An essay in Oriental and Caribbean fusion

#326

Outside the cognoscenti, the rabid fanbase or deep-field researchers, few know (or care) much about rums from outside the Western hemisphere. Yet rums from India and Thailand and Australia are massive sellers in the East, to say nothing of the emergent makers from Japan. Nine Leaves is the newest outfit from the Land of the Rising Sun to garner major accolades in the larger rumiverse, but rum has been made from locally grown sugar for a very long time, and it’s no surprise that other companies have been quietly doing business in the spirit without many outside the region being the wiser. Whisky might be the Japanese attention-getter du jour, but I don’t review those, so let’s turn a small spotlight on to the rums instead.

One such is this very interesting pale yellow product from the Kikusui distillery, located in the Niigata Prefecture on the north coast of Honshu — they also make, and are mostly known for, sake. The Kikusui brewery was formed in 1881 by Takasawa Suguro, when he received the right to make it from his uncle Takasawa Masanori and was approved to make it in his own right in 1896. It remains a family business (into its fifth generation), with sake remaining the mainstay of the company (one can only wonder who the rum loving guy in the family was, who broke with tradition by making it). In the first century of its existence, the company was not a large one, and weathered many storms like shortage of rice, the war years, sickness and premature death of family members, floods, earthquakes – in 1964 the brewery was damaged by earthquake and for two consecutive years floods destroyed what was left. Somehow the family kept going and in 1969 a replacement brewery was completed. New equipment, modern production methods and management techniques were introduced in the 1970s. In the 1980s and 1990s the company branched out into canned sake, food dishes and even stores of its own. Sometime in the 2000s, as best as I can determine and perhaps as a result of western influences or lack of desire to go with whisky, it was decided to branch into rum.

The sugar cane from which it is made comes from the southern island of Shikoku, the smallest island in the chain, and the rum derives from freshly pressed cane, which would make it a Japanese agricole, as well as putting to the test my own theories about whether terroire really does have a major influence on the final product. There is no information on whether the rum is pot still or column still derived; it’s aged for seven years in American oak barrels, and issued at 40%. There you go.

It’s been a while since I tried a rum with an olfactory profile quite like this: it started out with a wet cardboard soggy mess (the cardboard that the aroma implied, that is, not the rum); and cereals, rye bread, coconut water, rotting fruit (it was gentle, for which I gave fervent thanks), which over time, developed into a very pleasant nose of apples and cider, oddly sharp and weak at the same time. It was very light, faintly sweet, and could not for a moment compare to the clear voluptuousness of a Caribbean agricole, yet it presented an intriguing profile of its own that was almost Jamaican, and marked it out as singular – clearly, one had to be prepared to take a sharp left turn to enjoy it and not demand it adhere to a better known French island smell. I can’t say with conviction that I succeeded…but I was intrigued.

The palate was just as interesting, if equally bizarre. To begin with, it was very different from the way it smelled – it was clear and crisp on the tongue as any cane-juice-derived rum ever made, extraordinarily light and clean for something supposedly aged for seven years, and tasted of light sweet grapes (those red ones from Turkey, or the green ones from Lebanon my wife buys for me), cucumbers, dill, and very light notes of vanilla, green apples, flowers, green tea ice cream, pears, some smoke, and a vague soya sauce background. In other words, the dreadlocks to a big step backwards. It was sprightly, light, crisp. Too bad the finish decided to circle back to the beginning, and end things with more of those fruits that had gone off, and that wet cardboard, tied in a bow with olives and brine. A little was okay, too much kinda soured on me.

So…I enjoyed the offbeat, original taste, liked the crispness of the mouthfeel, and was okay with the edges front and back, yet there was something uninspiring about the experience taken as a whole. It’s possible that both terroire and the company’s expertise with (or preference for) sake tilted their philosophy to something at odds with more familiar rummy profiles; and of course the 40% while allowing a wider audience to be catered to, does impose some limitations. Still, I’ll say this – it is emphatic for what it is, and as a rum it sure makes its own statement. There’s more than a bit of unaged pot still profile in here (hence my unconfirmed suspicion that this is what they are using to distil it), but for that to take a more commanding stance requires moving above the issued ABV and maybe playing with the barrel strategy some more. At end, therefore, it exhibits both strengths and weaknesses.

Why did I buy this? Well, because I could, because I was interested, and because it’s informative and useful to write about more than just the regular crop of rums from the regions with which we are all familiar. We should look to expand our horizons, and if the experience is not always an unadulterated positive, who can say what others might like, what the company’s ten year old is like, or where it moves in the future? Happily, the Ryoma 7 year old rum exhibited more on the plus side of the ledger than minuses, was a sprightly, funky little rumlet, and is quite affordable for anyone who wants to take a flier on something off the beaten track.

(80/100)

Other notes

The name “Ryoma” (or Ryōma) is that of one of the revolutionaries of the Meiji era who was prominent in the movement to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate (he was murdered in 1867). That name in turn derives from a legend of a god with the head of a dragon and the body of a horse, which supposedly could run 1000 li in one day.

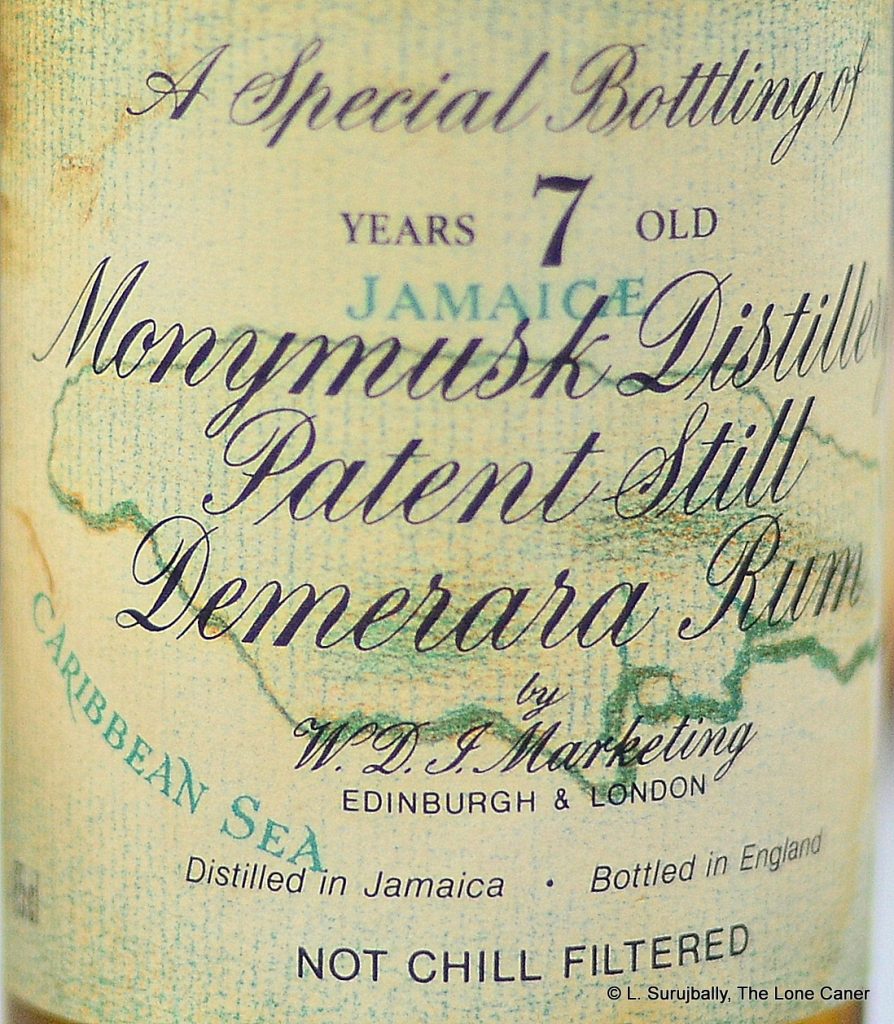

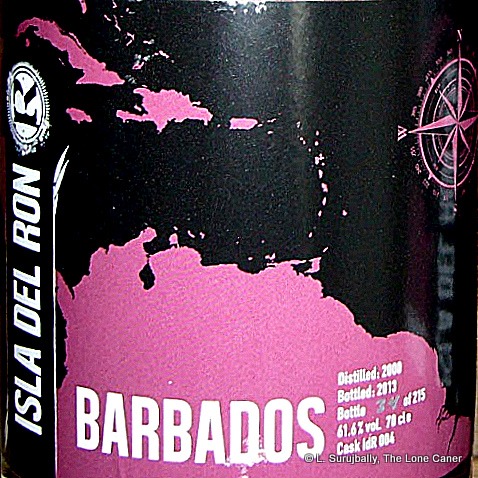

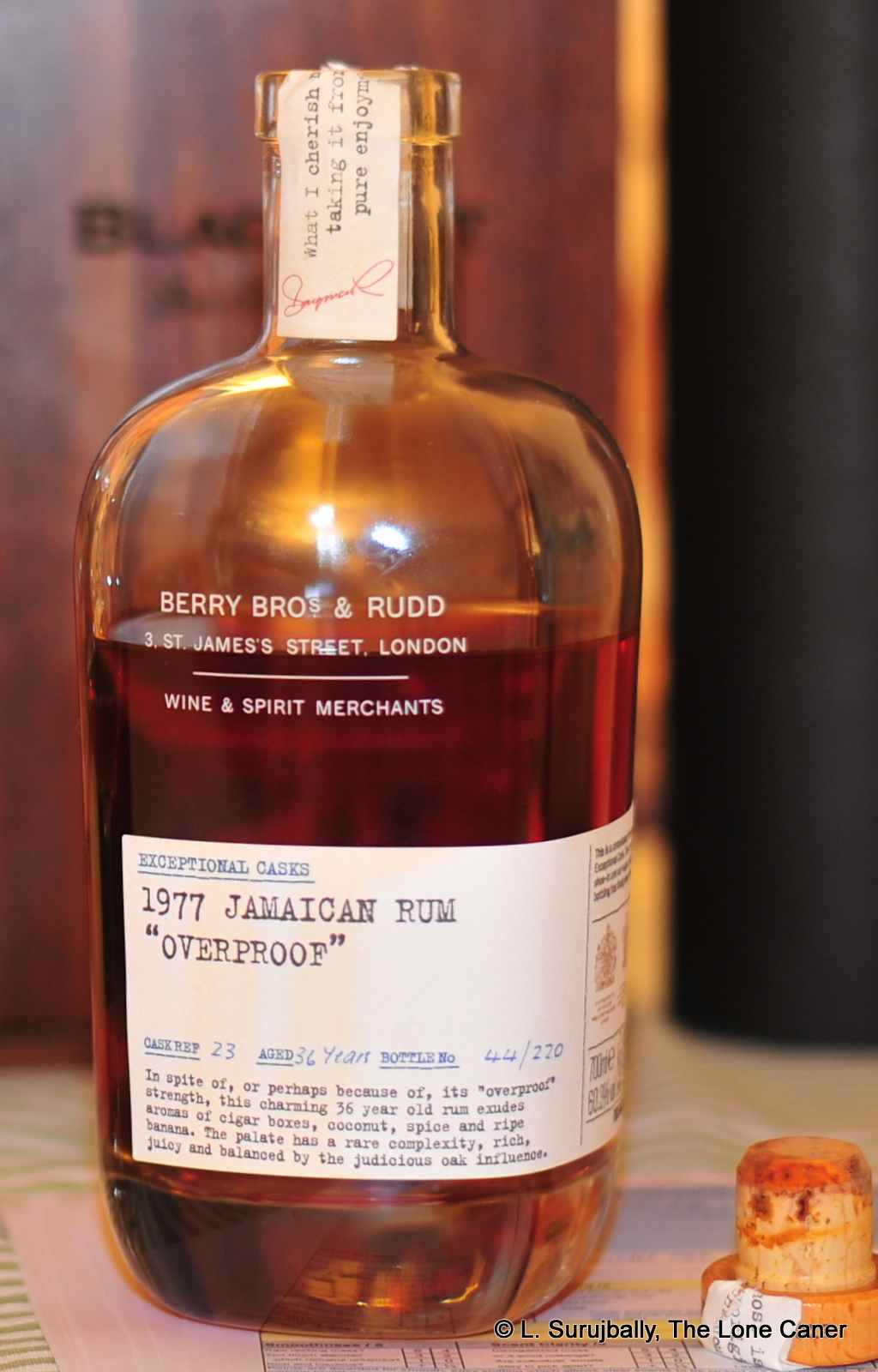

Nose – Yeah, no way this is from Mudland. The funk is all-encompassing. Overripe fruit, citrus, rotten oranges, some faint rubber, bananas that are blackened with age and ready to be thrown out. That’s what seven years gets you. Still, it’s not bad. Leave it and come back, and you’ll find additional scents of berries, pistachio ice cream and a faint hint of flowers.

Nose – Yeah, no way this is from Mudland. The funk is all-encompassing. Overripe fruit, citrus, rotten oranges, some faint rubber, bananas that are blackened with age and ready to be thrown out. That’s what seven years gets you. Still, it’s not bad. Leave it and come back, and you’ll find additional scents of berries, pistachio ice cream and a faint hint of flowers.

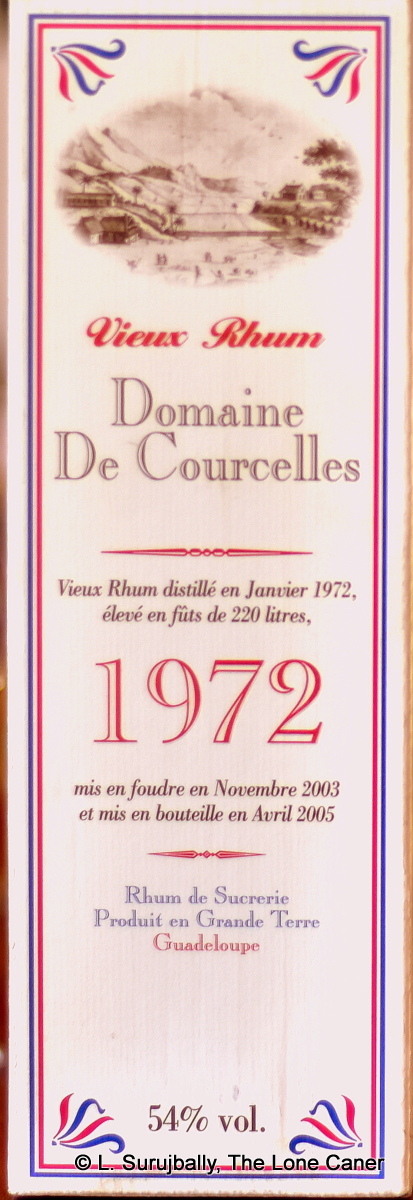

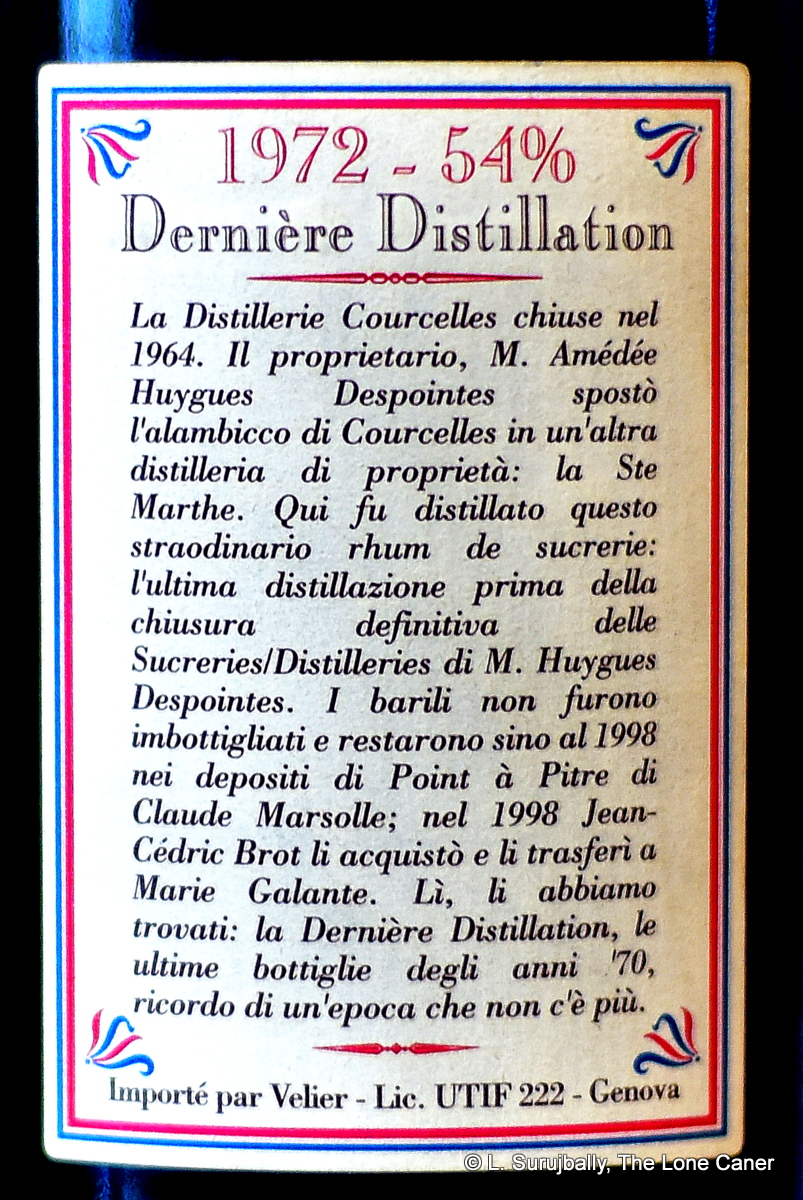

A well made full proof rum should be intense but not savage. The point of the elevated strength is not to hurt you, damage your insides, or give you an opportunity to prove how you rock it in the ‘Hood — but to provide crisper, clearer and stronger tastes that are more distinct (and delicious). When done right, such rums are excellent as both sippers or cocktail ingredients and therein lies much of their attraction for people across the drinking spectrum. Perhaps in the years to come, there’s the potential for rum makers to reach into the past and recreate such a remarkable profile once again. I can hope, I guess.

A well made full proof rum should be intense but not savage. The point of the elevated strength is not to hurt you, damage your insides, or give you an opportunity to prove how you rock it in the ‘Hood — but to provide crisper, clearer and stronger tastes that are more distinct (and delicious). When done right, such rums are excellent as both sippers or cocktail ingredients and therein lies much of their attraction for people across the drinking spectrum. Perhaps in the years to come, there’s the potential for rum makers to reach into the past and recreate such a remarkable profile once again. I can hope, I guess.