After having written on and off about Yoshiharu Takeuchi’s company Nine Leaves for many years, and watching his reputation and influence grow, it seems almost superfluous to go on about his background in any kind of detail. However, for those new to the company who want to know what the big deal is, it’s a one-man rum-making outfit located in Japan, and Yoshi-san remains its only employee (at least until July 2020, when he takes on an apprentice, so I am reliably informed).

Nine Leaves has been producing three kinds of pot-still rums for some time now: six month old rums aged in either French oak or ex-bourbon, and slightly more aged expressions up to two years old with which Yoshi messes around….sherry or other finishes, that kind of thing. The decision to keep things young and not go to five, eight, ten years’ ageing, is not entirely one of preference, but because the tax laws of Japan make it advisable, and Yoshi-san has often told me he has no plans to go in the direction of double digit aged rums anytime soon…though I remain hopeful. I’ve never really kept up with all of his work – when there’s at least four rums a year coming out with just minor variations, it’s easy to lose focus – but neither have I left it behind. His rums are too good for that. He’s a perennial stop for me in any rumfest where he and I intersect.

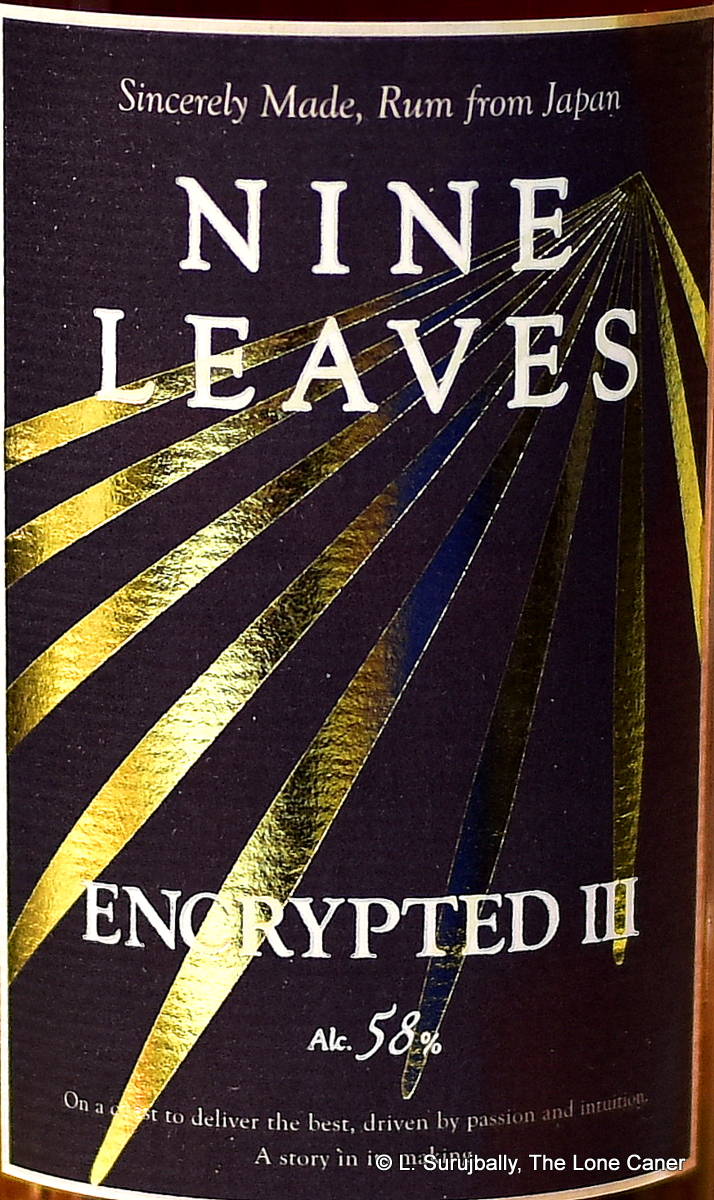

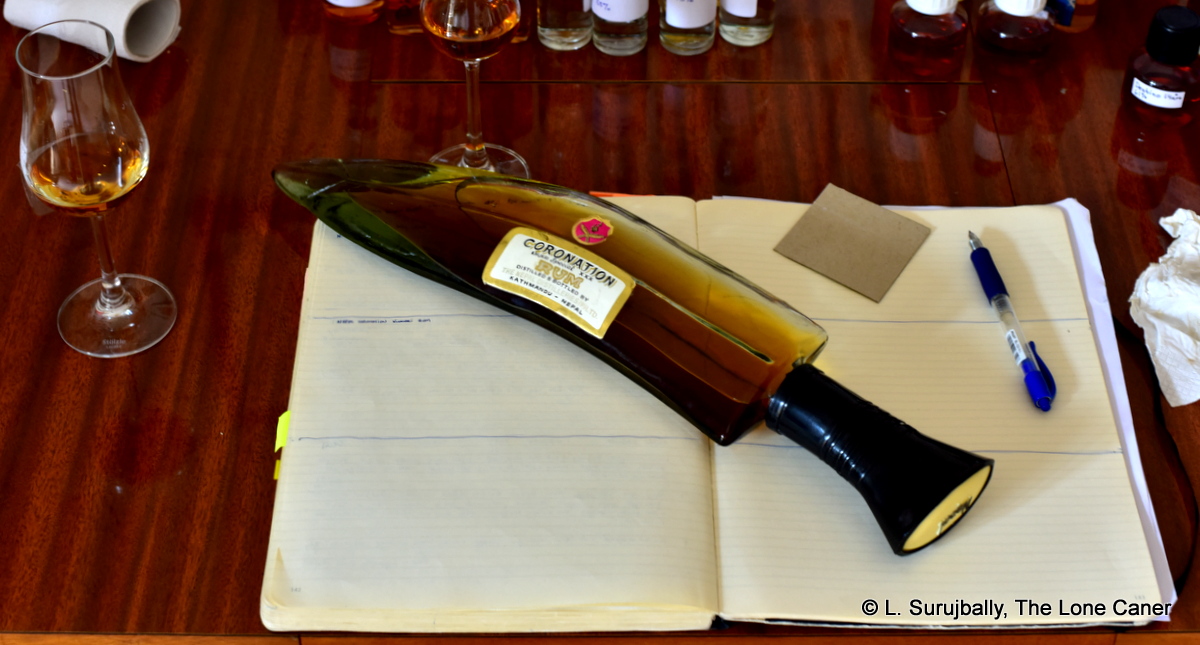

But now, here is the third in his series of Encrypted rums (Velier’s 70th Anniversary Edition from Nine Leaves was humorously referred to as “Encrypted 2½“) and is an interesting assembly: a blend six different Nine Leaves rums, the youngest of which is two years old. The construction is nowhere mentioned on the elegantly spare label (probably for lack of space) but it’s composed of rums aged or finished in in two different types of P/X barrels, in bourbon barrels, Cabernet Sauvignon barrels, Chardonnay barrels….and one more, unmentioned, unstated. And in spite of insistent begging, occasional threats, offers of adoption, even promises to be his third employee, Yoshi-san would not budge, and secret that sixth rum remains.

Whatever the assembly, the results spoke for themselves – this thing was good. Coming on the scene as the tide of the standard strength forty percenters was starting to ebb, Nine Leaves has consistently gone over 40% ABVm mostly ten points higher, but this thing was 58% so the solidity of its aromas was serious. It was amazingly rich and deep, and presented initially as briny, with olives, vegetable soup and avocados. The fruity stuff came right along behind that – plums, grapes, very ripe apples and dark cherries, and then dill, rye bread, and a fresh brie. I also noticed some sweet stuff sweet like nougat and almonds, cinnamon, molasses, and a nice twitch of citrus for a touch of edge. To be honest, I was not a little dumbfounded, because it was outside my common experience to smell this much, stuffed into a rum so young.

The rum is coloured gold and is in its aggregate not very old, but it has an interesting depth of texture and layered taste that could surely not be bettered by rums many times its age. Initially very hot, once it dialled into its preferred coordinates, it tasted both fruity and salty at the same time, something like a Hawaiian pizza, though with restrained pineapples (which is a good thing, really). Initially there were tastes of plums and dark fruits like raisins and prunes and blackberries, mixed up with molasses and salted caramel ice cream. These gradually receded and ceded the floor to a sort of salty, minerally, tawny amalgam of a parsley-rich miso soup into which some sour cream has been dropped and delicate spices – vanilla, cinnamon, a dust of nutmeg and basil. I particularly enjoyed the brown, musky sense of it all, which continued right into a long finish that not only had that same sweet-salt background, but managed to remind me of parched red earth long awaiting rain, and the scent of the first drops hissing and steaming off it.

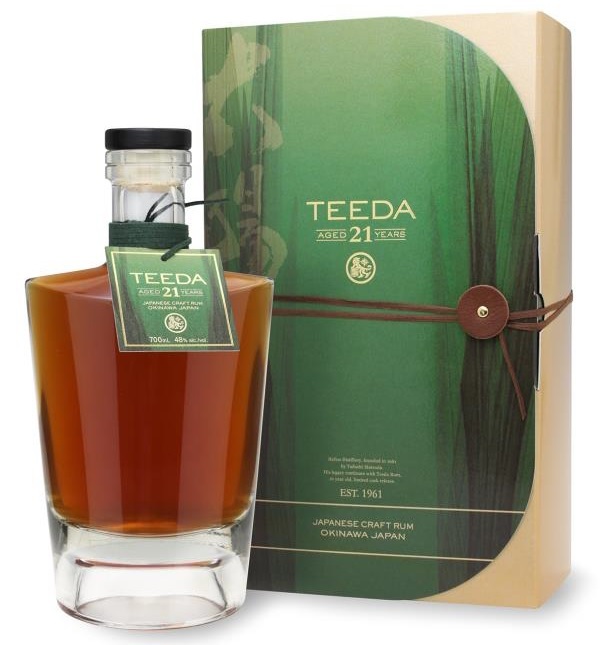

I have now tasted this rum three times, and my initially high opinion of it has been confirmed on each subsequent occasion. The “Encrypted” series just gets better every time, and the sheer complexity of what’s in there is stunning for a rum that young, making a strong case that blending can produce a product every bit as good as any pure single rum out there, and it’s not just Foursquare that can do it. I think it handily eclipses anything else made in Japan right now, except perhaps the 21 year old “Teeda” from Helios which is both weaker and older. But the comparison just highlights the achievement of this one, and it is my belief that even if I don’t know what the hell that sixth portion in the blend is, the final product stands as one of the best Nine Leaves has made to date, and a formidable addition to the cabinet of anyone who knows and loves really good rum.

(#743)(88/100)

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages (

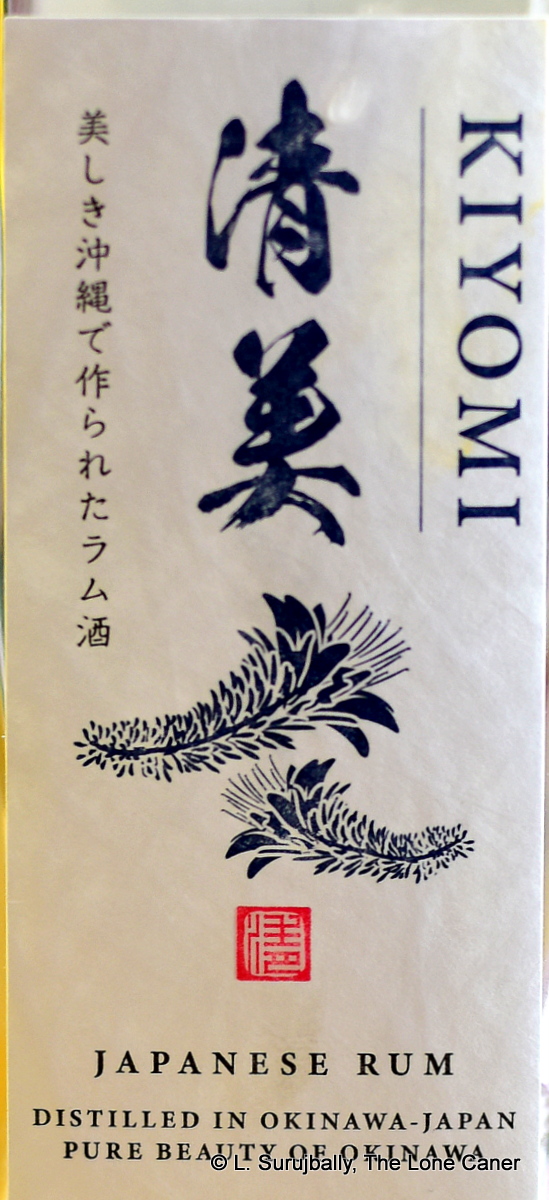

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages ( The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

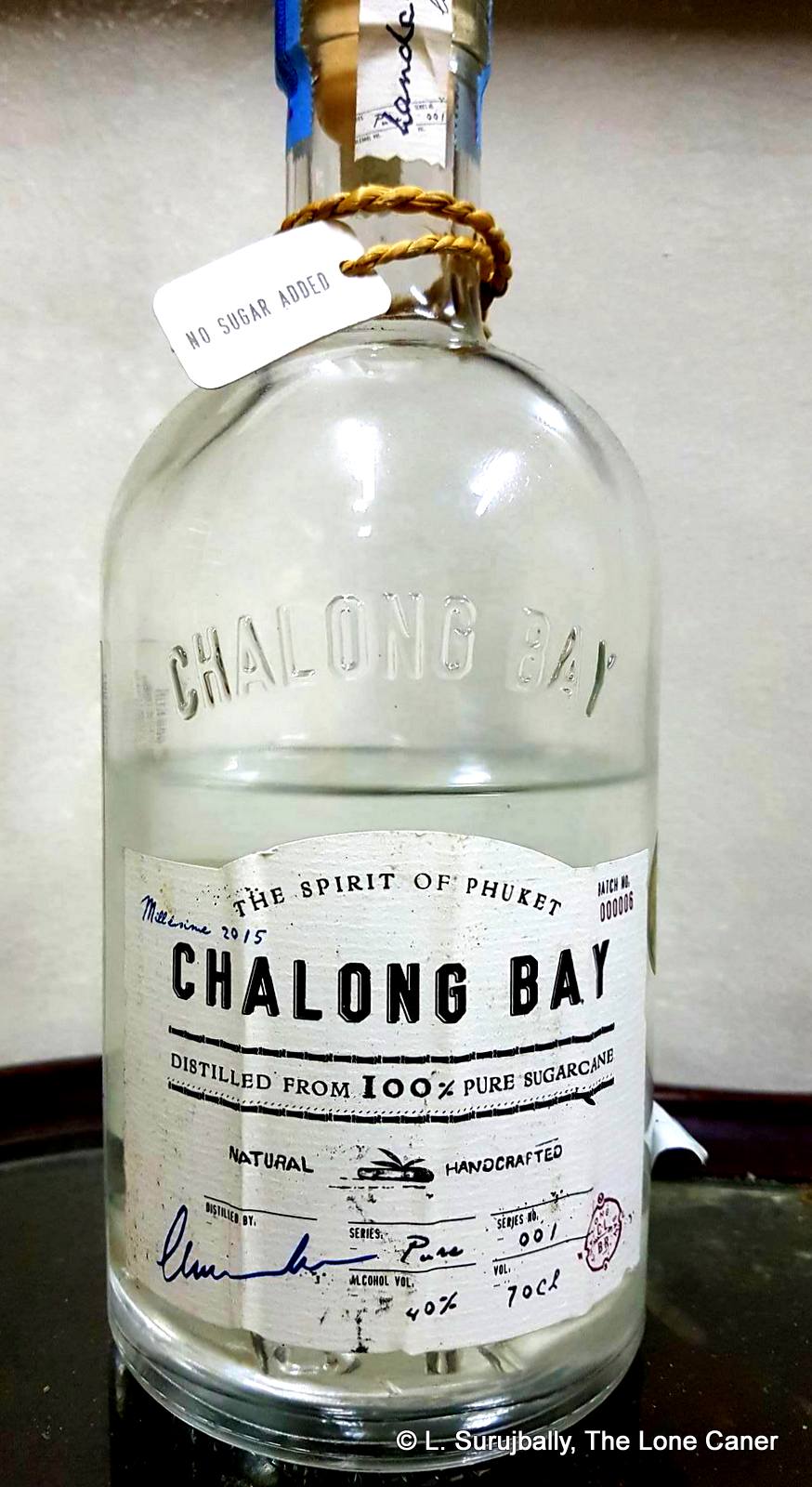

I’ve never been completely clear as to what effect a resting period in neutral-impact tanks would actually have on a rum – perhaps smoothen it out a bit and take the edge off the rough and sharp straight-off-the-still heart cuts. What is clear is that here, both the time and the reduction gentle the spirit down without completely losing what makes an unaged white worth checking out. Take the nose: it was relatively mild at 40%, but retained a brief memory of its original ferocity, reeking of wet soot, iodine, brine, black olives and cornbread. A few additional nosings spread out over time reveal more delicate notes of thyme, mint, cinnamon mingling nicely with a background of sugar water, sliced cucumbers in salt and vinegar, and watermelon juice. It sure started like it was out to lunch, but developed very nicely over time, and the initial sniff should not make one throw it out just because it seems a bit off.

I’ve never been completely clear as to what effect a resting period in neutral-impact tanks would actually have on a rum – perhaps smoothen it out a bit and take the edge off the rough and sharp straight-off-the-still heart cuts. What is clear is that here, both the time and the reduction gentle the spirit down without completely losing what makes an unaged white worth checking out. Take the nose: it was relatively mild at 40%, but retained a brief memory of its original ferocity, reeking of wet soot, iodine, brine, black olives and cornbread. A few additional nosings spread out over time reveal more delicate notes of thyme, mint, cinnamon mingling nicely with a background of sugar water, sliced cucumbers in salt and vinegar, and watermelon juice. It sure started like it was out to lunch, but developed very nicely over time, and the initial sniff should not make one throw it out just because it seems a bit off.

Consider first the nose of this

Consider first the nose of this

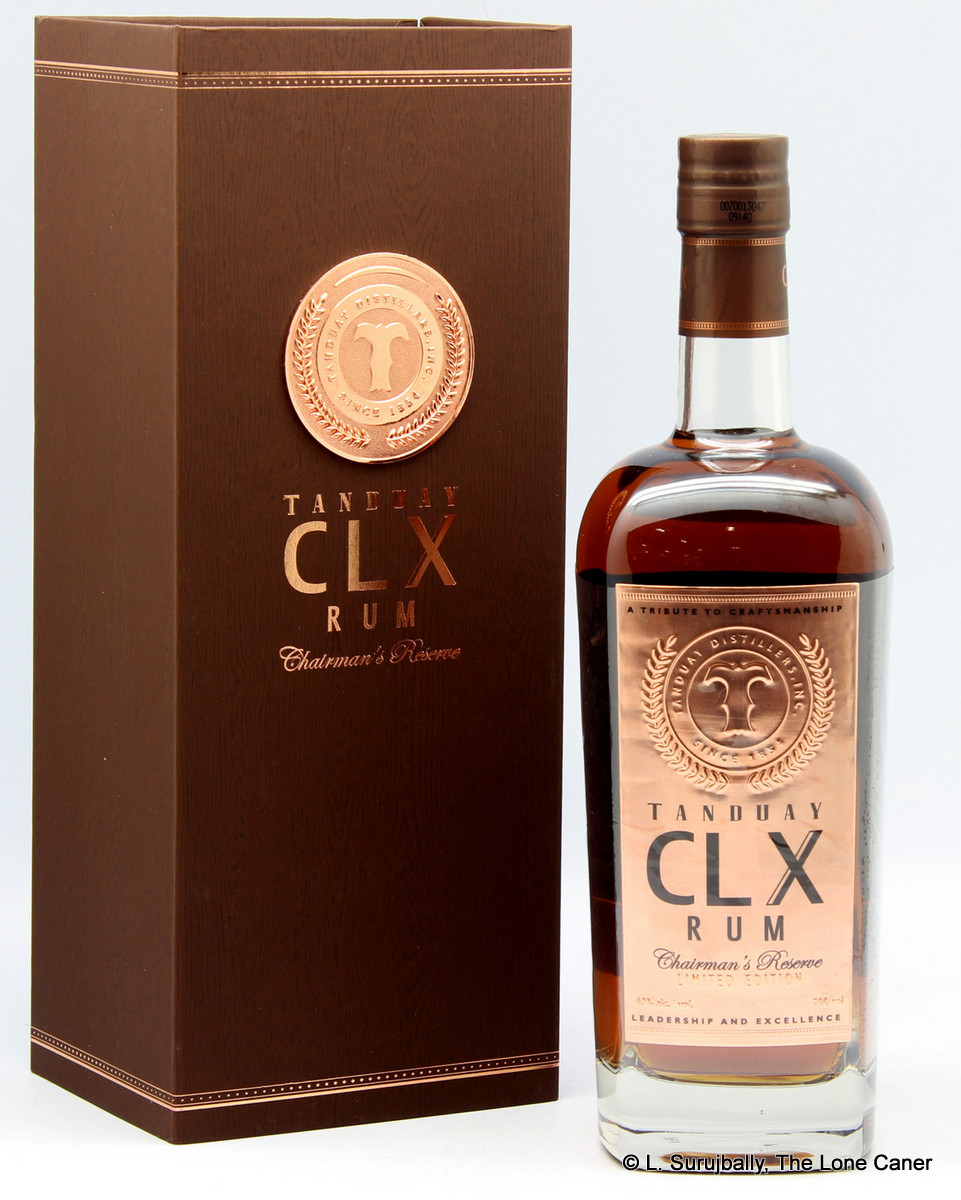

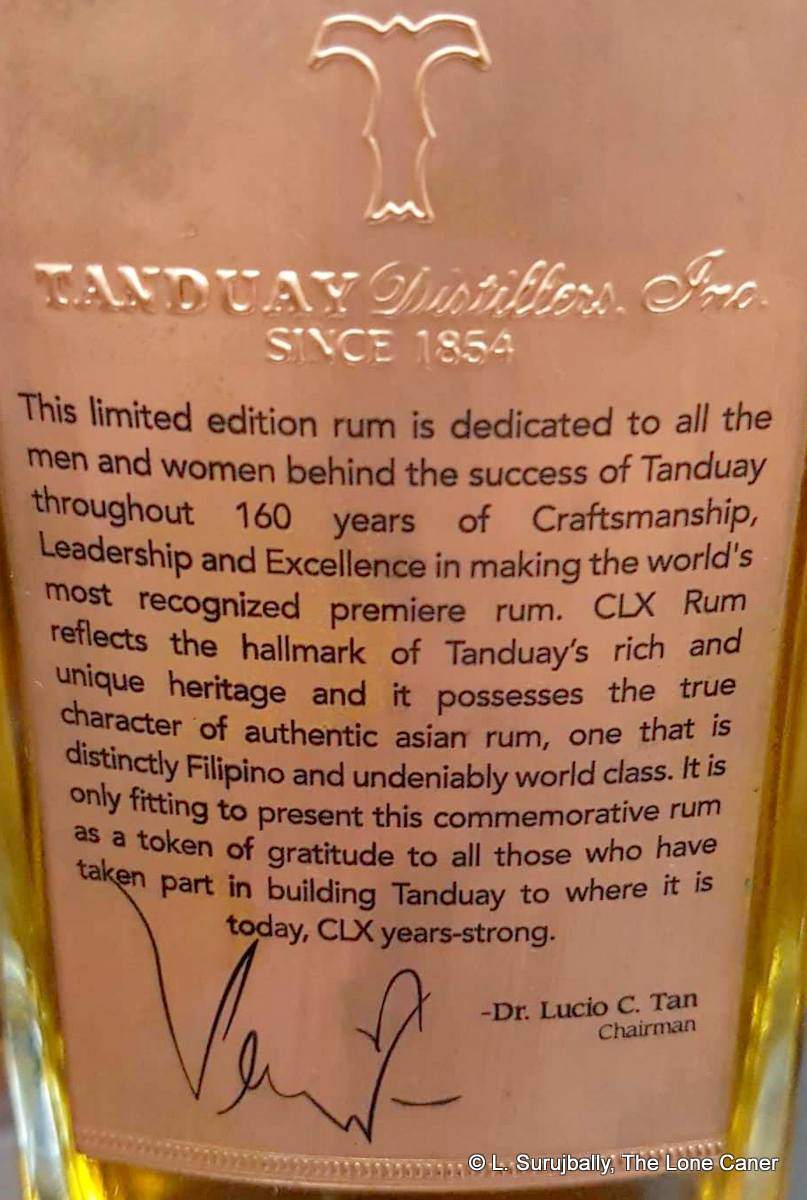

Anyway, when we’re done with do all the contorted company panegyrics and get down to the actual business of trying it, do all the frothy statements of how special it is translate into a really groundbreaking rum?

Anyway, when we’re done with do all the contorted company panegyrics and get down to the actual business of trying it, do all the frothy statements of how special it is translate into a really groundbreaking rum?  Like most rums of this kind, the opinions and comments are all over the map. Some are savagely disparaging, other more tolerant and some are almost nostalgic, conflating the rum with all the positive experiences they had in Thailand, where the rum is made. Few have had it in the west, and those that did weren’t writing much outside travel blogs and review aggregating sites.

Like most rums of this kind, the opinions and comments are all over the map. Some are savagely disparaging, other more tolerant and some are almost nostalgic, conflating the rum with all the positive experiences they had in Thailand, where the rum is made. Few have had it in the west, and those that did weren’t writing much outside travel blogs and review aggregating sites.

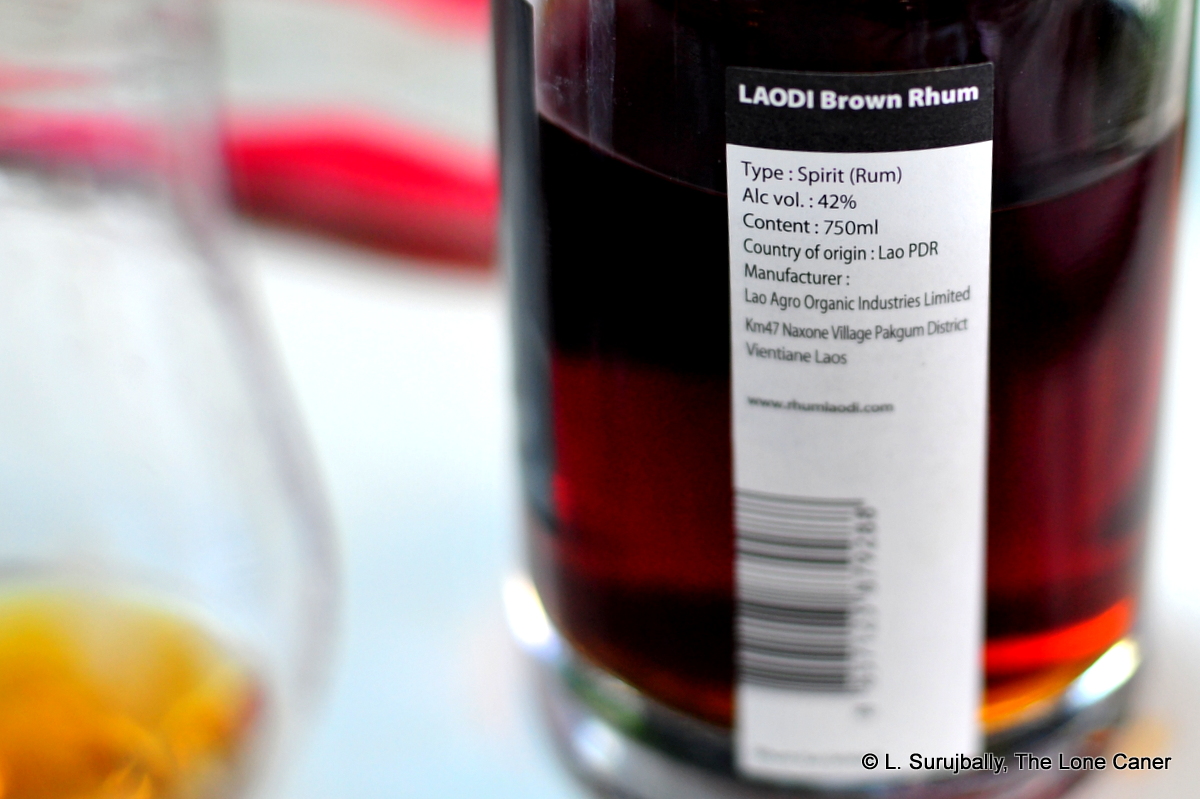

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything.

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything. Now here’s an interesting standard-proofed gold rum I knew too little about from a country known mostly for the spectacular temples of Angor Wat and the 1970s genocide. But how many of us are aware that Cambodia was once a part of the Khmer Empire, one of the largest in South East Asia, covering much of the modern-day territories of Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Viet Nam, or that it was once a protectorate of France, or that it is known in the east as Kampuchea?

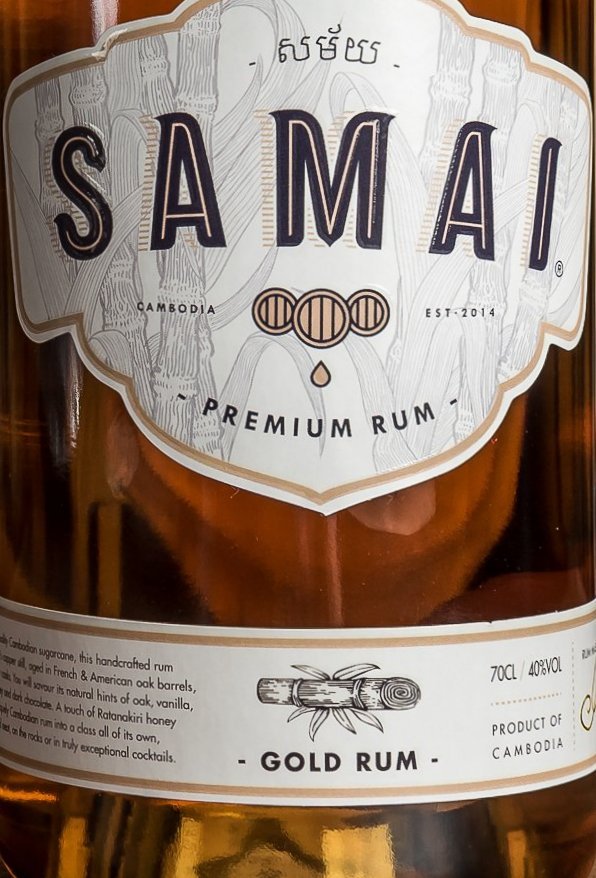

Now here’s an interesting standard-proofed gold rum I knew too little about from a country known mostly for the spectacular temples of Angor Wat and the 1970s genocide. But how many of us are aware that Cambodia was once a part of the Khmer Empire, one of the largest in South East Asia, covering much of the modern-day territories of Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Viet Nam, or that it was once a protectorate of France, or that it is known in the east as Kampuchea? Thailand doesn’t loom very large in the eyes of the mostly west-facing rum writers’ brigade, but just because they make it for the Asian palate and not the Euro-American cask-loving rum chums, doesn’t mean what they make can be ignored; similar in some respects to the light rums from Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Panama and Latin America, they may not be rums

Thailand doesn’t loom very large in the eyes of the mostly west-facing rum writers’ brigade, but just because they make it for the Asian palate and not the Euro-American cask-loving rum chums, doesn’t mean what they make can be ignored; similar in some respects to the light rums from Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Panama and Latin America, they may not be rums