Given my despite and disdain for the overhyped, oversold and over-sugared spiced-alcoholic waters that were the Phillipine Don Papa 7YO and 10YO, you’d be within your rights to ask if I either had a screw loose or was a glutton for punishment, for going ahead and trying this one. Maybe both, I’d answer, but come on, gotta give each rum a break on its own merits, right? If we only write about stuff we like or know is good, then we’re not pushing the boundaries of discovery very much now, are we?

All this sounds nice, but part of the matter is more prosaic — I had the sample utterly blind. Didn’t know what it was. John Go, my cheerfully devious friend from the Phillipines sent me a bunch of unlabelled samples and simply said “Go taste ‘em,” without so much as informing me what any of them where (we indulge ourselves in such infantile pursuits from time to time). And so I tasted it, rated it, scored it, and was not entirely disappointed with it. It was not an over sugared mess, and it did not feel like it was spiced up to the rafters — though I could not test it, so you’ll have to take that into account when assessing whether these notes can be relied upon or not.

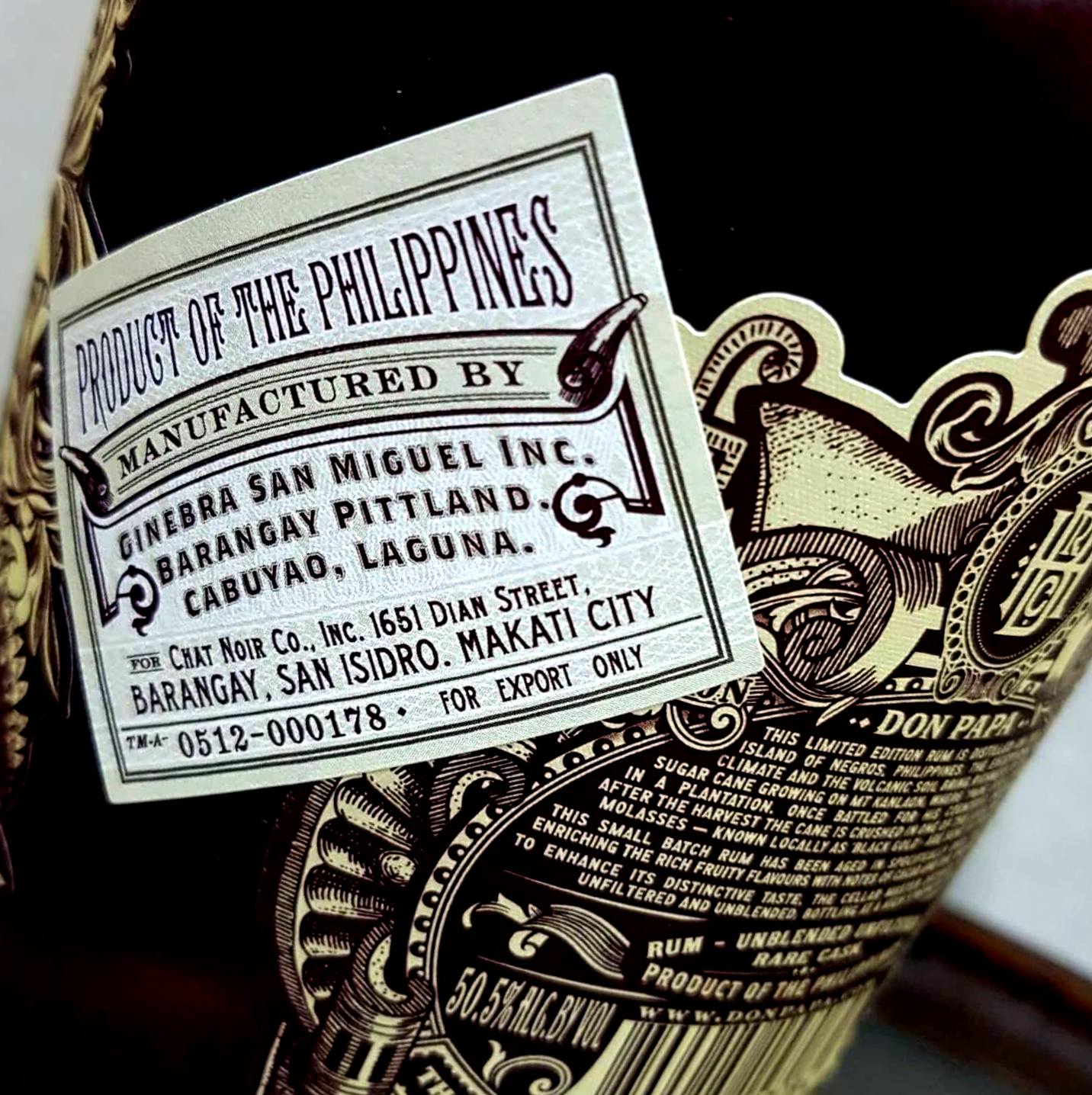

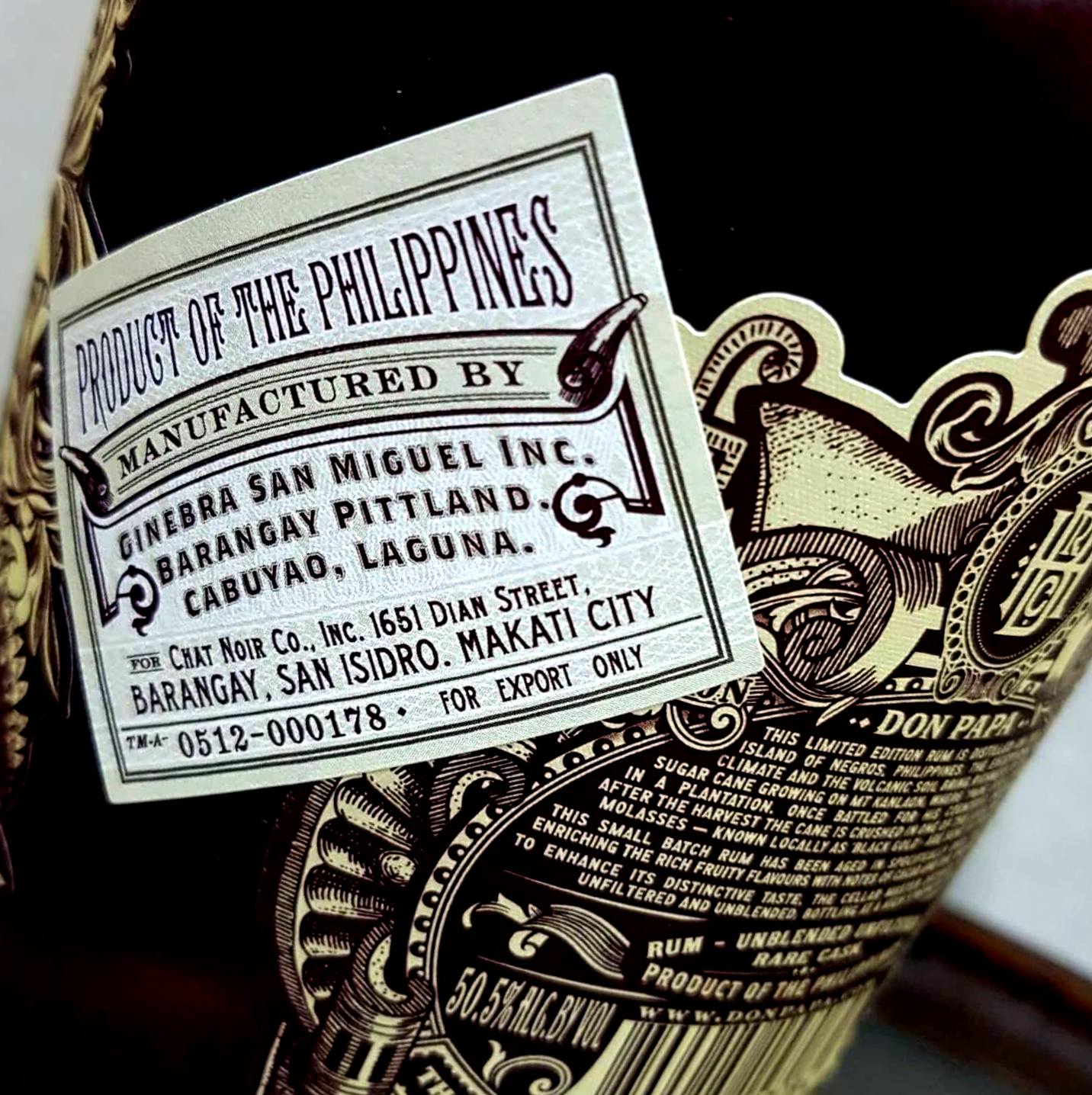

That said, let’s see what we are told officially. Bleeding Heart Rum company issued 6000 bottles of the Rare Cask in 2017 at 50.5% ABV – which is immediately proved to be a problem (dare I say “lie”?) because this is bottle #8693 – and just about all online stores and online spirits articles speak to how the rum has no filtration and no “assembly”…well, okay. One site (and the label) called it unblended, which of course is nonsense given the outturn. Almost all mention the “STR” – shaved, toasted and roasted – barrels used, which we can infer to mean charred. There’s no age statement to be found. And there’s no mention of additives of any kind, the stuff which so sullied the impressions of the 7 and 10 year old: and although I have been told it’s clean, that was something I was unable to test for myself and wouldn’t trust if it came from them (see opinion below). You can decide for yourself whether that kind of outturn and information provision qualifies the tag of “Rare Cask.” It doesn’t for me.

With all that behind us, what’s it like? Well, even with the amber colour, it noses very lightly…it’s almost relaxing (not really normal for 50% ABV). Somewhat sharp, not too much, smells of sweet tinned peaches in syrup, with spices like nutmeg and cinnamon being noticeable, plus floral notes, vague salt crackers, bitter chocolate, vanilla and oatmeal cookies. My notes speak of how delicate it noses, but at least the thick cloying blanket of an over-sweetened liqueur does not seem to be part of the program. In its own way it’s actually quite precise and not some vague mishmash of aromas that just flow together randomly.

The taste is different – here it reminds one of the El Dorado 12 (not the 15, that’s a reach) – with a strong toffee, vanilla, brown sugar and molasses backbone. Lots of fruitiness here – raisins and orange peel, more of those tinned peaches – and also ginger, cinnamon, and bitter chocolate together with strong black tea. These latter tastes balance off the muskiness of the molasses and vanilla, and even if it has been sugared up (and I suspect that if it has, it is less compared to the others in the line), that part seems to be more restrained, to the point where it doesn’t utterly detract or seriously annoy. The finish is surprisingly short for a rum at 50%, and sharper, mostly brown sugar, fruit syrup, caramel and chocolate, nothing new here.

So all in all, somewhat of a step up from the 7 and the 10. Additives are always a contentious subject, and I understand why some makers prefer to go down that road (while not condoning it) — what I want and advocate for is complete disclosure, which is (again) not the case with the Rare Cask. Here Bleeding Heart seem to have dispensed with the shovel and used a smaller spoon, which suggests they’re paying some attention to trends in the rum world. When somebody with a hydrometer gets around to testing this thing, I hope to know for certain whether it’s adulterated or not, but in the meantime I’m really glad I didn’t know what I was trying. That allowed me to be unbiased by the other two rums in the dustbin of my tasting memories when doing my evaluation, and I think this is a light-to-medium, mid-tier rum, probably five years old or less, not too complex, not too simple, with a dash of something foreign in there, but a reasonably good drink all round — especially when compared to its siblings.

(#537)(78/100)

Other Notes

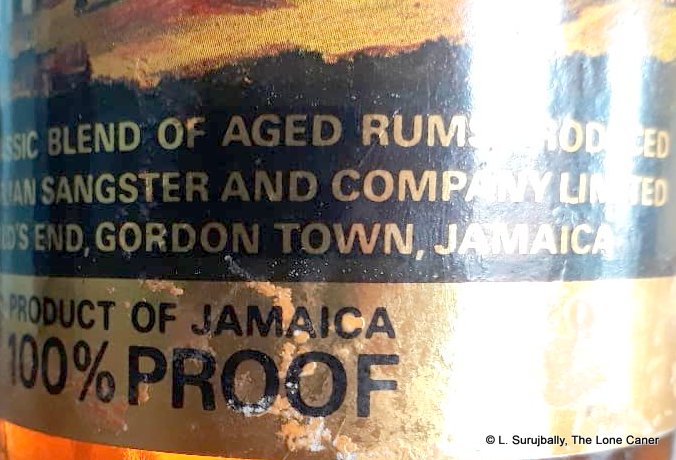

According to the bottle label, the distillery of origin is the Ginebra San Miguel, founded in 1834 when Casa Róxas founded the Ayala Distillery (the first in the Philippines). Known primarily for gin, it also produced other spirits like anisette, cognac, rum and whisky, some locally, some under license. The distillery was located in Quiapo, Manila and was a major component of Ayala y Compañia (successor of Casa Róxas), which was in turn acquired by La Tondeña in 1924.

La Tondeña, in turn, was established in 1902 by Carlos Palanca, Sr. in Tondo, Manila and incorporated as La Tondeña Inc. in 1929. Its main claim to fame prior to its expansion was the production of alcohol derived from molasses, instead of the commonly used nipa palm which it rapidly displaced. Bleeding Heart is associated with the company only insofar as they evidently buy rum stock from then, though at what stage in the production or ageing process, with what kind of still, and with what inclusions, is unknown.

Opinion

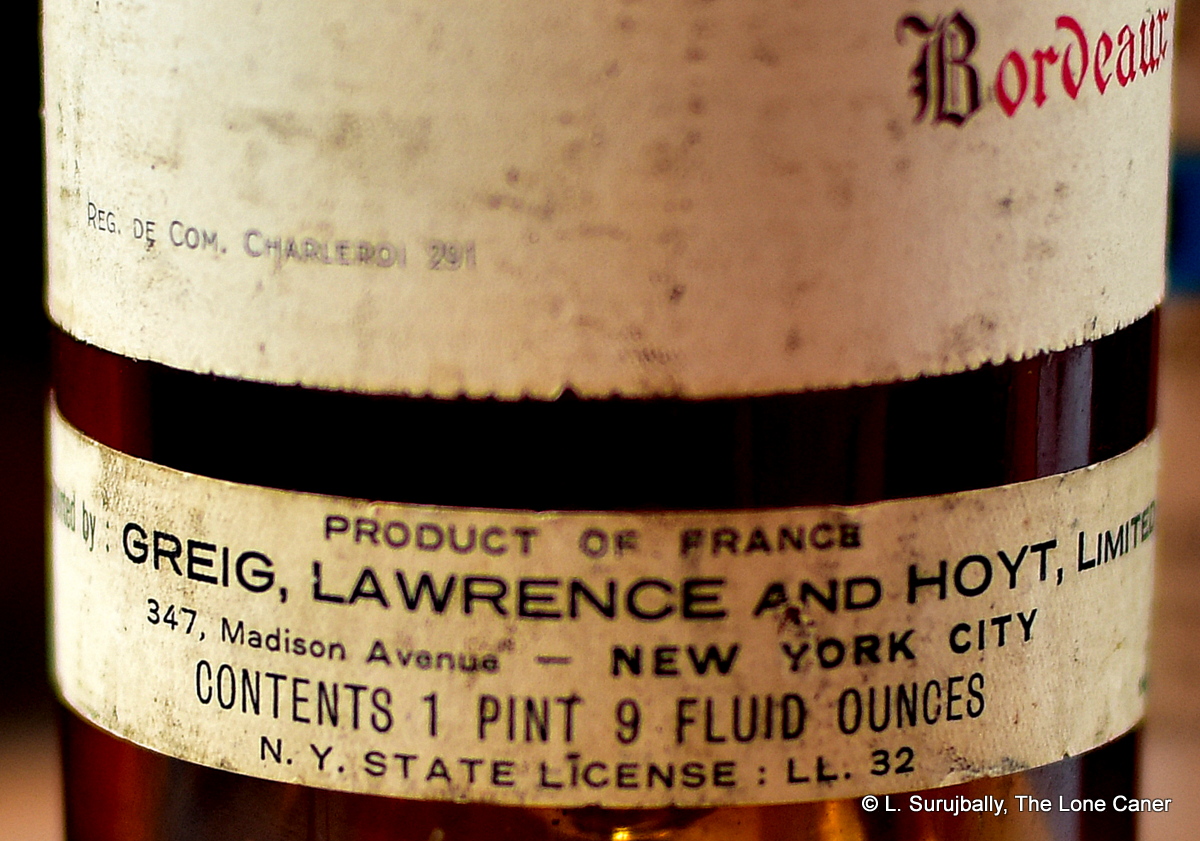

One of the key concepts coiling around the various debates about additives is the matter of trust. “I don’t trust [insert brand name here] further than I can throw ‘em,” is a constant refrain and it usually pops up when adulteration is noted, suspected, proved or inferred. But the underlying fact is that we do trust the producers. We trust them all the time, perhaps not with marketing copy, the hysterical advertising, the press releases, the glowing brand ambassadors’ endorsements, true – but with what’s on the bottle itself.

The information on the label may be the most sacred part of any rum’s background. Consciously or not, we take much of what it says as gospel: specifically the country of origin, the distillery source, the age, whether it is a blend or not, and the strength (against which all hydrometer tests are rated). Gradually more and more information is being added – tropical versus continental ageing, the barrel number, angel’s share, production notes, and so on.

We trust that, and when it’s clear there is deception and outright untruth going on (quite aside from carelessness or stupidity, which can happen as well), when that compact between producer and consumer is broken, it’s well-nigh impossible to get it back — as any amount of Panamanian rum brands, Flor de Cana (and their numbers) or Dictador “Best of…” series can attest (the Best of 1977, as well as the Malecon 79 and the Mombacho 19 reviews all had commentaries on trust, and for similar reasons). Also, for example, not all companies who claim their rums are soleras have been shown to really make them that way (often they are blends); and aside from spiced and flavoured rums (and Plantation) just about no producer admits to dosing or additives…so when it’s discovered, social media lights up like the Fourth of July.

This is why what Bleeding Heart is doing is so annoying (I won’t say shocking, since it’s not as if they had that much trust of mine to begin with). First, no age statement. Second, the touted outturn given the lie by the bottle number. Third, the silence on additives. Well, they could have been simply careless, labelled badly, gave the wrong info the the PR boys in the basement; but carelessness or deception, what this means is that nothing they say now can be taken at face value, it’s like a wave of disbelief that washes over every and all their public statements about their rums. And so while I give the rum the score I do, I’d also advise any potential buyer to be very careful in understanding what it is that we’re being told the rum is, versus what it actually might be.

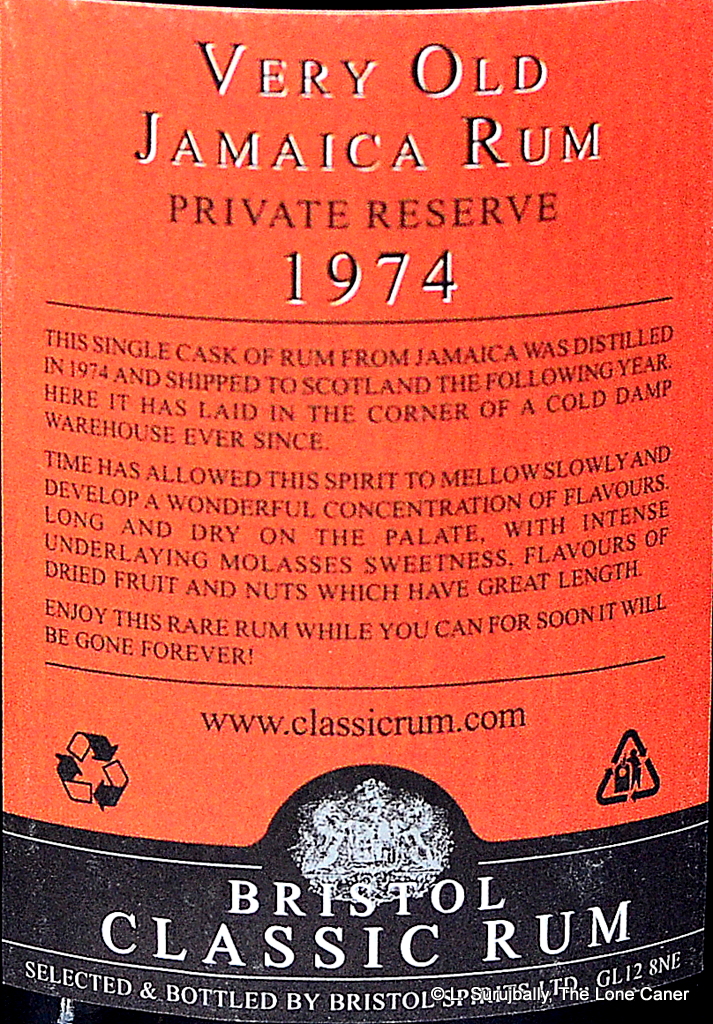

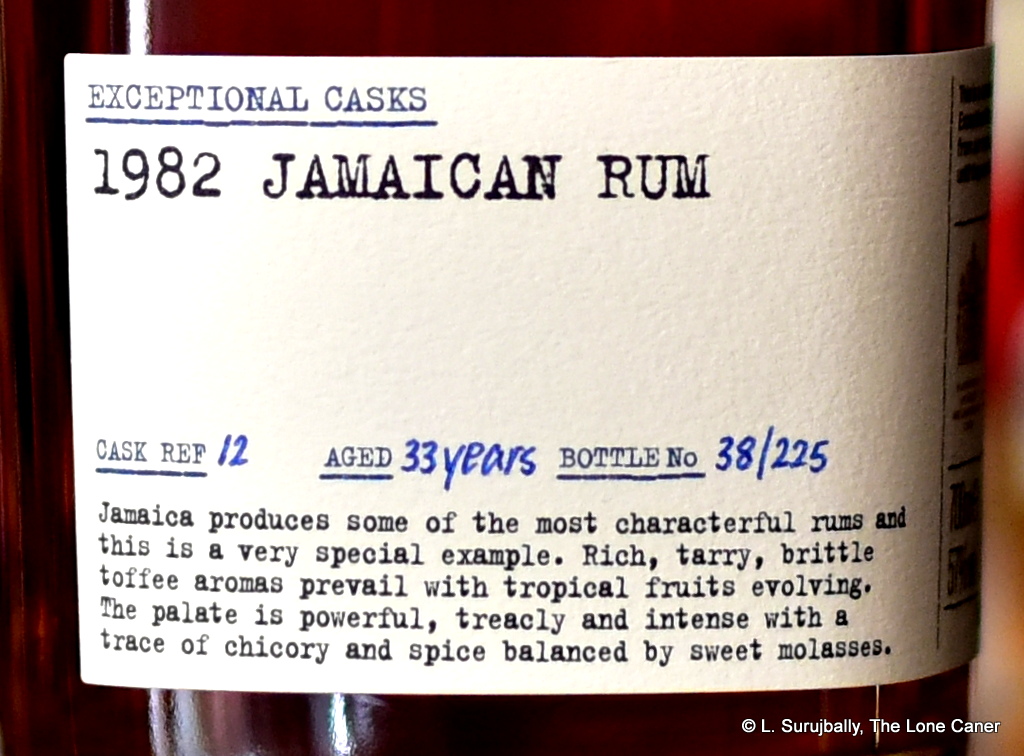

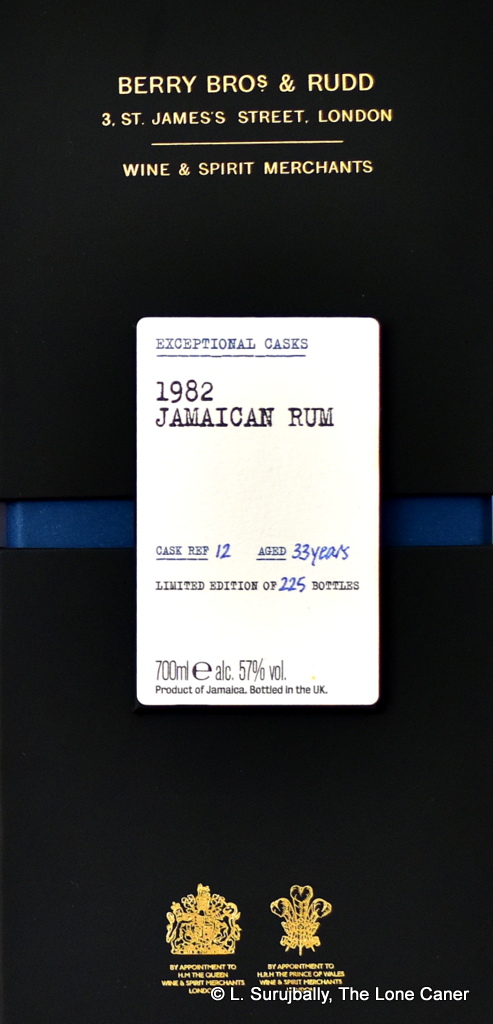

Nose – Quite a bit different from the strongly focussed Demerara profile of the Navy 70º we looked at before – had the label not been clear what was in it, I would have not guessed there was any Jamaican in here. The wooden stills profile of Guyana is tamed, and the aromas are prunes, licorice, black grapes and a light brininess. After a while some salt caramel ice cream, nougat, toffee and anise become more evident. Sharp fruits are held way back and given the absence of any kind of tarriness, I’d hazard that Angostura provided the Trinidadian component.

Nose – Quite a bit different from the strongly focussed Demerara profile of the Navy 70º we looked at before – had the label not been clear what was in it, I would have not guessed there was any Jamaican in here. The wooden stills profile of Guyana is tamed, and the aromas are prunes, licorice, black grapes and a light brininess. After a while some salt caramel ice cream, nougat, toffee and anise become more evident. Sharp fruits are held way back and given the absence of any kind of tarriness, I’d hazard that Angostura provided the Trinidadian component.  Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688

Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688 Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

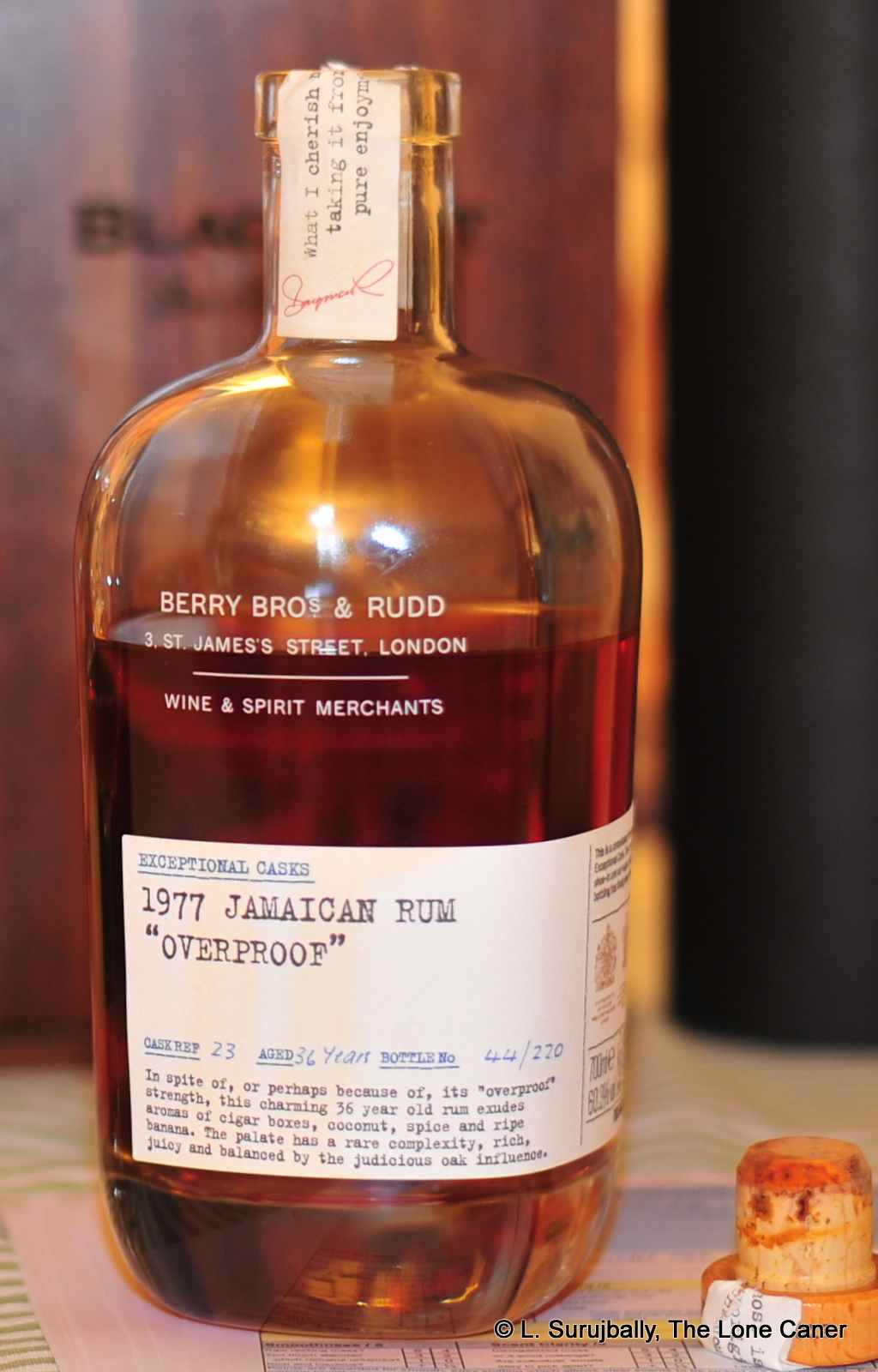

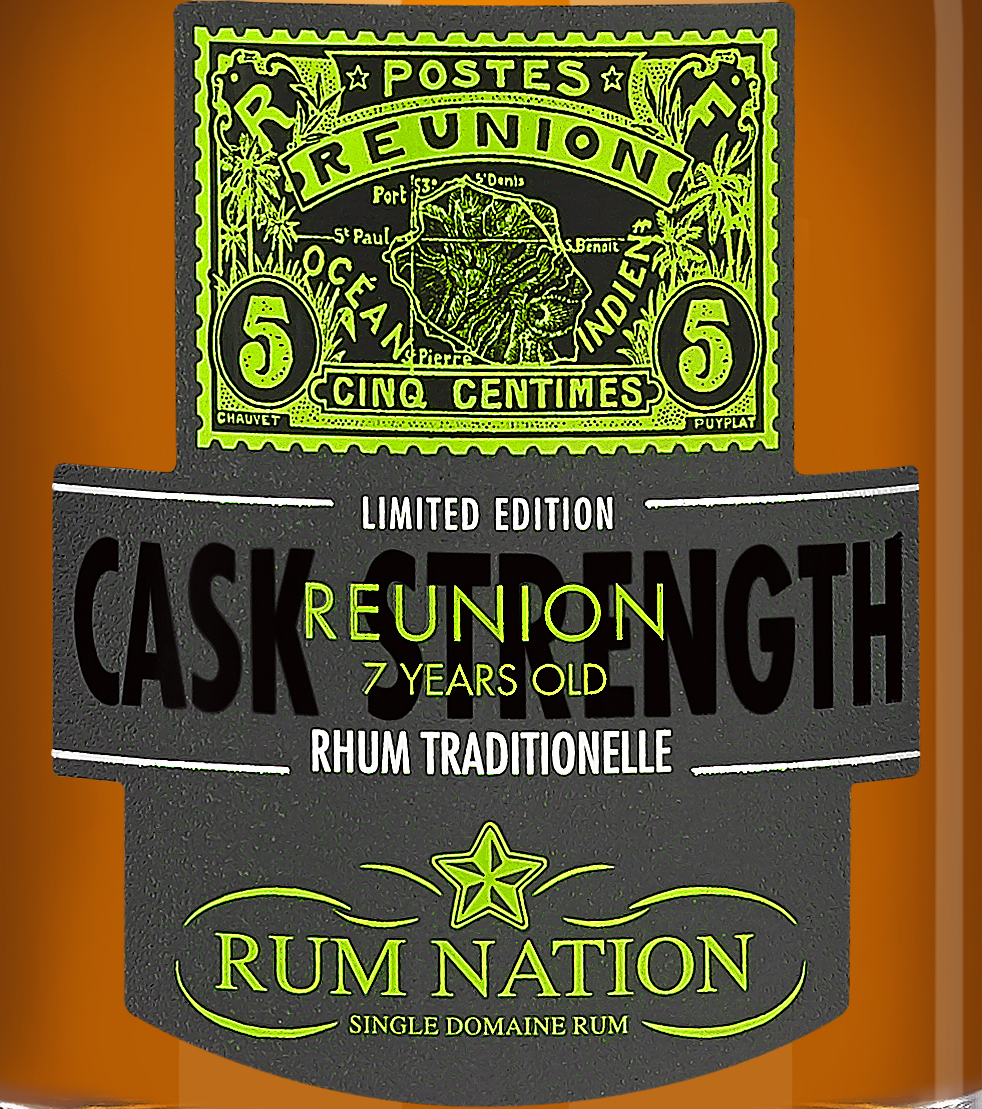

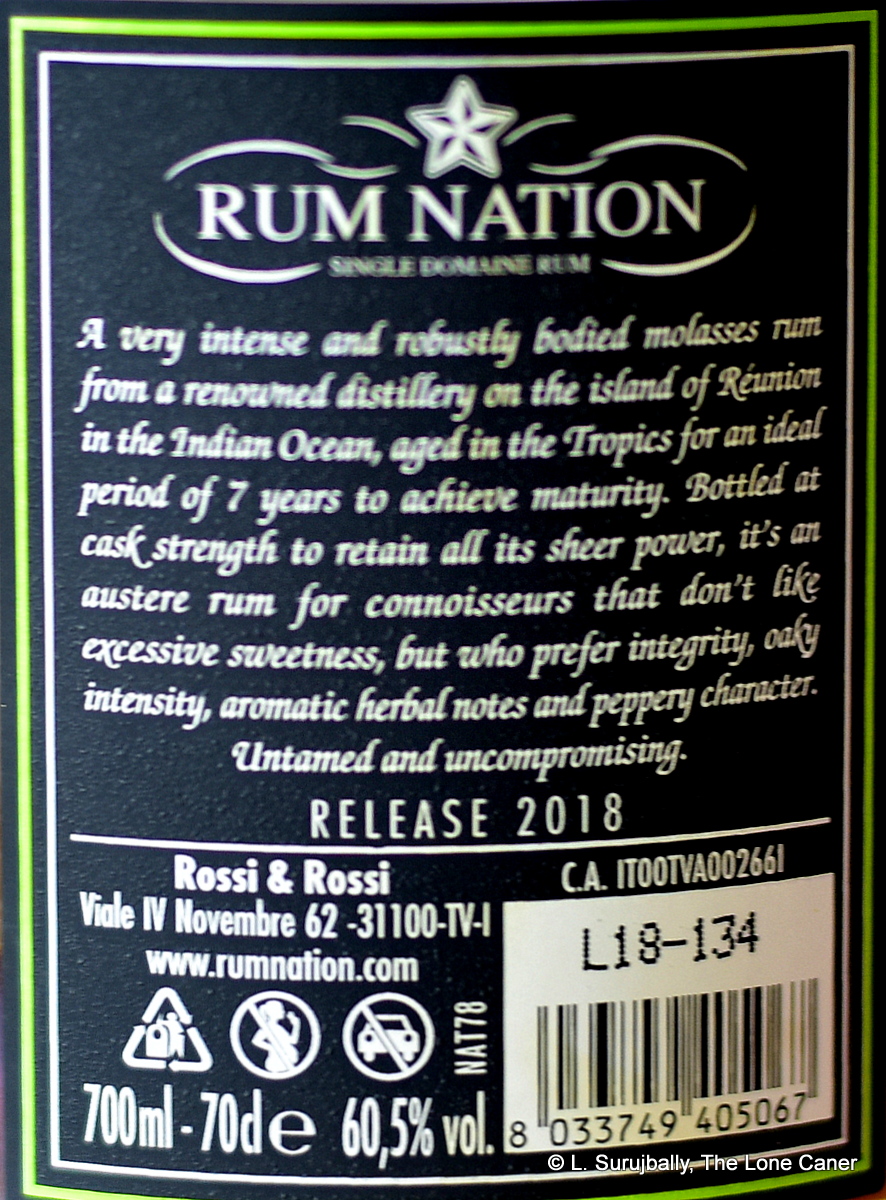

Some rums falter on the taste after opening up with a nose of uncommon quality – fortunately Rum Nation’s Réunion Cask Strength rum (to give it its full name) does not drop the ball. It’s sharp and crisp at the initial entry, mellowing out over time as one gets used to the fierce strength. It presents an interesting combination of fruitiness and muskiness and crispness, all at once – vanilla, lychee, apples, green grapes, mixing it up with ripe black cherries, yellow mangoes, lemongrass, leather, papaya; and behind all that is brine, olives, the earthy tang of a soya (easy on the vegetable soup), a twitch of wet cigarette tobacco (rather disgusting), bitter oak, and something vaguely medicinal. It’s something like a Hampden or WP, yet not — it’s too distinctively itself for that. It displays a musky tawniness, a very strong and sharp texture, with softer elements planing away the roughness of the initial attack. Somewhat over-oaked perhaps but somehow it all works really well, and the finish is similarly generous with what it provides — long and dry and spicy, with some caramel, stewed apples, green grapes, cider, balsamic vinegar, and a tannic bitterness of oak, barely contained (this may be the weakest point of the rum).

Some rums falter on the taste after opening up with a nose of uncommon quality – fortunately Rum Nation’s Réunion Cask Strength rum (to give it its full name) does not drop the ball. It’s sharp and crisp at the initial entry, mellowing out over time as one gets used to the fierce strength. It presents an interesting combination of fruitiness and muskiness and crispness, all at once – vanilla, lychee, apples, green grapes, mixing it up with ripe black cherries, yellow mangoes, lemongrass, leather, papaya; and behind all that is brine, olives, the earthy tang of a soya (easy on the vegetable soup), a twitch of wet cigarette tobacco (rather disgusting), bitter oak, and something vaguely medicinal. It’s something like a Hampden or WP, yet not — it’s too distinctively itself for that. It displays a musky tawniness, a very strong and sharp texture, with softer elements planing away the roughness of the initial attack. Somewhat over-oaked perhaps but somehow it all works really well, and the finish is similarly generous with what it provides — long and dry and spicy, with some caramel, stewed apples, green grapes, cider, balsamic vinegar, and a tannic bitterness of oak, barely contained (this may be the weakest point of the rum).

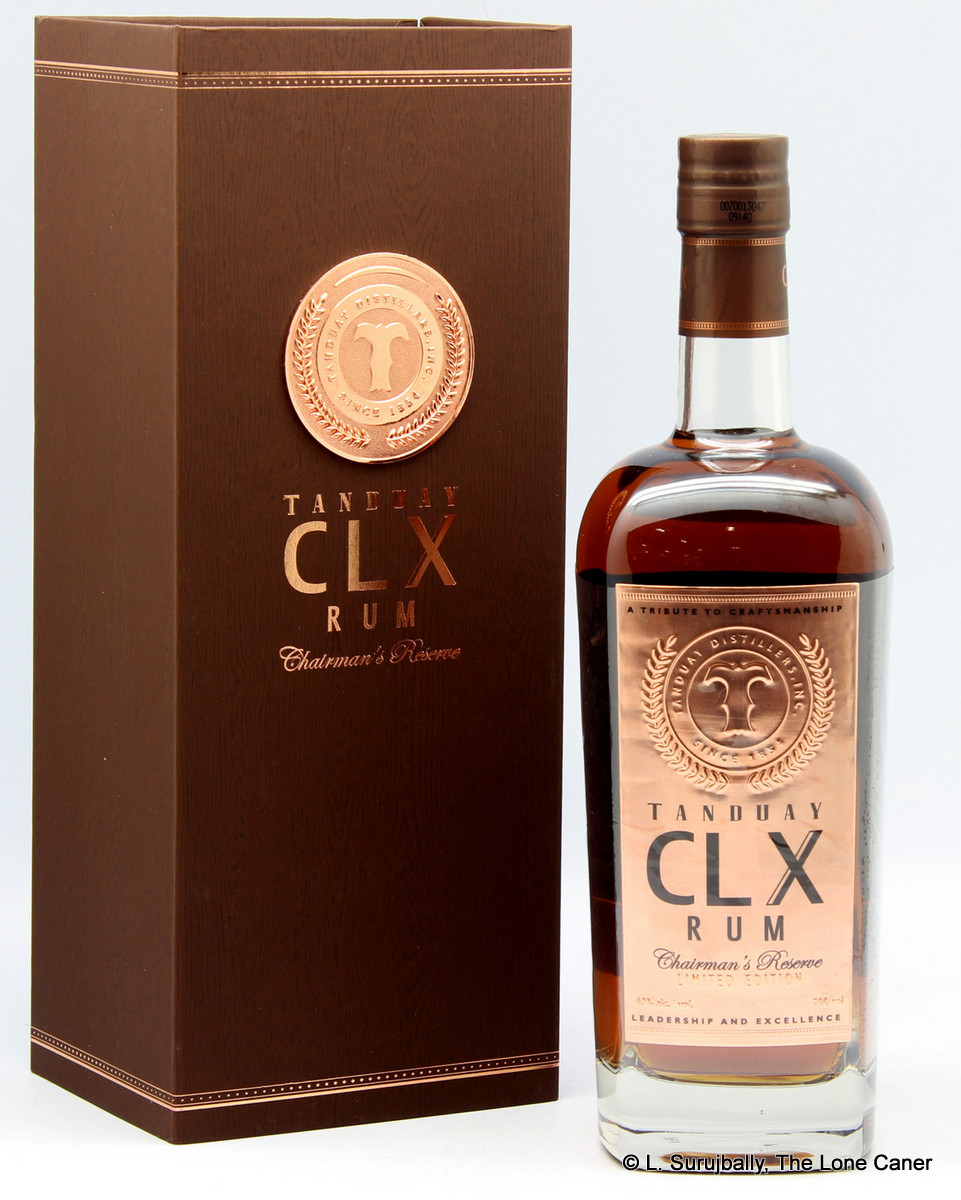

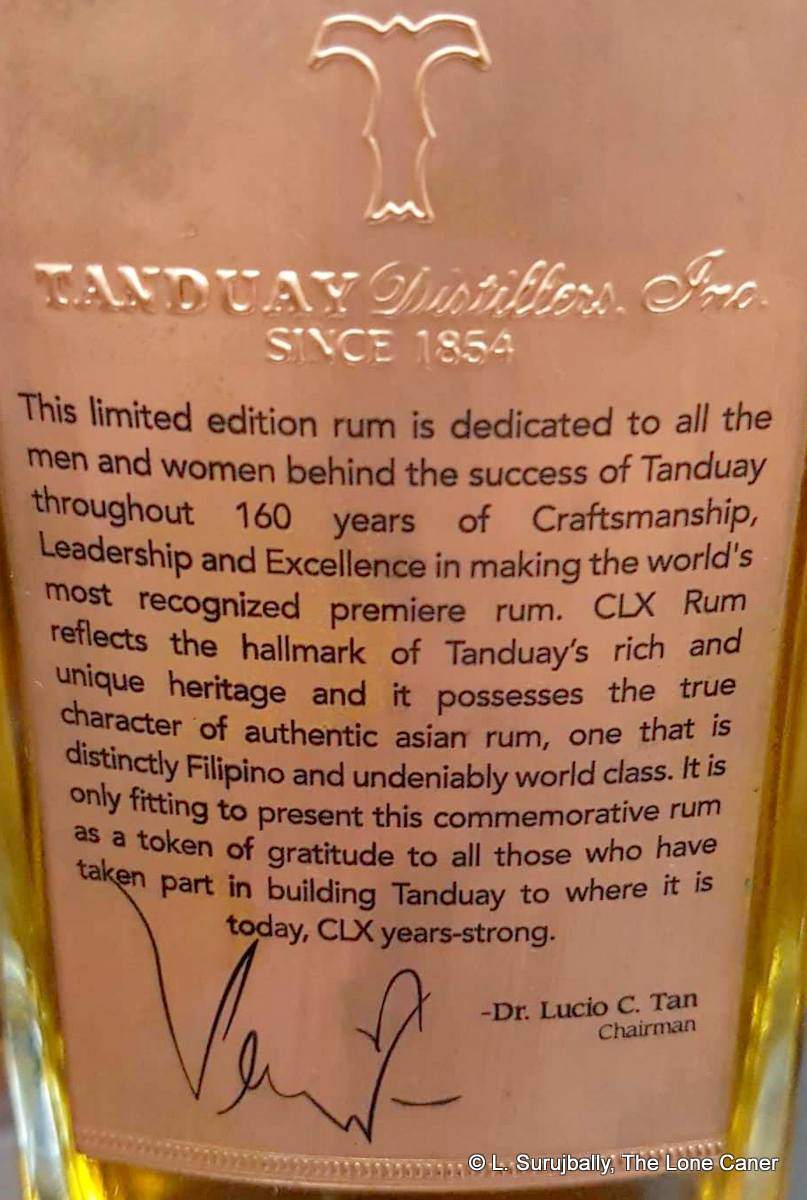

Anyway, when we’re done with do all the contorted company panegyrics and get down to the actual business of trying it, do all the frothy statements of how special it is translate into a really groundbreaking rum?

Anyway, when we’re done with do all the contorted company panegyrics and get down to the actual business of trying it, do all the frothy statements of how special it is translate into a really groundbreaking rum?

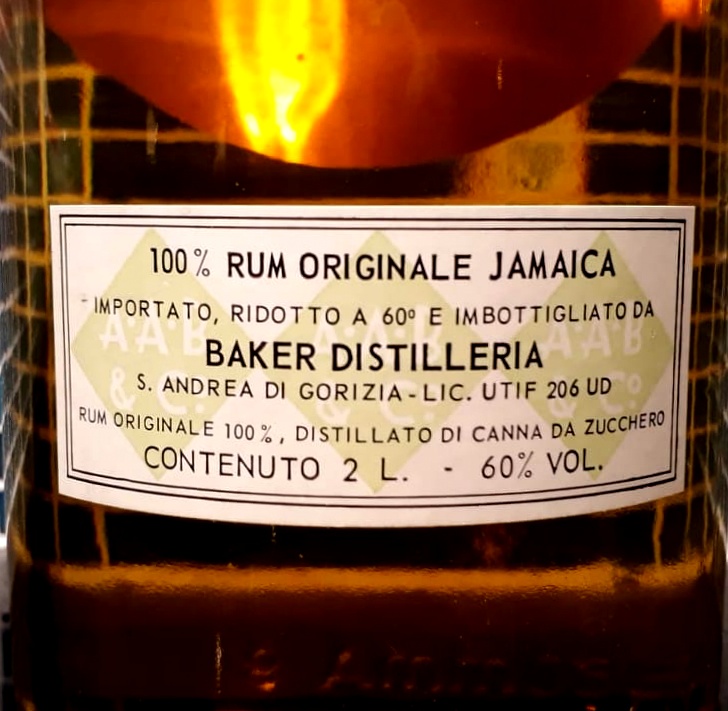

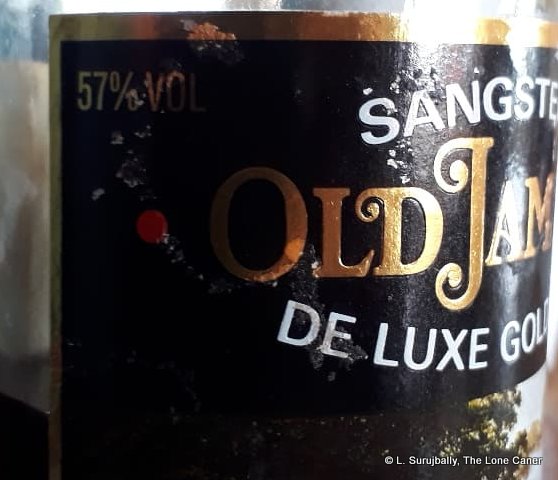

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued.

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued. Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.

Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.  Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones.

Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones.

And that creates a rum of uncommon docility. In fact, it’s close to being the cheshire cat of rums, so vaguely does it present itself. The soft silky nose was a watery insignificant blend of faint nothingness. Sugar water – faint; cucumbers – faint; cane juice – faint; citrus zest – faint (in fact here I suspect the lemon was merely waved rather gravely over the barrels before being thrown away); some cumin, and it’s possible that some molasses zipped past my nose, too fast to be appreciated.

And that creates a rum of uncommon docility. In fact, it’s close to being the cheshire cat of rums, so vaguely does it present itself. The soft silky nose was a watery insignificant blend of faint nothingness. Sugar water – faint; cucumbers – faint; cane juice – faint; citrus zest – faint (in fact here I suspect the lemon was merely waved rather gravely over the barrels before being thrown away); some cumin, and it’s possible that some molasses zipped past my nose, too fast to be appreciated.

Rumaniacs Review #080 | 0516

Rumaniacs Review #080 | 0516