#327

What a change just a few years have wrought. Back in 2009-2010, cask strength rums were hardly on the horizon, “full proof” drinks were primarily Renegade at 46% with a few dust-gatherers from independent bottlers like Secret Treasures, Cadenhead, Berry Bros., or Samaroli making exactly zero waves in North America, and Velier’s superlative rums issued almost a decade earlier known to few outside Italy. Rum Nation took two years to sell a pair of 1974 and a 1975 25 year old Jamaican rums bottled at 45%….and they were around since 1999!

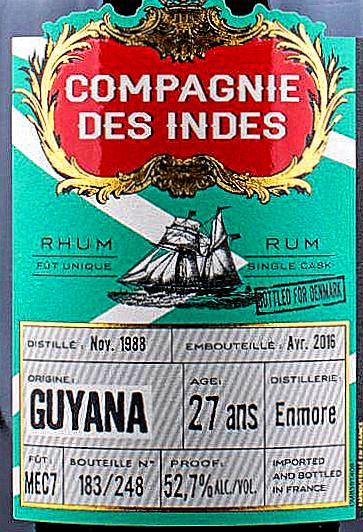

As 2016 comes to a close, observe the continental drift of the landscape: Velier is the mastodon of the full proofs, DDL released its Rares in February, Foursquare and Mount Gay are both issuing powerful and new versions of their old stalwarts, the Jamaicans are undergoing a rennaissance of old estate marques, and previously unremarked and unknown independent bottlers (some new, some not so new) are all clamouring for your attention. Companies like Compagnie des Indes, Ekte, L’Espirit, Kill Devil and others are the vanguard, and more are coming. Even the regular, tried-and-true makers whose names we grew up with, are amping up their rums to 42-43% more often.

In between all of these companies is Rum Nation, that Italian outfit run by Fabio Rossi, whose products I’ve been watching and writing about since 2011, when I bought almost their entire 2010 release line at once. They’ve been making rums since the 1990s (like the two Jamaicans noted above), and over the past three years have attracted equal parts admiration and derision, depending on who’s doing the talking – it’s almost always the matter of additives to their rums; it should be observed that at the top end, it’s not usually the case, like with the 23-26 year old Jamaicans and Demeraras which remain among the best rums of their kind available.

In between all of these companies is Rum Nation, that Italian outfit run by Fabio Rossi, whose products I’ve been watching and writing about since 2011, when I bought almost their entire 2010 release line at once. They’ve been making rums since the 1990s (like the two Jamaicans noted above), and over the past three years have attracted equal parts admiration and derision, depending on who’s doing the talking – it’s almost always the matter of additives to their rums; it should be observed that at the top end, it’s not usually the case, like with the 23-26 year old Jamaicans and Demeraras which remain among the best rums of their kind available.

The Small Batch Rare Rums Collection is Fabio’s last old stocks of Demerara rum, and has been on the drawing boards, so to speak, for quite some time – as DDL and Velier showed us with their own Rares, the decision to issue a rum can be made more than a year in advance of the actual first sales, what with all the bureaucratic hoops and logistics a bottler has to go through to bring the vision to market. Anyway – the Diamond I’m writing about today, the youngest of the three, was from the 1st Batch and is RN’s own foray into the cask-strength market, issued at a rough and ready 58.6%, distilled in 2005 from the double column metal coffey still, and bottled in 2016…the outturn was/is 473 bottles, the presentation of which are the same RN style, but with cardboard tube enclosures, simpler and perhaps more informative labels to go along with them – and which, as always, have the postage stamp motif which has become almost a hallmark of Fabio’s (he used to be a collector in his youth, as I was). And no, no additives as far as I’m aware.

If you’ve been bored to tears by all this set-the-stage introductory material, your immediate and impatient question at the top was most likely, well, how good was the thing? .

All in all, it wasn’t bad – what set it lower on the podium than some others is probably the ageing, which I suspect was not fully tropical (Fabio still has to get back to me on that one but bearing in mind past products, it’s a good bet) and therefore not all the rougher edges had time to be fully integrated with and mellowed by the oak barrels in which it had been aged. It smelled light, with initial easy-to-spot caramel, white toblerone, vanilla and toffee, leavened with some watery fruit (green pears and watermelons), cloves, cumin, marzipan, before settling down to emit some odd background notes of black pepper, sawdust, grapes, raisins, fleshier stoned fruits, bubble gum and a soda pop…maybe pepsi, or 7-up. Not entirely my thing – it was a bit sharp and raw, needed some snap and firmness to make the point more distinct, and the synthesis could have been better.

Diamond rums, of course, have been among my favourites for a while (comparisons with Velier are unavoidable) and what they lack in the fierce pungent originality of the rums from the wooden stills they regain in blending and ageing skill. Some of that was evident when tasting the amber coloured rum – it started off hot, lunging out of the gate with first tastes of cocoa and light coffee, vanilla, some brine, some sweet (good balance there, not too much of either), and a muted explosion of fruits. It was quite a bit lighter in mouthfeel than the PM and Enmore tasted right alongside, which some might mark down because it presents as thin, but to me there’s a world of difference between the two terms – the Doorley’s or an underproof 37.5% rum is thin; well made agricoles are light. So here I think that lightness has to be taken together with the crisp intensity of the tastes that come through, because no scrawny, spavined, rice-eating street cur of a rum could provide this much. There were peaches, apricots, blackberries, cherries, bonbons and caramel sweets, and with water, all that plus some licorice under tight control, and a light woodsy backdrop melding somewhat uneasily with the whole…and a long, slow finish that provided closing notes of licorice, sweets, more fruits (nothing too citrusy or tart here) and, surprisingly enough, a coffee cake with loads of whipped cream.

All this taken into account, was the youngest rum the best of the three or not?

Well…no. I found it somewhat austere, to be honest, a few clear notes coming together with the quiet, restrained sadness of a precise Chopin nocturne or a flute sonata by Debussy, and less of the passionate emotional fire of Beethoven, Verdi, Puccini or Berlioz that almost epitomizes the Guyanese rums when made at the peak of their potential. It requires some more taming, I think, even dialling down — compared with its siblings and a bunch of other Demeraras I tried alongside it, it feels unfinished, like it needed some more ageing to come into its full glory. Whatever. It’s still a very tasty tot, and as long as you take what I said about lightness versus thinness alongside the strength and price and tasting notes together, I don’t think you’ll be too disappointed if you do end up spring for it.

(86/100)