Introduction

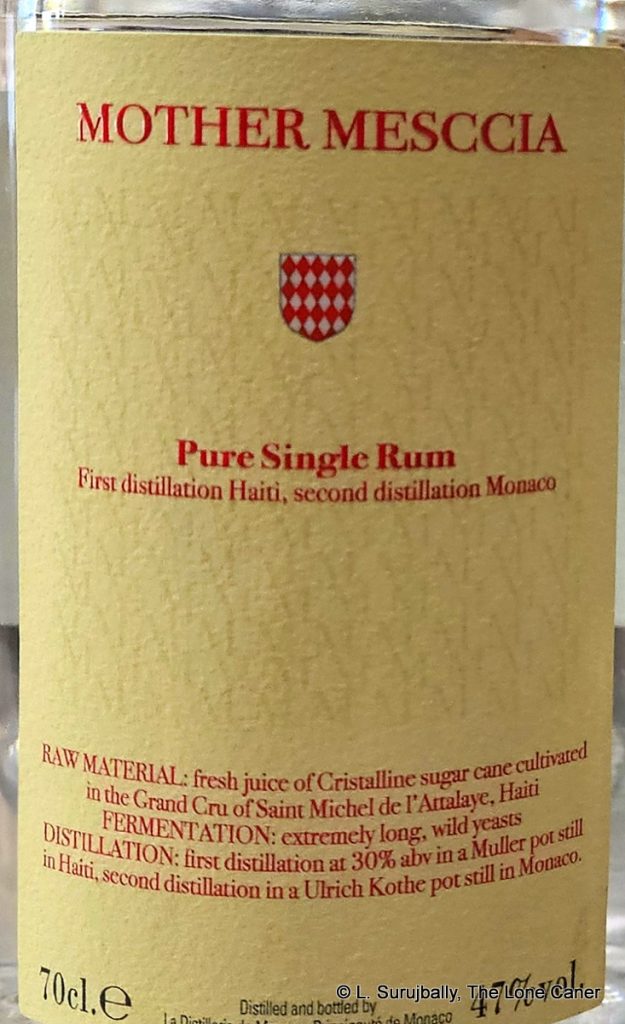

With respect to Velier’s 2025 released white rum called “Mother Mesccia”, it seems to be something of an adapted revival – it’s neither precisely old, nor precisely new. At best, it’s a re-interpretation of a product of yesteryear. But it is interesting, from a historical perspective if nothing else.

The way the story goes, back in the 17th century, Monaco – then a Mediterranean trading hub – often bought rum from Genoese sailors returning from the Caribbean, (they exchanged it for local citrus fruits to ward off the vitamin-C deficiency known as scurvy). This rum was then blended with two fortified wine types: Italian vermouth (a botanicals-infused product) and Sicilian Marsala, and the resultant called mesccia, or mixture. It seems to predate the rum verschnitt of northern Germany, and is coexistent with the traditional eastern European spirits (and “rooms”) that often add flavouring agents to base alcohol. Gradually, the practise of making mesccia faded as Monaco ceased being a major trading port and shifted its economic emphasis to tourism and gambling in the mid 1800s. Still, mesccia was seen, in the Principality if nowhere else, as something of a local institution, and was never entirely forgotten.

In the early 2000s, Prince Albert II of Monaco wanted to revive the practise, but after a few initial attempts failed for quality and other issues, he consulted with Luca Gargano, who runs Velier. Perhaps the choice was logical – Monaco has been ruled by the Genoese-originating Grimaldi family since the 12th century, there was always much trade between the two states, so there’s that connection; and given the historical nature of the project, you can see why the concept would appeal to Luca. He is, after all, known for reimagining spirits-making ideas that predate today’s commercialized mass-market industrial products, and for pushing rum in new directions based on older, more rural traditions.

The rum is made from Haitian crystalline sugar cane grown, crushed and fermented on Michel Sajous’s place at Saint-Michel-de-l’Attalaye, and run through his 380-liter Mueller pot still, resulting in a first run distillate of about 22-34% ABV. This is then shipped in drums to Monaco, where it is distilled a second time to 47% in a Khote hybrid still at L’Orangerie / Distillerie de Monaco. This is a distillery – apparently the only one in the Principality – founded in 2017; it makes mostly gin, botanicals and orange liqueurs, and its master distiller, Philip Colazzo, follows artisanal production methods, something else you just know would appeal to Luca.

That said, it’s important to understand three things.

One, the cutting of the heads and tails is done in Monaco, which some regard as one of the main reasons the final product can be considered as being produced in the Principality (by virtue of its creativity and the needed skillset). The point is, to my mind, debatable — and if anything, muddies the water as to where a rum can truly be said to originate even more.

Secondly, in today’s regulated climate, to reproduce the original recipe of Mesccia cannot be done while still naming the final product a rum. Velier got around this by ageing the final product in ex-Marsala and ex-vermouth wine barrels. It is, as such, its own product, and even Luca admits that it’s not a completely faithful recreation of the way it once was made.

Thirdly, the specific rum we’re looking at today is not aged. The notes above refer to the process that will be instituted for rums to be released in the future, and so this is the base, origin product, the first run distillate – which is why calling it the “Mother Mesccia” is actually completely accurate. One wonders if subsequent releases will be called “sons” or “daughters”, though maybe that’s just my obscure sense of humour at work.

In fine, what we have is a double distilled, unaged, Haitian clairin-type rum, irrespective of where the distillation took place, bottled at 47%.

Certainly it has a Sajous kind of cane-juice vibe, and I remember my first encounter with it with good memories. Much of the character of that the Sajous clairins have always displayed remains: it has initial scents of grass, paper, glue, wax and sawdust, to which are then added some tawny sweet notes of coconut shavings, papaya, melons, cherries, and watermelon rind. There is also a briny note to it all, olives and raw honey dropping from the comb, with the whole aroma being earthy, sweet, salty and surprisingly dry.

Much of this also translates on to the plate, where the 47% dials down the ferociousness that some clairins love to display. Again, it tastes sweetish, grassy, green and there are initially florals and pears and guavas all over the place Yes, it remains briny, even if the olives start to recede a bit, and there’s a nice, if faint, pickled cabbage note there that I quite liked, plus just a trace of vanilla and sugar water. It’s a touch sharp, yet I argue that’s too its benefit – too smooth would destroy some of the aggro that such rums have always displayed, and if we wanted light and smooth, well, there’s always the Bacardi Superior, right? The finish is easy enough, a little hot, sweet, briny, and displaying a last fgine citrus note for edge that closes off the experience quite well.

Thoughts

As a product trying to muscle into an ever more crowded rum space, I think we should regard it as something of an experimental shot across the bows, issued to see what comes out of this bold idea and what the interest is, while the barrels age and the result is examined over the next years. It’s too early to tell where the line will land.

But as a rum in and of itself, I’m somewhat conflicted. It lacks the elemental punch and power of a true 100% Haitian clairin, or the elegant smoothness of a well made rhum agricole like, oh Neisson or Saint James. Its closest analogue outside of Haiti might actually be Saint James’s pot still Coeur de Chauffe, and that’s a compliment, believe me.

So, it is a decent enough rum in its own right, and I liked it, which is why I assign the score that I do. I just fail to see where this is going, or why, outside the ambitions of Monaco’s leader, or the enthusiasm of one of the world’s premiere rum educators, to make it at all. But outside my personal opinion, which I will treat separately (see below), I must admit to being enthused and interested and intrigued, all at once, and I respect Velier’s rum chops enormously – and on that basis, I think that it’s a rum that should be tried, for sure; and watched in the years to come, to see where it goes.

(#1138)(85/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other notes

- Video recap link

- 88 Bamboo did a nice write up of it

- Some news articles regarding the rum and its backstory here and here.

- Velier’s own product page, here.

Opinion

In my personal notes jotted down as I was trying it and listening to the backstory, I commented that I didn’t “get it”. That has nothing to do with the profile, which is just fine, but more based on my wondering why Velier went through all this admittedly fascinating trouble, to make a rum that is difficult to place precisely in the canon.

Something like the much remarked on still-on-a-boat idea, it’s just unclear to me why all this effort is being made. The double-country-distillation makes it neither fish nor fowl, but a brand new product about which we don’t know what to think. Is it a clairin? A European rum? A new blend? How does one even classify such a product? How does it fit within the ongoing debate of where a rum is from? Why was it issued – was it truly just a desire to create a branded, almost defunct Monaco spirit? And was that Luca’s motive for agreeing to be involved? I wonder.

Because you see, when one considers the clear directions and themes of Velier’s other famed releases – Demeraras, Caronis, Clairins, Indian Ocean, Hampdens, Foursquare collaborations, Nine Leaves, the HV pot still examinations – with these you can see a sure hand at the tiller, a sense of single minded focus that leaves little room for doubt. They each examined one type or class of rum and did it damned well, which is why they have the reputation they do.

Yes we did have one-off releases like the Damoiseau 1980, or the MMW/EMB Monymusks and STCE/VR/TECA and TECC Longponds – yet even there, I argue that they had a point they all wanted to make, and that’s what I feel is missing here. Like the flag series of rums done with LM&V, or the Magnums – which, for all their beauty and quality did not really stretch the rumiverse or introduce something new – it seems to be reaching for purpose, and no, imperfectly recreating a historical spirit (or re-imagining one) doesn’t really strike me as good enough. Any standard agricole does about as well, and it’s insufficiently crazy to make me run out and buy a few extra bottles. I’d buy it because it’s Velier, and because it really is quite good, but the doubt remains.