Great nose. Taste and finish don’t quite measure up.

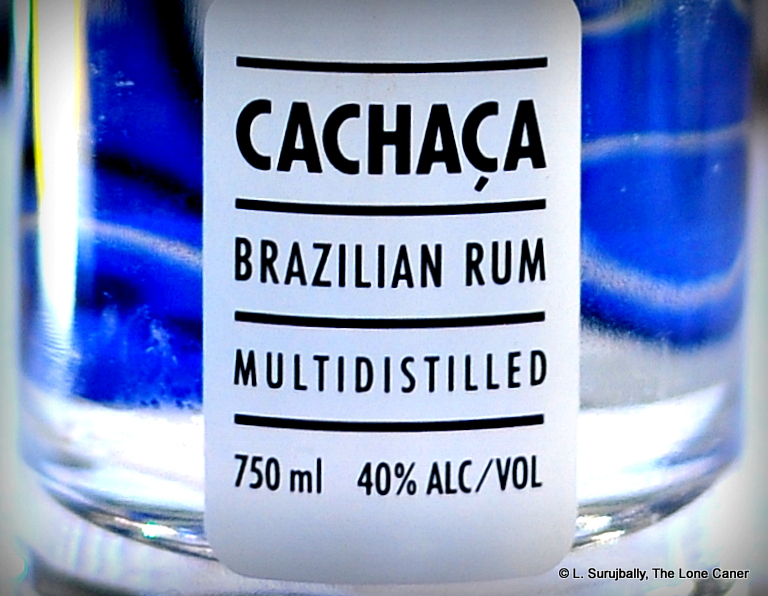

This was a cachaça I bought back in 2011 or thereabouts, and never bothered to open and review because I had zero experience with the spirit beyond getting smacked on caipirinhas a few times; I lacked sufficient background to rate it properly and it seemed to be unfair to score it when there were no fitting comparators. Several years on, nearly three hundred reviews and quite a few Brazilian spirits later, plus available comparators and controls, and I felt better equipped to write something I can put my name behind.

Sagatiba Pura is produced in the small town of Patrocinio Paulista in the state of São Paolo, Brazil. The company was formed in 2004, and through adroit marketing and what must have been pretty good brand ambassadorship, became one of the first cachaças to be widely exported and known outside its country of origin (it claimed to hold a 90% market share of cachaças in Britain in 2007). It was likely this exposure that caused Campari to buy it in 2011 for $26 million. The company also makes Velha and Preciosa variations, which are aged and brown rhums in their own right, unlike this clear one, which was (and remains as of this writing) the only one of the line to make it to Canada. Too, while the USA appears to have gotten the 38% ABV version introduced back in 2013, mine was 40%.

Sagatiba Pura is produced in the small town of Patrocinio Paulista in the state of São Paolo, Brazil. The company was formed in 2004, and through adroit marketing and what must have been pretty good brand ambassadorship, became one of the first cachaças to be widely exported and known outside its country of origin (it claimed to hold a 90% market share of cachaças in Britain in 2007). It was likely this exposure that caused Campari to buy it in 2011 for $26 million. The company also makes Velha and Preciosa variations, which are aged and brown rhums in their own right, unlike this clear one, which was (and remains as of this writing) the only one of the line to make it to Canada. Too, while the USA appears to have gotten the 38% ABV version introduced back in 2013, mine was 40%.

The clear, multi-distilled, unaged cachaça had a nose that was by far the best of the series I tried that day, and though it came from a column still, did a good imitation of being a pot still product. Rich, briny, waxy and redolent of spanish olives with splash of furniture polish, it also had some hints of woodiness lurking in the background (though of course it had not been aged). What made it shine in my estimation was the way it developed – after standing for a few minutes – and started to provide smells of citrus peel, crushed sugar cane, a sweetish amalgam of cinnamon and nutmeg, and even the light perfume of flowers…a really nice aroma all round, light and clean.

It was too bad that this promise didn’t carry over as to how it tasted. It was spicy, clear, clean and dry, not sweet at all, with (initially) little of the delicate perfume the nose suggested. There was a certain metallic taste to it, a mixture of tobacco and wet campfire ashes, almost mineral-y in nature, sufficiently aggressive to squash the lighter vegetals, wet grass, aromatic cigarillos, sugar water, florals, watermelon and sliced pears which came out (helped by some water). These clashing flavours did not, in my estimation, play well together. Exactly the same notes carried over into the fade, which was short and dry and warm and smooth enough, but still ruined by the ashy and smoky, background, which was far too dominant and all-encompassing for me to appreciate it. There was originality here, no doubt, but no adherence to one taste profile over the other – like gambolling puppies they were all allowed to do pretty much what they pleased, without discipline or imposed order.

It’s curious that the Sagatiba is marketed as some kind of premium top end cachaça – it sure doesn’t taste like one, though it is better than the Leblon I tried alongside it. It’s possible that since the majority of the rum drinking public outside Brazil knows little about the type, or because bartenders who nab a bottle or two of it frothed over its potential, that such claims can be made. As far as I’m concerned, it has a snazzy bottle, clean, clear design philosophy (so it looks real cool), and excellent marketing, which, when all is distilled down to what matters – the taste and how it drinks – just makes me shrug and move it to the mixers shelf, which is probably where it always belonged anyway.

(#288 / 78/100)

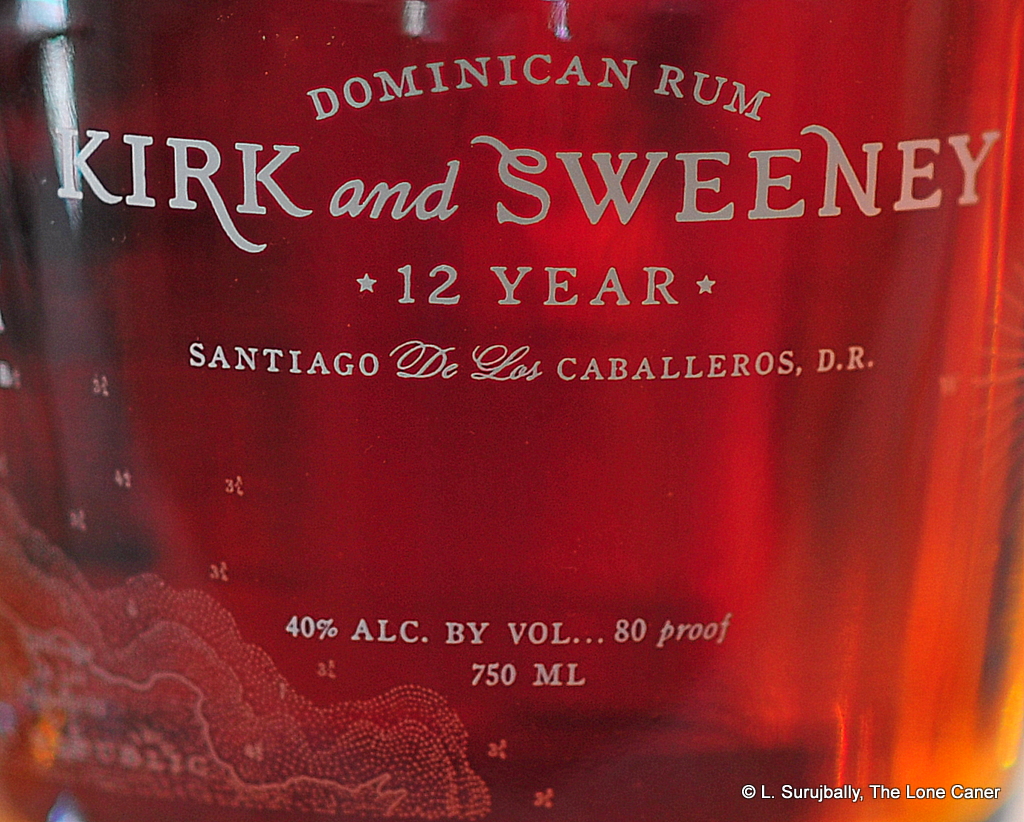

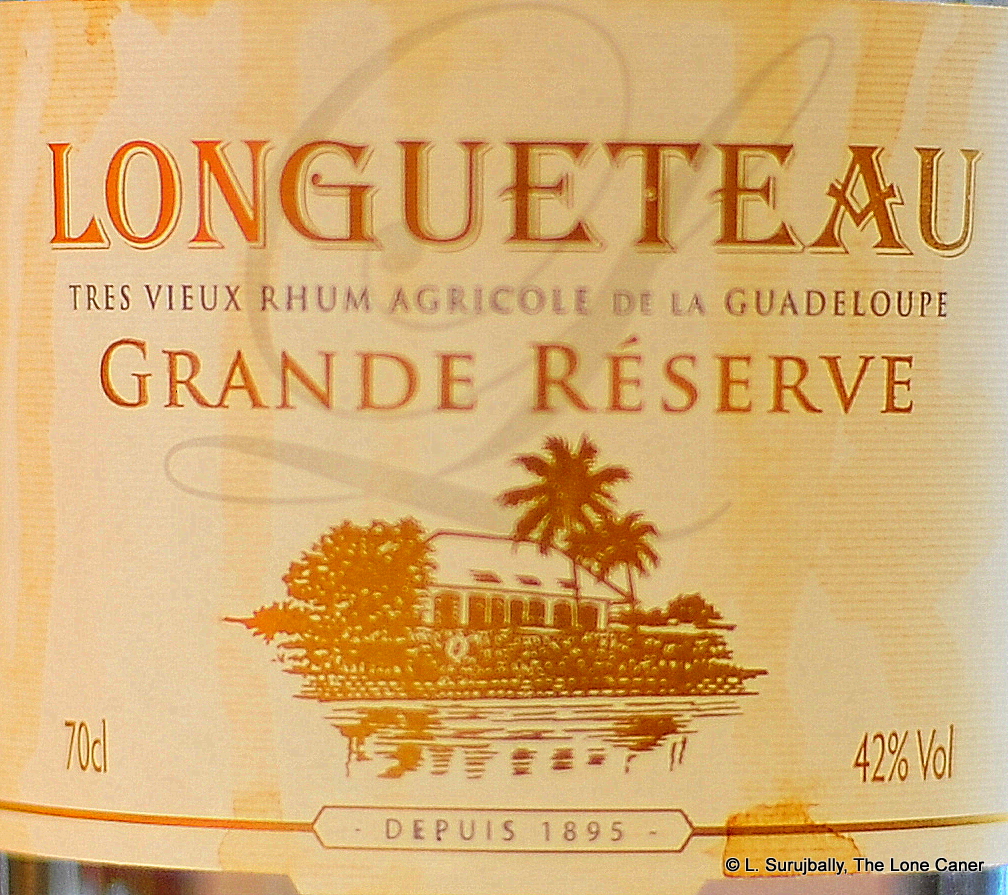

This dark orange-gold ten year old began well on the nose: phenols, acetone, caramel, sweet red licorice, wet cardboard, it gave a good impression of some pot still action going on here, even though it was a column still product. Then there was some fanta or coke — some kind of soda pop at any rate, which I thought odd. Then cherries and citrus zest notes, blooming slowly into black olives, coffee, nuttiness and light vanilla. As a whole, the experience was somewhat easy due to its softness, but overall it was too well constructed for me to dismiss it out of hand as thin or weak.

This dark orange-gold ten year old began well on the nose: phenols, acetone, caramel, sweet red licorice, wet cardboard, it gave a good impression of some pot still action going on here, even though it was a column still product. Then there was some fanta or coke — some kind of soda pop at any rate, which I thought odd. Then cherries and citrus zest notes, blooming slowly into black olives, coffee, nuttiness and light vanilla. As a whole, the experience was somewhat easy due to its softness, but overall it was too well constructed for me to dismiss it out of hand as thin or weak.

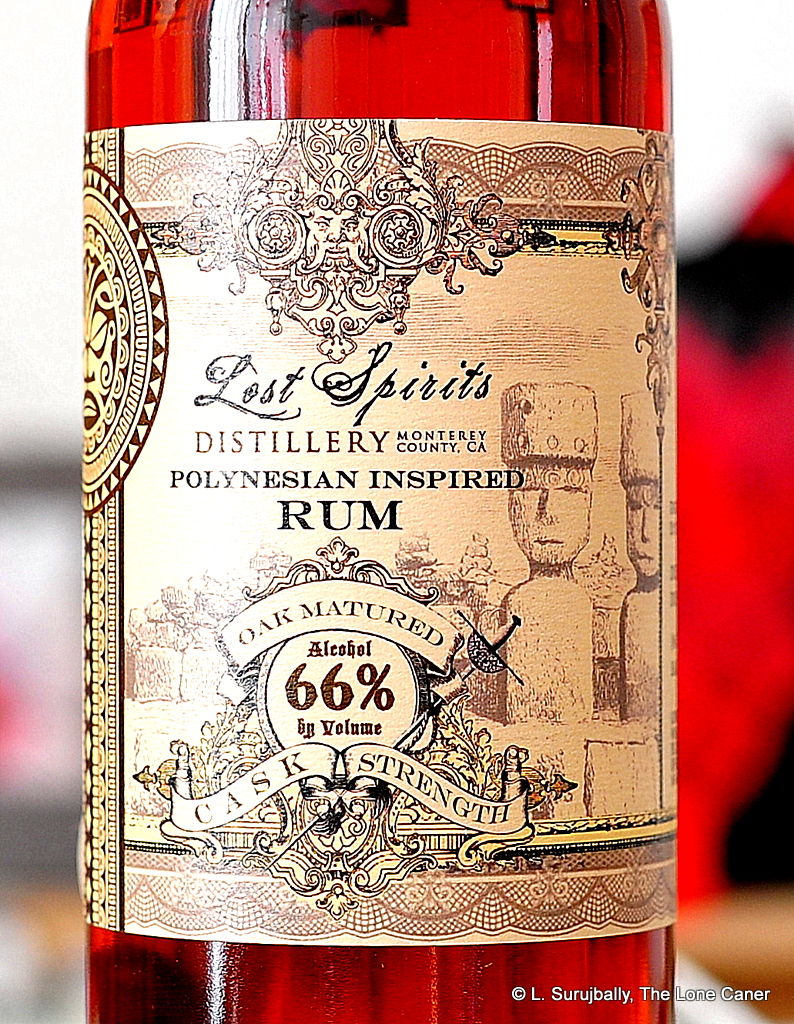

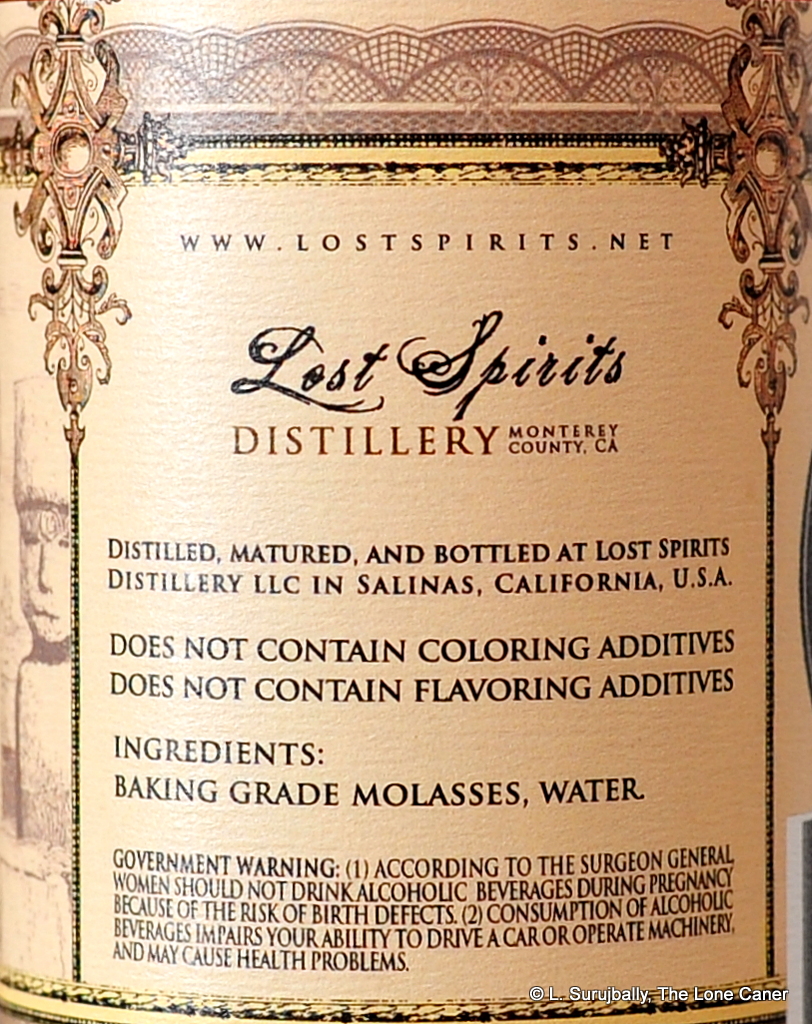

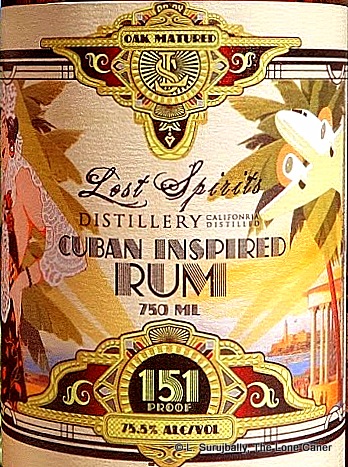

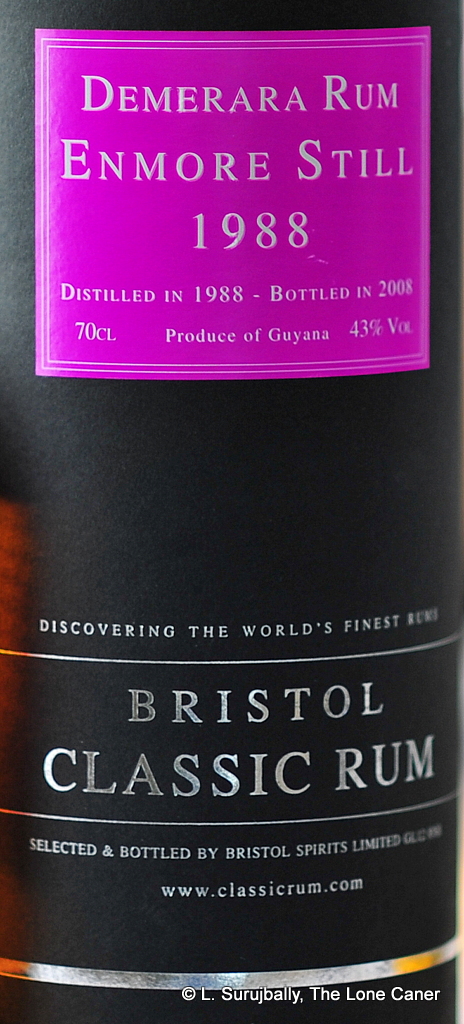

A well made full proof rum should be intense but not savage. The point of the elevated strength is not to hurt you, damage your insides, or give you an opportunity to prove how you rock it in the ‘Hood — but to provide crisper, clearer and stronger tastes that are more distinct (and delicious). When done right, such rums are excellent as both sippers or cocktail ingredients and therein lies much of their attraction for people across the drinking spectrum. Perhaps in the years to come, there’s the potential for rum makers to reach into the past and recreate such a remarkable profile once again. I can hope, I guess.

A well made full proof rum should be intense but not savage. The point of the elevated strength is not to hurt you, damage your insides, or give you an opportunity to prove how you rock it in the ‘Hood — but to provide crisper, clearer and stronger tastes that are more distinct (and delicious). When done right, such rums are excellent as both sippers or cocktail ingredients and therein lies much of their attraction for people across the drinking spectrum. Perhaps in the years to come, there’s the potential for rum makers to reach into the past and recreate such a remarkable profile once again. I can hope, I guess.

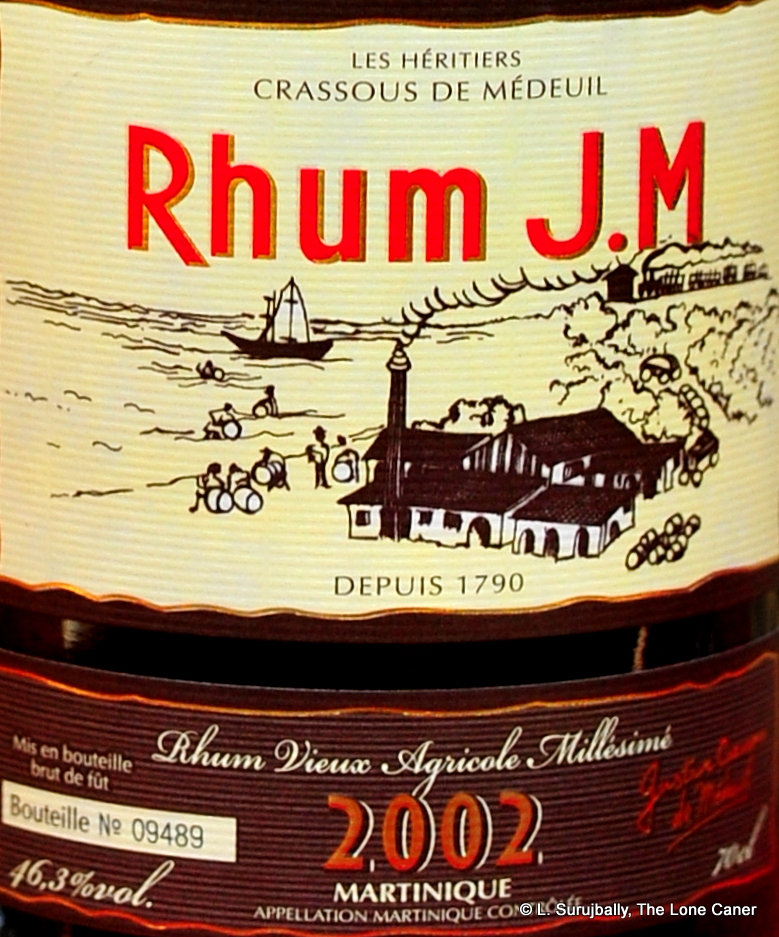

Rumaniacs Review 022 | 0422

Rumaniacs Review 022 | 0422

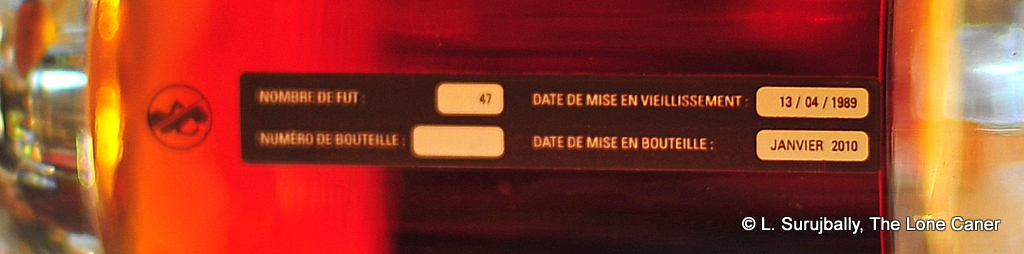

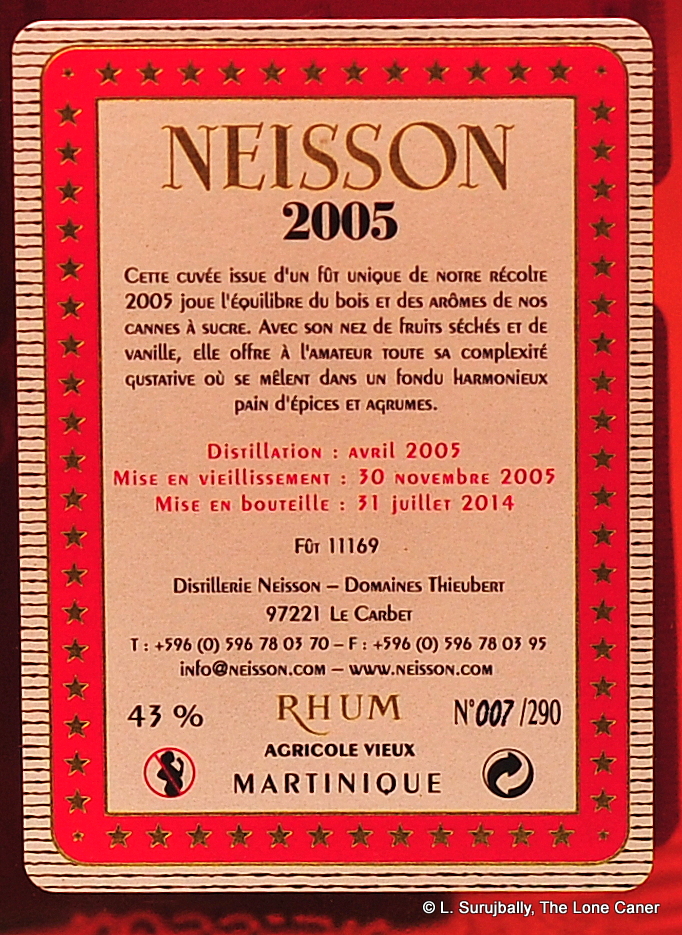

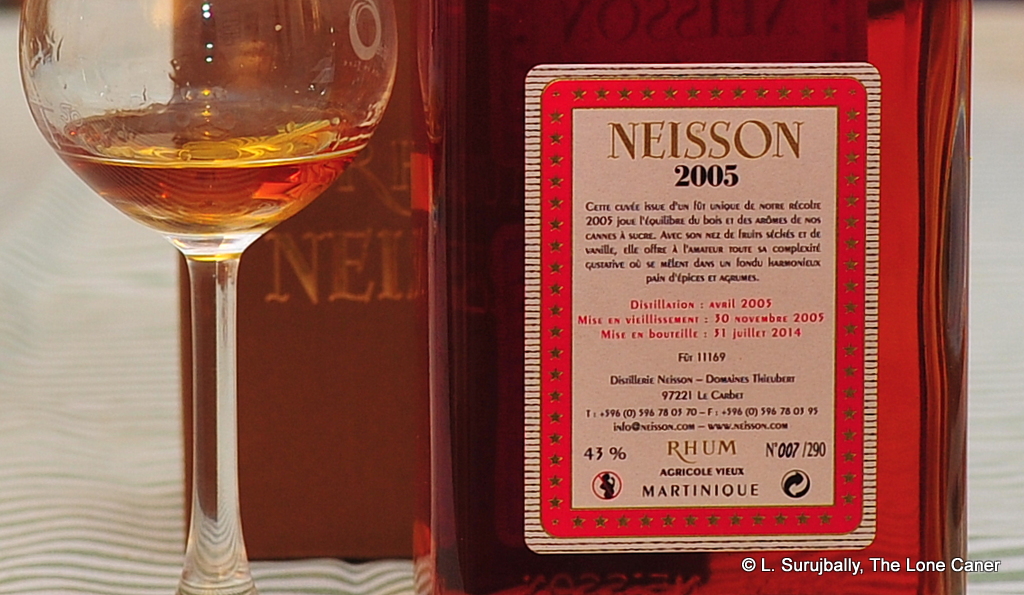

I speak of course of that oily, sweet salt tequila note that I’ve noted on all Neissons so far. What made this one a standout in its own way was the manner in which that portion of the profile was dialled down and restrained on the nose – the 43% made it an easy sniff, rich and warm, redolent of apples, pears,and watermelons…and that was just the beginning. As the rhum opened up, the fleshier fruits came forward (apricots, ripe red cherries, pears, papayas, rosemary, fennel, attar of roses) and I noted with some surprise the way more traditional herbal and grassy sugar cane sap notes really took a backseat – it didn’t make it a bad rhum in any way, just a different one, somewhat at right angles to what one might have expected.

I speak of course of that oily, sweet salt tequila note that I’ve noted on all Neissons so far. What made this one a standout in its own way was the manner in which that portion of the profile was dialled down and restrained on the nose – the 43% made it an easy sniff, rich and warm, redolent of apples, pears,and watermelons…and that was just the beginning. As the rhum opened up, the fleshier fruits came forward (apricots, ripe red cherries, pears, papayas, rosemary, fennel, attar of roses) and I noted with some surprise the way more traditional herbal and grassy sugar cane sap notes really took a backseat – it didn’t make it a bad rhum in any way, just a different one, somewhat at right angles to what one might have expected. But I also didn’t get much in the way of wonder, of amazement, of excitement…something that would enthuse me so much that I couldn’t wait to write this and share my discovery. That doesn’t make it a bad rhum at all (as stated, I thought it was damned good on its own merits, and my score reflects that)…on the other hand, it hardly makes you drop the wife off to her favourite sale and rush out to the nearest shop, now, does it?

But I also didn’t get much in the way of wonder, of amazement, of excitement…something that would enthuse me so much that I couldn’t wait to write this and share my discovery. That doesn’t make it a bad rhum at all (as stated, I thought it was damned good on its own merits, and my score reflects that)…on the other hand, it hardly makes you drop the wife off to her favourite sale and rush out to the nearest shop, now, does it?