First posted 11 July 2011 on Liquorature and the Rum Connection

This review first appeared in two parts on the Rum Connection website, here. It is reposted here with minor corrections and amendments. It’s a bit of a rant, I’m afraid, and somewhat overlong…it speaks to my disappointment in what has been touted as an ultra-premium, but isn’t.

I enjoy the Pyrat’s XO rum about as much as I do the leisurely explorations of my favourite proctologist: the thing is a perennial dust-gatherer on my shelf, and I finally traded it away to the Arctic Wolf in Edmonton. And when one considers the abysmal regard I have for its enormous tangerine nose, one could reasonably ask what business I had shelling out four times as much to buy the brand’s top-end product, the Cask 1623. Truth is, it was like a splinter lodged in my mind for over a year, and no matter how many times I passed it squatting smugly there behind a glass case, I could never get rid of the impression it was sneering at me and calling me a puling, whining cheapskate. So the other day when I had some disposable income, I finally said to hell with it, and got ‘er.

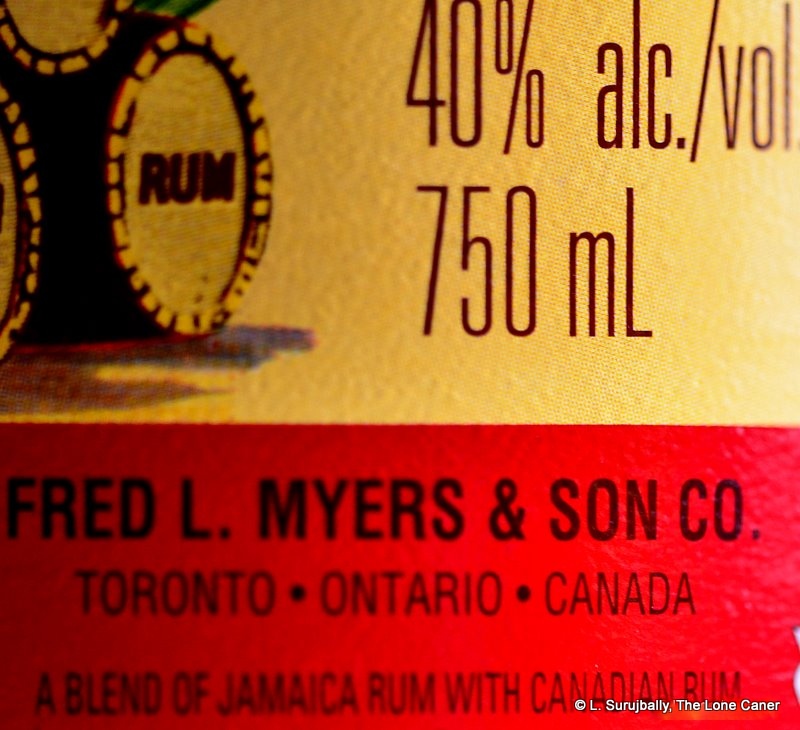

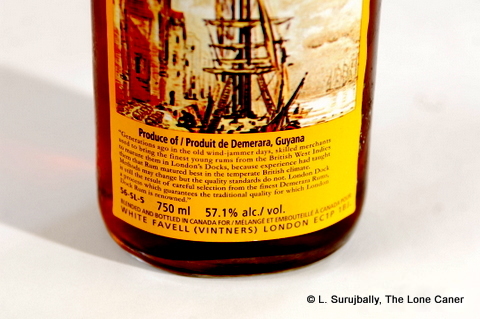

Pyrat’s is a product of the Anguilla Rums company. This is an establishment with its own origin story (whether true or not, it’s still fun reading) regarding a travelling seaman called CJ Planter who fell in love with an island girl who may have been the illegitimate daughter of a plantation owner and a local lady who dabbled in witchcraft. CJ eventually began a rum-making concern which, it must be emphasized, did not create rums from scratch, but blended rums from elsewhere (which continues today – I imagine this is because Anguilla, a beautiful but tiny speck in the Caribbean which if you sneezed at the wrong time you’d miss as you flew over it, lacks the resources to have full blown sugar cane plantations on the available land). Subsequent digging suggests that the Pyrat brand is actually owned by a Nevada outfit called the Patron Spirits Company, and they have a line of spirits products that extends from Patron tequila, to Ultimat vodka, to liqueurs, and rums. So do they own the Anguilla company? Don’t know…probably they are acting as marketing and distribution agents for the factory, which, as Ed Hamilton of the Ministry of Rum notes, was shut down in 2010. Note that the rum is now made from DDL’s rum stock from Guyana, and given the shutdown in Anguilla, it’s very likely that the blending takes place in Guyana as well (I was not able to definitely confirm this beyond the anecdotal, but Arctic told me they definitely bottle it there, so it seems reasonable).

Be that as it may, I must commend them for the mere look of the package. I’m a sucker for a good presentation; it’s part of the overall aesthetic, I argue, much to the disgust of the various maltsters of my acquaintance, who refuse to be sidetracked by such mundane matters and make no bones about chucking wrapper, box and bunting as soon as they buy a bottle of anything. Here, Pyrat’s delivers, and this is as it should be for a self-annointed “ultra-premium” rum costing north of two hundred bucks. The hand blown bottle is encased in a wooden box (the Pyrat homepage says cedar, but I notice one reviewer says walnut, and from the lack of an aroma, walnut is my take also), and around its neck is a medallion with the patron saint of fortune tellers and bartenders, Hoti. And there’s a hand lettered label signed by the master blender. Pretty cool.

The rum is a dark amber colour, and has a heavy look to it. The cork is a real cork, no extras or plastic anything. And as soon as I opened the stopper, I knew I’d been had. Well, perhaps not – perhaps I’d allowed myself to be had in my eagerness to try something new at the supposed top end of the scale. The nose wafted out and it was immediately clear that customers of the XO had written in and started a campaign to assure Pyrat’s that the citrus they had sensed in the XO — the very thing I had disliked so much about it – was for wussies and they demanded something with just as much or more orange heft: and Pyrat’s complied. Open the botle and the waft of an orange grove comes right at you.

There’s a sullen, sulky heaviness to it when it pours into your glass that reminds you of a lighter-coloured El Dorado – and the legs were relatively slow and fat as they slid down the sides, so that part was good. But nosing it was about as subtle as the grapefruit scene with Mae Clark in 1931’s “Public Enemy”. Yes, I got vanilla (and I had to strain for that); yes there were subtler hints of cherries and flowers here (more strain), under which moved the darker scent of burnt brown sugar – but there was nothing overly dramatic that grabbed my snoot, no I-see-Vishnu moment, no heavenly chorus of angel who should attend the opening of such a purportedly premium product. What was self evident was, as I’ve noted, that damned scent.

The citrus background was more muted than in the XO, but still far too prevalent and bashed the others into a sort of torpid insensibility – it’s like an orange Chuck Norris came through the joint, belted out a roundhouse kick to the face, and all the other smells fell down, twitching feebly.

The palate? No redemption, I’m afraid, and by now I was wondering – what the hell was going on? Did some disgruntled vet pop a few hundred rinds into the still? The liquid was thicker and oilier than other rums I’ve tried, and coated the tongue like it wanted to be a delivery system for a few fascinating flavours the master blender had pulled out of his hat; there was a sweet and lasting flavor, but what the hell was it? A liqueur?

I was tasting a smoothly sweetish spirit and a commingled taste of various almost impossible-to-discern elements dominated by orange marmalade flavor. Again I got the annoyingly faint background tastes the nose had hinted at, without any of them having the courage to tek front and show us who was boss. The floral scents dimmed more than shimmered, the caramel-molasses and burnt sugar taste faded almost entirely, and what I was left with was something that wasn’t sure what it wanted to be…too sweet for a rum, not complex enough for a high-end. Excuse me fellas. I thought there was supposed to be rums here. This was what two hundred drops of my sweat had bought?

And don’t believe I was entirely mollified by the excellent fade, the only thing I don’t have a whinge about. The 1623 goes down very well, without serious burn or scratch, and even a non-rum-drinker might like that part: my 72 year old father-in-law took a sniff, smacked his gums, sipped it down and allowed it may even eclipse the standard Russian rotgut he preferred (talk about damning with faint praise there), while observing it had too much sugar, as if I should shoot off to Anguilla immediately and take them to task about the matter. In fact, I did send an email down there (and to Patron) asking about the taste and the sugar, which has thus far remained unanswered.

Pyrat’s Cask 1623, also known as Cask 23 for people who can’t be bothered to write the whole thing, is a blend of rums aged up to 40 years. Note the careful phrasing on the Pyrat website: “We distill the dark amber spirit in limited quantities, ageing its smooth distinctive blend of premium Caribbean rums in oak barrels for up to 40 years.” What that means to me is that the oldest rum in the blend is 40 years old (not the youngest) and there’s no information regarding what proportion is that old. About all I’ve read online is that the average age of the blends of pot-still and column-still rums that make the 1623, is 23 years. Even the barrels are a bit dodgy – I’ve heard of the usual bourbon barrels, of course, and rumours of barrels that once held orange liqueur. So maybe that’s what it is. Caveat Emptor.

Honesty compels me to note that Pyrat’s 1623 won the 2007 Ministry of Rum tasting competition, but speaking for this puppy, I can only wonder how on earth that happened. Let me put it to you this way: if you were handing out prizes for distinctiveness, then Bundie, Old Port, Pyrat’s XO and maybe Legendario would come out top – you could taste them blind and know what you were getting because they are so unique in taste, so different: but that difference does not translate into real quality, and frankly, I think Pyrat’s is teetering on the edge of not being a rum at all, what with all that extra stuff they must be chucking into the ageing barrels with such languid insouciance.

So there we have it. Unimpressive. I know I sound a little miffed, perhaps even a shade snarky. But I’m feeling let down, more than a little annoyed. Actually, I’m plenty mad. This rum is such a disappointment – it’s a forty dollar rum in a hundred dollar package, selling for two hundred. Some might argue that I like the sugar-caramel-molasses taste in my rums, and just as I like that taste, so there are others out there who prefer peats, and others who will like orange or sherry or what have you. No harm no foul. Yet, I disagree: the whole selling point of Islay whiskies is that unmistakeable peatiness; with rums it’s the core of caramel and burnt sugar enhanced by the varying notes imparted by climate (Bundie or Old Port spring to mind immediately), distillation techniques, ageing and the barrels used. In the top end of rums, there is an underlying harmony, a sort of zen marriage of all good things that come together like a Porsche 911 GT3. Sure it blasts off with you, but in a good way. All is in balance. You don’t mind getting your faced ripped off at 6500 rpm and 200mph because you are utterly ensorcelled by the sheer unbridled harmony of the components meshing together like they were lubricated in distilled angels’ tears.

And that’s not the case here. We’ve been sold on a marketing gimmick. We’ve been fed on rarity, a carefully parsed age statement, and price (and a really odd dearth of online reviews I have difficulty comprehending – what, has no-one tasted this thing?). When I tried the English Harbour 1981, the Appleton 30 and Master’s Blend, the El Dorado 21 and 25, the G&M Longpond 1941, I could taste the underlying structural complexity and efforts to both smoothen and balance off the competing flavours. Here, we have an inexplicable central taste of citrus that advertises its ego from the get go, practically drowns out all other flavours, and to my mind is only marginally redeemed by an extraordinary smoothness. Ultra-premium? Yeah, it’s about as ultra-premium as a garage sale with one good item in it.

For a rum this expensive and positioning itself at the top of the rum chain, I’d suggest that they stop messing about with the Hoti medallion…and replace it with one that bears the imprint of the patron saint of shell games and snake oil sellers.

(#080)(Unscored)

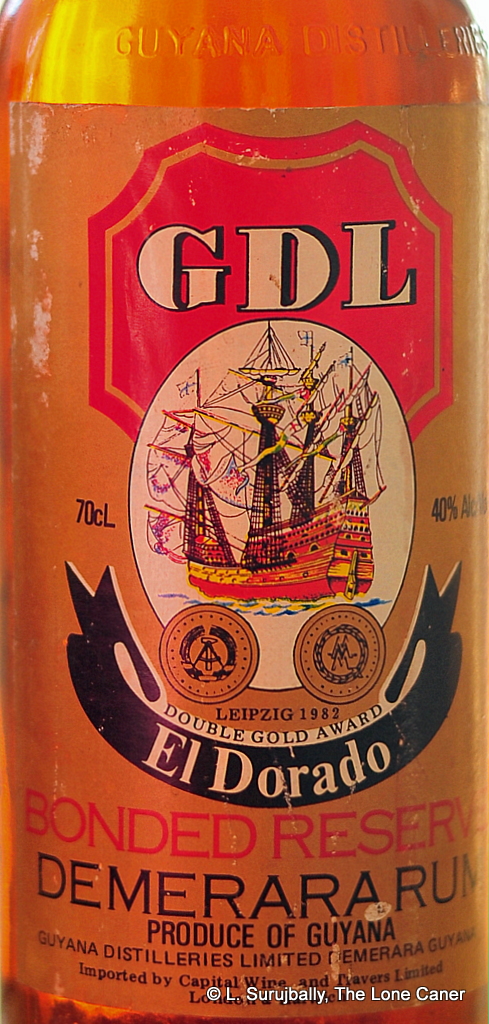

Tasting the Bonded Reserve raised all sorts of questions, and for anyone into Mudland rums, the first one had to be the one you’re all thinking of: from which still did it come? I didn’t think it was any of the wooden ones – there was none of that licorice or fruity intensity here that so distinguishes them. It was medium to light bodied in texture, very feebly sweet, and presented initially as dry – I’d suggest it was a column still product. Prunes, coffee, some burnt sugar, nougat and caramel, more of that faint leather and smoke background, all rounded out with the distant, almost imperceptible murmuring of citrus and crushed walnuts, nothing special. The finish just continued on these muted notes of light raisins and molasses and toffee, but too little of everything or anything to excite interest beyond the historical.

Tasting the Bonded Reserve raised all sorts of questions, and for anyone into Mudland rums, the first one had to be the one you’re all thinking of: from which still did it come? I didn’t think it was any of the wooden ones – there was none of that licorice or fruity intensity here that so distinguishes them. It was medium to light bodied in texture, very feebly sweet, and presented initially as dry – I’d suggest it was a column still product. Prunes, coffee, some burnt sugar, nougat and caramel, more of that faint leather and smoke background, all rounded out with the distant, almost imperceptible murmuring of citrus and crushed walnuts, nothing special. The finish just continued on these muted notes of light raisins and molasses and toffee, but too little of everything or anything to excite interest beyond the historical.