The most searingly powerful rum you are ever likely to try. Do not simultaneously bloviate and drink this, or spontaneous combustion may occur.

(#119. 81/100) [Video Review]

Don’t be frightened. A rum like the Scotch Malt Whisky Society’s R5.1 Longpond 9 year old, bottled at a grinningly ferocious cask-strength 81.3%, isn’t really out there to kill you: it just feels that way. I used to laugh at the way Bacardi 151 and Appleton 151 made wussie forty percenters run a hot chocolate delivery into their pants…well, here’s one that takes it a step further and indulges itself in a level of industrial overkill and outright belligerence one can only admire. It’s a Longpond, it’s cask strength, its over 160 proof of tail-whuppin’ badass. Tread warily, because it smells your fear.

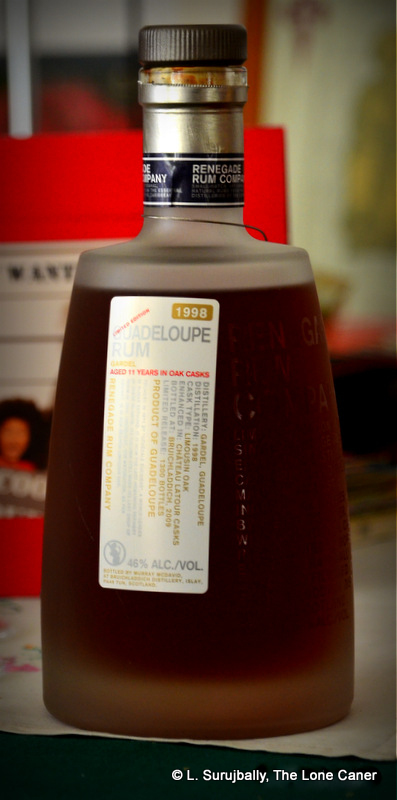

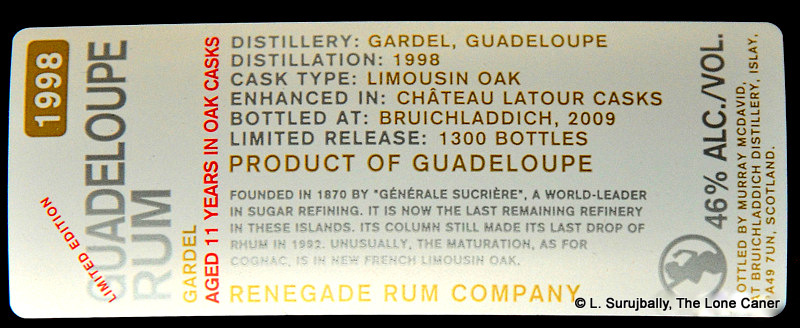

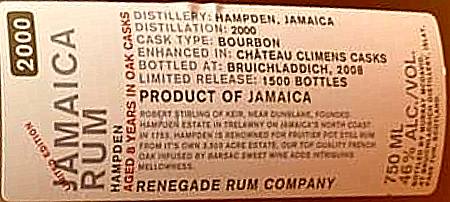

For rummies out there who, like me on occasion, are not so much into whisky lore and tend to flip an insouciant bird at the maltsters (for my whisky loving friends reading this, it’s the other guys, not you), it should be noted that the SMWS has a stated philosophy of taking what is in the barrel out of the barrel, and bottling it as is. Bam. Take that. No muckin’ about, no weak-kneed nonsense like “drinking strength” or “dilution with distilled water” – what you had been ageing is what you get (you can just see the boys at the Society politley ignoring the rums of Cadenhead and Renegade). As for the R5.1, much as you might think this is an amped-up Audi supercar, it just means it derives from the first barrel of rum bought, and the 5th distillery from which they have bought it, in this case, Longpond out of Jamaica.

The corked green bottle was marked with the SMWS logo, details of origin, and tasting notes (clicking on the photo above will enlarge it so you can read, if you wish), but since I don’t read others’ tasting notes until I’ve made my own, I just went straight ahead and decanted a hay-blonde spirit into the glass. And here I must warn you that while it smelled fantastically original, you simply could not ignore 162.6 proof – that’s not far away from pure alcohol and the aroma is therefore, a shade nuts. Medicine, grass and freshly turned sod, with strong briny and iodine overtones, yet not so much as to make me suggest peat, more like a weird plasticine some crazy kid wants to play with (note to my friends – I refer to others’ children, not yours).

The arrival was strongly heated, as if Satan’s brimstone-flavoured pitchfork was smoothly stroking my palate. Yet there was a trace of honey and chocolate mints there also, among the medicine and the grass, and while the turpentine evident in the taste suggested a failed artist had breathed on this baby, I have to acknowledge its overall complexity, even if it wasn’t really to my taste – I’ve continually whinged about rum moving above 40%, but 81.3% is simply too much. Maybe regular cask-strength whisky drinkers would drool over this powerful drink more than I would. It does make a cocktail that is simply incredible, mind you.

The arrival was strongly heated, as if Satan’s brimstone-flavoured pitchfork was smoothly stroking my palate. Yet there was a trace of honey and chocolate mints there also, among the medicine and the grass, and while the turpentine evident in the taste suggested a failed artist had breathed on this baby, I have to acknowledge its overall complexity, even if it wasn’t really to my taste – I’ve continually whinged about rum moving above 40%, but 81.3% is simply too much. Maybe regular cask-strength whisky drinkers would drool over this powerful drink more than I would. It does make a cocktail that is simply incredible, mind you.

And I must say this — the finish is, quite simply, awesome: it goes on and on and on like a pornstar on a performance bonus…I’ve never had anything remotely like it. Five minutes after my first swallow, the fumes were still meandering up my throat in what may be the longest finish I’ve ever had, even if it does remind me somewhat of iodine flavoured camphor balls. And then, just when other rums (Lemon Hart 151, Stroh 80 or Bacardi 151) run out of steam, the R5.1 burns hotter, pushes harder, gives more. This experience quickly exhausted my curses in six languages and I was reduced to weakly muttered childish wows and holy cows. Trust me, after several glasses of this monster, your eyes wobble and your sphincter seizes up, and still the rum keeps on coming.

So: the taste is biblical, the arrival is extraordinary, and the finish so strong that if it was more it would be practically nuclear and be banned by all free nations: it’s a tonsil tearing, all-out assault on your sanity. This rum should be issued with not only health advisories, but camo-green (oh wait…). It may not be the best rum you’ve ever had (though it’s probably the strongest you’ll ever try), but you can believe me when I tell you it’s absolutely among the most original.

“If in your travels you see God,” says a modest Hattori Hanzo, the ultimate sword-maker in “Kill Bill,” when the Bride was selecting a katana, “God will be cut.” I like this kind of becoming humility in a craftsman. It’s a kind of reverse arrogance, acknowledging a self-evident mastery so overwhelming, so off the scale, so beyond mere hyperboles like “fantastic” or “zoweee” that there’s actually no need to mention it at all — the product speaks for itself.

The makers of R5.1 Longpond 9 year old fall into this group of such self-deprecating uber-senseis. It’s not that they have made a rum excellent enough that God will smile, help himself to a second roti and curry goat and pour you both another shot, no (although this is not entirely beyond the realms of possibility) – it’s more like they created a concoction so incredibly powerful, so fearsomely, mind-numbingly strong (and good, let’s not forget) that if, in your travels, you did meet God in a beer garden down by de backdam, then trust me…God would get drunk.

Other notes

Yes, there are rums stronger than this one: the 84.5% Sunset Very Strong out of St. Vincent for one. I tasted that one in late 2015 and it’s not half bad…as long as one exercises all the usual cautions. Oh and there’s the Marienburg 90% from Suriname, which is stronger in proof but weaker in quality than both. In 2020 I finally listed the 21 strongest rums in the world in an article of their own,