In an ever more competitive market – and that includes French island agricoles – every chance is used to create a niche that can be exploited with first-mover advantages. Some of the agricole makers, I’ve been told, chafe under the strict limitations of the AOC which they privately complain limits their innovation, but I chose to doubt this: not only there some amazing rhums coming out the French West Indies within the appellation, but they are completely free to move outside it (as Saint James did with their pot still white) – they just can’t put that “AOC” stamp of conformance on their bottle, and making one rum outside the system does not invalidate all the others they can and do make within it.

In an ever more competitive market – and that includes French island agricoles – every chance is used to create a niche that can be exploited with first-mover advantages. Some of the agricole makers, I’ve been told, chafe under the strict limitations of the AOC which they privately complain limits their innovation, but I chose to doubt this: not only there some amazing rhums coming out the French West Indies within the appellation, but they are completely free to move outside it (as Saint James did with their pot still white) – they just can’t put that “AOC” stamp of conformance on their bottle, and making one rum outside the system does not invalidate all the others they can and do make within it.

This particular rhum illustrates the point nicely. It’s an AOC rhum made from a very specific variety of cane coloured gray-purple (don’t ask me how that got translated to ‘blue’) which is apparently due to an abundance of wax on the stem. It’s been used by Habitation Clément since 1977 and supposedly has great aromatics and is richer than usual in sugar, and is completely AOC-approved.

Clément has been releasing the canne bleue varietal rhums in various annual editions since about 2000. Its signature bottle has gone through several iterations and the ice blue design has become, while not precisely iconic, at least recognizable – you see it and you know it’s a Clément rhum of that kind you’re getting. Curiously, for all that fancy look, the rum retails for relative peanuts – €40 or less. Maybe because it’s not aged, or the makers feared it wouldn’t sell at a higher price point. Maybe they’re still not completely sold on the whole unaged white rhum thing, even if the clairins are doing great business, and unaged blancs have gotten a respect of late (especially in the bar and cocktail circuit), which they never enjoyed before

What other types of cane Habitation Clément uses is unknown to me. They have focused on this one type to build a small sub-brand around and it’s hard to fault them for the choice, because starting just with the nose, it’s a lovely white rum, clocking in at a robust 50% ABV. What I particularly liked about it is its freshness and clarity: it reminds me a lot of of Neisson’s 2004 Single Cask (which costs several times as much), just a little lighter. Salty wax notes meld nicely with brine and tart Turkish olives to start. Then the crisp peppiness of green apples and yoghurt, sugar water, soursop and vinegar-soaked cucumber with a wiri-wiri pepper chopped into it. The mix of salt and sour and sweet and hot is really not bad.

It’s sharp on the initial tasting – that levels down quickly. It remains spicy-warm from there on in, and is mostly redolent of fresh, sweet and watery fruit: so, pears, ripe green apples, white guavas. There are notes of papaya, florals, loads of swank, avocados, some salt, all infused with lemon grass, ginger and white pepper. The clarity and crispness of the nose is tempered somewhat as the tasting goes on, allowing softer and less aggressive flavours to emerge, though they do stay on the edges and add background rather than hogging the whole stage. The finish is delicate and precise; short, which is somewhat surprising, yet flavourful – slight lemon notes, apricots, cinnamon and a touch of unsweetened yoghurt.

So, what to make of this econo-budget white rhum? Well, I think it’s really quite good. The Neisson I refer to above was carefully aged, more exclusive, cost more…and yet scored the same — though it was for different aspects of its profile, and admittedly its purpose for being is also not the same as this one. I like this unaged blanc because of its sparkling vivacity, its perkiness, its rough and uncompromising nature which masks an unsuspected complexity and quality. There are just so many interesting tastes here, jostling around what is ostensibly a starter product (based on price if nothing else) — this thing can spruce up a mixed drink with no problem, a ti-punch for starters, and maybe a daiquiri for kicks.

I don’t know what aspects of its profile derive from that bleue cane specifically because so far in my sojourn through The Land of Blanc I’ve experienced so many fantastic rhums and each has its own peculiar distinctiveness. All I can say is that the low pricing here suggests a rhum that lives and dies at the bottom of the scale…but you know, it really shouldn’t be seen that way. It’s far too good for that.

(#796)(85/100)

Other Notes

- Production is limited to between 10,000 and 20,000 bottles a year, depending on the harvest. Not precisely a limited edition but for sure something unique to each year.

- Thanks to Etienne Sortais, who provided me with the sample, insisting I try the thing. He was certainly right about that.

I was really and pleasantly surprised by how well it presented, to be honest. For a standard strength rhum, I expected less, but its complexity and changing character eventually won me over. Looking at others’ reviews of rhums in Reimonenq’s range I see similar flip flops of opinion running through them all. Some like one or two, some like that one more than that other one, there are those that are too dry, too sweet, too fruity (with a huge swing of opinion), and the little literature available is a mess of ups and downs.

I was really and pleasantly surprised by how well it presented, to be honest. For a standard strength rhum, I expected less, but its complexity and changing character eventually won me over. Looking at others’ reviews of rhums in Reimonenq’s range I see similar flip flops of opinion running through them all. Some like one or two, some like that one more than that other one, there are those that are too dry, too sweet, too fruity (with a huge swing of opinion), and the little literature available is a mess of ups and downs.

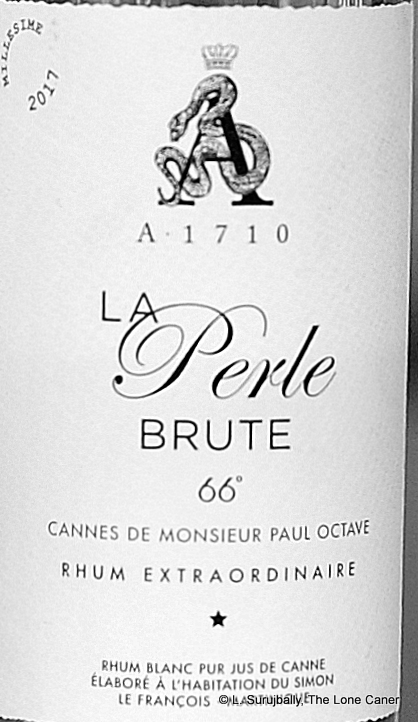

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.

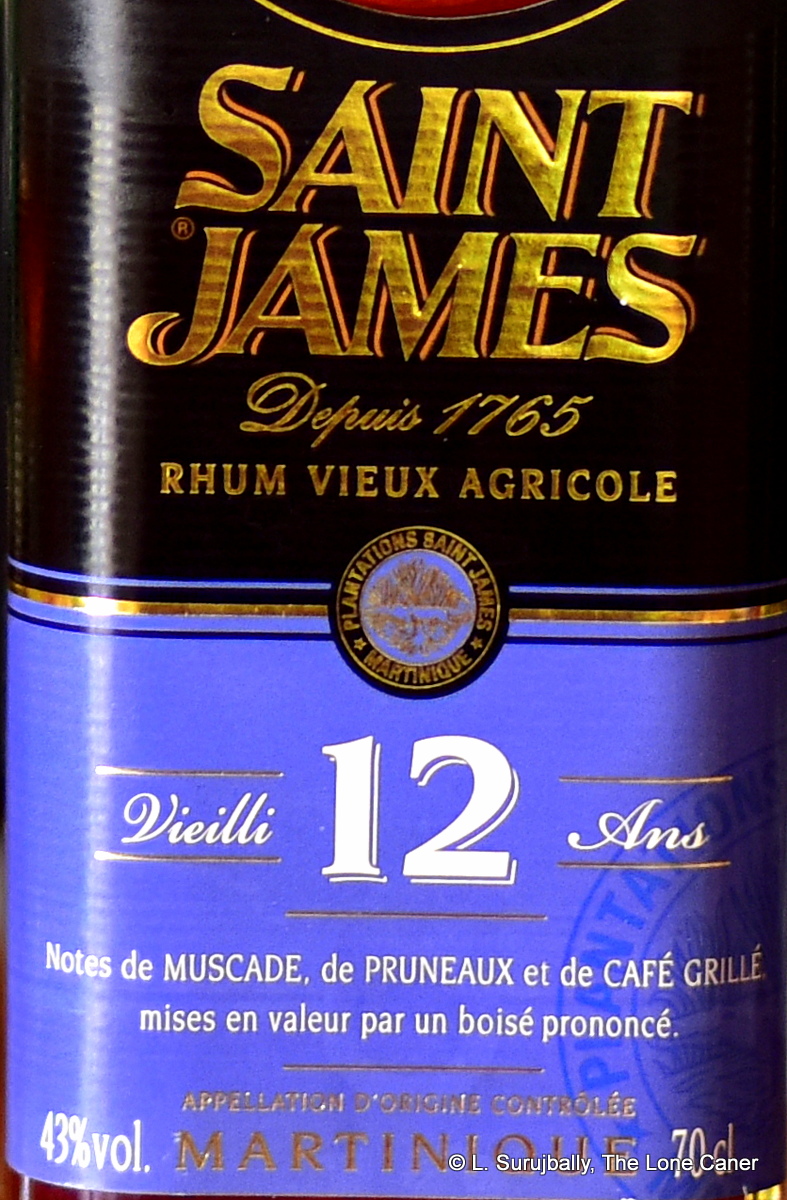

Certainly the 2003 10 YO does its next-best relative the

Certainly the 2003 10 YO does its next-best relative the

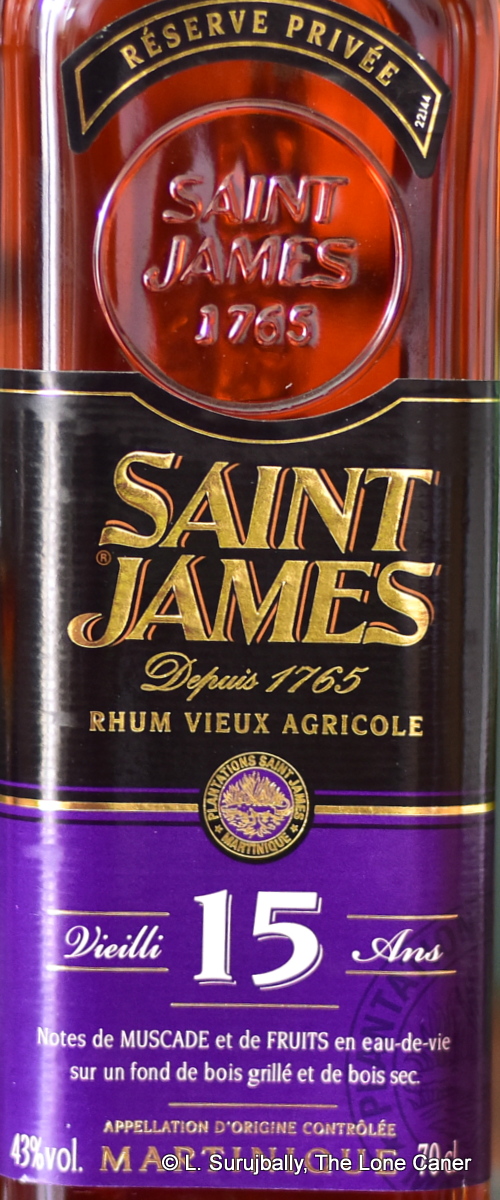

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

To some extent, it has a lighter nose than the luscious

To some extent, it has a lighter nose than the luscious

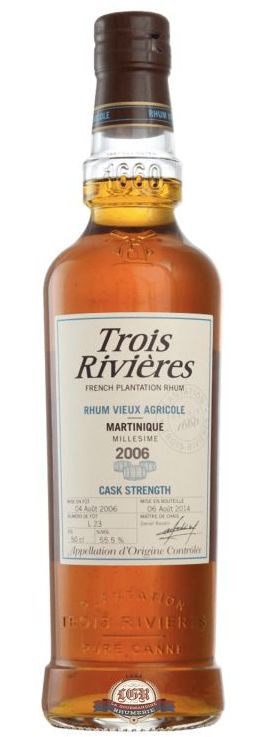

The Trois Rivières Brut de fût Millésime 2006 (which is its official name) is relatively unusual: it’s aged in new American oak barrels, not Limousin, and bottled at cask strength, not the more common 43-48%. And that gives it a solidity that elevates it somewhat over the standards we’ve become used to. Let’s start, as always, with the nose — it just becomes more assertive, and more clearly defined…although it seems somehow gentler (which is quite a neat trick when you think about it). It is redolent of caramel and vanilla first off, and then adds green apples, tart yoghurt, pears, white guavas, watermelon and papaya, and behind all that is a delectable series of herbs – rosemary, dill, even a hint of basil and aromatic pipe tobacco.

The Trois Rivières Brut de fût Millésime 2006 (which is its official name) is relatively unusual: it’s aged in new American oak barrels, not Limousin, and bottled at cask strength, not the more common 43-48%. And that gives it a solidity that elevates it somewhat over the standards we’ve become used to. Let’s start, as always, with the nose — it just becomes more assertive, and more clearly defined…although it seems somehow gentler (which is quite a neat trick when you think about it). It is redolent of caramel and vanilla first off, and then adds green apples, tart yoghurt, pears, white guavas, watermelon and papaya, and behind all that is a delectable series of herbs – rosemary, dill, even a hint of basil and aromatic pipe tobacco.

Okay so, on to palate. Straw yellow in the glass, it was softer and less intense, which, for a forty percenter, was both good and bad. Here the grassy and herbal notes took on more prominence, as did citrus, some tart unsweetened yoghurt, honey and cane juice. The youth was evident in the slight sharpness and lack of real roundness – the two years of ageing had

Okay so, on to palate. Straw yellow in the glass, it was softer and less intense, which, for a forty percenter, was both good and bad. Here the grassy and herbal notes took on more prominence, as did citrus, some tart unsweetened yoghurt, honey and cane juice. The youth was evident in the slight sharpness and lack of real roundness – the two years of ageing had  In 1923 La Mauny was sold to Théodore and Georges Bellonnie who enlarged and brought in new facilities such as a distillation column, new grinding mills and a steam engine. The distillery expanded hugely thanks to increased output and good marketing strategies and La Mauny rhums began to be exported around 1950. In 1970, after the Bellonnie brothers had both passed away, the Bordeaux traders and old-Martinique family of Bourdillon teamed up with Théodore Bellonnie’s widow and created the BBS Group. The company grew strongly, launching on the French market in 1977. Jean Pierre Bourdillon, who ran the new group, undertook to modernize La Mauny. He began by reorganizing the fields in order to make them accessible to mechanical harvesting and built a new distillery in 1984 (with a fourth mill, a three column still and a new boiler) a few hundred meters from the old one, increasing the cane crushing capacity and buying the equipment of the Saint James distillery in Acaiou, unused since 1958.

In 1923 La Mauny was sold to Théodore and Georges Bellonnie who enlarged and brought in new facilities such as a distillation column, new grinding mills and a steam engine. The distillery expanded hugely thanks to increased output and good marketing strategies and La Mauny rhums began to be exported around 1950. In 1970, after the Bellonnie brothers had both passed away, the Bordeaux traders and old-Martinique family of Bourdillon teamed up with Théodore Bellonnie’s widow and created the BBS Group. The company grew strongly, launching on the French market in 1977. Jean Pierre Bourdillon, who ran the new group, undertook to modernize La Mauny. He began by reorganizing the fields in order to make them accessible to mechanical harvesting and built a new distillery in 1984 (with a fourth mill, a three column still and a new boiler) a few hundred meters from the old one, increasing the cane crushing capacity and buying the equipment of the Saint James distillery in Acaiou, unused since 1958.

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The full and rather unwieldy title of the rum today is the Chantal Comte Rhum Agricole 1975 Extra Vieux de la Plantation de la Montagne Pelée, but let that not dissuade you. Consider it a column-still, cane-juice rhum aged around eight years, sourced from Depaz when it was still André Depaz’s property and the man was – astoundingly enough in today’s market – having real difficulty selling his aged stock. Ms. Comte, who was born in Morocco but had strong Martinique familial connections, had interned in the wine world, and was also mentored by Depaz and Paul Hayot (of Clement) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Martinique was suffering from overstock and poor sales.. And having access at low cost to such ignored and unknown stocks allowed her to really pick some amazing rums, of this is one.

The full and rather unwieldy title of the rum today is the Chantal Comte Rhum Agricole 1975 Extra Vieux de la Plantation de la Montagne Pelée, but let that not dissuade you. Consider it a column-still, cane-juice rhum aged around eight years, sourced from Depaz when it was still André Depaz’s property and the man was – astoundingly enough in today’s market – having real difficulty selling his aged stock. Ms. Comte, who was born in Morocco but had strong Martinique familial connections, had interned in the wine world, and was also mentored by Depaz and Paul Hayot (of Clement) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Martinique was suffering from overstock and poor sales.. And having access at low cost to such ignored and unknown stocks allowed her to really pick some amazing rums, of this is one.

Ah but when sipped, all that changes, and the clodhoppers go away and it dons a pair of ballet slippers. It’s stunningly fragrant, not quite delicate – that ballerina does have an extra pound or two – very firm and robust in flavour profile. Just on the first sip you can taste flowers, pears, papaya, honey, vanilla, raisins, grapes, all pulled together with a delectable light and salty note. There are nice citrus hints, a tease from the oak, ginger and cinnamon, and overall, it sips as nicely as it mixes. The finish is well handled, though content to play it safe – things are beginning to quieten down here, and it fades quietly without stomping on you – and certainly nothing new or original comes into being; the rhum is content to follow where the nose and palate led – fruits, pineapple, spices, ginger, vanilla – without breaking any new ground.

Ah but when sipped, all that changes, and the clodhoppers go away and it dons a pair of ballet slippers. It’s stunningly fragrant, not quite delicate – that ballerina does have an extra pound or two – very firm and robust in flavour profile. Just on the first sip you can taste flowers, pears, papaya, honey, vanilla, raisins, grapes, all pulled together with a delectable light and salty note. There are nice citrus hints, a tease from the oak, ginger and cinnamon, and overall, it sips as nicely as it mixes. The finish is well handled, though content to play it safe – things are beginning to quieten down here, and it fades quietly without stomping on you – and certainly nothing new or original comes into being; the rhum is content to follow where the nose and palate led – fruits, pineapple, spices, ginger, vanilla – without breaking any new ground.

Light amber in colour and bottled at 43%, it certainly did not nose like your favoured Caribbean rum. It smelled initially of congealed honey and beeswax left to rest in an old unaired cupboard for six months – that same dusty, semi-sweet waxy and plastic odour was the most evident thing about it. Letting it rest produced additional aromas of brine, olives and ripe mangoes in a pepper sauce. Faint vanilla and caramel – was this perhaps made from jaggery, or added to after the fact? Salty cashew nuts, fruit loops cereal and that was most or less it – a fairly heavy, dusky scent, darkly sweet.

Light amber in colour and bottled at 43%, it certainly did not nose like your favoured Caribbean rum. It smelled initially of congealed honey and beeswax left to rest in an old unaired cupboard for six months – that same dusty, semi-sweet waxy and plastic odour was the most evident thing about it. Letting it rest produced additional aromas of brine, olives and ripe mangoes in a pepper sauce. Faint vanilla and caramel – was this perhaps made from jaggery, or added to after the fact? Salty cashew nuts, fruit loops cereal and that was most or less it – a fairly heavy, dusky scent, darkly sweet.

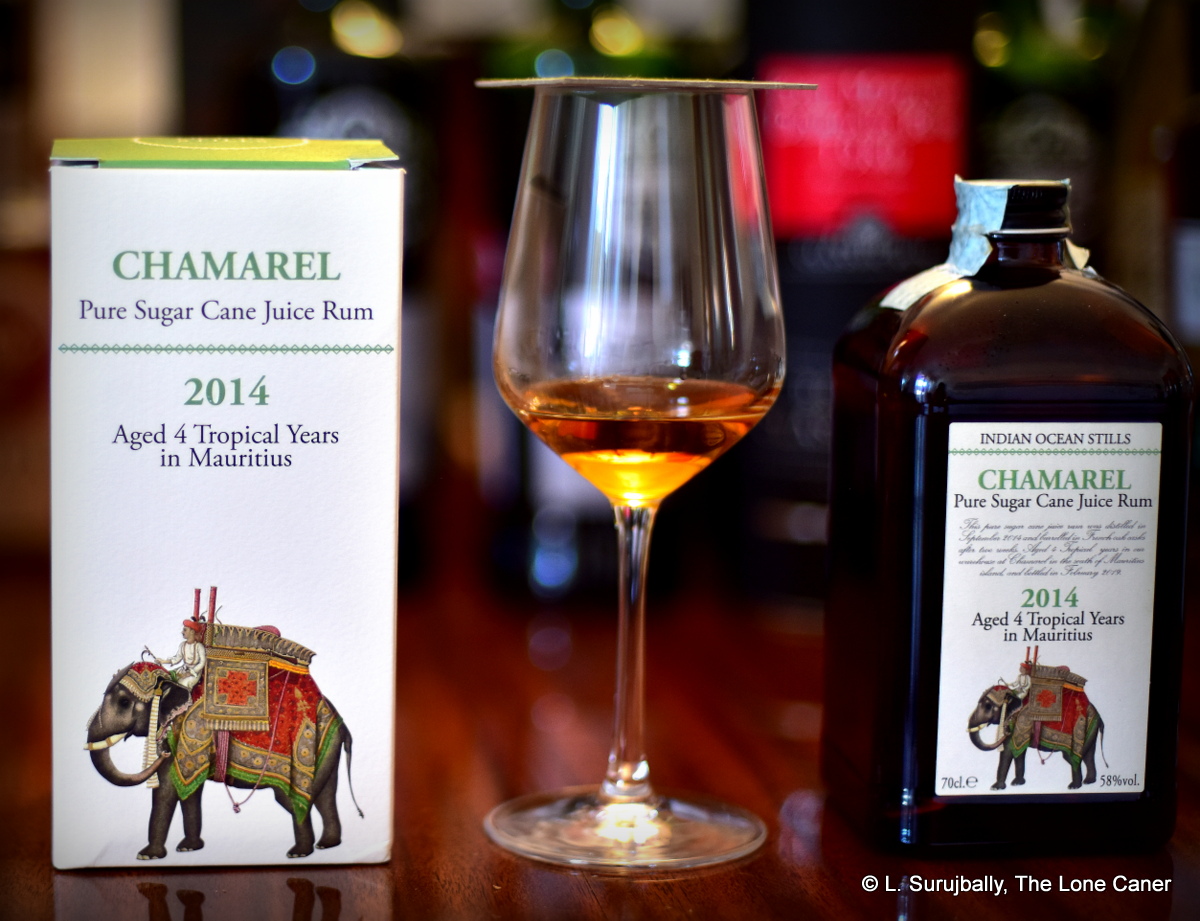

Brief stats: a 4 year old rum distilled in September 2014, aged in situ in French oak casks and bottled in February 2019 at a strength of 58% ABV. Love the labelling and it’s sure to be a fascinating experience not just because of the selection by Velier, or its location (we have tried few rums from there though those

Brief stats: a 4 year old rum distilled in September 2014, aged in situ in French oak casks and bottled in February 2019 at a strength of 58% ABV. Love the labelling and it’s sure to be a fascinating experience not just because of the selection by Velier, or its location (we have tried few rums from there though those