One of the things that irritates me about this blended rum from Guyana which Rum Nation released in 2019, is the carelessness of the front label design. I mean, seriously, how is it possible that “British Guyana” can actually be on a rum label in the 21st century, when Guyana has not been British anything since 1966 and when it was, it was spelled “Guiana”? Are designers really that clueless? And lest you think this is just me having a surfeit of my daily snarky-pills, think about it this way: if they couldn’t care enough to get their facts right about stuff so simple, what else is there on the label I can’t trust?

Still: I am grateful that the back label is more informative. Here, it is clearly spelled out that the rum is a blend of distillate from the French Savalle still, the (Enmore) wooden coffey still and the (Port Mourant) double wooden pot still, and this blend was aged for four years in the tropics (in British Guyana, one may assume) before undergoing a secondary European maturation for six years in ex-oloroso casks, and then decanted into 2,715 bottles, each at 56.4% ABV. What this is, then, is a bottling similar to DDL’s own experimental blended Rares, which has dropped completely out of sight since its introduction in 2019. A similar fate appears to have befallen this one since I don’t know the last time I saw one pop up at auction, let alone on social media.

But perhaps it’s an undiscovered steal, so let’s look deeper. Nose first: it’s surprisingly simple, even straightforward. It’s warm and thick, and represents the wooden stills in fine style – dusty, redolent of breakfast spices, oak and vanilla at first, then allows additional aromas of coffee grounds, raisins, dried orange peel dark fruits, licorice. I wouldn’t go so far as to say the oloroso influence is dominating though, and in fact it seems rather dialled down, which is unexpected for a rum with a six year sleep in sherry barrels.

I do, on the other hand, like the taste. It’s warm and rich and the Enmore still profile – freshly sawn lumber, sawdust, pencil shavings – is clear. Also sour cream, eggnog, and bags of dried, dark fruits (raisins, prunes, dried plums) mix it up with a nice touch of sandalwood. It takes its own sweet time getting the the point and is a little discombobulated throughout, but I can’t argue with the stewed apples, dried orange peel, ripe red guavas and licorice – it’s nice. The finish is quite solid, if unexceptional: it lasts a fair bit, and you’re left with closing notes of licorice, oak chips, vanilla, dried fruit and black cake.

I do, on the other hand, like the taste. It’s warm and rich and the Enmore still profile – freshly sawn lumber, sawdust, pencil shavings – is clear. Also sour cream, eggnog, and bags of dried, dark fruits (raisins, prunes, dried plums) mix it up with a nice touch of sandalwood. It takes its own sweet time getting the the point and is a little discombobulated throughout, but I can’t argue with the stewed apples, dried orange peel, ripe red guavas and licorice – it’s nice. The finish is quite solid, if unexceptional: it lasts a fair bit, and you’re left with closing notes of licorice, oak chips, vanilla, dried fruit and black cake.

Overall, it’s a good rum, though I believe it tries for too much with the three stills’ distillates and the long sherry barrel ageing. There’s a lot going on but it doesn’t quite snap together into a harmonious whole. There’s always too much or too little of one or other element here, the sherry influence is inconsistent at best, and it keeps charging around in a confusing mishmash of rum that tastes okay but never settles down to allow us as drinkers to come to grips with it. This is an observation also levelled at DDL’s experimental rares, by the way, but not Velier’s “blended in the barrel” series of later Guyanese rums which set the bar quite high for such blends.

Clearing away the dishes, then, consider it as a decent blend, something for those who want to take a flier on an El Dorado rum that isn’t actually one of them, or a less expensive, younger Velier blend. Think of it as a stronger and slightly older version of ED’s own 8 Year Old, lacking only DDL’s mastery of their blending practice to score higher. That is at best a guarded endorsement, but it’s all the rum really merits

(#814)(82/100)

Background

Rum Nation is that indie rum company founded by Fabio Rossi back in 1999 in Firenze (in NE Italy), and if they ever had a killer app of their own, it was those very old Demeraras and Jamaican “Supreme Lord” rums which were once wrapped in jute sacking and ensconced in wooden boxes. Rum Nation was one of the first of the modern rum independents that created whole ranges of rums and not just one or two single barrel expressions: from affordable starter bottles to ultra-aged products, and if they aged some of their releases in Europe, well, at the time that was hardly considered a disqualifier.

By 2016, however, things had started to change. Velier’s philosophy of pure tropically-aged rums had taken over the conceptual marketplace at the top end of sales, and a host of new and scrappy European independents had emerged to take advantage of rum’s increasing popularity. Rum Nation took on the challenge by creating a new bottle line called the Rare Collection – the standard series of entry level barroom-style bottles remained, but a new design ethos permeated the Rares – sleeker bottles, bright and informative labelling, more limited outturns. In other words, more exclusive. Many of these rums sold well and kept Rum Nation’s reputation flying high. People of slender means and leaner purses kept buying the annual entry-level releases, while connoisseurs went after the aged Rares.

Two years later, Fabio was getting annoyed at being sidetracked from his core whisky business (he owns Wilson & Morgan, a rebottler), and he felt the indie rum business was more trouble than it was worth. Too, he was noticing the remarkable sales of the Ron Millonario line (a light bodied, rather sweet rum out of Peru), which, on the face of it, should not be anywhere near as successful as it was. And so, finally, he divested himself of the Rum Nation brand altogether, selling out to a small group of Danish investors. He kept the Millonario brand and has an arrangement to rep RN at various rum festivals (which was how I saw him in 2019 in Berlin), but the era of his involvement with the company formed two decades earlier, is now over.

…which might explain why the label was done that way.

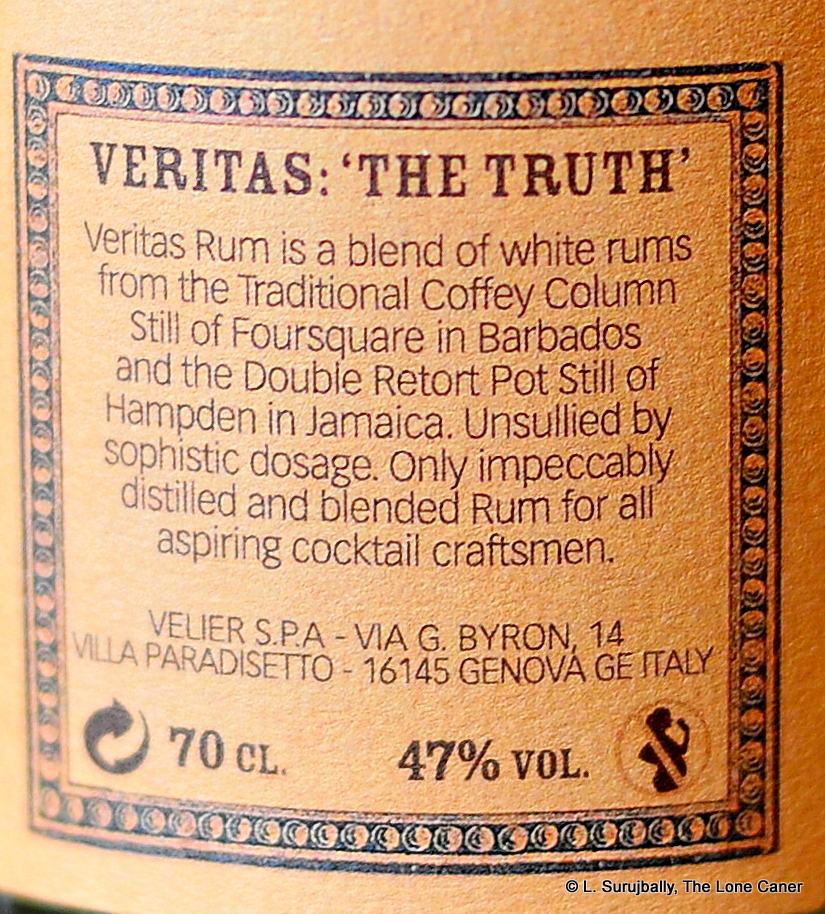

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title. Rumaniacs Review #120 | 0757

Rumaniacs Review #120 | 0757 Colour – Gold

Colour – Gold Rumaniacs Review #119 | 0756

Rumaniacs Review #119 | 0756 Colour – Dark gold

Colour – Dark gold Rumaniacs Review #118 | 0755

Rumaniacs Review #118 | 0755 Colour – Mahogany

Colour – Mahogany

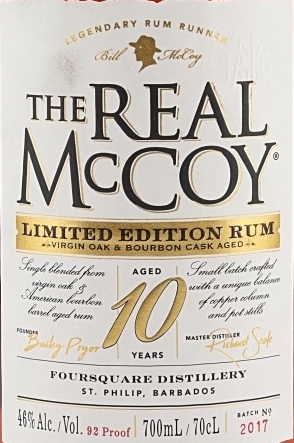

On the palate, the slightly higher strength worked, up to a point. It’s a lot better than 40%, and allowed a certain heft and firmness to brush across the tongue. This then enhanced a melded mishmash of fruits – watermelon, bananas, papaya – plus cocoa butter, coconut shavings in a Bounty chocolate bar, honey and a pinch of salt and vanilla, all of which got shouldered aside by the tannic woodiness. I suspect the virgin oak is responsible for that surfeit, and it made the rum sharper and crisper than those McCoy and Foursquare rums we’re used to, not entirely to the rum’s advantage. The finish summed of most of this – it was dry, rather rough, sharp, and pretty much gave caramel, vanilla, light fruits, and some last tannins which were by now starting to fade. (Subsequent sips and a re-checks over the next few days don’t appreciably change these notes).

On the palate, the slightly higher strength worked, up to a point. It’s a lot better than 40%, and allowed a certain heft and firmness to brush across the tongue. This then enhanced a melded mishmash of fruits – watermelon, bananas, papaya – plus cocoa butter, coconut shavings in a Bounty chocolate bar, honey and a pinch of salt and vanilla, all of which got shouldered aside by the tannic woodiness. I suspect the virgin oak is responsible for that surfeit, and it made the rum sharper and crisper than those McCoy and Foursquare rums we’re used to, not entirely to the rum’s advantage. The finish summed of most of this – it was dry, rather rough, sharp, and pretty much gave caramel, vanilla, light fruits, and some last tannins which were by now starting to fade. (Subsequent sips and a re-checks over the next few days don’t appreciably change these notes). This is a rum that has become a grail for many: it just does not seem to be easily available, the price keeps going up (it’s listed around €300 in some online shops and I’ve seen it auctioned for twice that amount), and of course (drum roll, please) it’s released by Richard Seale. Put this all together and you can see why it is pursued with such slack-jawed drooling relentlessness by all those who worship at the shrine of Foursquare and know all the releases by their date of birth and first names.

This is a rum that has become a grail for many: it just does not seem to be easily available, the price keeps going up (it’s listed around €300 in some online shops and I’ve seen it auctioned for twice that amount), and of course (drum roll, please) it’s released by Richard Seale. Put this all together and you can see why it is pursued with such slack-jawed drooling relentlessness by all those who worship at the shrine of Foursquare and know all the releases by their date of birth and first names.

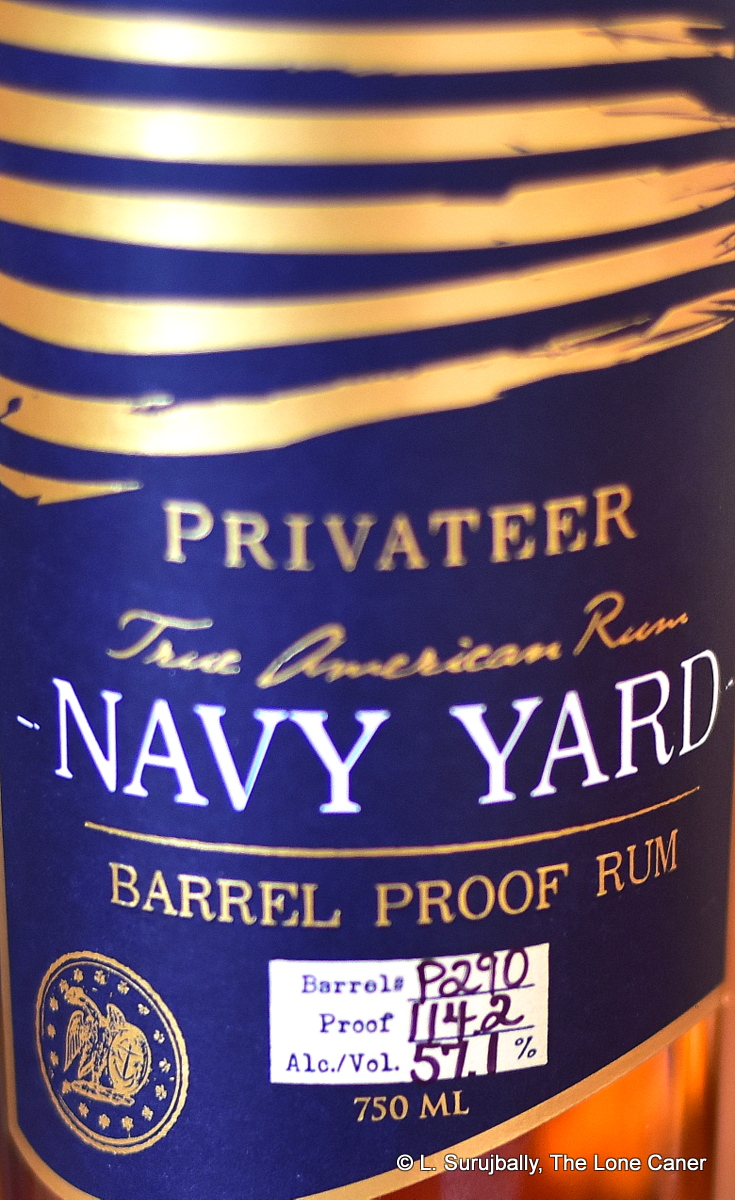

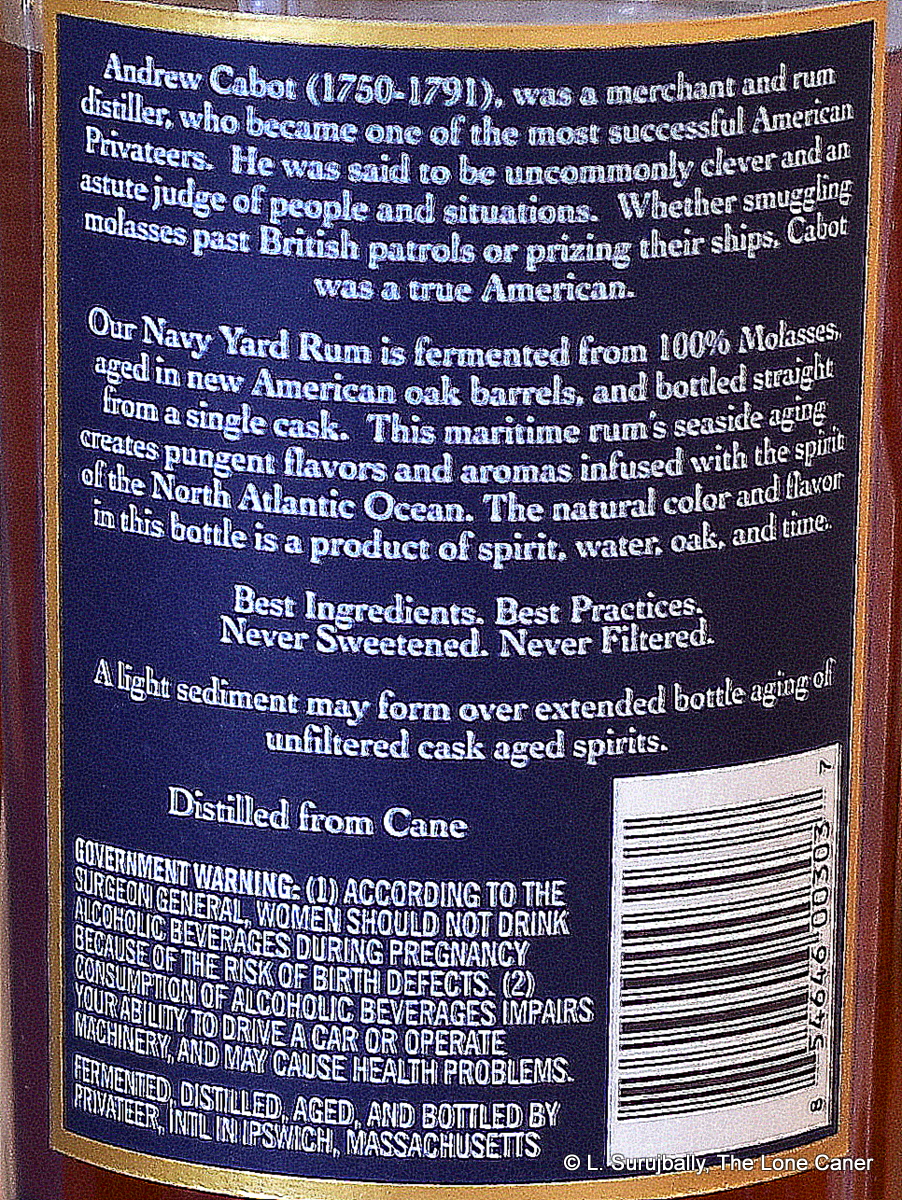

Privateer

Privateer Overall, it’s a good young rum which shows its blended philosophy and charred barrel origins clearly. This is both a strength and a weakness. A strength in that it’s well blended, the edges of pot and column merging seamlessly; it’s tasty and strong, with just a few flavours coming together

Overall, it’s a good young rum which shows its blended philosophy and charred barrel origins clearly. This is both a strength and a weakness. A strength in that it’s well blended, the edges of pot and column merging seamlessly; it’s tasty and strong, with just a few flavours coming together

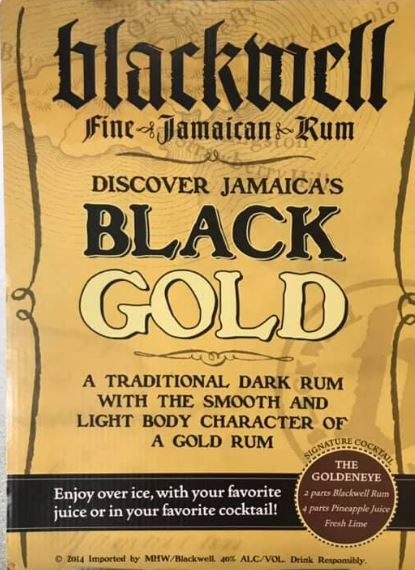

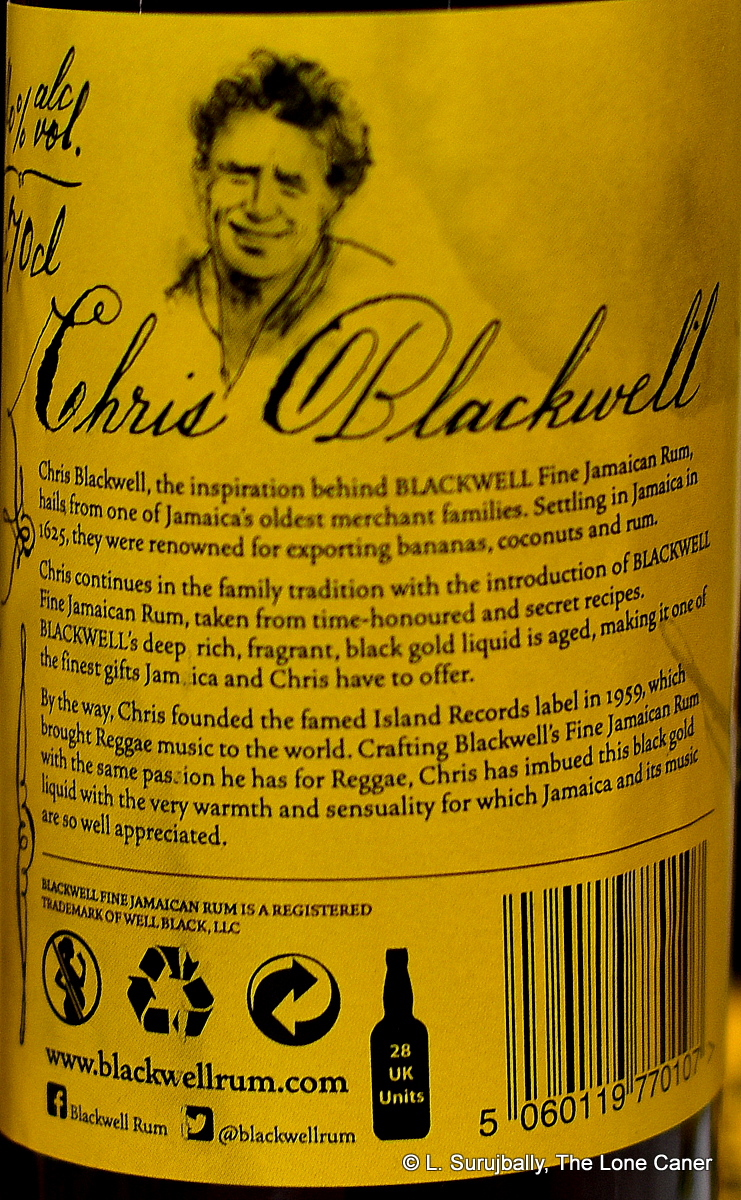

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in  With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

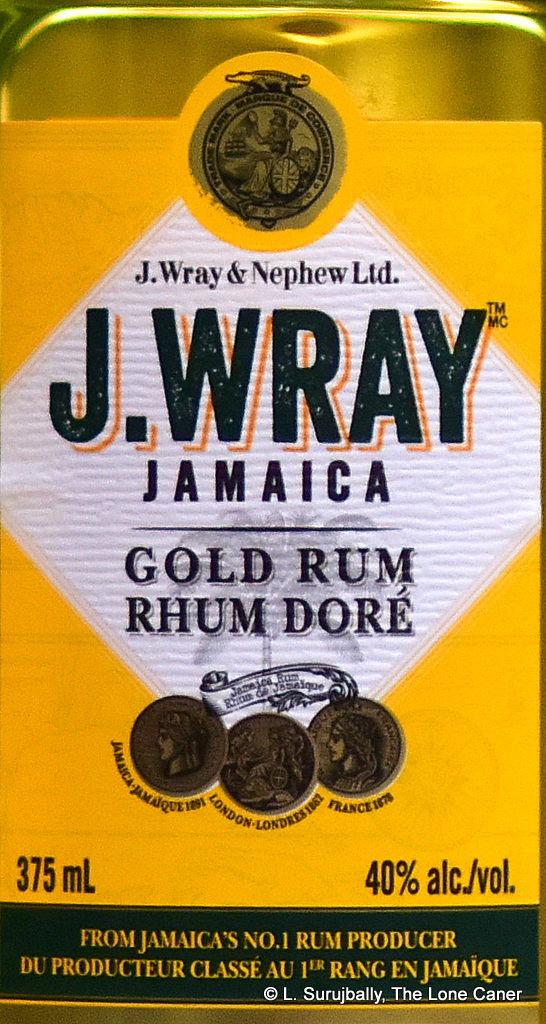

And why shouldn’t they? It’s a fifteen year old rum issued at a relatively affordable price, and is widely available, has been around for decades and has decent flavour chops for those who don’t have the interest or the coin for the limited edition independents.

And why shouldn’t they? It’s a fifteen year old rum issued at a relatively affordable price, and is widely available, has been around for decades and has decent flavour chops for those who don’t have the interest or the coin for the limited edition independents.

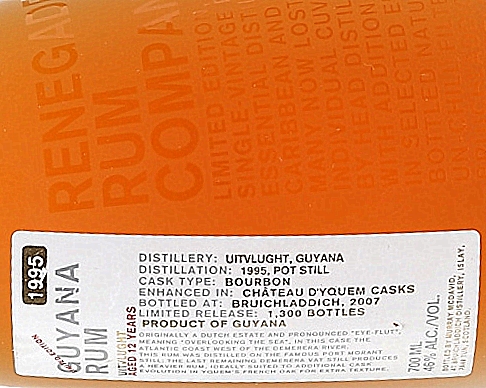

Knowing the Demerara rum profiles as well as I do, and having tried so many of them, these days I treat them all like wines from a particular chateau…or like James Bond movies: I smile fondly at the familiar, and look with interest for variations. Here that was the way to go. The nose suggested an almost woody men’s cologne: pencil shavings, some rubber and sawdust a la PM, and then the flowery notes of a bull squishing happily way in the fruit bazaar. It was sweet, fruity, dark, intense and had a bedrock of caramel, molasses, toffee, coffee, with a great background of strawberry ice cream, vanilla, licorice and ripe yellow mango slices so soft they drip juice. The balance between the two stills’ output was definitely a cut above the ordinary.

Knowing the Demerara rum profiles as well as I do, and having tried so many of them, these days I treat them all like wines from a particular chateau…or like James Bond movies: I smile fondly at the familiar, and look with interest for variations. Here that was the way to go. The nose suggested an almost woody men’s cologne: pencil shavings, some rubber and sawdust a la PM, and then the flowery notes of a bull squishing happily way in the fruit bazaar. It was sweet, fruity, dark, intense and had a bedrock of caramel, molasses, toffee, coffee, with a great background of strawberry ice cream, vanilla, licorice and ripe yellow mango slices so soft they drip juice. The balance between the two stills’ output was definitely a cut above the ordinary.

I make this last observation because of its unrefined nature. Even at standard strength, it noses rather raw and jagged, even harsh. There are initial aromas of light glue, rotten bananas and some citrus, light in tone but sharp in attack. It also smells a little sweet and vanilla-like, with vague florals, apple cider, molasses, dates, peaches and dates, with the slightest rtang of burnt rubber coiling around the back there somewhere. But it sears more than caresses and it’s clear that this is not a lovingly aged product of any kind.

I make this last observation because of its unrefined nature. Even at standard strength, it noses rather raw and jagged, even harsh. There are initial aromas of light glue, rotten bananas and some citrus, light in tone but sharp in attack. It also smells a little sweet and vanilla-like, with vague florals, apple cider, molasses, dates, peaches and dates, with the slightest rtang of burnt rubber coiling around the back there somewhere. But it sears more than caresses and it’s clear that this is not a lovingly aged product of any kind.

Rumaniacs Review #091 | 0598

Rumaniacs Review #091 | 0598