When it comes to Australia and its rums, it’s likely that only two names immediately jump to mind (assuming you know of any at all and are not from there yourself): Bundaberg and Beenleigh. Both are relatively long-lived companies that predate many better-known producers founded much more recently in other parts of the world, yet it is only recently that awareness of them has climbed. Of course, this is in a large part due to association with or ownership by other major spirits companies with worldwide clout and visibility that can be leveraged, as well as social media trends.

Those two companies aside, however, few western consumers have tasted a wider selection of rums from Down Under. Australian rums don’t make it to rum shows or rum festivals (except in their own region) and pricing problems prohibit easy import or muling of bottles to and from the country, whether by distributors or individuals. But there is a vibrant and dynamic rum culture in Australia, and in the last two decades — paralleling the rum renaissance in the west — a host of small distilleries has cropped up, almost all single- or family-owned enterprises that make small batch pot still production. Because of the lack of any blogger or writer or reviewer in Australia who has a broad-based international readership, little of this has reached the attention of the wider rum world until very recently, when Mr. and Mrs. Rum issued the 2021 Australian Rum Advent Calendar. For the first time a wide variety of rums became available for people to try, and it was my good fortune to get hold of a box.

I systematically wrote the reviews one by one, and while they are now done, the thoughts they engender about Australian distillery culture and the rums they make, are too many to fit easily into a single review. Granted that twenty-plus reviews is hardly a complete sampling of the entire country, yet I feel that the points that occurred to me as the process continued — and at the end when I was summing up — are relevant in a more general context…more, at least, than just an observation on this or that distillery.

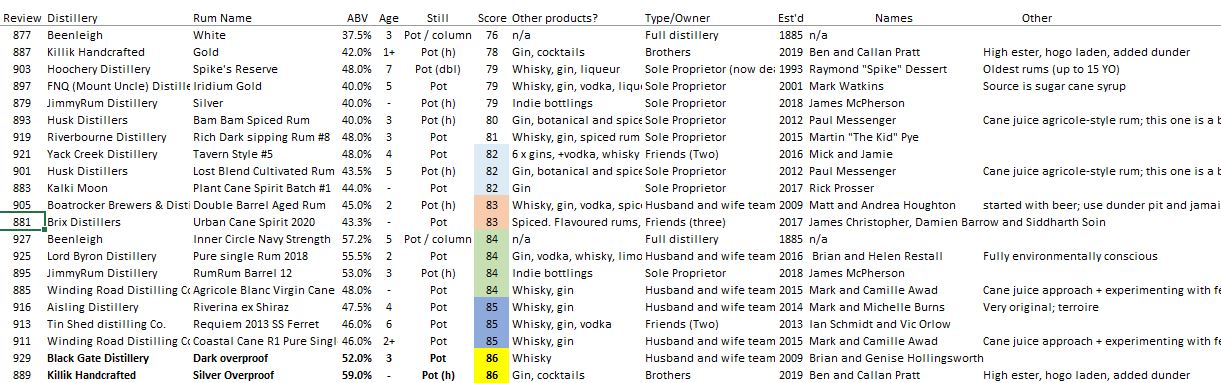

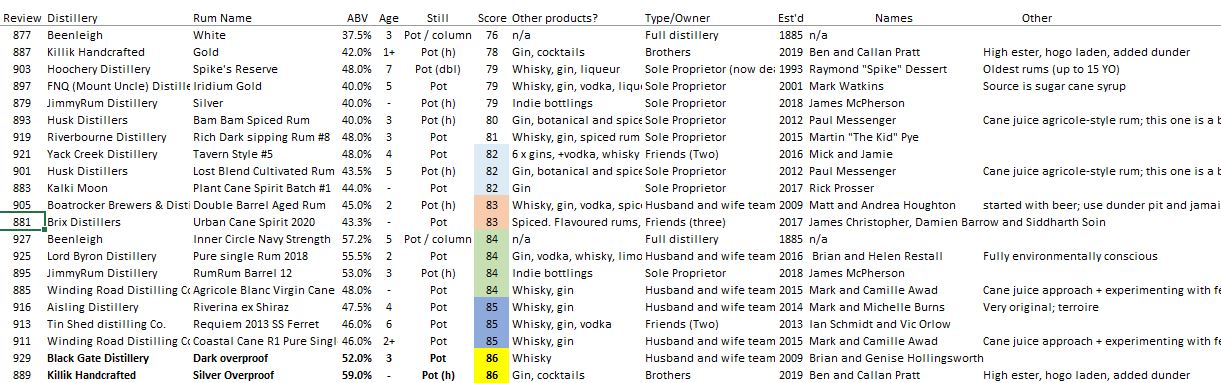

The first is evident from the tenor of the reviews: it’s something of a surprise how good the rums were (and are). Few scored below 80 points, and many were eye openers. I’ve tasted some really foul American, Canadian and Japanese rums which are thankfully not widely available, but here, small and local distillers I had never heard of before were making impressive young rums and cane juice spirits that held themselves up well even when rated against Caribbean rums of greater fame and heritage. Some were essays in the craft, to be sure, and in many cases the rough edges remained visible, the rums too young, the style not yet complete; yet I firmly believe that many will only get better as time goes on, and skills and technique get more refined — and hopefully they will get the attention and kudos they deserve.

The operations making these rums are, for the most part, micro-distilleries, and serve a regional market (some are only at a town- or state-level). A few large ones like Beenleigh and Bundaberg export abroad, but this is an exceptional situation. What characterises most of the distilleries that produced these rums is that they are either sole-proprietorships, husband-and-wife teams, or set up by a few friends, and while I don’t know anything about their financial situation, it seems to me that what they do is a personal thing, a labour of love, and their own funds and families and friendship networks are quite invested in the success of what is at end a small business that has some unique restrictions.

For one, they are hampered by the “ageing law”: rum may not be called “rum” until it’s been aged for at least two years in Australia, a law that has been on the books since 1906. Initially enacted to prevent low grade, poorly made, unaged moonshine — which quite literally, could be and often was, lethal — unscrupulously being sold to unknowing patrons, it is not completely a relic of rougher colonial times as I had thought. Alcoholism and abuse by both buyers and sellers is still a problem today and this is one reason why the law remains, and taxes on alcohol remain quite high.

The law’s intention (if not its ultimate effect) was and is to remove unaged full-proof rum from easy distribution to vulnerable segments of the population, though of course it only really affects legally established distilleries, not outback hoocheries beyond the easy reach of regulators, lawmakers or taxmen. But the unintended consequence of this is that one of the potential revenue spinners of new distilleries which need cash flow to recoup their substantial initial capital outlay – the sale of unaged white rum, especially if made from cane juice – is removed, as it cannot be sold as “rum”.

Inventive and agile distillers have gotten around this issue by releasing such rums as “cane spirit” yet undoubtedly sales are foregone by application of a law which has not kept pace with developments in the wider rumiverse, where such cane spirits are called rums. Elsewhere in the world, they also go by names like charanda, grogue, clairin, aguardiente or agricole and have devoted consumers who prize the authentic nature of the spirits produced in such a fashion. The problem in Australia as elsewhere, is, of course, that those not already into rum won’t make the connection between these varieties and “real” rum, which again impacts sales and hampers recognition.

The two-year rule therefore prioritises and incentivises aged rums and other spirits without such restrictions, and this means that for at least those two years (likely more – James McPherson suggests five) no rum distillery can really make cash flow on rum alone while its stock is maturing. This requires Australian distillers to focus on other money-makers that can provide more immediate revenues: the most common of these is gin, which is why the gin varieties and volumes in Australia are so great. Unaged cane spirit is another. However, unaged bulk sales abroad — where 10,000-litre or greater iso-containers are the norm — are usually not feasible, because volumes of rum which are distilled are relatively small, sometimes as little as a few thousand litres annually.

And it must be conceded that most distillers are in it to make whiskies, not rums, and like the American micro distillers I’ve mentioned before, rums are a sideshow, if not a complete afterthought – there are many more whisky distillers to be found on Google Maps than rum-focused ones, for example. Some distillers make yet other products in addition to gins and whiskies — spiced spirits, vodkas, limoncello, liqueurs, etc. But the consequence of all this diversity is very much the same as it is in America: focus is diluted and expertise is scattershot, and deep experience, while not absent, is thin on the ground and takes longer to develop than in an operation where it’s rum, and only rum that’s the first spirit of make (I’m not criticising distillers’ necessary choices, only mentioning this is an inevitable outgrowth of the rules).

But seen from the outside, clearly there is talent and to spare in Australia and a genuine love of rums. After all, people keep drinking the stuff, and if it’s being bought, it’ll continue getting made. It didn’t matter whether it was a hundred-year-old distillery, or one established less than a decade ago: almost all the rums I tried were of good quality, with some real standouts. The size or age of the distillery had at best a marginal impact on quality — for example, Killik (founded in 2019) had an unaged white rum was way better than the venerable Beenleigh’s 3 Year Old White, and Black Gate’s Dark Overproof (from a company established in 2009) was its equal though aged.

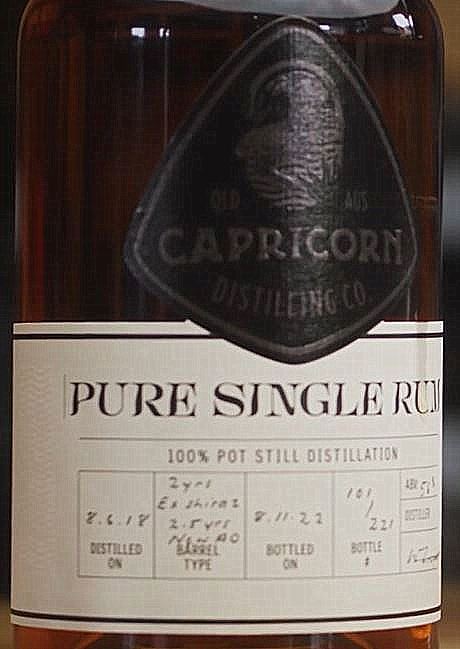

The key determinants of really good Australian rums seemed to be a combination of their proof points (stronger was mostly better than weaker, though not always) and the ability of their distillers to think a little outside the box, play around and go for something new – they pounced on niche techniques to seek competitive advantage. Since just about all the rums came from a pot still or a hybrid pot/column and had the 2-year age restriction (Hoochery’s Spike’s Reserve aged 7 years and Tin Shed’s Requiem at 6, were the oldest), it was fermentation and source material that helped carry the flag, and high scoring distilleries like Winding Road, Aisling, Tin Shed, Black Gate and Killik had points of uniqueness in their production methodology unrelated to ageing. Some used cane juice or syrup rather than molasses, others went into longer ferments or used dunder and relentlessly experimented to get “Jamaican style” rums out the other end, while still others played around with finishes and odd casks.

That said, a not unreasonable question is whether they display anything specific to themselves, something uniquely Australian that would allow someone with even a smidgen of experience to stand up straight and immediately identify a rum from Oz. After all, say what you will about the Bundie, one sniff of that thing and after you stop spilling your guts and recover your sight, you’d instantly know it for what it was, sight unseen. Are the ones I’ve been reviewing anything like that?

In my personal opinion, not really. In fact, the strongest impression I took away from this admittedly limited sample set — and one which had been tickling me since I tasted the first indie bottlers’ Beenleighs years ago — is how modern and contemporary they tasted, and that’s both a compliment and an observation. While the quality was indisputably there, the tasted profiles often conformed to the formal regional “styles” already popularised by existing countries and their flagship distilleries. To put it another way, it was hard for me to try these rums blind (as I did) and not instinctively see Barbados, Antigua, Trinidad, Panama, or St. Lucia, depending on which it was. They have the same nature – much improved by being fully pot still distillate, to be sure — that makes them fine drinks, but not clearly identifiable as being from Australia. Even the ones that suggested Jamaica were like that (though more Appleton than Hampden or Worthy Park, it must be conceded). The most distinctive were the unaged agricole-style cane juice rums like Winding Road’s Coastal Cane, or high ester unaged rums like Killik’s Silver Overproof. Those you could tell came from someplace new, someplace damned fine.

Does this matter? Not entirely, because good rums are good rums and people will always gravitate towards tasty spirits that don’t break the bank. It’s only superdorks, ur-geeks and rabid rum aficionados (did somebody say “Caner!” ?? Hush, ye snickerers) that make these superfine distinctions. However, for a more globally recognized Australian rum category to truly emerge will to some extent depend on being able to sway rum lovers the world around on not only quality, but uniqueness: because, why would anyone in the US or Europe buy an Australian-made Jamaica-style rum when the real deal from Hampden or WP or Appleton can be had more easily and for less? I honestly hope that a localised, Australia-centric style of rum will slowly come into focus because of such pressures, and a move away from already existing styles will help.

Wrapping up, then: notwithstanding all the remarks above, I loved these rums. Almost without exception, every single one of the samples in the calendar displayed a quality that for distilleries so small and often so young, was nothing short of astounding. They are not yet top-tier, bestest-of-the-restest, but damn, they did come close in places, they were good for what they were, and will only get better. The hard and often unappreciated work — of so many individual distillers, so many obsessive rummies and their patiently eye-rolling spouses, who experiment without rest or reward day in and day out — really has achieved something wonderful in Australia. I hope to lay hands on more in the years to come, or at the very least more advent calendars as they become available. Because good or bad or indifferent or spectacular, it’s worth it to see a new rum region rise up, snap into focus and add new some fruit to the great rum tree. We should all be grateful for that, no matter where we live.

Further reading

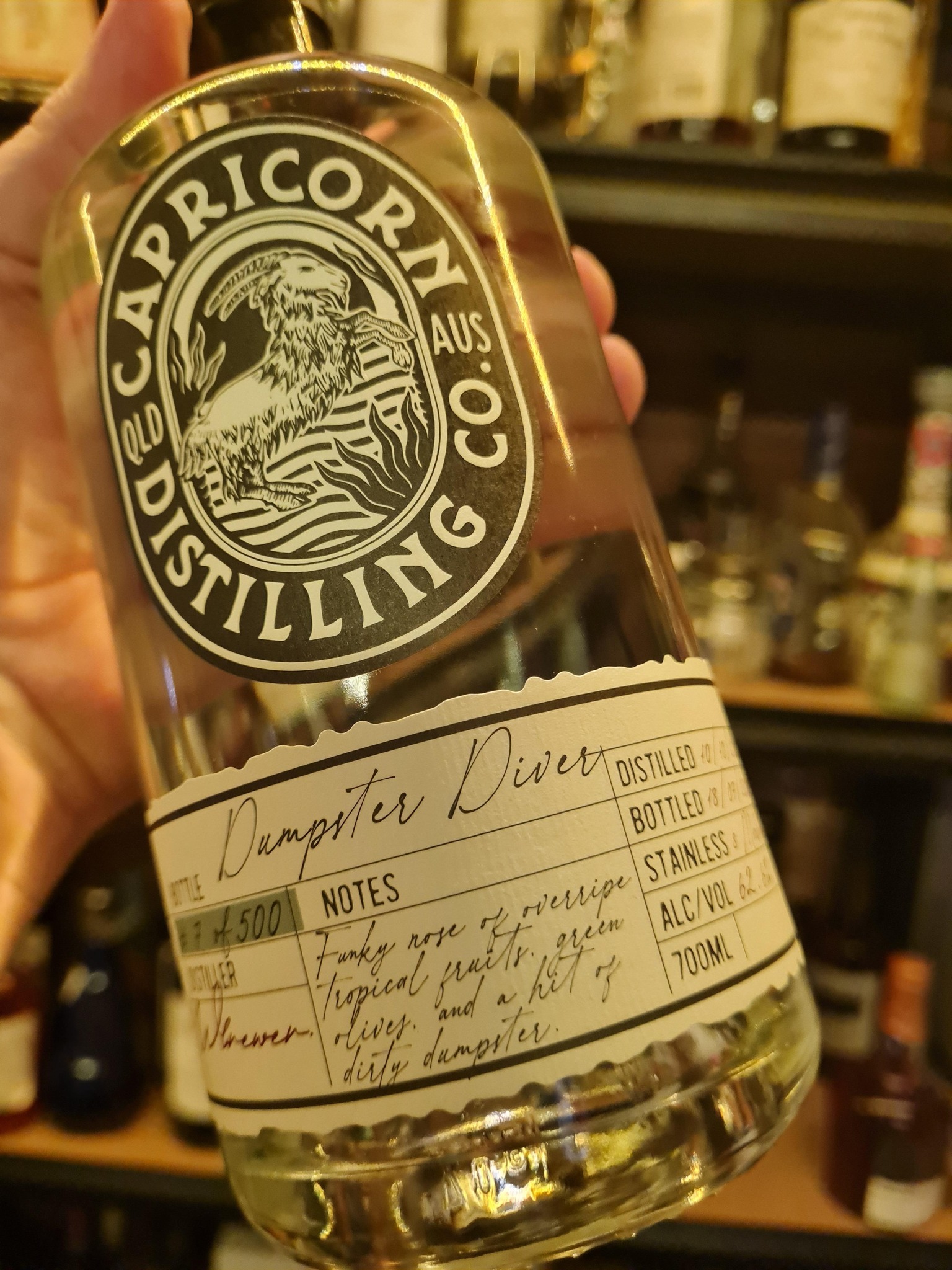

If that sounds interesting, wait until you nose it, because while it’s not quite as well rounded as the Pure Single Rum, it’s hot, it’s spicy, it’s clean as new steel, and really crisp. There’s a sense of sparkling wine about it – chianti, Riesling, plus some 7up, and pineapples. Lemony cumin, ginger, florals, cinnamon, which slowly merges with a damper aroma of rain on hot clay bricks and then softens into coconut shavings, oatmeal cookies and white chocolate crusted with almonds. The clear metallic sweat of someone who’s been exerting themselves in very cold weather after just having had a bath (yeah, I know how barmy that sounds). Juicy and ripe white fruits – papaya, guavas, pears, green apples and a few slices of pineapple. This is clearly a rum that enjoys Christmas.

If that sounds interesting, wait until you nose it, because while it’s not quite as well rounded as the Pure Single Rum, it’s hot, it’s spicy, it’s clean as new steel, and really crisp. There’s a sense of sparkling wine about it – chianti, Riesling, plus some 7up, and pineapples. Lemony cumin, ginger, florals, cinnamon, which slowly merges with a damper aroma of rain on hot clay bricks and then softens into coconut shavings, oatmeal cookies and white chocolate crusted with almonds. The clear metallic sweat of someone who’s been exerting themselves in very cold weather after just having had a bath (yeah, I know how barmy that sounds). Juicy and ripe white fruits – papaya, guavas, pears, green apples and a few slices of pineapple. This is clearly a rum that enjoys Christmas.