#307

Inhaling the powerful scents of this rhum is to be reminded of all the reasons why white unaged agricoles should be taken seriously as drinks in their own right. Not for Longueteau and La Confrérie the fierce, untamed — almost savage — attack of the clairins; and also not for them the snore-fests of the North American whites which is all that far too many have tried. When analyzing the aromas billowing out from my tasting glass, what I realized was that this thing steered a left-of-middle course between either of those extremes, while tilting more towards the backwoods moonshine style of the former. It certainly presented as a hot salt and wax bomb on initial inspection, one couldn’t get away from that, but it smoothened out and chilled out after a few minutes, and coughed up a few additional notes. Was there some pot still action going on here? Not as far as I know, more a creole column still. It was a briny, creamy, estery, aromatic nose, redolent of nail polish and acetone (which faded) watermelon, cucumbers, swank, a dash of lemon and camomile…and maybe a pimento or two for some kick (naah – just kidding about that last one).

The taste of this thing was excellent: spicy hot, fading to warm, and surprisingly smooth for a rhum where I had expected more intensity. Like many well made full proofs, the integration of the various elements was well done, hardly something we always expect from an unaged white; and after the initial discomfort one hardly noticed that it was a 50% rhum at all. It was comparatively light too, another point of divergence from expectations. It tasted of all the usual notes that characterize white agricoles – vegetals, lemongrass, cucumbers and watermelon, more sugar water (it hinted at sweetness without bludgeoning you into a diabetic coma with it) – and then added a few interesting points of its own, such as green thai curry in coconut milk, and (get this!) the musky sweetness of green peas. It all closed up shop with a nicely long-ish, dry-ish, intense and almost elegant finish, with an excellent balance of zest, creamy cheese and those peas, and some of the esters and acetones carrying over from where everything had started. The balance could be better, but I had and have no complaints.

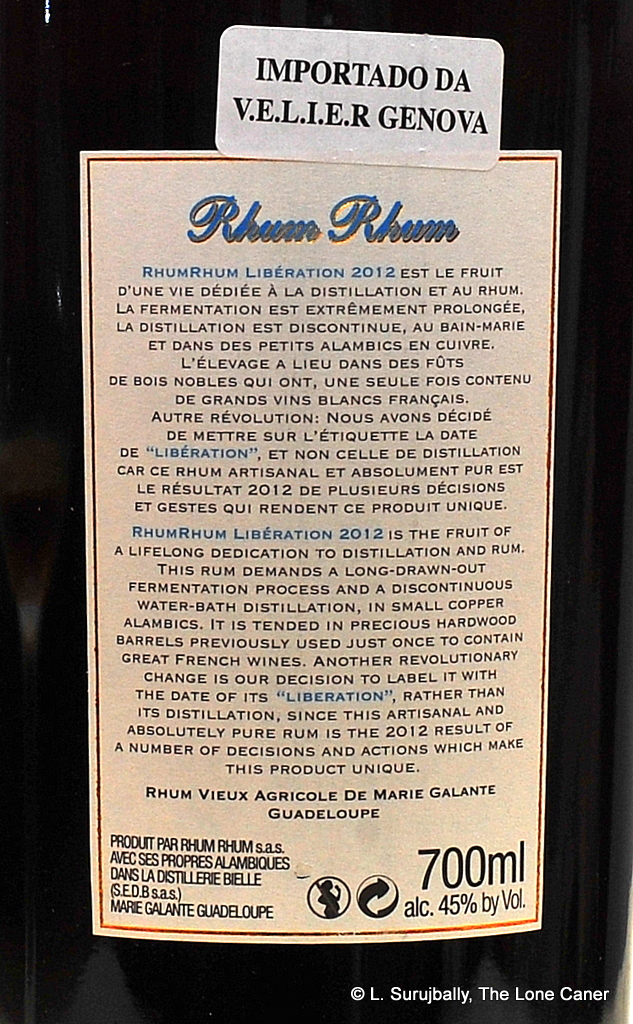

La Confrérie are not independent bottlers in the way Velier, Rum Nation or Compagnie des Indes are. What they do is work in collaboration with a given distillery, and then act more as co-branders than issuers. This provides the distillery with the imprimatur of a small organization well known – in Europe generally and France in particular – for championing and promoting rhum, who have selected the casks carefully; and gives La Confrérie visibility for being associated with the distillery. Note that La Confrérie is also involved in deciding which shops get to sell the rhum, so certainly some economic incentives are at work here. (There are some other background notes on La Confrérie in the HSE 2007 review, if you’re interested). The two co-founders — Benoit Bail and Jerry Gitany – are currently touring Europe on an Agricole Tour to promote and extend the visibility of French island rhums, so their enthusiasm and affection for agricoles is not just a flash in the pan, but something to be taken seriously.

La Confrérie are not independent bottlers in the way Velier, Rum Nation or Compagnie des Indes are. What they do is work in collaboration with a given distillery, and then act more as co-branders than issuers. This provides the distillery with the imprimatur of a small organization well known – in Europe generally and France in particular – for championing and promoting rhum, who have selected the casks carefully; and gives La Confrérie visibility for being associated with the distillery. Note that La Confrérie is also involved in deciding which shops get to sell the rhum, so certainly some economic incentives are at work here. (There are some other background notes on La Confrérie in the HSE 2007 review, if you’re interested). The two co-founders — Benoit Bail and Jerry Gitany – are currently touring Europe on an Agricole Tour to promote and extend the visibility of French island rhums, so their enthusiasm and affection for agricoles is not just a flash in the pan, but something to be taken seriously.

When I consider the pain Josh Miller went through to get the twelve blanc agricoles which he put through their paces the other day (spoiler alert – the Damoiseau 55% won), I consider the Europeans to be fortunate to have much greater resources at their disposal – especially in France, where I tried this yummy fifty percenter. And frankly, when North Americans tell me about their despite for white (so to speak), having had only Bacardis and other bland, filtered-to-within-a-whisker-of-falling-asleep mixing agents whose only claim to fame is their ubiquity, well, here’s one that might turn a few heads and change a few minds.

(83/100)

Other notes

- Outturn 1500 bottles

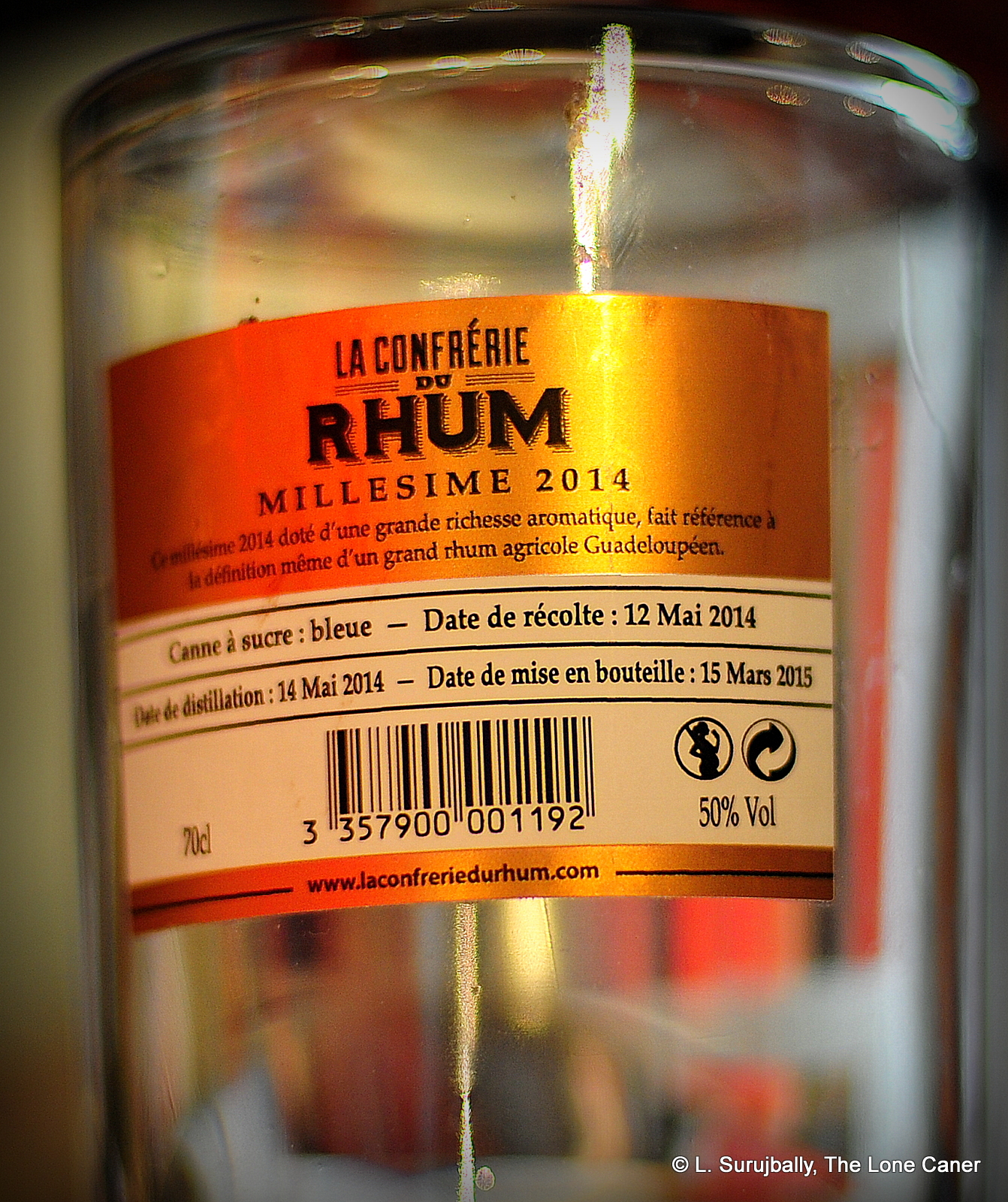

- Source blue cane chopped, crushed, wrung out, soaked and hooched in May 2014, left in steel vats for around six months, and bottled in March 2015.