The same comments are applicable to what it tastes like. It’s maintains some edge, mostly tannics and slight bitterness (it’s very likely that the dosage is minimal here, but this is an opinion, since I was unable to test it). The standard notes that characterize so many El Dorado rums are all there: molasses, bitter chocolate, light wood shavings, licorice, caramel, toffee. It’s the fruits that are key here – they come late to the party, but once they do, the thing gets better in a hurry as they coil over the palate and make themselves felt: so, we taste raisins, peaches, apricots, very ripe yellow mangoes on the cusp of going off, plus a well balanced series of spices like cinnamon, vanilla and a dusting of nutmeg, leading to a soft and gentle finish that, alas, is gone all too quickly, and sums up most of the preceding elements without adding anything new.

So, let’s clear the dishes: we have a pot-column-still blend of unknown marques, aged a minimum of 25 years – nobody has ever put a dent in DDL’s age statements – and issued at 43%. On the surface, it ticks all the right boxes: easy drinking for those with deep pockets but perhaps not as much experience with rums; a luxury cachet from one of the best known rum brands in the world; and enough complexity for those who know what to look for. What it doesn’t have is single-still distinctiveness, which may be a downer for some, though I argue that in a blend this old, perhaps that may be expecting too much.

For those who have been weaned on sterner, stronger stuff, this may be seen as weak gruel and slim pickings, yet I argue if one accepts that and simply enjoys what’s there, there are treasures to be discovered and appreciated. The El Dorado 25 year old series has never been one for amazing off-the-charts tastes – it’s the age that is the selling point, not the uniqueness of the profile. These days, with indie bottlers releasing decades old juice with some regularity, perhaps this doesn’t press all the buttons. Yet here, even within those limitations, the rum presents well, and if it was cheaper, I’d probably go out there and buy it on the spot.

(#1123)(85/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other notes

- Video recap link

- Outturn is unknown

- In Calgary I saw it selling for about Can$400. In Toronto’s LCBO, it goes for $550. That of course does not compare with the recent Appleton Estate 51YO 62% rum supposedly selling for $70,000, but it’s still a pretty hefty price tag for us proles who watch our wallets.

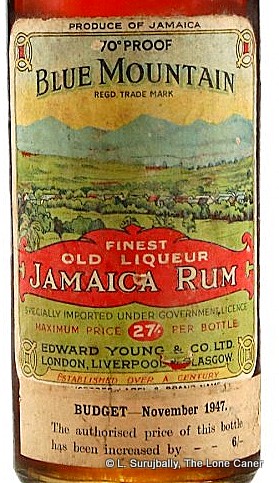

Company Bio

Company Bio