As noted in the Mount Gay XO revisit, that company ceded much of the intellectual and forward-looking territory of the Bajan rum landscape to Foursquare — in the last ten years, correctly sensing the shifting trends and tides of the rumworld, Richard Seale bet the company’s future on aspects of rum making that had heretofore been seen as artistic, even bohemian touches best left for the snooty elite crowd of the Maltsters with their soft tweed caps, pipes, hounds, and benevolent fireside sips of some obscure Scottish tipple. He went for a more limited and experimental approach, assisted in his thinking by collaboration with one of the Names of Rum. This has paid off handsomely, and Foursquare is now the behemoth of Barbados, punching way above its weight in terms of influence, leaving brands such as Cockspur, St. Nicholas Abbey and Mount Gay as big sellers, true, but not as true innovators with real street cred (WIRD is somewhat different, for other reasons).

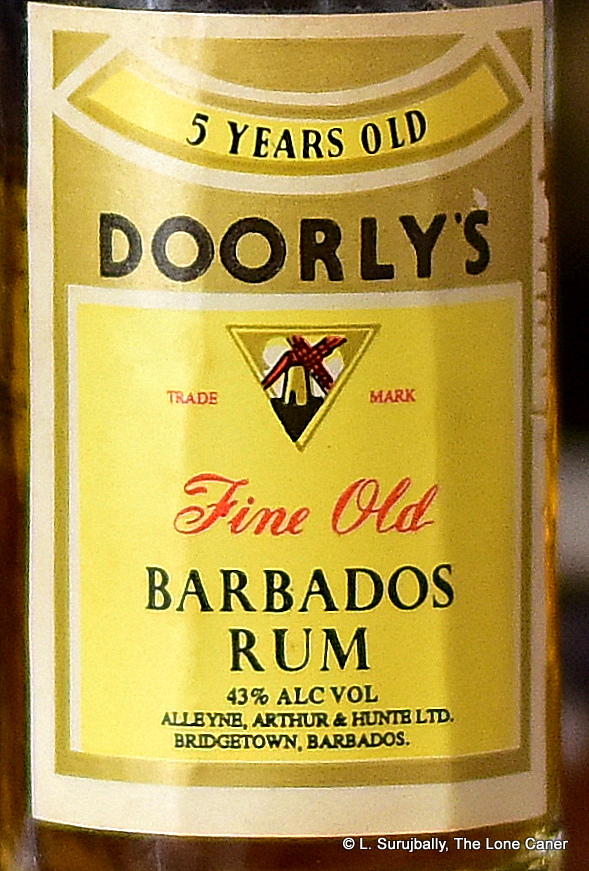

Now, I make no apologies for my relative indifference to Foursquare’s current line of Doorly’s rum – that’s a personal preference of mine and a revisit to the 10 and 12 year olds in 2017 and again in 2018 (twice!) didn’t change it one iota, though the 14 YO issued at somewhat higher strength in 2018 looks really interesting. I remain of the opinion that they’re rums from yesteryear that rank higher in memory than actuality; which won’t disqualify them from maybe being key rums in their own right, mind you….just not yet. But as I tried more and more Bajans in an effort to come to grips with the peculiarity of the island’s softer, more easygoing rum, so different from the fierce pungency of Jamaica, the woodsy warmth of Guyana, the clear quality of St Lucia, the lighter Cuban-style rums or the herbal grassiness of any French West Indian agricole, it seemed that there was another key rum of the world lurking in Little England, and I’d simply been looking with too narrow a focus at single candidates.

I don’t believe it’s too soon after their introduction to make such a claim, and argue that leaving aside Habitation Velier collaborations like the Triptych, Principia or the 2006 ten year old, the real new Key Rums from the island are the Exceptional Cask Series made by Foursquare. They are quietly high-quality, issued in quantity, still widely available – every week I see four or five posts on FB that someone has picked up the Criterion or the Zinfadel or the Port Cask – reasonably affordable (Richard Seale has made a point of keeping costs down to the level consumers can actually afford) and best of all, they are consistently really good.

Richard Seale – for to speak of him is to speak of Foursquare – has made a virtue out of what, in the previous decade of light-rum preferences, could have been a fatal regulatory block – the inability of Bajan rum makers to adulterate their rums (the Jamaicans operate under similar restrictions). This meant that while other places could sneak some caramel or sugar or vanilla or glycerol into their rums (all in the name of smoothening out batch variation and enhancing quality, when it wasn’t “our centuries old secret family recipe” or a “traditional method”), and deny for decades that this was happening, Barbados was forced to issue purer, drier rums that did not always appeal to sweet-toothed, smooth-rum-loving general public, especially in North America. It was at the stage where importers were actually demanding that island rum producers make smooth, sweet and light rums if they wanted to export any.

What Foursquare did was to use all the rum-making options available to them – experimenting with the pot still and column still blends, barrel strategy, multiple maturations, various finishes, in situ ageing – and market the hell out of the result. None of this would have mattered one whit except for the intersection of several major new forces in the rumiverse: the drive and desire for pure rums (i.e., unadulterated by additives); social media forcing disclosure of such additives and educating consumers into the benefits of having none; the rise and visibility of independents and their more limited-release approach; and the market slowly shifting to at least considering rums that were issued at full proof, and hell, you can add the emergent trend of tropical ageing to the mix. Foursquare rode that wave and are reaping the benefits therefrom. And let’s not gild the lily either – the rums they make in the Exceptional Series are quite good…it’s like they were making plain old Toyotas all the while, then created a low-cost Lexus for the budget-minded cognoscenti.

Now let’s be clear – if one considers a really pure rum made as being entirely from one country (or island), from a specific pot or column still, deriving from a single plantation or estate’s own sugar cane, molasses/juice, fermented on site, distilled on site, aged on site, then the Exceptional Series aren’t quite it, being very good blends of pot and column distillate, and made from molasses procured elsewhere. And while sugar and caramel are not added, the influence of wine or port or cognac barrels is not inconsiderable after so many years…which of course adds much to the allure. But I’m not a raging, hot-eyed zealot who wants rums to be stuck in some mythical past where only a very narrow definition of spirits qualifies as a rum – that stifles innovation and out of the box thinking and eventually quality such as is demonstrated here inevitably suffers. I’m merely pointing out this matter to comment that the Exceptionals aren’t meant to represent Barbados as a whole (though I imagine Richard wouldn’t mind it if they did) – they’re meant to define Foursquare, to snatch back the glory and the street cred and the sales from other Bajan makers, and from the European re-bottlers and independents who made profits over the decades with such releases, and which many believe should remain in the land of origin.

But all that aside, there’s another aspect to this which must be mentioned: perhaps my focus still remains to narrow when I speak of the ECS and the company and the island. In point of fact, given the incredible popularity and rabid fan appreciation for the series – outdone, perhaps, only by the mania for collaborations like the 2006, Triptych and its successors – it is entirely likely that the Exceptional Cask series is a Key Rum because the rums have to some extent had a global impact and strengthened trends which were started by The Age of Velier’s Demeraras, developed by Foursquare and now coming on strong in Jamaica – tropical ageing, no additives, cask strength. So forget Barbados…these rums have had an enormous influence far beyond the island. They are part of the emergent trend to produce rums that are aimed between the newbies and the ur-geek connoisseurs and won’t break the bank of either.

Perhaps this is why they have captured the attention of the global rum crowd so effectively – for the Exceptional Series rums to ascend in the estimation of the rum public so quickly and so completely as to eclipse (no pun intended) almost everything else from Barbados, says a lot. And although this is just my opinion, I think they will stand the test of time and take their place as rums that set a new standard for the distillery and the island. For that reason I decided not to take any one individual rum as a candidate for this series, but to include the entire set to date as “one” of the Key Rums of the World.

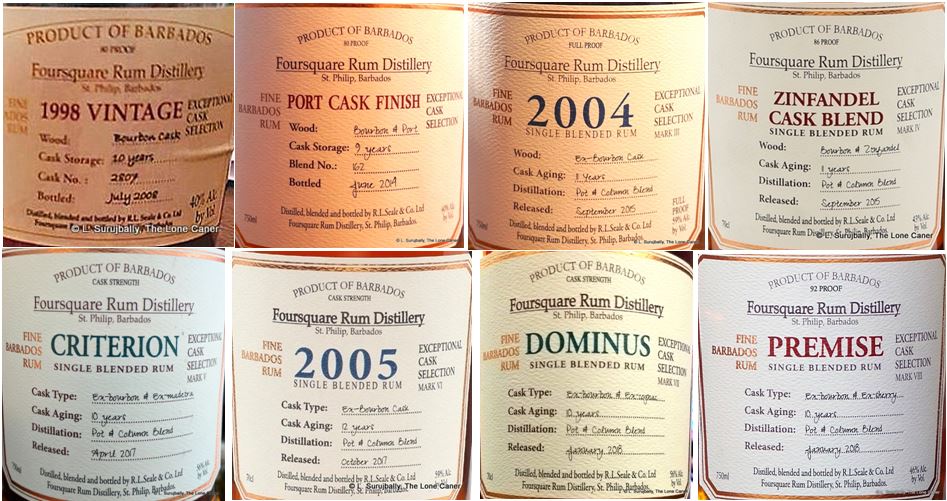

The Rums Supporting this Article, in 2018

Note – I have not reviewed them all formally (though I have tasting notes for most). All notes here are mine, whether published or unpublished.

Picture (c) Henrik Larsen, from FB

Mark I — “1998” 1998-2008 10 Year Old, Bourbon Cask, 40%, 15,000 bottles

This rum remains unacquired and untasted by me. Frankly I think that’s the case for most people, and even though the outturn was immense at 15k bottles worldwide, that was ten years ago, so it’s likely to only be found on the secondary market. That said, I suspect this was a toe in the water for Foursquare, it tested the market and sought to move in a new direction, perhaps copying the independents’ success without damaging the rep or sales of the RL Seale’s 10 YO, Rum 66 or Doorly’s lineup. The wide gap between 2008 and 2014 when the Port Cask came out suggests that some more twiddling with the gears and levers was required before Mark II came out the door, and Richard himself rather sourly grumbled that the importers forced him to make it 40% when in point of fact he wanted to go higher…but lacked the leverage at the time.

Mark II — “Port Cask Finish” 2005-2014 9YO, 3yr-Bourbon, 6yr-Port, Pot/Column Blend 40%, 30,000 bottles

Mark II — “Port Cask Finish” 2005-2014 9YO, 3yr-Bourbon, 6yr-Port, Pot/Column Blend 40%, 30,000 bottles

Six years passed between Mark I and Mark II, and a lot changed in that time. New bloggers, social media explosion, wide acknowledgement of the additives issue. With the Premise, the PCF Mark II remains the largest issue to date at 30,000 bottles worldwide. Not really a finished rum in the classic sense, but more a double aged rum, with the majority of the time spent in Port Casks.

N – Rubber and acetone notes, fading, then replaced by a smorgasbord of fruitiness: soft citrus of oranges, grapes, raisins, yellow mangoes, plums, vanilla, toffee; also some spices, cinnamon for the most part, and some cardamom.

P – Soft and relatively wispy. Prunes, vanilla, black cherries, caramel. Some coconut milk and bananas, sweetened yoghurt.

F – Short, smooth, breathy, quiet, unassuming. Some fruits and orange peel with salted caramel and bananas

T – Still lacked courage (again, the strength was an importers’ demand), but pointed the way to all the (better) Exceptional Cask Series rums that turned up in the subsequent years.

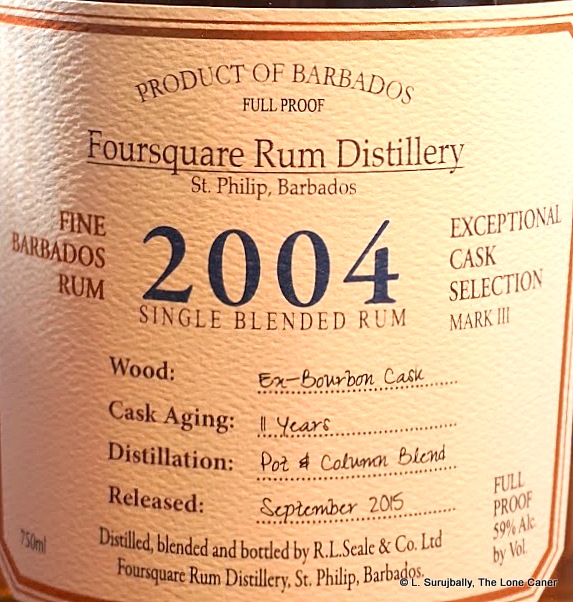

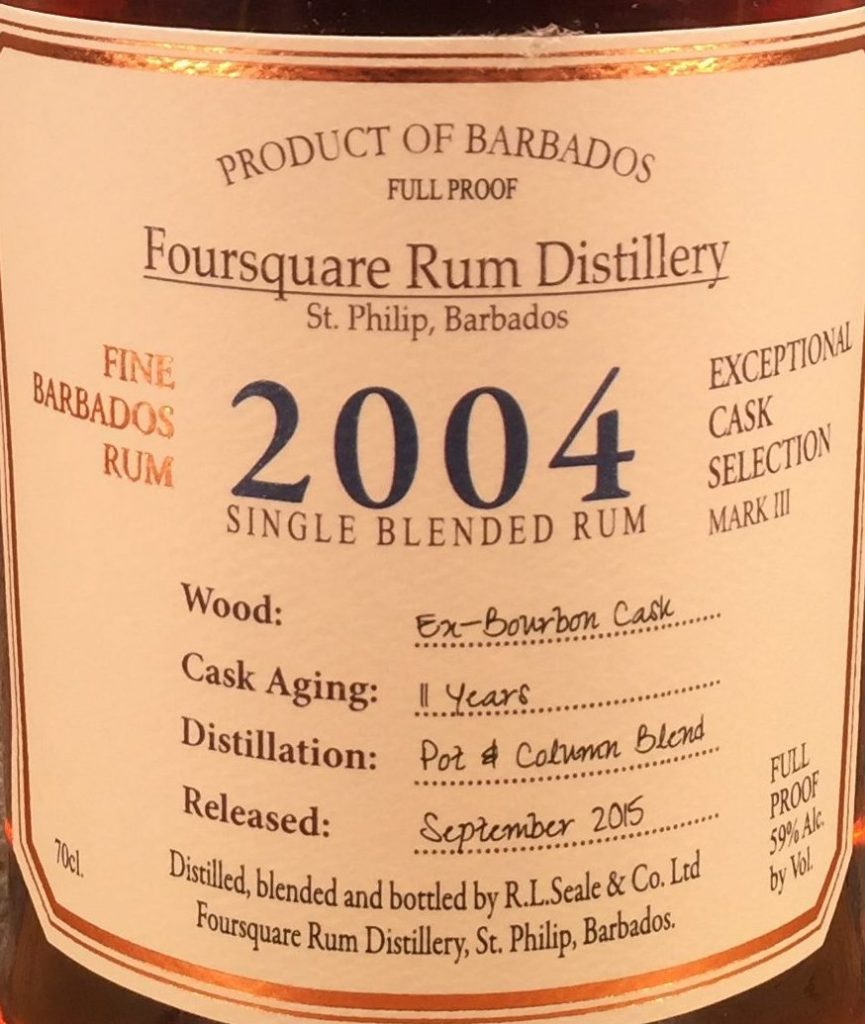

Mark III — “2004” 2004-2015 11 YO, Bourbon Cask, Pot/Column Blend, 59%, 24,000 bottles

Mark III — “2004” 2004-2015 11 YO, Bourbon Cask, Pot/Column Blend, 59%, 24,000 bottles

In 2015 two rums were issued at the same time, both 11 years old. This was the stronger one and its quality showed in no uncertain terms that Foursquare was changing the game for Barbados.

And the Velier connection was surely a part of the underlying production philosophy – we had been hearing for a year prior to the formal release that Richard Seale and Luca Gargano were turning up at exhibitions and fests to promote their new collaboration. Various favoured and fortunate tasters posted glowing comments on social media about the 2004 which showed that one didn’t need a massive and expensive marketing campaign to create buzz and hype

N – Clean and forceful, love that strength; wine, grapes, red grapefruit, fresh bread, laban, and bananas, coconut shavings, vanilla, cumin and cardamom. Retasting it confirmed my own comment “…invite(s) further nosing just to wring the last oodles of scent from the glass.”

P – Brine and red olives. Tastes smoothly of vanilla and coconut milk and yoghurt drizzled over with caramel and melted salt butter. Fruits, quite strong and intense – red grapes, red currants, cranberry juice – with further oak and kitchen spices (cumin and coriander).

F – Clear and crisp finish of oak, vanilla, olives, brine, toffee, and nougat.

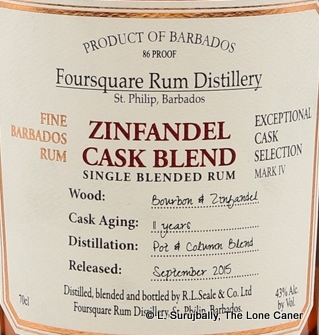

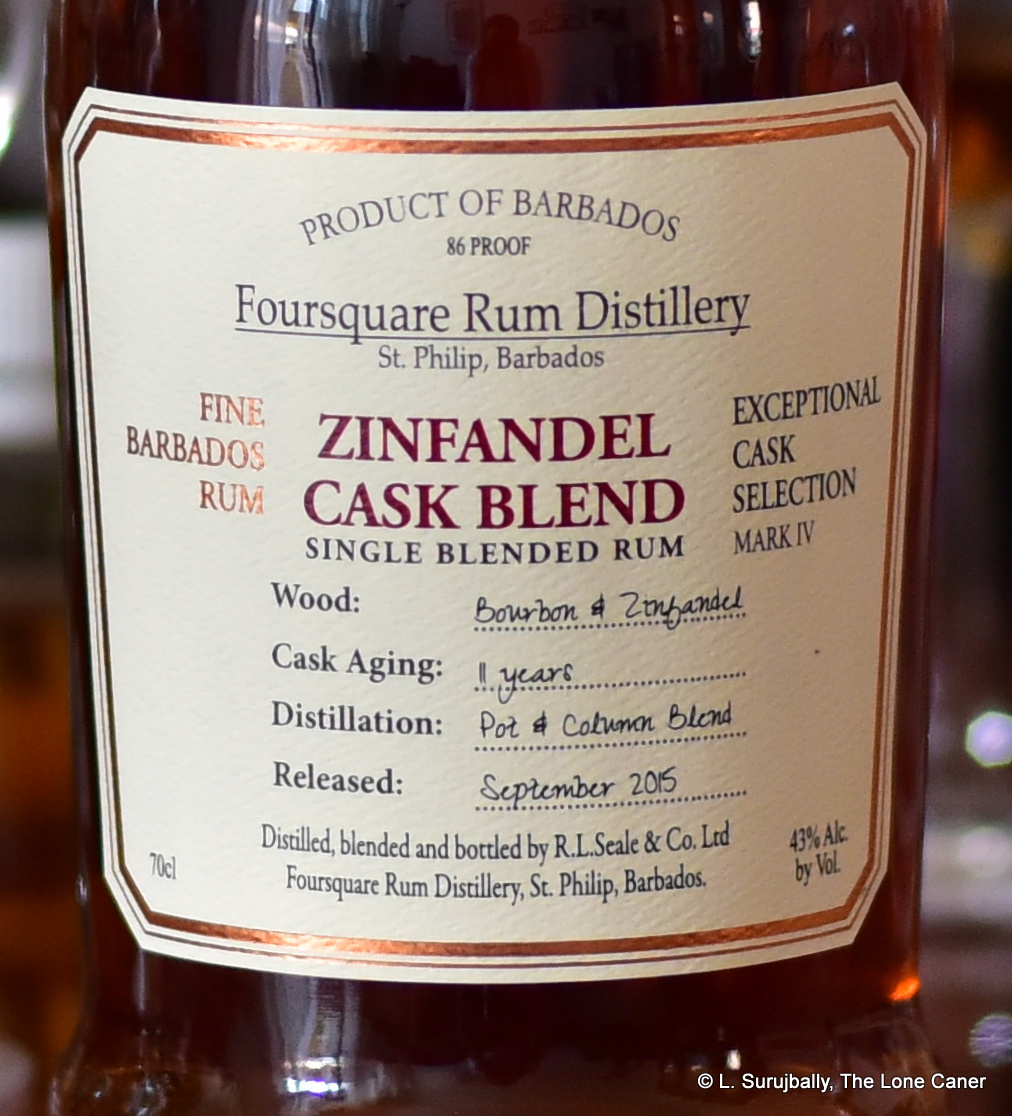

Mark IV — “Zinfadel” 2004-2015 11 YO Bourbon & Zinfadel casks, Pot/Column Blend 43%, 24,000 bottles

Mark IV — “Zinfadel” 2004-2015 11 YO Bourbon & Zinfadel casks, Pot/Column Blend 43%, 24,000 bottles

Not one of my favourites, really. Nice, but uncomplicated in spite of the Zinfadel secondary maturation. What makes it a standout is how much it packs into that low strength, which Richard remarked was a deliberate decision, not forced upon him by distributors – and that, if nothing else, showed that the worm was turning and he could call his own shots when it came to saying “I will issue my rum in this way.”

N – Light, with delicate wine notes, vanilla and white toblerone. A whiff of rotting bananas and fruits just starting to go. Tart yoghurt and sour cream and a white mocha, with fruits and other notes in the background – green grapes, raisins, dark bread, ginger and something sharp.

P – Opens with watery fruits (papaya, pears, watermelon, white gavas), then steadies out with cereals, coconut shavings. Also wine, tart red fruits – red currants, cranberries, grapes. Light and easy.

F – Quite pleasant, if short and relatively faint. fruits, coconut shavings, vanilla, milk chocolate, salted caramel, french bread (!!) and touch of thyme.

T – A marriage of two batches of rums: Batch 1 aged full 11 years in bourbon barrels; Batch 2 five years bourbon barrels then another six in ex-Zinfadel. The relative quantities of each are unknown.

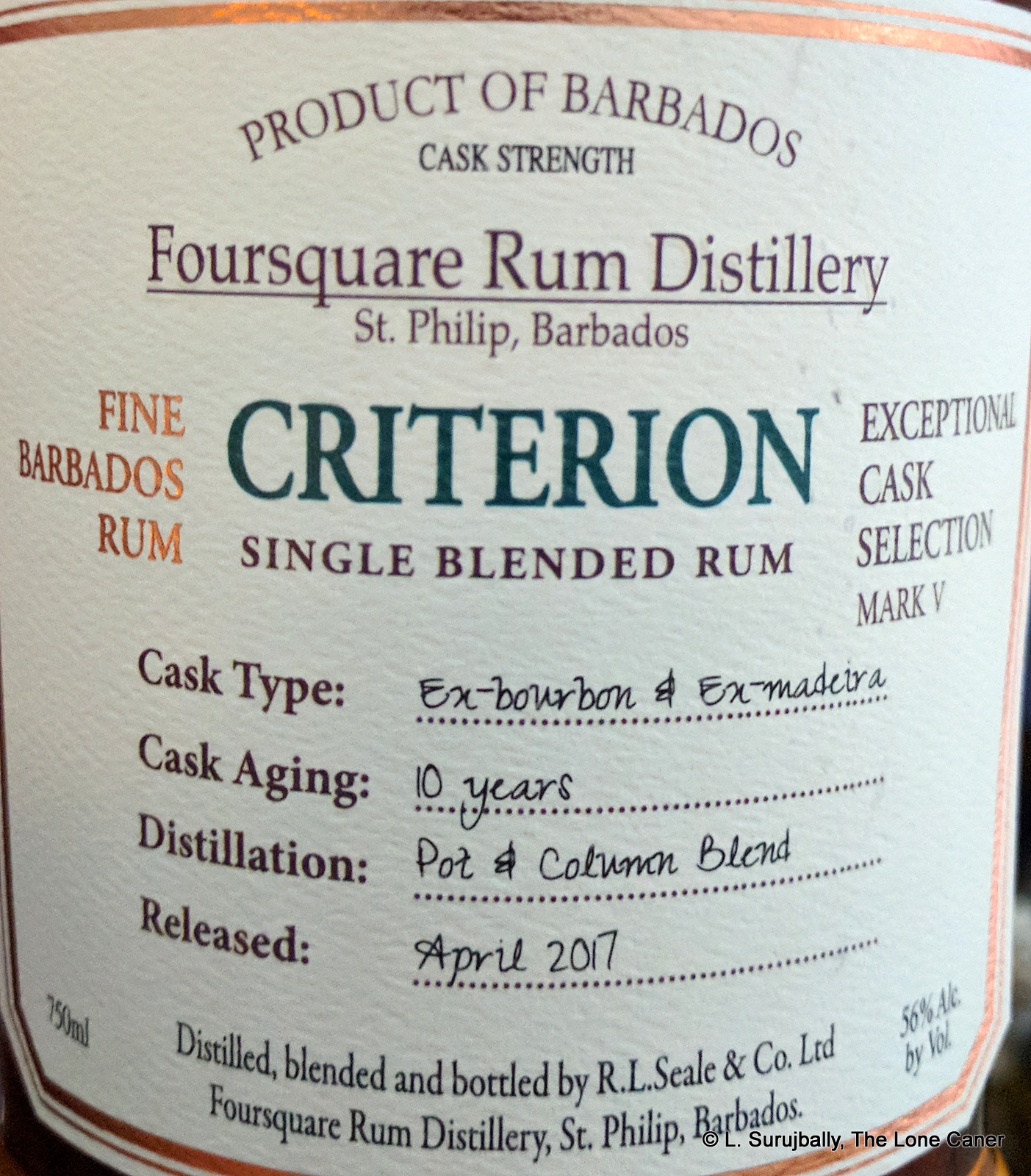

Mark V — “Criterion” 2007-2017 10 YO, 3yr-Bourbon, 7yr-Madeira, Pot Column Blend 56%, 4,000 bottles

Mark V — “Criterion” 2007-2017 10 YO, 3yr-Bourbon, 7yr-Madeira, Pot Column Blend 56%, 4,000 bottles

My feeling is that while the “2004” marked the true beginning of the really good Exceptionals, this is the first great ECS rum – all the ones before were merely essays in the craft before the mastery of Mark V kicked in the doors and blew off the roof, and all the others that came after built on the reputation this one garnered for itself. It was, to me, also the most individualistic of the various Marks, the one I have no trouble identifying from a complete lineup of Mark II to Mark VIII

N – Red wine, fruits, caramel in sumptuous abandon. Oak is there, fortunately held back; breakfast spices, burnt sugar, nutmeg, cloves. Also apples, grapes, pears, lemon peel, bitter chocolate and truffles.

P – Flambeed bananas, creme brulee, coffee, chocolate, it tastes like the best kind of late-night after-dinner bar-closer. Fruit jam, dates, prunes, crushed nuts (almonds) and the soft glide of honey in the background. Delectable

F – Long. Deep, dark, salt and sweet together. Prunes and very ripe cherries and caramel and coffee grounds..

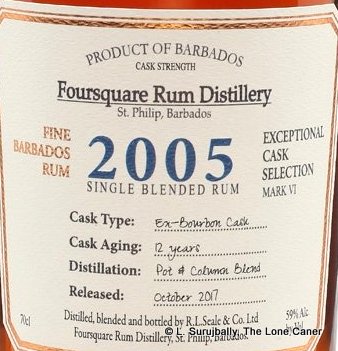

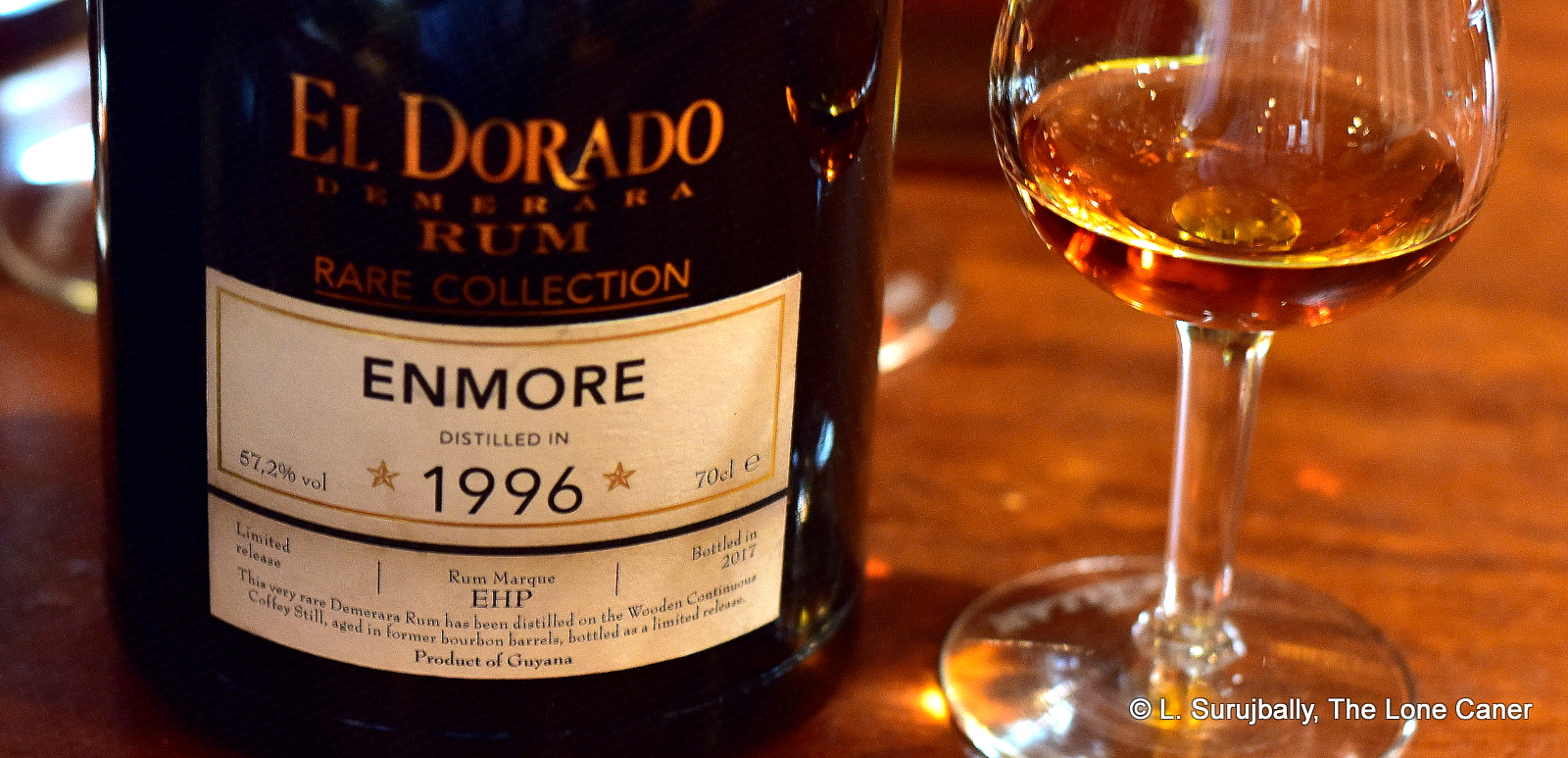

Mark VI — “2005” 2005-2017 12 YO, ex-bourbon, Pot/Column Blend, 59%, 24,000 bottles

Mark VI — “2005” 2005-2017 12 YO, ex-bourbon, Pot/Column Blend, 59%, 24,000 bottles

The 2005 was an alternative to the double maturation of the Criterion, being a “simple” single aged rum from bourbon casks, and was also a very good rum in its own way. A solid rum, if lacking something of what made its brother so special (to me, at any rate – your own mileage might vary).

N – Deep fruity notes of pears, plums, peaches in syrup (though without the sugar, ha ha). Just thick and juicy. Cream cheese, rye bread, cereals and osme cumin to give it a filip of lighter edge

P – Very nice but unspectacular: tart acidic and fleshy fruit tastes, mostly yellow mangoes, unripe peaches, red guavas, grapes raisins and a bit of red grapefruit. Also a delicate touch of thyme and rosemary, with vanilla and some light molasses to wind things up.

F – Long and aromatic, fruits again, rosemary, caramel and toffee.

T – Not crisp so much as solid and sleek, without bite or edge. It lacks individuality while being a complete rum package for anyone who simply wants a strong, well-assembled and tasty rum

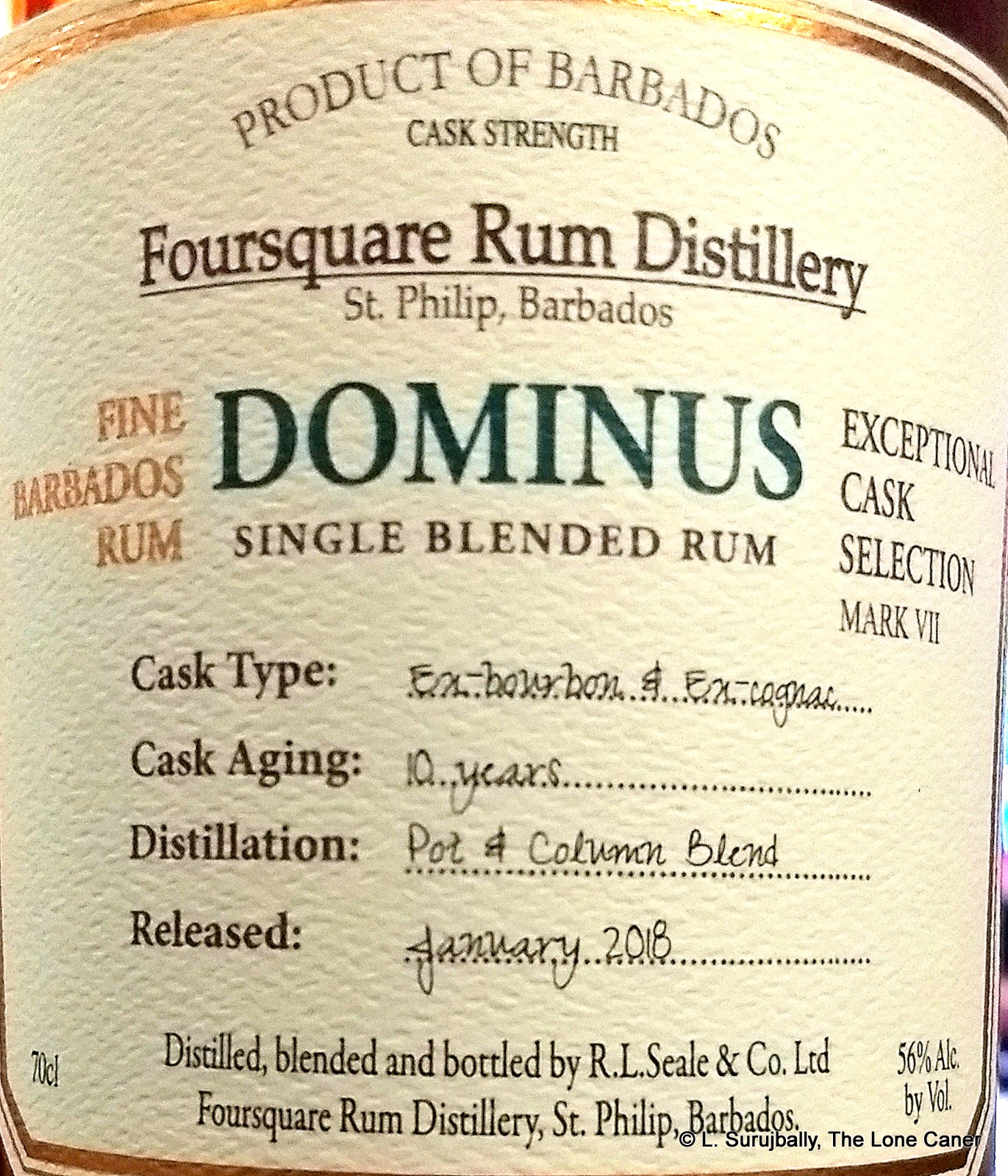

Mark VII — “Dominus” 2008-2018 10 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-cognac, Pot/Column Blend, 56%, 12,000 bottles

Mark VII — “Dominus” 2008-2018 10 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-cognac, Pot/Column Blend, 56%, 12,000 bottles

N – Dusty, herbal, leather, with smoke, vanilla, prunes and some ashy hints that were quite unexpected (and not unpleasant). Turns lighter and more flowery after an hour in the glass, a tad sharp, at all times crisp and clear. It’s stern and uncompromising, a sharply cold winter’s day, precise and dry and singular.

P – Solid, sweetish and thick, very much into the fruity side of things – raisins, grapes, apples, fleshy stoned stuff, you know the ones. Also dates and some background brine, nicely done. A little dusty, dry, with aromatic tobacco notes, sour cream, cardboard, cereal and … what was this? … strawberries.

F – Quietly dry and a nice mix of musky and clear. Mostly cereals, cardboard, sawdust, together with apples, prunes, peaches and a sly flirt of vanilla, salty caramel and lemon zest.

T – Quite distinct and individualistic, one of the ECS that can perhaps be singled out blind.

Mark VIII — “Premise” 2008-2018 10 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-Sherry, Pot/Column Blend, 46%, 30,000 bottles

Mark VIII — “Premise” 2008-2018 10 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-Sherry, Pot/Column Blend, 46%, 30,000 bottles

N – If the Dominus was a clear winter’s day, then the Premise is a bright and warm spring morning, redolent of flowers and a basket of freshly picked fruit. Cumin, lime and massala, mixed up with apricot and green apples (somehow this works) plus grapes, olives and a nice brie. A bit salty with a touch of the sour bite of gooseberries, even pimentos (seriously!).

P – Very nice, quite warm and spicy, with a clear fruity backbone upon which are hung a smorgasbord of cooking spices like rosemary, dill and cumin. Faintly lemony and wine notes, merging well into vanilla, caramel and white nutty chocolate.

F – Delicately dry, with closing notes of caramel, vanilla, apricots and spices.

T – Too good to be labelled as mundane, yet there’s an aspect of “we’ve done this before” too. Not a rum you could pick out of a Foursquare lineup easily.

Summary

These tasting notes are just illustrative and for the purposes of this essay are not meant to express a clear preference of mine for one over any other (though I believe that some drop off is observable in the last couple of years). It is in aggregate that they shine, and the way they represent a higher quality than normal, issued over a period of many years. You hear lots of people praising the Real McCoy and Doorly’s lines of rums as the best of Barbados, but those are standard blends that remain the same for long periods. The Exceptionals are a different keg of wash entirely – each one is of large-but-limited release quantity, each is different, each shows Foursquare trying to go in yet another direction. Crowdsourced opinions rarely carry much weight with me, but when the greater drinking public and the social-media opinion-geeks and the reviewing community all have nothing but good to say about any rum, then you know you really have something that deserves closer scrutiny. And maybe it’s worth running over to the local store to buy one or more, just to see what the fuss is all about, or to confirm your own opinion of this series of Key Rums. Because they really are that interesting, that good, and that important.

Other Notes

- I am indebted to Jonathan Jacoby’s informative graphic of the Fousquare releases and their quantities which he posted up on Facebook when the question of how many bottles were issued to the market came up in September of 2018. It is the basis of the numbers quoted above. Big hat tip to the man for adding to the store of our knowledge here.

- In December 2020, the NW Rum Club did an 8-minute video summary of the high points of the 14-bottle range to that point (Detente). No tasting notes, just a quick series of highlights for the curious. Worth watching.

- Big thank you and deep appreciation also go out to Gregers, Henrik and Nicolai from Denmark, who, on 24 hours notice, managed to get me samples of the last three rums so I could flesh out the tasting notes section of this essay on the Marks VI, VII and VIII. You guys are the best.

- In late 2025 what appears to be the final two editions of the ECS were issued, called Mark XXX “Penultimus” and Mark XXXI “Epilogue”

The Complete ECS List, Updated January 2026

(Excludes Velier Collaborations, Habitation Velier and Private Cask Bottlings)

- Mark I – “1998” 1998-2008 10 YO, Bourbon Cask, 40%, 15,000 bottles

- Mark II – “Port Cask Finish” 2005-2014 9YO, 3yr-Bourbon, 6yr-Port, 40%, 30,000 bottles

- Mark III – “2004” 2004-2015 11 YO, Bourbon Cask, 59%, 24,000 bottles

- Mark IV – “Zinfadel” 2004-2015 11 YO Bourbon & Zinfadel casks, 43%, 24,000 bottles

- Mark V – “Criterion” 2007-2017 10 YO, 3yr-Bourbon, 7yr-Madeira, 56%, 4,000 bottles

- Mark VI – “2005” 2005-2017 12 YO, ex-bourbon, 59%, 24,000 bottles

- Mark VII – “Dominus” 2008-2018 10 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-cognac, 56%, 12,000 bottles

- Mark VIII – “Premise” 2008-2018 10 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-Sherry, 46%, 30,000 bottles

- Mark IX – “Empery” 2004-2018 14 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-Sherry, 56%, 12,000 bottles

- Mark X – “2007” 2007-2019 12 YO, ex-bourbon, 59%, 27,000 bottles

- Mark XI – “Sagacity” 2007-2019 12 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-Madeira, 48%, 24,000 bottles

- Mark XII – “Nobiliary” 2005-2019 14 YO, ex-bourbon, 62%, 12,000 bottles

- Mark XIII – “2008” 2008-2020 12 YO, ex-bourbon, 60%, 27,000 bottles

- Mark XIV – “Détente” 2010-2020 10 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-Port, 51%, 21,000 bottles

- Mark XV – “Redoubtable” 2006-2020 14 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-Madeira, 61%, 12,000 bottles

- Mark XVI – “Shibboleth” 2005-2021 16 YO, ex-bourbon, 56%, 9,600 bottles

- Mark XVII – “2009” 2009-2021 12 YO, ex-bourbon, 60%, 30,000 bottles

- Mark XVIII – “Indelible” 2010-2021 11 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-Zinfadel 46%

- Mark XIX – “Sovereignty” 2007-2021 14 YO, ex-bourbon, ex-Sherry, 62%, 12,000 bottles

- Mark XX – “Isonomy” 2005-2022 17 YO ex-bourbon, 58%, 8,400 bottles

- Mark XXI – “2010” 2010-2022 12 YO ex-bourbon, 60%, ~30,000 bottles

- Mark XXII – “Touchstone” 2008-2022 14 YO ex-bourbon, ex-cognac, 61%, xxxx bottles

- Mark XXIII – “Covenant” 2005-2023 18 YO ex-bourbon, 58%, xxxx bottles

- Mark XXIII – “Covenant”

- Mark XXIV – “2011”

- Mark XXV – “Equipoise”

- Mark XXVI – “Magisterium”

- Mark XXVII – “Equidem”

- Mark XXVIII – “Convocation”

- Mark XXIX – “Mandamus”

- Mark XXX – “Penultimus”

- Mark XXXI – “Epilogue”

In the last decade, several major divides have fissured the rum world in ways that would have seemed inconceivable in the early 2000s: these were and are cask strength (or full-proof) versus “standard proof” (40-43%); pure rums that are unadded-to versus those that have additives or are spiced up; tropical ageing against continental; blended rums versus single barrel expressions – and for the purpose of this review, the development and emergence of unmessed-with, unfiltered, unaged white rums, which in the French West Indies are called

In the last decade, several major divides have fissured the rum world in ways that would have seemed inconceivable in the early 2000s: these were and are cask strength (or full-proof) versus “standard proof” (40-43%); pure rums that are unadded-to versus those that have additives or are spiced up; tropical ageing against continental; blended rums versus single barrel expressions – and for the purpose of this review, the development and emergence of unmessed-with, unfiltered, unaged white rums, which in the French West Indies are called

So, given how many Jamaicans are on the scene these days, how does this young, continentally aged 55.9% golden rum fare? Not too shabbily. It’s strong but very approachable, even on the nose, which doesn’t waste any time getting started but announces its ester-rich aromas immediately and with authority: acetone, nail polish and some rubber plus a smell of righteous funk (spoiling fruits, rotten bananas, that kind of thing). Its relative youth is apparent in the uncouth sharpness of the initial aromas, but once one sticks with it, it settles into its own special groove, calms itself down and does a neat little balancing act between sharper scents of citrus, cider, apples, hard yellow mangoes and green grapes, and softer ones of bananas, cumin, vanilla, marshmallows and cloves.

So, given how many Jamaicans are on the scene these days, how does this young, continentally aged 55.9% golden rum fare? Not too shabbily. It’s strong but very approachable, even on the nose, which doesn’t waste any time getting started but announces its ester-rich aromas immediately and with authority: acetone, nail polish and some rubber plus a smell of righteous funk (spoiling fruits, rotten bananas, that kind of thing). Its relative youth is apparent in the uncouth sharpness of the initial aromas, but once one sticks with it, it settles into its own special groove, calms itself down and does a neat little balancing act between sharper scents of citrus, cider, apples, hard yellow mangoes and green grapes, and softer ones of bananas, cumin, vanilla, marshmallows and cloves.

Tasting revealed somewhat less clothing in the suitcase, though it was quite a decent rum to sip (mixing it is totally unnecessary) – it was a little sharp before settling down into a relative smooth experience, and tasted primarily of white and watery fruits (pears, watermelon, white gavas), cereals, coconut shavings, sweet wine, and had a sly hint of tart red fruiness that was almost, but not quite sour, behind it all – red currants, cranberries, grapes. It was quite light and easy and escaped being an alcohol-flavoured water in fine style – not bad for something at close to standard strength, and the touch of sweet fruitiness imparted by the Zin barrels was in no way overdone. Even the finish was quite pleasant, being warm, relatively soft, and closing off the show with some tart fruitiness, coconut shavings, vanilla, milk chocolate, salted caramel, french bread (!!) and touch of thyme.

Tasting revealed somewhat less clothing in the suitcase, though it was quite a decent rum to sip (mixing it is totally unnecessary) – it was a little sharp before settling down into a relative smooth experience, and tasted primarily of white and watery fruits (pears, watermelon, white gavas), cereals, coconut shavings, sweet wine, and had a sly hint of tart red fruiness that was almost, but not quite sour, behind it all – red currants, cranberries, grapes. It was quite light and easy and escaped being an alcohol-flavoured water in fine style – not bad for something at close to standard strength, and the touch of sweet fruitiness imparted by the Zin barrels was in no way overdone. Even the finish was quite pleasant, being warm, relatively soft, and closing off the show with some tart fruitiness, coconut shavings, vanilla, milk chocolate, salted caramel, french bread (!!) and touch of thyme.

Rumaniacs Review #84 | 0554

Rumaniacs Review #84 | 0554

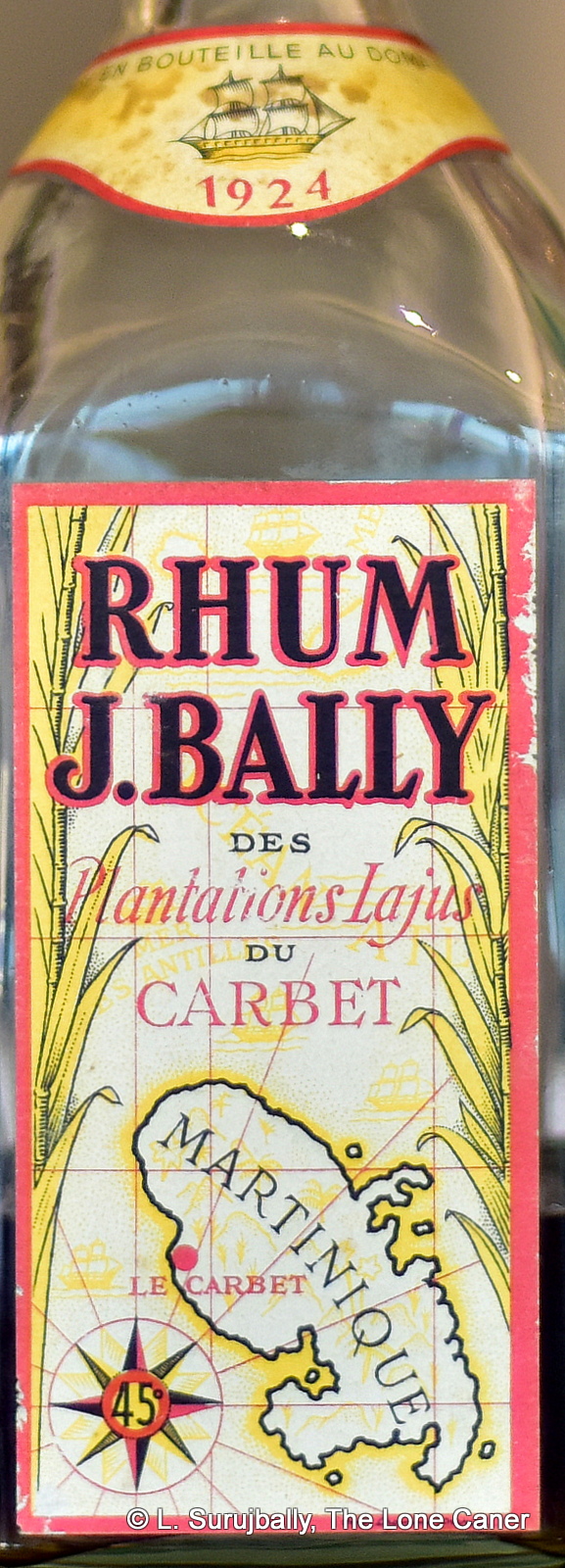

Aside from being made so long ago, what makes the 1924 special is that it was the initial release of an aged rhum from Bally, and one of the first of its kind in the French West Indies, if not

Aside from being made so long ago, what makes the 1924 special is that it was the initial release of an aged rhum from Bally, and one of the first of its kind in the French West Indies, if not

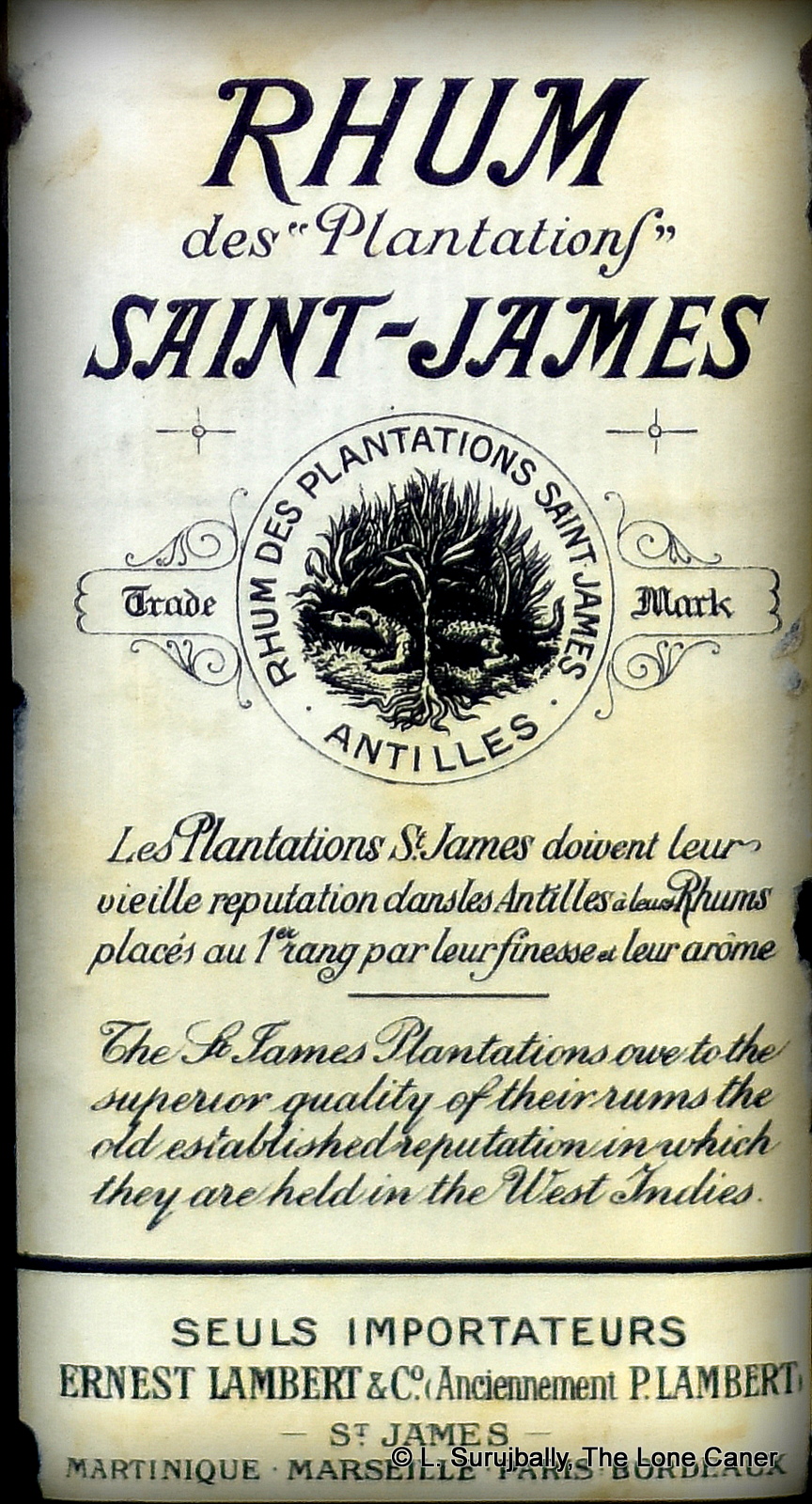

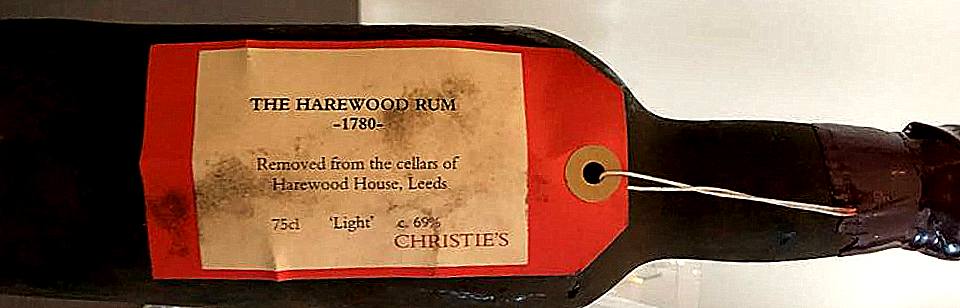

Still, we had to get facts, and a lot of our preliminary conversations and subsequent texts and messages revolved around the data points, which are as follows: the rhum was made in 1885 on Martinique, and derived from cane juice that was boiled prior to fermentation. Although the exact age is unknown, it was certainly shipped off the island before Mount Pelée erupted in 1902 and destroyed all stocks there, so at an absolute maximum it can be 17 years old. This is, however unlikely – few rums or rhums were aged that long back then, and the opinion of the master blender of St James (Mark Sassier) that it was 8-10 years old is probably the best one (

Still, we had to get facts, and a lot of our preliminary conversations and subsequent texts and messages revolved around the data points, which are as follows: the rhum was made in 1885 on Martinique, and derived from cane juice that was boiled prior to fermentation. Although the exact age is unknown, it was certainly shipped off the island before Mount Pelée erupted in 1902 and destroyed all stocks there, so at an absolute maximum it can be 17 years old. This is, however unlikely – few rums or rhums were aged that long back then, and the opinion of the master blender of St James (Mark Sassier) that it was 8-10 years old is probably the best one (

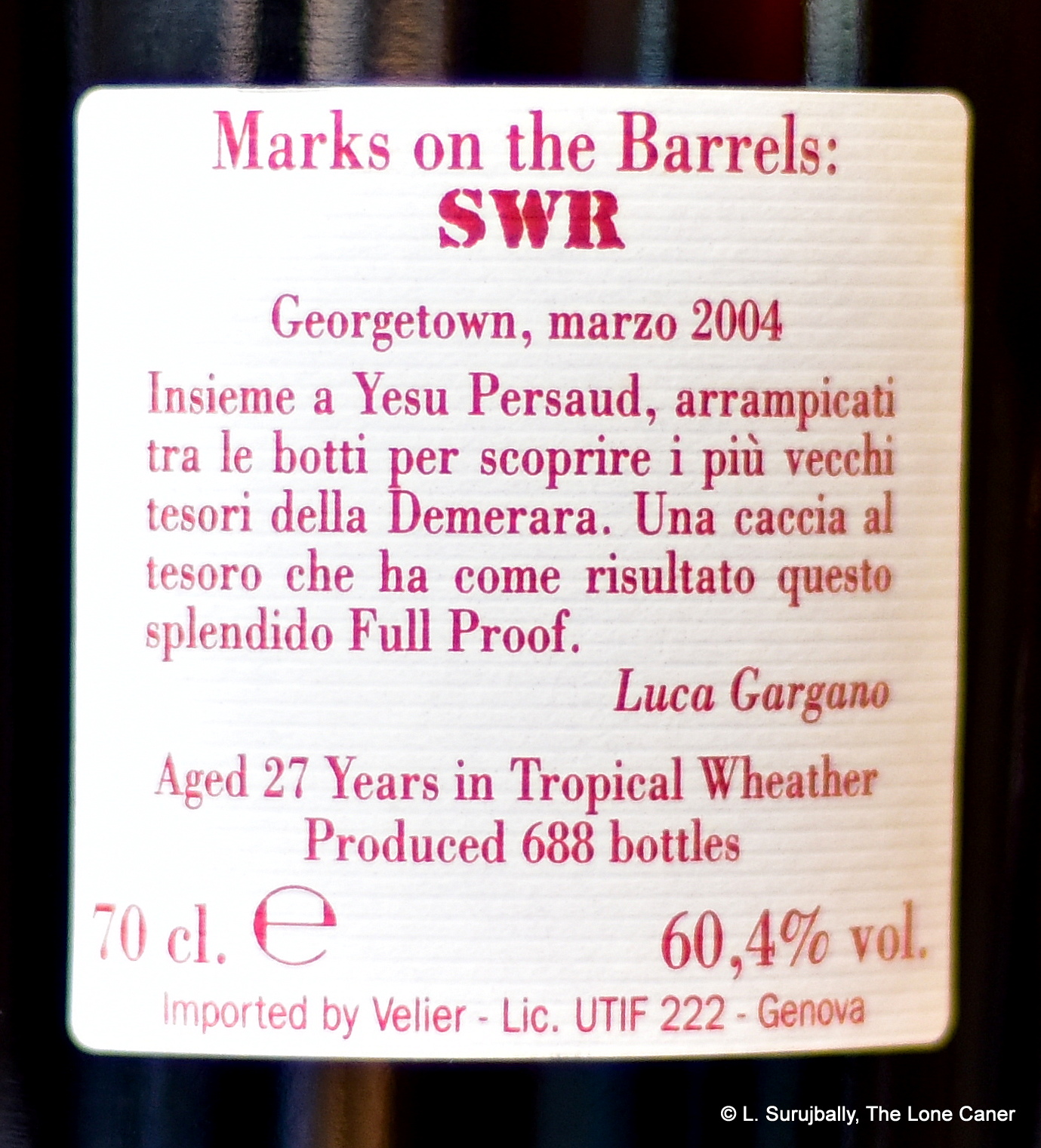

The history of the Skeldon 1978 bottling from a long-dismantled Savalle still is an odd one: the plantation is on the far eastern side of Guyana and the distillery has been shut down since 1960, though the original sugar factory’s remains continue to moulder away there, now replaced by a modern white elephant. It’s possible that the Savalle still which made it was taken elsewhere (Uitvlugt is the unconfirmed suspect) and this distillate hails from there rather than Skeldon — but certainly the “SWR” barrels ended up at Diamond, where Luca saw them gathering dust in the warehouse and convinced Yesu Persaud (the chairman of DDL at the time) to part with them. The 4-barrel 544-bottle outturn of the

The history of the Skeldon 1978 bottling from a long-dismantled Savalle still is an odd one: the plantation is on the far eastern side of Guyana and the distillery has been shut down since 1960, though the original sugar factory’s remains continue to moulder away there, now replaced by a modern white elephant. It’s possible that the Savalle still which made it was taken elsewhere (Uitvlugt is the unconfirmed suspect) and this distillate hails from there rather than Skeldon — but certainly the “SWR” barrels ended up at Diamond, where Luca saw them gathering dust in the warehouse and convinced Yesu Persaud (the chairman of DDL at the time) to part with them. The 4-barrel 544-bottle outturn of the  Although things at the Tasting were going faster than I was able to write (and listen), this was not a rum I wanted to be hurried with after waiting so long, and certainly it’s one with which to take one’s time. It unfolded gradually on the tongue, almost languorously and even at 60.4%, it was amazing how entirely under control it remained the entire time. Most of the tastes in the nose carried over, primarily anise, coffee and bitter chocolate, oranges, strong black tea, cumin, and that lentil soup / beef broth meatiness I remarked on earlier. But there were also more muted, subtler hints of papaya and fleshy fruits, aromatic tobacco, flambeed bananas and salty caramel. A rather dry note of over-roasted nuts came into play at the back end, a slight indeterminate bitterness (something like a manager who can never compliment your work without a closing criticism), but fortunately the muskier fruit and creamy notes ameliorated it for the most part. And while the finish was more a last bow on the stage than a true epilogue that added a few extra fillips of flavour, it was in no way disappointing, leaving me with a memory of coffee, nougat, salt caramel ice cream, fruits, raisins, licorice and light chocolate oranges.

Although things at the Tasting were going faster than I was able to write (and listen), this was not a rum I wanted to be hurried with after waiting so long, and certainly it’s one with which to take one’s time. It unfolded gradually on the tongue, almost languorously and even at 60.4%, it was amazing how entirely under control it remained the entire time. Most of the tastes in the nose carried over, primarily anise, coffee and bitter chocolate, oranges, strong black tea, cumin, and that lentil soup / beef broth meatiness I remarked on earlier. But there were also more muted, subtler hints of papaya and fleshy fruits, aromatic tobacco, flambeed bananas and salty caramel. A rather dry note of over-roasted nuts came into play at the back end, a slight indeterminate bitterness (something like a manager who can never compliment your work without a closing criticism), but fortunately the muskier fruit and creamy notes ameliorated it for the most part. And while the finish was more a last bow on the stage than a true epilogue that added a few extra fillips of flavour, it was in no way disappointing, leaving me with a memory of coffee, nougat, salt caramel ice cream, fruits, raisins, licorice and light chocolate oranges.

Well, that out of the way, let me walk you through the profile. Nose first: what was immediately evident is that it adhered to all the markers of a crisp agricole. It gave off of light grassy notes, apples gone off the slightest bit, watermelon, very light citrus and flowers. Then it sat back for some minutes, before surging forward with more: olives in brine, watermelon juice, sugar cane sap, peaches, tobacco and a sly hint of herbs like dill and cardamom.

Well, that out of the way, let me walk you through the profile. Nose first: what was immediately evident is that it adhered to all the markers of a crisp agricole. It gave off of light grassy notes, apples gone off the slightest bit, watermelon, very light citrus and flowers. Then it sat back for some minutes, before surging forward with more: olives in brine, watermelon juice, sugar cane sap, peaches, tobacco and a sly hint of herbs like dill and cardamom.

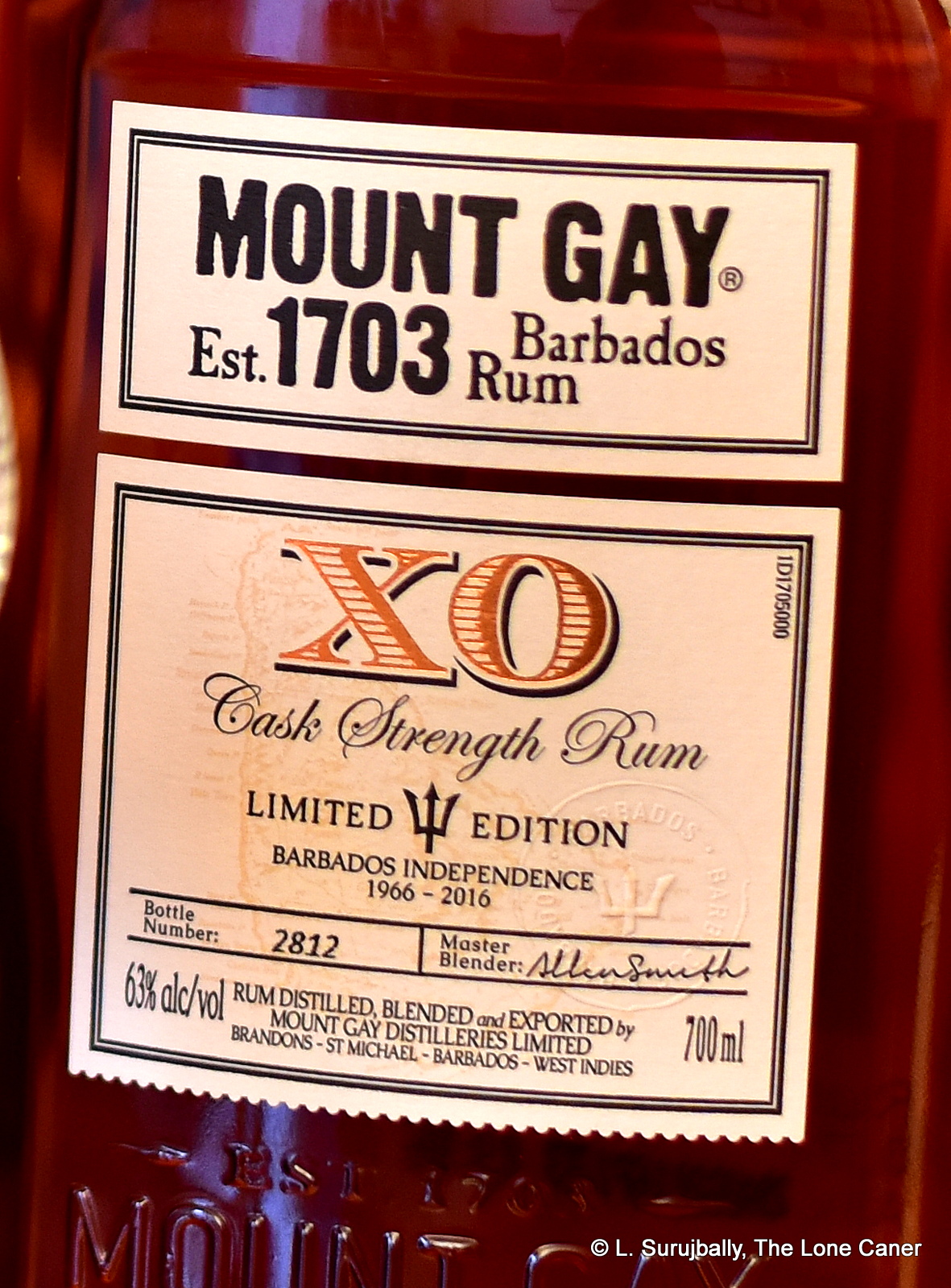

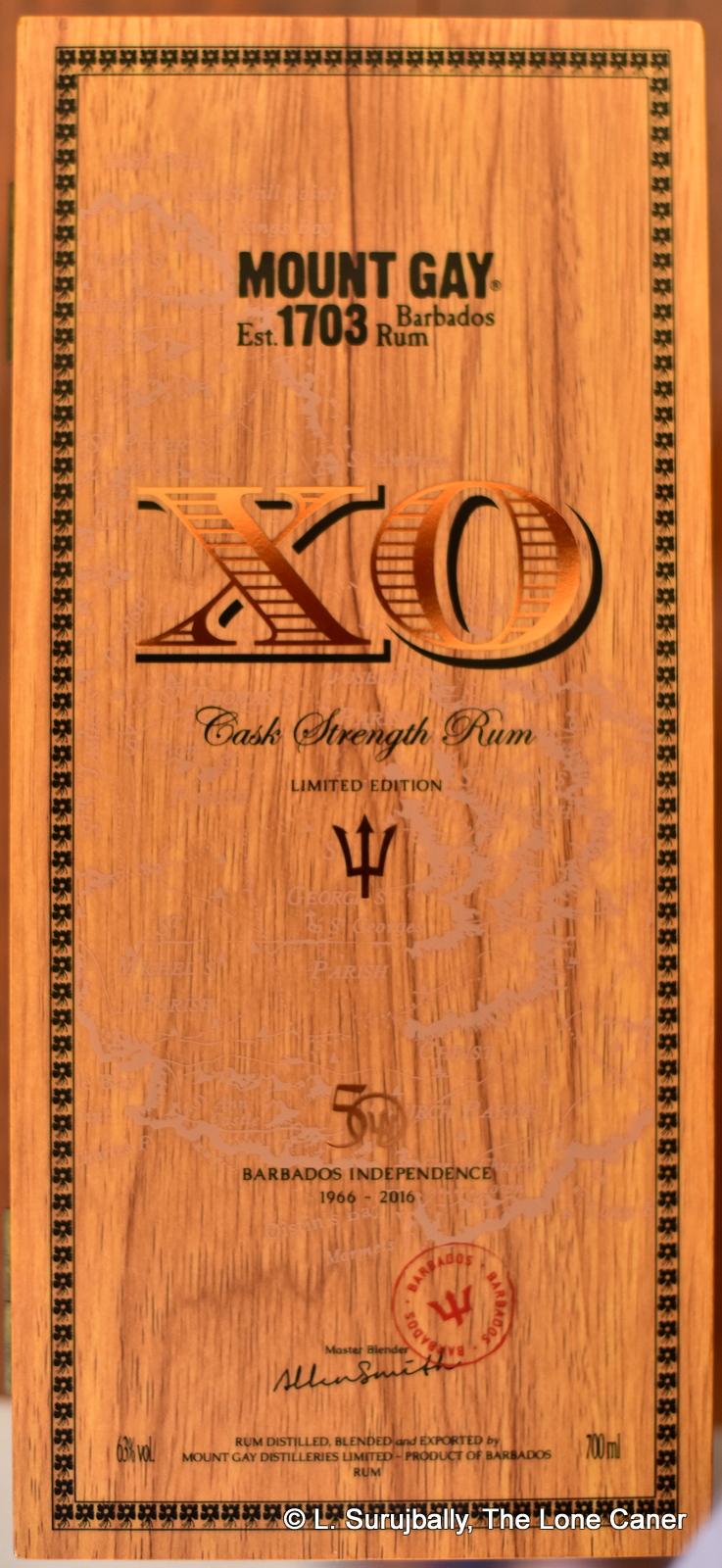

You can’t fault the presentation or the stats (though you might balk at the price). The ovoid bottle is nicely labelled with the bottle number and Allen Smith’s signature, comes in a handsome wooden box with a small booklet in it that speaks to the rum. It doesn’t state the outturn on the label, but it’s 3000 bottles, a rum to mark fifty years of independence though itself it is not that old, being a blend of pot and column still rums aged between 8-15 years old (just like the regular XO, even if one gets the impression that certain select barrels were chosen here). And of course the main selling point, the 63% ABV, Mount Gay’s first serious foray into these strong and dangerous rum currents.

You can’t fault the presentation or the stats (though you might balk at the price). The ovoid bottle is nicely labelled with the bottle number and Allen Smith’s signature, comes in a handsome wooden box with a small booklet in it that speaks to the rum. It doesn’t state the outturn on the label, but it’s 3000 bottles, a rum to mark fifty years of independence though itself it is not that old, being a blend of pot and column still rums aged between 8-15 years old (just like the regular XO, even if one gets the impression that certain select barrels were chosen here). And of course the main selling point, the 63% ABV, Mount Gay’s first serious foray into these strong and dangerous rum currents.

Rumaniacs Review #083 | 0544

Rumaniacs Review #083 | 0544 Opinion

Opinion

The bare statistics are brief and as follows: column still product, continentally aged; distilled 2004 and released in 2016 at a brobdingnagian 66.2% (its lesser proofed twin which is quite similar is bottled at 46% and 228 bottles were issued but about the full proof edition here, I’m not certain – less, for sure, maybe a hundred or so). Pale yellow in colour and a massive codpiece of a nose, deep and intense, which should not present as a surprise at all. It was quite aromatic as well – one could sense bananas, vanilla, prunes and fruit, with a nice counterpoint of citrus to set these off. Like many rums released at cask strength, it rewarded patience because after a while back-end smells of cream cheese, dark bread, brine, olives, nail polish, plastic bubble wrap (freshly popped), paint became much more evident, though fortunately without taking over entirely

The bare statistics are brief and as follows: column still product, continentally aged; distilled 2004 and released in 2016 at a brobdingnagian 66.2% (its lesser proofed twin which is quite similar is bottled at 46% and 228 bottles were issued but about the full proof edition here, I’m not certain – less, for sure, maybe a hundred or so). Pale yellow in colour and a massive codpiece of a nose, deep and intense, which should not present as a surprise at all. It was quite aromatic as well – one could sense bananas, vanilla, prunes and fruit, with a nice counterpoint of citrus to set these off. Like many rums released at cask strength, it rewarded patience because after a while back-end smells of cream cheese, dark bread, brine, olives, nail polish, plastic bubble wrap (freshly popped), paint became much more evident, though fortunately without taking over entirely

It was obvious after one tiny sniff, that not one percentage point of all that proofage was wasted and it was all hanging out there: approaching with caution was therefore recommended. I felt like I was inhaling a genetically enhanced rum worked over by a team of uber-geek scientists working in a buried government lab somewhere, who had evidently seen King Kong one too many times. I mean, okay, it wasn’t on par with the

It was obvious after one tiny sniff, that not one percentage point of all that proofage was wasted and it was all hanging out there: approaching with caution was therefore recommended. I felt like I was inhaling a genetically enhanced rum worked over by a team of uber-geek scientists working in a buried government lab somewhere, who had evidently seen King Kong one too many times. I mean, okay, it wasn’t on par with the