Photo (c) Excellence Rhum

Few profiles in the rum world are as distinctive Port Mourant, deriving from DDL’s double wooden pot still in Guyana. Now, the Versailles single wooden pot still rums always struck me as bit ragged and fierce, requiring rare skill to bring to their full potential, while the Enmores are occasionally too subtle: but somehow the PM tends to find the sweet spot between them and is almost always a good dram, whether continentally or tropically aged. I’ve consistently scored PM rums well, which may say more about me than the rum, but never mind.

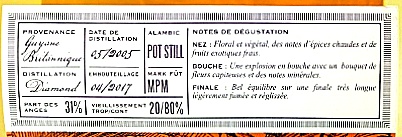

Here we have another independent bottling from that still – it comes from the Excellence Collection put out by the French store Excellence Rhum (where I’ve dropped a fair bit of coin over the years). Which in turn is run by Alexandre Beudet, who started the physical store and its associated online site in 2013 and now lists close on two thousand rums of all kinds. Since many stores like to show off their chops by issuing a limited “store edition” of their own, it’s not an illogical or uncommon step for them to take.

It’s definitely appreciated that it was released at a formidable 60.1% – as I’ve noted before, such high proof points in rums are not some fiendish plot meant to tie your glottis up in a pretzel (which is what I’ve always suspected about 151s), but a way to showcase an intense and powerful taste profile, to the max.

Certainly on the nose, that worked: hot and dry as the Sahara, it presented all the initial attributes of a pot still rum – paint, fingernail polish, rubber, acetones and rotten bananas to start, reminding me quite a bit of the Velier PM White and a lot fiercer than a gentler ultra-old rum like, oh the Norse Cask 1975. Once it relaxed I smelled brine, gherkins, sauerkraut, sweet and sour sauce, soya, vegetable soup, some compost and a lot of licorice, vanilla; and lastly, fruits that feel like they were left too long in the open sun close by Stabroek market. Florals and spices, though these remain very much in the background. Whatever the case, “rich” would not be a word out of place to describe it.

If the aromas were rich, so was the palate: more sweet than salt, literally bursting with additional flavours – of anise, caramel, vanilla, tons of dark fruits (and some sharper, greener ones like apples). There was also a peculiar – but far from unpleasant – hint of sawdust, cardboard, and the mustiness of dry abandoned rooms in a house too large to live in. But when all is said and done, it was the florals, licorice and darker fruits that held the heights, and this continued right down to the finish, which was long and aromatic, redolent of port-infused cigarillos, more licorice, creaminess, with a touch of rubber, acetones…and of course more fruits.

While PM rums do reasonably well with me because that’s the way my tastes bend, a caveat is that I also taste a whole lot of them, and that implies a PM rum had better be damned good to excite my serious interest and earn some undiluted fanboy favour and fervor….and a truly exemplary score. I started into the rum with a certain indulgent, “Yeah, let’s see what we have this time” attitude, and then stuck around to appreciate what had been accomplished. This is not the best of all Port Mourants, and I think a couple of drops of water might be useful, but the fact is that any rum of its family tree which I have on the go for a few hours and several glasses, is by no means a failure. It provides all the tastes which showcase the country, the still and the bottler, and proves once again that even with all of the many variations we’ve tried, there’s still room for another one.

(#599)(87/100)

Other Notes

- Major points for the back label design, which provides all the info we seek, but forgot to mention how many bottles we get to buy (thanks go to Fabien who pointed me in his comment below, to a link that showed 247 bottles).

- Distilled May 2005, bottled April 2017.

- Angel’s share 31%

- 20% Tropical, 80% Continental Ageing

Rumaniacs Review #091 | 0598

Rumaniacs Review #091 | 0598

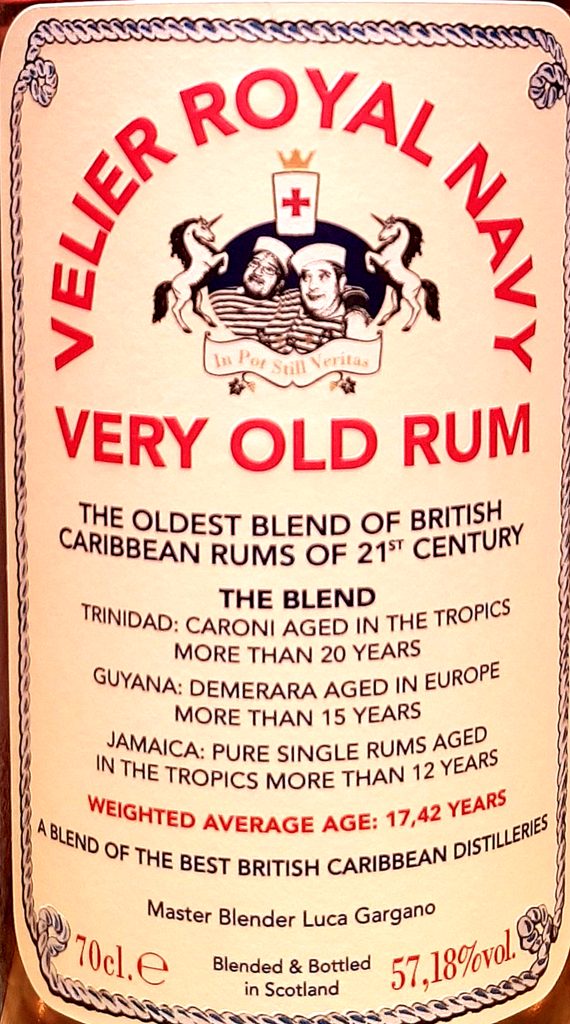

The nose suggested that this wasn’t far off. Mild for the strength, warm and aromatic, the first notes were deep petrol-infused salt caramel ice cream (yeah, I know how that sounds). Combining with that were some rotten fruit aromas (mangoes and bananas going off), brine and olives that carried the flag for the Jamaicans, with sharp bitter woody hints lurking around; and, after a while, fainter wooden and licorice notes from the Mudlanders (I’d suggest Port Mourant but could be the Versailles, not sure). I also detected brown sugar, molasses and a sort of light sherry smell coiling around the entire thing, together with smoke, leather, wood, honey and some cream tarts. Quite honestly, there was so much going on here that it took the better part of an hour to get through it all. It may be a navy grog, but definitely is a sipper’s delight from the sheer olfactory badassery.

The nose suggested that this wasn’t far off. Mild for the strength, warm and aromatic, the first notes were deep petrol-infused salt caramel ice cream (yeah, I know how that sounds). Combining with that were some rotten fruit aromas (mangoes and bananas going off), brine and olives that carried the flag for the Jamaicans, with sharp bitter woody hints lurking around; and, after a while, fainter wooden and licorice notes from the Mudlanders (I’d suggest Port Mourant but could be the Versailles, not sure). I also detected brown sugar, molasses and a sort of light sherry smell coiling around the entire thing, together with smoke, leather, wood, honey and some cream tarts. Quite honestly, there was so much going on here that it took the better part of an hour to get through it all. It may be a navy grog, but definitely is a sipper’s delight from the sheer olfactory badassery.

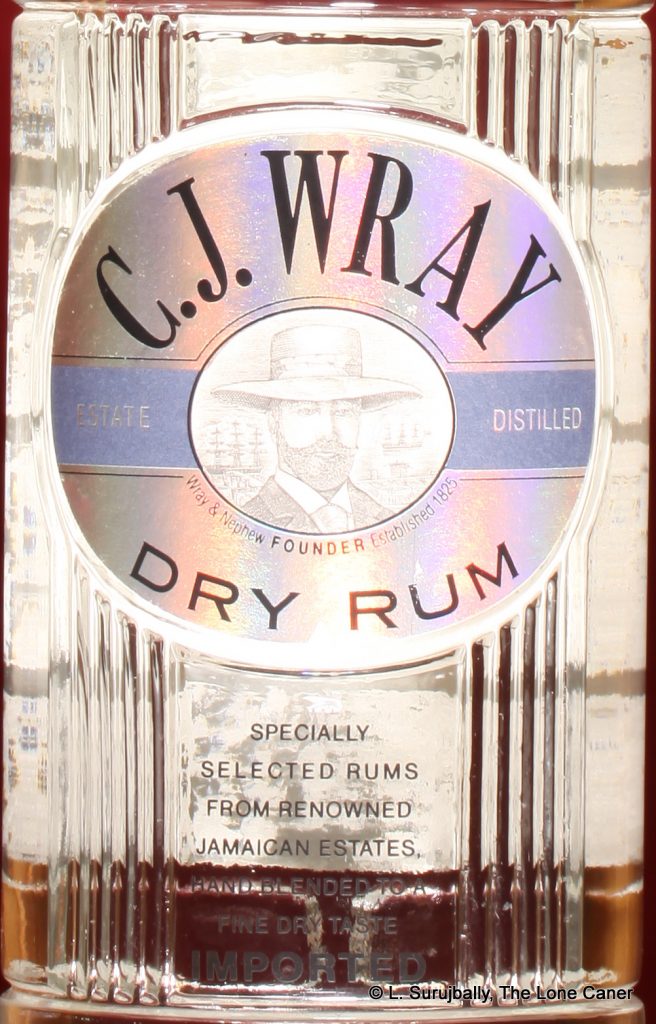

Technical details are murky. All right, they’re practically non-existent. I think it’s a filtered column still rum, diluted down to standard strength, but lack definitive proof – that’s just my experience and taste buds talking, so if you know better, drop a line. No notes on ageing – however, in spite of one reference I dug up which noted it as unaged, I think it probably was, just a bit.

Technical details are murky. All right, they’re practically non-existent. I think it’s a filtered column still rum, diluted down to standard strength, but lack definitive proof – that’s just my experience and taste buds talking, so if you know better, drop a line. No notes on ageing – however, in spite of one reference I dug up which noted it as unaged, I think it probably was, just a bit.

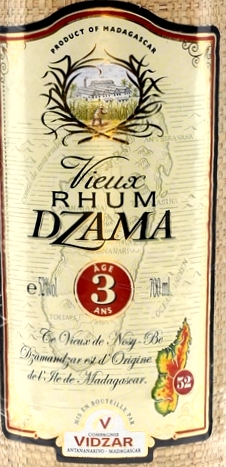

All that said, there isn’t much on the company website about the technical details regarding the 3 year old we’re looking at today. It’s a column still rum, unadded-to, aged in oak barrels, and my sample clocked in at 52%, which I think is an amazing strength for a rum so young – most producers tend to stick with the tried-and-true 40-43% (for tax and export purposes) when starting out, but not these guys.

All that said, there isn’t much on the company website about the technical details regarding the 3 year old we’re looking at today. It’s a column still rum, unadded-to, aged in oak barrels, and my sample clocked in at 52%, which I think is an amazing strength for a rum so young – most producers tend to stick with the tried-and-true 40-43% (for tax and export purposes) when starting out, but not these guys.

That’s not to say that in this case the

That’s not to say that in this case the

The Jack Iron rum from Westerhall is a booming overproof issued both in a slightly aged and a white version, and both are a whopping 70% ABV. While you can get it abroad — this bottle was tried in Italy, for example — my take is that it’s primarily a rum for local consumption (though which island can lay claim to it is a matter of idle conjecture), issued to paralyze brave-but-foolhardy tourists who want to show off their Chewbacca chests by drinking it neat, or to comfort the locals who don’t have time to waste getting hammered and just want to do it quick time. Add to that the West Indian slang for manly parts occasionally being iron and you can sense a sort of cheerful and salty islander sense of humour at work (see “other notes” below for an alternative backstory).

The Jack Iron rum from Westerhall is a booming overproof issued both in a slightly aged and a white version, and both are a whopping 70% ABV. While you can get it abroad — this bottle was tried in Italy, for example — my take is that it’s primarily a rum for local consumption (though which island can lay claim to it is a matter of idle conjecture), issued to paralyze brave-but-foolhardy tourists who want to show off their Chewbacca chests by drinking it neat, or to comfort the locals who don’t have time to waste getting hammered and just want to do it quick time. Add to that the West Indian slang for manly parts occasionally being iron and you can sense a sort of cheerful and salty islander sense of humour at work (see “other notes” below for an alternative backstory).

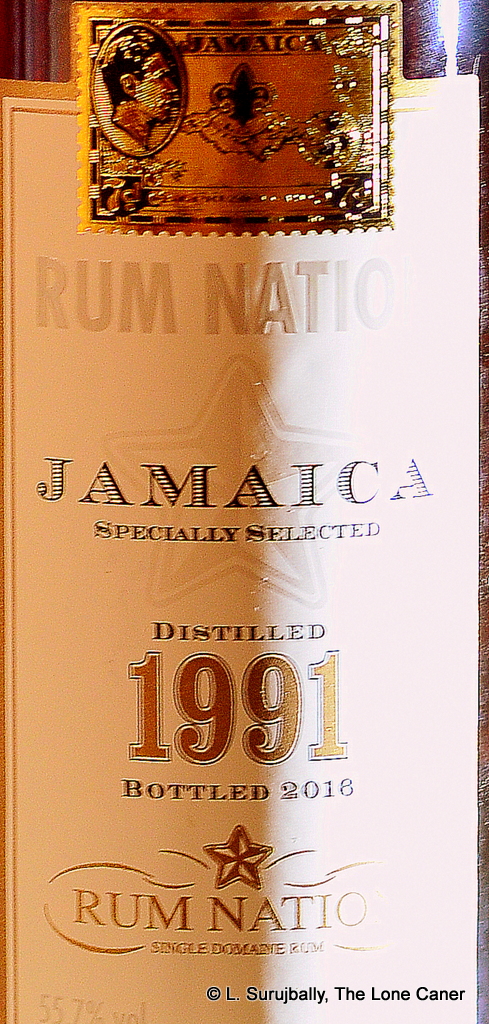

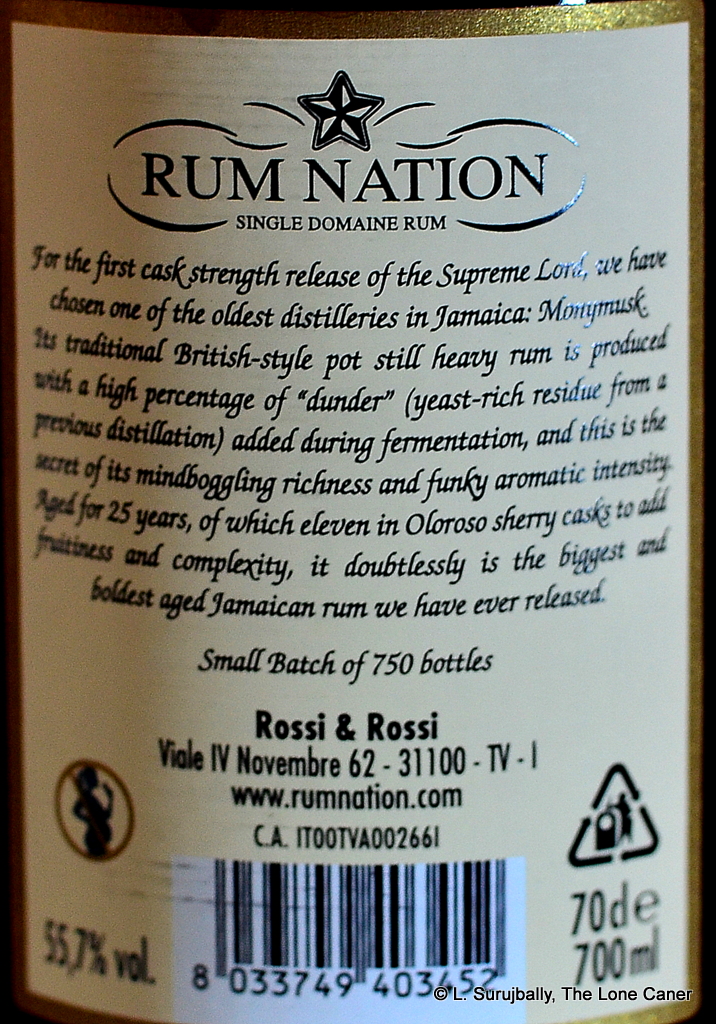

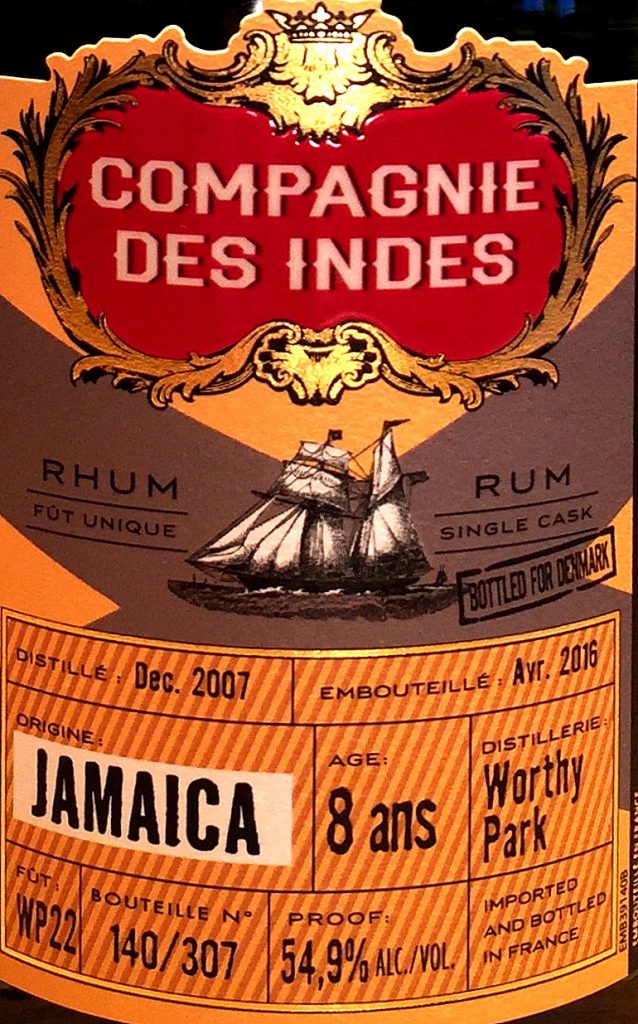

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the  The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

This brings us to the

This brings us to the

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything.

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything. Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

We don’t much associate the USA with cask strength rums, though of course they do exist, and the country has a long history with the spirit. These days, even allowing for a swelling wave of rum appreciation here and there, the US rum market seems to be primarily made up of low-end mass-market hooch from massive conglomerates at one end, and micro-distilleries of wildly varying output quality at the other. It’s the micros which interest me, because the US doesn’t do “independent bottlers” as such – they do this, and that makes things interesting, since one never knows what new and amazing juice may be lurking just around the corner, made with whatever bathtub-and-shower-nozzle-held-together-with-duct-tape distillery apparatus they’ve slapped together.

We don’t much associate the USA with cask strength rums, though of course they do exist, and the country has a long history with the spirit. These days, even allowing for a swelling wave of rum appreciation here and there, the US rum market seems to be primarily made up of low-end mass-market hooch from massive conglomerates at one end, and micro-distilleries of wildly varying output quality at the other. It’s the micros which interest me, because the US doesn’t do “independent bottlers” as such – they do this, and that makes things interesting, since one never knows what new and amazing juice may be lurking just around the corner, made with whatever bathtub-and-shower-nozzle-held-together-with-duct-tape distillery apparatus they’ve slapped together.