For those who are deep into rumlore, trying the quartet of the National Rums of Jamaica series issued by Velier in 2018 is an exercise I would recommend doing with all four at once, because each informs the other and each has an ester count that must be taken into consideration when figuring out what one wants out of them, and what one gets – and those are not always the same things. If on the other hand you’re new to the field, prefer rums as quiescent as a feather pillow, something that could give the silkiness of a baby’s cheek a raging inferiority complex, and are merely buying the Cambridge 2005 13YO because it is made by Velier and you wanted to jump on the train and see what the fuss is about (or because of a misguided FOMO), my suggestion is to stay on the platform and look into the carriage carefully before buying a ticket.

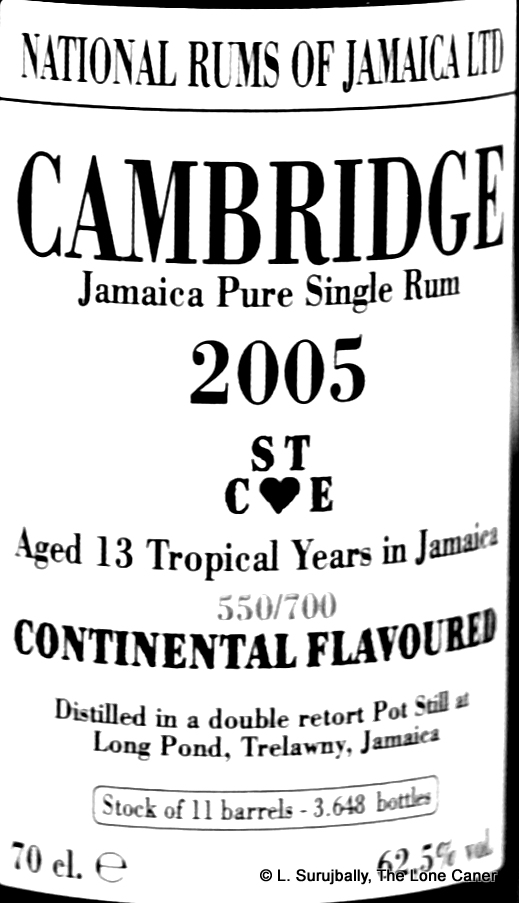

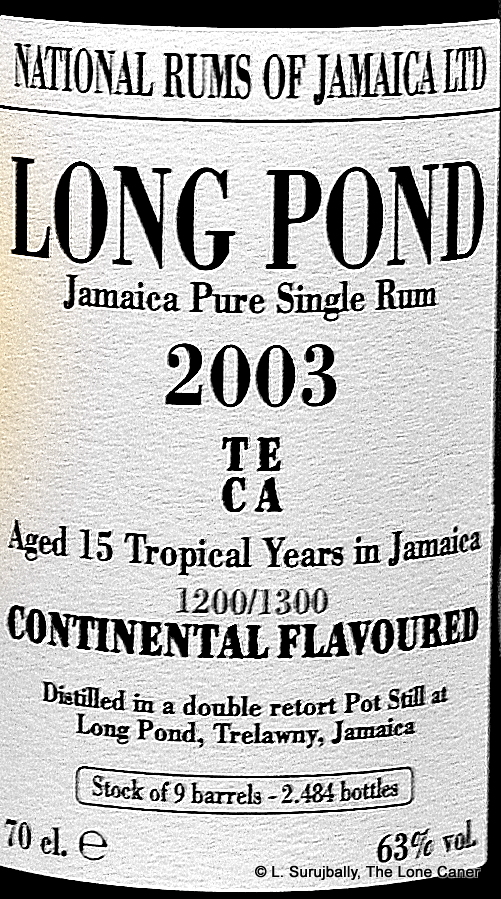

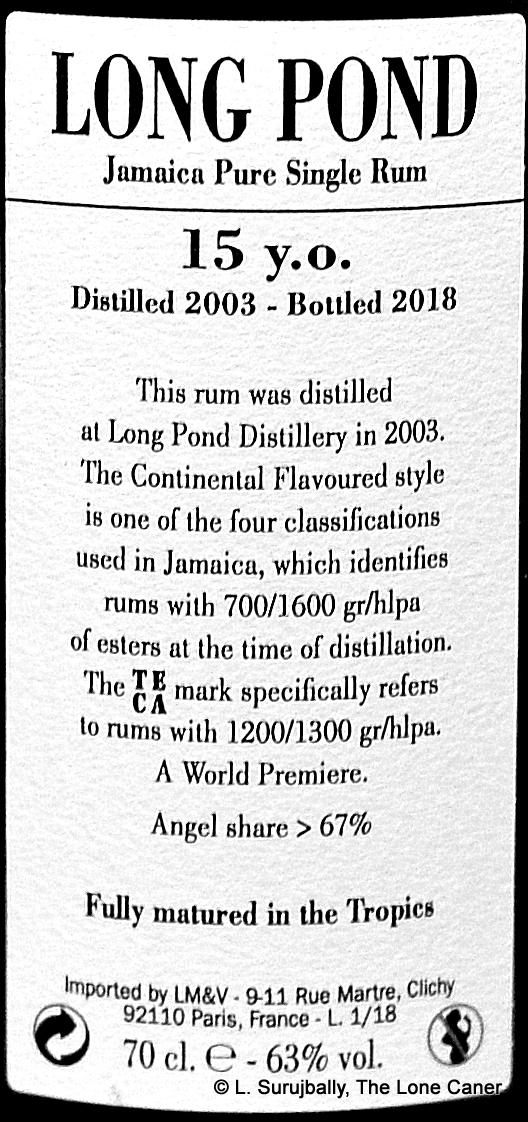

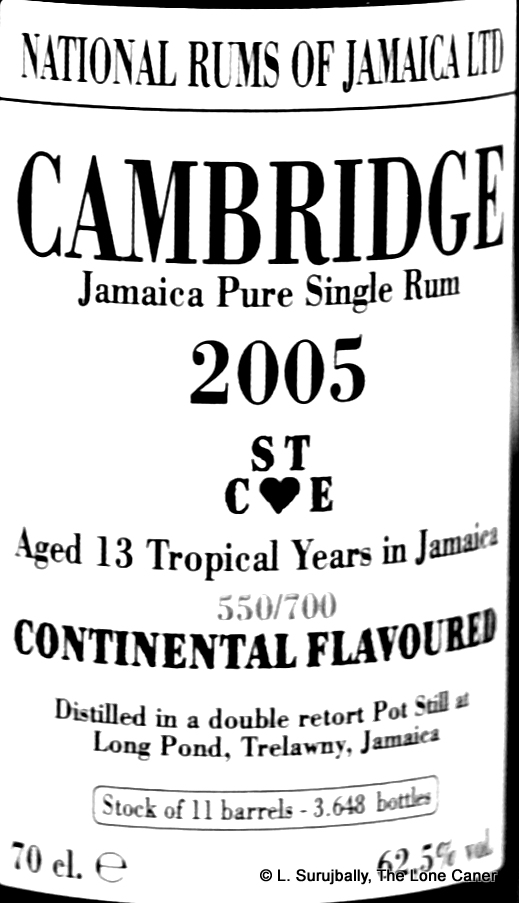

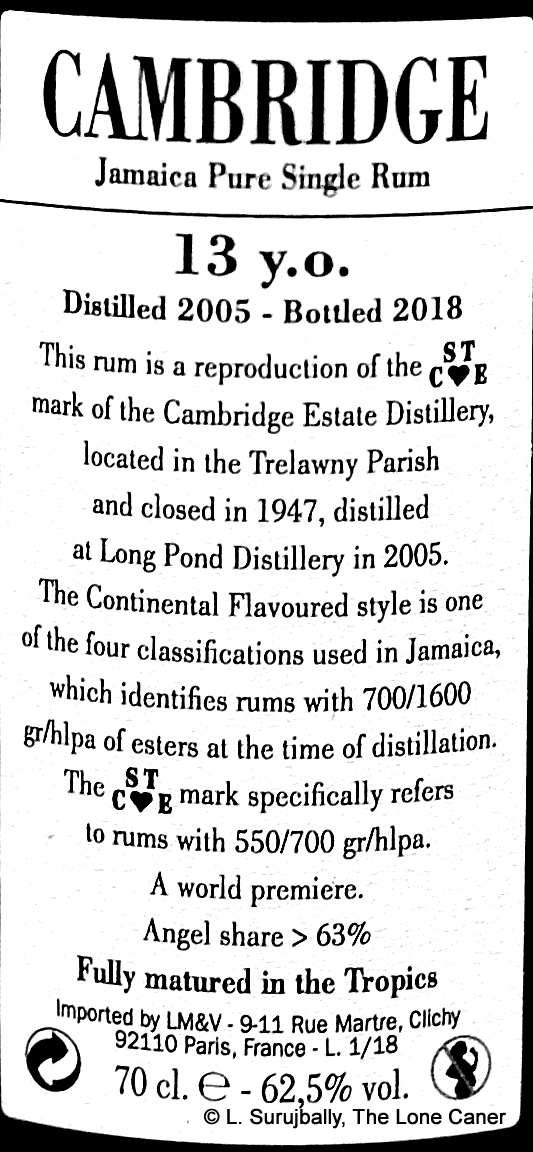

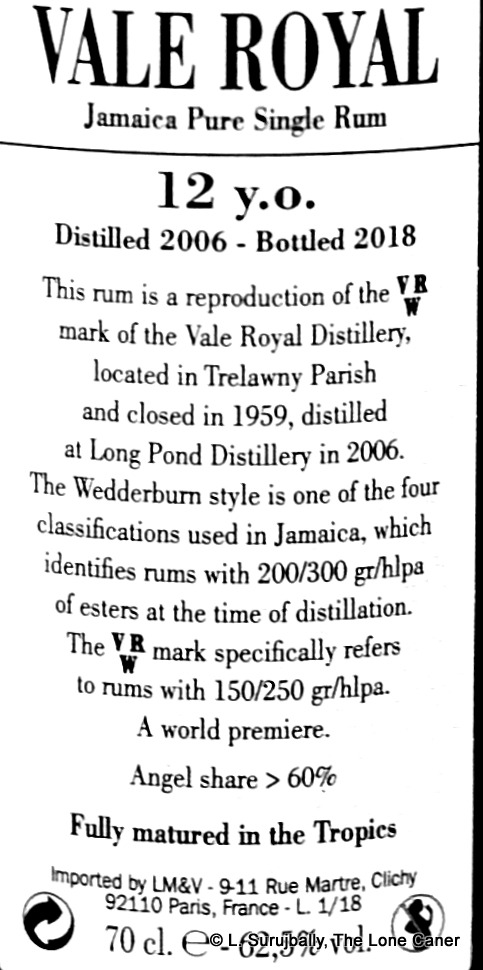

This might sound like paradoxical advice coming from an avowed rum geek, but just follow me through the tasting of this 62.5% bronto, which sported a charmingly erect codpiece of 550 grams of esters (out of a max of 700 grams per hectoliter of alcohol (hlpa) — this moves it way out from the “Common Clean,” “Plummer” and “Wedderburn” categories, and somewhere in between the “Wedderburn” and “Continental Flavoured” (see other notes below), although it is formally listed as being a CF. For comparison, the most furiously esterified rum ever made, the DOK (which is not supposed to be a drinking rum, by the way, but a flavouring ingredient for lesser rums and the Caputo 1973) runs at just about the legal limit of 1600 /hlpa, and most rums with a count worth mentioning pretty much stick in the few hundreds range.

There’s a reason for that. What these esters do is provide a varied and intense and enormously boosted flavour profile, not all of which can be considered palatable at all times, though the fruitiness and light flowers are common to all of them and account for much of the popularity of such rums which masochistically reach for higher numbers, perhaps just to say “I got more than you, buddy”. Maybe, but some caution should be exercised too, because high levels of esters do not in and of themselves make for really good rums every single time. Still, with Luca having his nose in the series, one can’t help but hope for something amazingly new and perhaps even spectacular. I sure wanted that myself.

There’s a reason for that. What these esters do is provide a varied and intense and enormously boosted flavour profile, not all of which can be considered palatable at all times, though the fruitiness and light flowers are common to all of them and account for much of the popularity of such rums which masochistically reach for higher numbers, perhaps just to say “I got more than you, buddy”. Maybe, but some caution should be exercised too, because high levels of esters do not in and of themselves make for really good rums every single time. Still, with Luca having his nose in the series, one can’t help but hope for something amazingly new and perhaps even spectacular. I sure wanted that myself.

And got it, right from the initial nosing of this kinetic rum, which seemed to be straining at the leash the entire time I tried it, ready to blast me in the face with one of the most unique profiles I’ve ever tried. Christ!…It started off with tons of dry jute sacks, dusty cardboard and hay – and then went off on a tangent so extreme that I swear it could make a triangle feel it had more than a hundred and eighty degrees. It opened a huge can of sensory whup-ass with the full undiluted rumstink of an unventilated tannery going full tilt (yes, I’ve been in one), the sort of stark pungency one finds in a hairdressing salon using way too much nail polish remover, and a serious excess of ammonia and hair relaxant…all at the same time. I mean, wow! It’s got originality, I’ll give it that (and the points to go with it) but here is one place where the funk is really a bit much. And yet, and yet….alongside these amazingly powerful fragrances came crisp, clearly-defined fruits,mostly of the sharper variety – pineapple, gooseberries, five-finger, soursop, unripe mangoes, green grapes, red currants, olives, brine, pimentos…I could go on.

What makes the rum so astounding – and it is, you know, for all its off-the-wall wild madness – is the way it keeps developing. In many rums what you get to smell is pretty much, with some minor variation, what you get to taste. Not here. Not even close. Oh the palate is forceful, it’s sharp, it’s as chiselled as a bodybuilder’s abs, and initially it began like the nose did, with glue, ammonia and sweet-clear acetone-perfume bolted on to a hot and full bodied rum. But over time it became softer, slightly creamy, a bit yeasty, minty, and also oddly light, even sweet. Then came the parade of vanilla, peaches, ginger, cardamom, olives, brine, pimentos, salty caramel ice cream, freshly baked sourdough bread and a very sharp cheddar, and still it wasn’t done – it closed off in a long, dry finish laden with attar of roses, a cornucopia of sharp and unripe fleshy fruits (apricots, peaches, apples), rotting bananas, acetones, nail polish and lots and lots of flowers.

I honestly don’t know what to make of a rum this different. It provides everything I’ve ever wanted as an answer to tame rum makers who regularly regurgitate unadventurous rums that differ only in minute ways from previous iterations and famed older blends. This one in contrast is startlingly original, seemingly cut from new cloth — it’s massive, it’s feral, it makes no apologies for what it is and sports a simply ginormous range of flavours. It cannot be ignored just because it’s teetering on the wrong side of batsh*t crazy (which I contend it does). Luca Gargano, if you strain your credulity to the limit, can conceivably make a boring rum…but he’s too skilled to make a bad one, and I think what he was gunning for here was a brown bomber that showcased the island, the distillery, the marque and the ester-laden profile. He certainly succeeded at all of these things…though whether the rum is an unqualified success for the lay-drinker is a much harder question to answer.

You see, there’s a reason such high ester superrums don’t get made very often. They simply overload the tasting circuits, and sometimes such a plethora of intense good things is simply too much. I’m not saying that’s the case here because the balance and overall profile is quite good – just that the rum, for all its brilliantly choreographed taste gyrations, is not entirely to my taste, the ammonia-laden nose is overboard, and I think it’s likely to be a polarizing product – good for Jamaica-lovers, great for the geeks, not so much for Joe Harilall down the road. I asked for new and spectacular and I got both. But a wonderful, amazing, must-have rum? The next Skeldon or 1970s PM, or 1980s Caroni? Not entirely.

(#564)(84/100)

Background notes

(With the exception of the estate section, all remarks here are the same for the four reviews)

This series of essays on the four NRJ rums contains:

In brief, these are all rums from Long Pond distillery, and represent distillates with varying levels of esters (I have elected to go in the direction of lowest ester count → highest, in these reviews). Much of the background has been covered already by two people: the Cocktail Wonk himself with his Jamaican estate profiles and related writings, and the first guy through the gate on the four rums, Flo Redbeard of Barrel Aged Thoughts, who has written extensively on them all (in German) in October 2018. As a bonus, note that a bunch of guys sampled and briefly reviewed all four on Rumboom (again, in German) the same week as my own reviews came out, for those who want some comparisons.

The various Jamaican ester marks

These are definitions of ester counts, and while most rums issued in the last ten years make no mention of such statistics, it seems to be a coming thing based on its increasing visibility in marketing and labelling: right now most of this comes from Jamaica, but Reunion’s Savanna also has started mentioning it in its Grand Arôme line of rums. For those who are coming into this subject cold, esters are the chemical compounds responsible for much of a given rum’s flowery and fruity flavours – they are measured in grams per hectoliter of pure alcohol, a hectoliter being 100 liters; a light Cuban style rum can have as little as 20 g/hlpa while an ester gorilla like the DOK can go right up to the legal max of 1600 at which point it’s no longer much of a drinker’s rum, but a flavouring agent for lesser rums. (For good background reading, check out the Wonk’s work on Jamaican funk, here).

These are definitions of ester counts, and while most rums issued in the last ten years make no mention of such statistics, it seems to be a coming thing based on its increasing visibility in marketing and labelling: right now most of this comes from Jamaica, but Reunion’s Savanna also has started mentioning it in its Grand Arôme line of rums. For those who are coming into this subject cold, esters are the chemical compounds responsible for much of a given rum’s flowery and fruity flavours – they are measured in grams per hectoliter of pure alcohol, a hectoliter being 100 liters; a light Cuban style rum can have as little as 20 g/hlpa while an ester gorilla like the DOK can go right up to the legal max of 1600 at which point it’s no longer much of a drinker’s rum, but a flavouring agent for lesser rums. (For good background reading, check out the Wonk’s work on Jamaican funk, here).

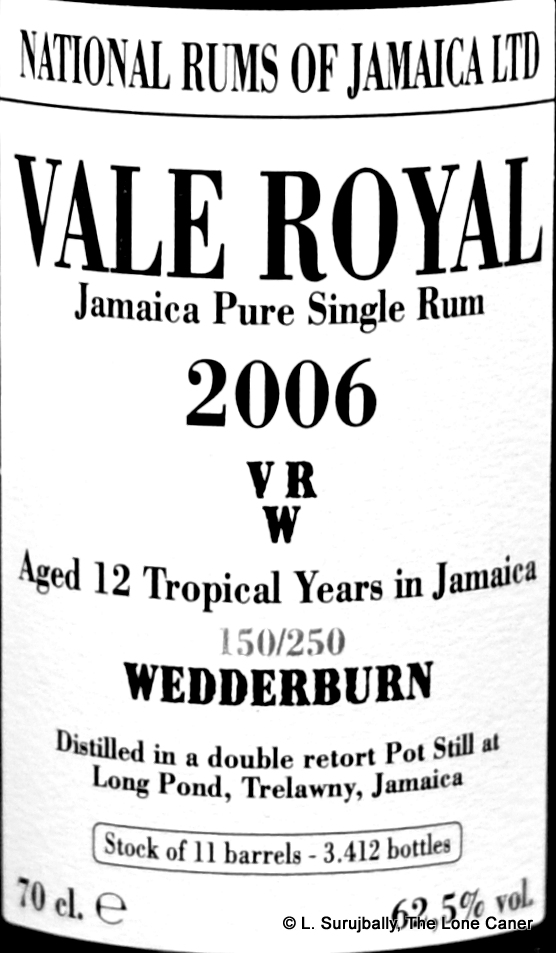

Back in the day, the British classified Jamaican rums into four major styles, and many estates took this a few steps further by subdividing the major categories even more:

Standard Classification

- Common Clean 50-150 gr/hlpa

- Plummer 150-200 gr/hlpa

- Wedderburn 200-300 gr/hlpa

- Continental Flavoured 700-1600 gr/hlpa

Exactly who came up with the naming nomenclature, or what those names mean, is something of a historian’s dilemma, and what they call the juice between 301 to 699 gr/hlpa is not noted, but if anyone knows more, drop me a line and I’ll add the info. Note in particular that these counts reflect the esters after distillation but before ageing, so a chemical test might find a differing value if checked after many years’ rest in a barrel.

Long Pond itself sliced and diced and came up with their own ester subdivisions, and the inference seems to be that the initials probably refer to distilleries and estates acquired over the decades, if not centuries. It would also appear that the ester counts on the four bottles do indeed reflect Long Pond’s system, not the standard notation (tables.

RV 0-20

CQV 20-50

LRM 50-90

ITP /LSO 90-120

HJC / LIB 120-150

IRW / VRW 150-250

HHH / OCLP 250-400

LPS 400-550

STC❤E 550-700

TECA 1200-1300

TECB 1300-1400

TECC 1500-1600

The Estate Name:

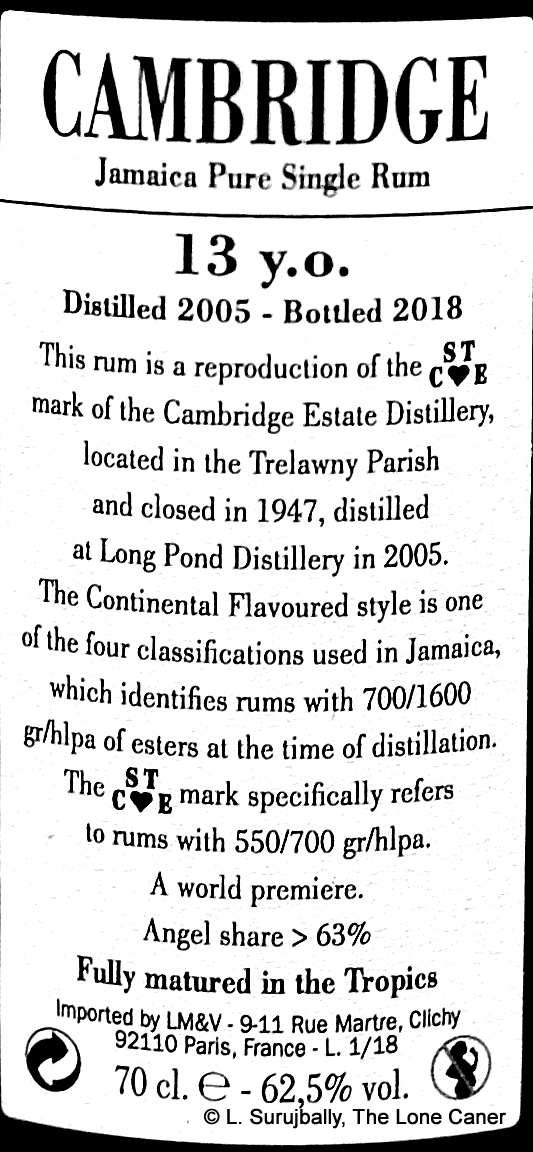

Like the Vale Royal estate and Long Pond itself, Cambridge was also located in Trelawny Parish and has a history covered in greater depth by BAT, here, so I’ll just provide the highlights in the interests of keeping things manageable. Founded in the late 18th century by a family named Barrett (there’s a record of still being in the hand of an Edward Barrett a generation later), it closed its doors just after the Second World War in 1947 by which time another family (or the name-changed original one) called Thompson owned the place. It’s unclear whether the mark STCE (Simon Thompson Cambridge Estate according to the estimable Luca Gargano) was maintained and used because physical stills had been brought over to Long Pond at that time, or whether the Cambridge style was being copied with existing stills.

Whatever the case back then, these days the stills are definitely at Long Pond and the Cambridge came off the a John Dore double retort pot still in 2005. The label reflects a level of 550 g/hlpa esters which is being stated as a Continental Flavoured style, but as I’ve remarked before, the level falls in the gap between Wedderburn and CF. I imagine they went with their own system here.

Note: National Rums of Jamaica is not an estate or a distillery in and of itself, but is an umbrella company owned by three organizations: the Jamaican Government, Maison Ferrand of France (who got their stake in 2017 when they bought WIRD in Barbados, the original holder of the share Ferrand now hold) and Guyana’s DDL.

Technical details are murky. All right, they’re practically non-existent. I think it’s a filtered column still rum, diluted down to standard strength, but lack definitive proof – that’s just my experience and taste buds talking, so if you know better, drop a line. No notes on ageing – however, in spite of one reference I dug up which noted it as unaged, I think it probably was, just a bit.

Technical details are murky. All right, they’re practically non-existent. I think it’s a filtered column still rum, diluted down to standard strength, but lack definitive proof – that’s just my experience and taste buds talking, so if you know better, drop a line. No notes on ageing – however, in spite of one reference I dug up which noted it as unaged, I think it probably was, just a bit.

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the

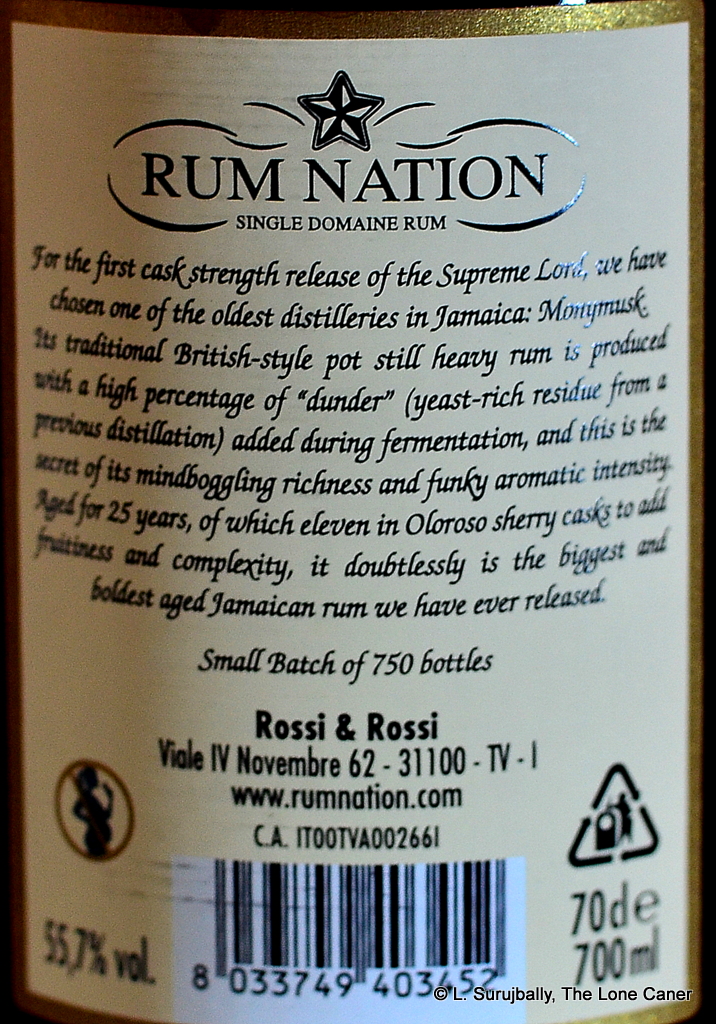

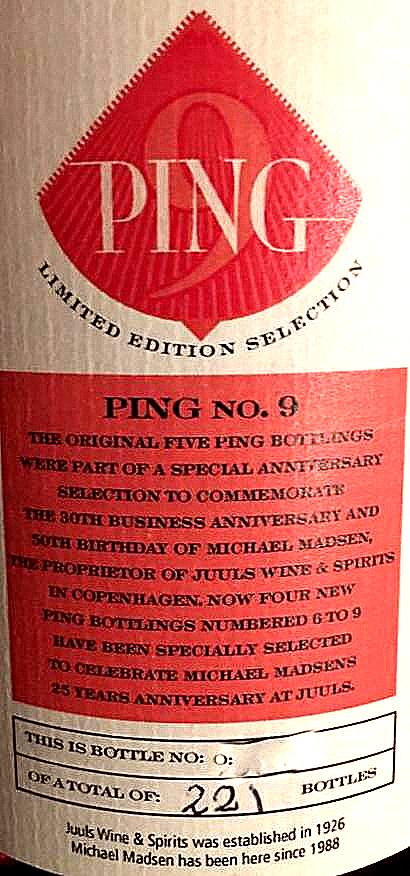

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the  The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

This brings us to the

This brings us to the

In sampling the initial nose of the third rum in the NRJ series, I am not kidding you when I say that I almost fell out of my chair in disbelief. The aroma was the single most rancid, hogo-laden ester bomb I’d ever experienced – I’ve tasted hundreds of rums in my time, but never anything remotely like this (except perhaps the

In sampling the initial nose of the third rum in the NRJ series, I am not kidding you when I say that I almost fell out of my chair in disbelief. The aroma was the single most rancid, hogo-laden ester bomb I’d ever experienced – I’ve tasted hundreds of rums in my time, but never anything remotely like this (except perhaps the  In brief, these are all rums from Long Pond distillery, and represent distillates with varying levels of esters (I have elected to go in the direction of lowest ester count → highest, in these reviews). Much of the background has been covered already by two people: the Cocktail Wonk himself with his

In brief, these are all rums from Long Pond distillery, and represent distillates with varying levels of esters (I have elected to go in the direction of lowest ester count → highest, in these reviews). Much of the background has been covered already by two people: the Cocktail Wonk himself with his

There’s a reason for that. What these esters do is provide a varied and intense and enormously boosted flavour profile, not all of which can be considered palatable at all times, though the fruitiness and light flowers are common to all of them and account for much of the popularity of such rums which masochistically reach for higher numbers, perhaps just to say “I got more than you, buddy”. Maybe, but some caution should be exercised too, because high levels of esters do not in and of themselves make for really good rums every single time. Still, with Luca having his nose in the series, one can’t help but hope for something amazingly new and perhaps even spectacular. I sure wanted that myself.

There’s a reason for that. What these esters do is provide a varied and intense and enormously boosted flavour profile, not all of which can be considered palatable at all times, though the fruitiness and light flowers are common to all of them and account for much of the popularity of such rums which masochistically reach for higher numbers, perhaps just to say “I got more than you, buddy”. Maybe, but some caution should be exercised too, because high levels of esters do not in and of themselves make for really good rums every single time. Still, with Luca having his nose in the series, one can’t help but hope for something amazingly new and perhaps even spectacular. I sure wanted that myself. These are definitions of ester counts, and while most rums issued in the last ten years make no mention of such statistics, it seems to be a coming thing based on its increasing visibility in marketing and labelling: right now most of this comes from Jamaica, but Reunion’s Savanna also has started mentioning it in its Grand Arôme line of rums. For those who are coming into this subject cold, esters are the chemical compounds responsible for much of a given rum’s flowery and fruity flavours – they are measured in grams per hectoliter of pure alcohol, a hectoliter being 100 liters; a light Cuban style rum can have as little as 20 g/hlpa while an ester gorilla like the DOK can go right up to the legal max of 1600 at which point it’s no longer much of a drinker’s rum, but a flavouring agent for lesser rums. (For good background reading, check out the

These are definitions of ester counts, and while most rums issued in the last ten years make no mention of such statistics, it seems to be a coming thing based on its increasing visibility in marketing and labelling: right now most of this comes from Jamaica, but Reunion’s Savanna also has started mentioning it in its Grand Arôme line of rums. For those who are coming into this subject cold, esters are the chemical compounds responsible for much of a given rum’s flowery and fruity flavours – they are measured in grams per hectoliter of pure alcohol, a hectoliter being 100 liters; a light Cuban style rum can have as little as 20 g/hlpa while an ester gorilla like the DOK can go right up to the legal max of 1600 at which point it’s no longer much of a drinker’s rum, but a flavouring agent for lesser rums. (For good background reading, check out the

Consider first the nose. Frankly, I thought it was lovely – not just because it was different (it certainly was), but because it combined the familiar and the strange in intriguing new ways. It started off dusty, musky, loamy, earthy…the sort of damp potting soil in which my wife exercises her green thumb. There was also a bit of vaguely herbal funk going on in the background, dry, like a hemp rope, or an old jute sack that once held rice paddy. But all this was background because on top of all that was the fruitiness, the flowery notes which gave the rum its character – cherries, peaches, pineapples, mixed with salt caramel, vanilla, almonds, hazelnuts and flambeed bananas. I mean, that was a really nice series of aromas.

Consider first the nose. Frankly, I thought it was lovely – not just because it was different (it certainly was), but because it combined the familiar and the strange in intriguing new ways. It started off dusty, musky, loamy, earthy…the sort of damp potting soil in which my wife exercises her green thumb. There was also a bit of vaguely herbal funk going on in the background, dry, like a hemp rope, or an old jute sack that once held rice paddy. But all this was background because on top of all that was the fruitiness, the flowery notes which gave the rum its character – cherries, peaches, pineapples, mixed with salt caramel, vanilla, almonds, hazelnuts and flambeed bananas. I mean, that was a really nice series of aromas. The various Jamaican ester marks

The various Jamaican ester marks

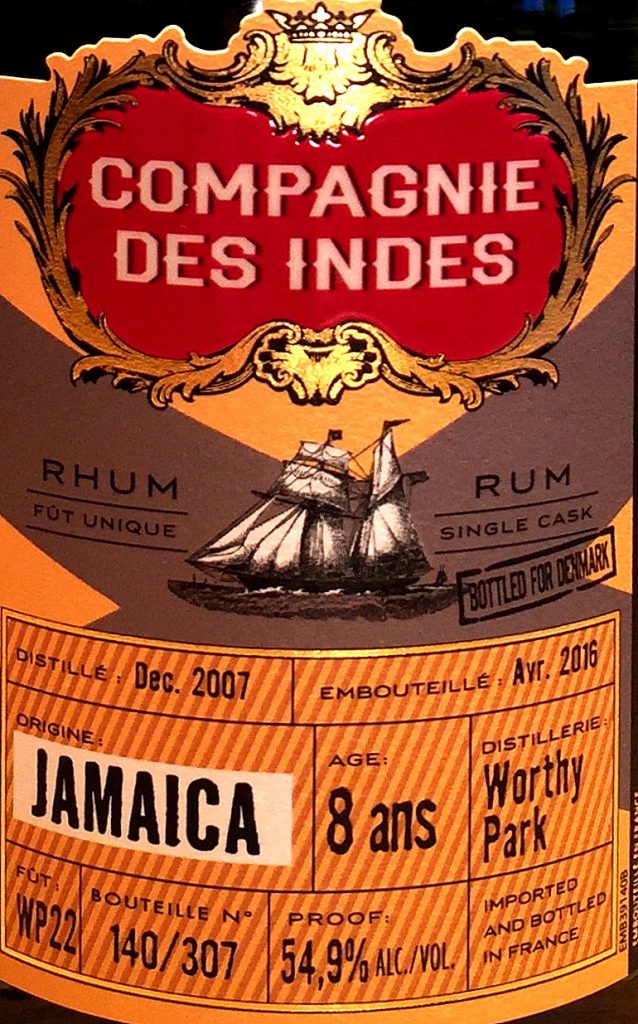

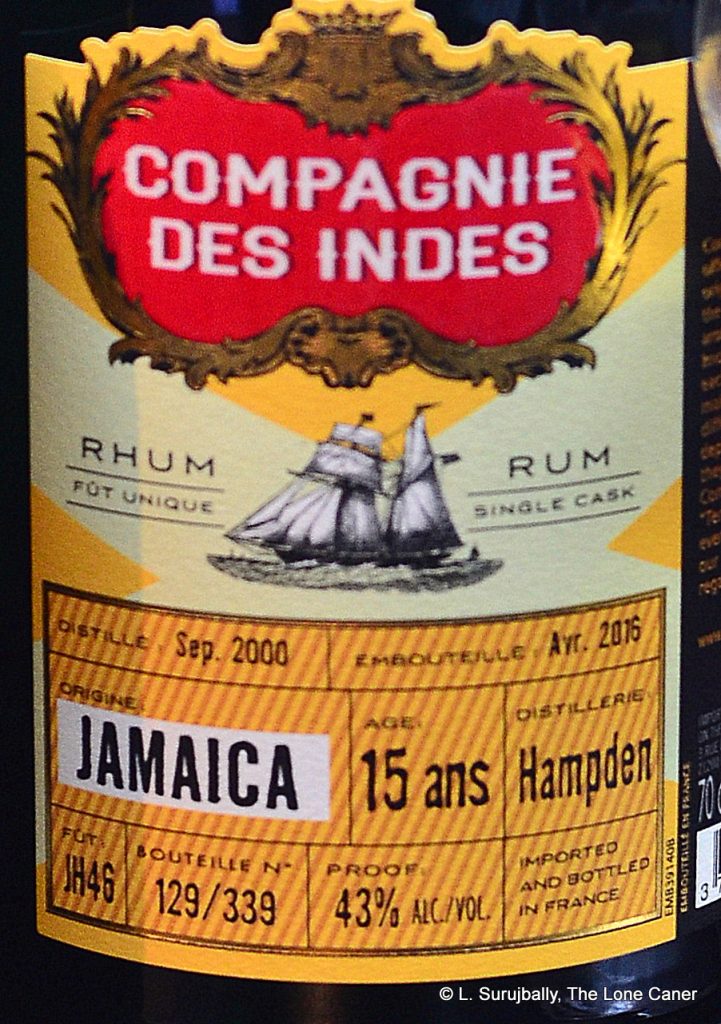

So, given how many Jamaicans are on the scene these days, how does this young, continentally aged 55.9% golden rum fare? Not too shabbily. It’s strong but very approachable, even on the nose, which doesn’t waste any time getting started but announces its ester-rich aromas immediately and with authority: acetone, nail polish and some rubber plus a smell of righteous funk (spoiling fruits, rotten bananas, that kind of thing). Its relative youth is apparent in the uncouth sharpness of the initial aromas, but once one sticks with it, it settles into its own special groove, calms itself down and does a neat little balancing act between sharper scents of citrus, cider, apples, hard yellow mangoes and green grapes, and softer ones of bananas, cumin, vanilla, marshmallows and cloves.

So, given how many Jamaicans are on the scene these days, how does this young, continentally aged 55.9% golden rum fare? Not too shabbily. It’s strong but very approachable, even on the nose, which doesn’t waste any time getting started but announces its ester-rich aromas immediately and with authority: acetone, nail polish and some rubber plus a smell of righteous funk (spoiling fruits, rotten bananas, that kind of thing). Its relative youth is apparent in the uncouth sharpness of the initial aromas, but once one sticks with it, it settles into its own special groove, calms itself down and does a neat little balancing act between sharper scents of citrus, cider, apples, hard yellow mangoes and green grapes, and softer ones of bananas, cumin, vanilla, marshmallows and cloves.

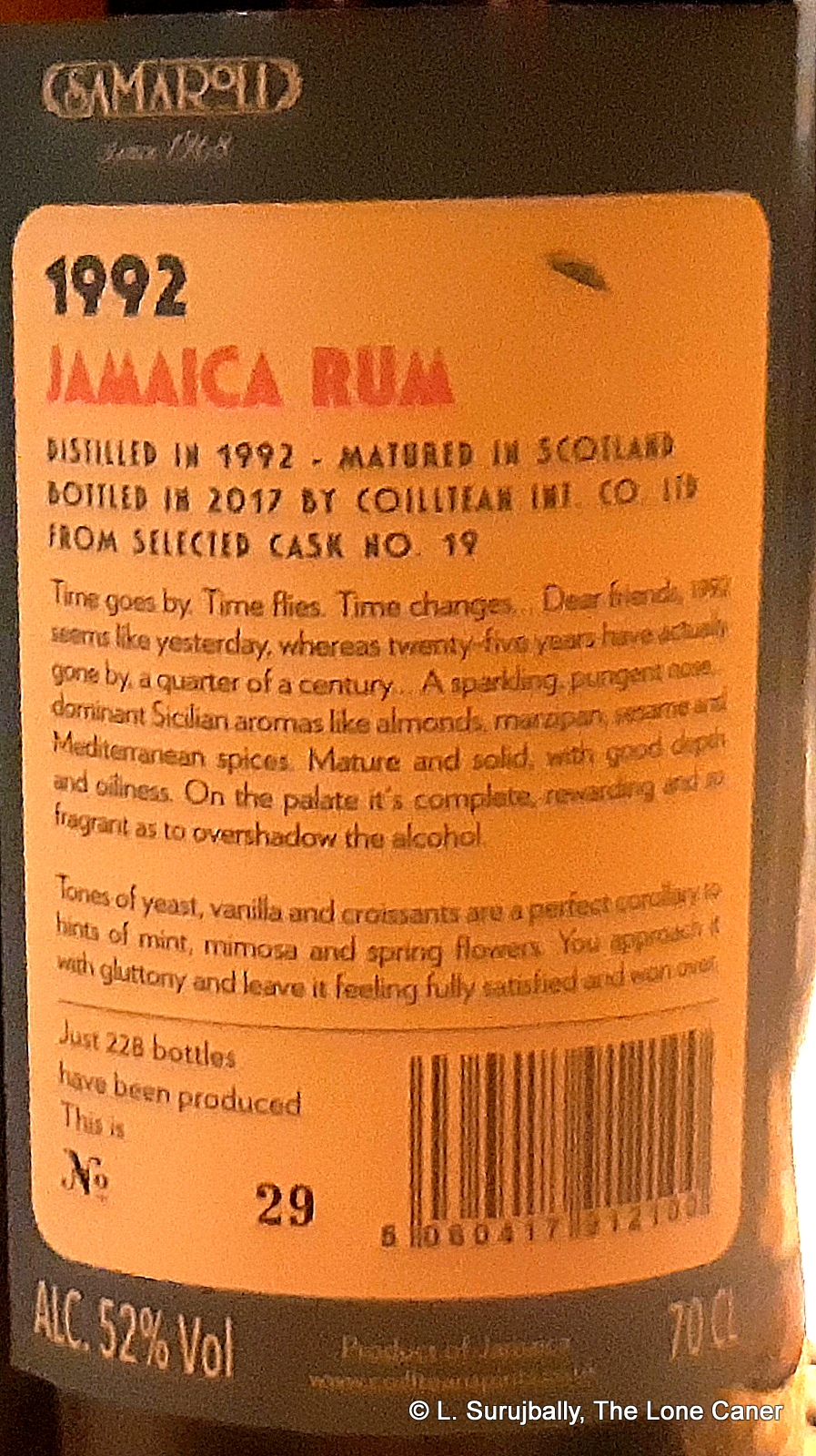

And the taste, the palate, the way it comes together, it’s masterful. At 52% it’s downright near damned perfect – the the balance between mouth puckering citrus plus laid back funk, and easier, softer flavours is unbelievably well done. Soda pop, honey, cereal, red currants, raspberries, fanta and orange zest dance exuberantly cross the tongue, never faltering, never allowing any one piece to dominate. Like an exquisitely choreographed dance number, the molasses, vanillas and fruits (peaches, yellow plums, pears, ripe yellow Thai mangoes) tango alongside sharper notes of citrus, lemon zest, overripe bananas, sandalwood and ginger. Even the finish is spectacular – just long enough, just sharp enough, just mellow enough, allowing each of the individually discerned flavours of fruits, toffee, chocolate and citrus to come out on stage one last time for a bow, before fading back and making way for the next one

And the taste, the palate, the way it comes together, it’s masterful. At 52% it’s downright near damned perfect – the the balance between mouth puckering citrus plus laid back funk, and easier, softer flavours is unbelievably well done. Soda pop, honey, cereal, red currants, raspberries, fanta and orange zest dance exuberantly cross the tongue, never faltering, never allowing any one piece to dominate. Like an exquisitely choreographed dance number, the molasses, vanillas and fruits (peaches, yellow plums, pears, ripe yellow Thai mangoes) tango alongside sharper notes of citrus, lemon zest, overripe bananas, sandalwood and ginger. Even the finish is spectacular – just long enough, just sharp enough, just mellow enough, allowing each of the individually discerned flavours of fruits, toffee, chocolate and citrus to come out on stage one last time for a bow, before fading back and making way for the next one I don’t know what they did differently in this rum from others they’ve issued for the last forty years, what selection criteria they used, but

I don’t know what they did differently in this rum from others they’ve issued for the last forty years, what selection criteria they used, but

On the palate, I didn’t think it could quite beat out the CdI Worthy Park (which was half its age, though quite a bit stronger); but it definitely had more force and more uniqueness in the way it developed than the Longpond and the Mezans. It started with cherries, going-off bananas mixed with a delicious citrus backbone, not too excessive. After ten minutes or so it opened further into a medium sweet set of fruits (peaches, pears, apples), and showed notes of oak, cinnamon, some brininess, green grapes, all backed up by delicate florals that were very aromatic and provided a good background for the finish. That in turn glided along to a relatively serene, slightly heated medium-long stop with just a few bounces on the road to its eventual disappearance, though with little more than what the palate had already demonstrated. Fruitiness and some citrus and cinnamon was about it.

On the palate, I didn’t think it could quite beat out the CdI Worthy Park (which was half its age, though quite a bit stronger); but it definitely had more force and more uniqueness in the way it developed than the Longpond and the Mezans. It started with cherries, going-off bananas mixed with a delicious citrus backbone, not too excessive. After ten minutes or so it opened further into a medium sweet set of fruits (peaches, pears, apples), and showed notes of oak, cinnamon, some brininess, green grapes, all backed up by delicate florals that were very aromatic and provided a good background for the finish. That in turn glided along to a relatively serene, slightly heated medium-long stop with just a few bounces on the road to its eventual disappearance, though with little more than what the palate had already demonstrated. Fruitiness and some citrus and cinnamon was about it.

Rumaniacs Review #080 | 0516

Rumaniacs Review #080 | 0516

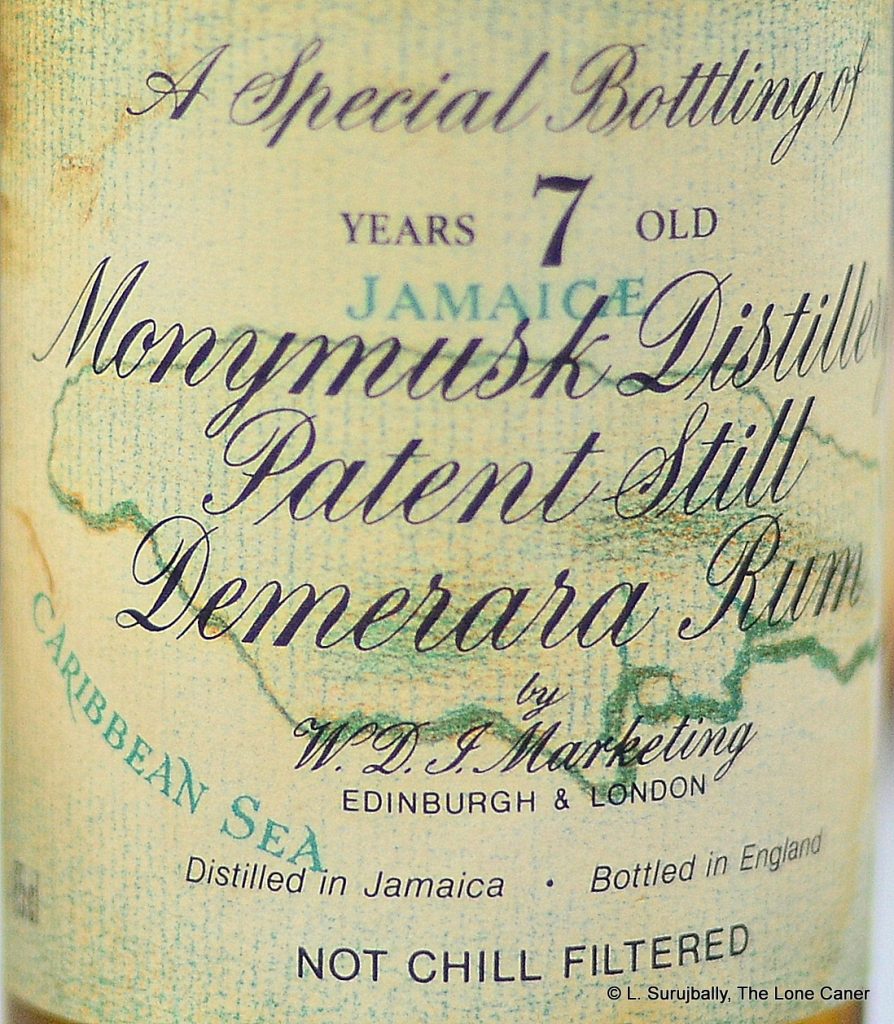

Nose – Yeah, no way this is from Mudland. The funk is all-encompassing. Overripe fruit, citrus, rotten oranges, some faint rubber, bananas that are blackened with age and ready to be thrown out. That’s what seven years gets you. Still, it’s not bad. Leave it and come back, and you’ll find additional scents of berries, pistachio ice cream and a faint hint of flowers.

Nose – Yeah, no way this is from Mudland. The funk is all-encompassing. Overripe fruit, citrus, rotten oranges, some faint rubber, bananas that are blackened with age and ready to be thrown out. That’s what seven years gets you. Still, it’s not bad. Leave it and come back, and you’ll find additional scents of berries, pistachio ice cream and a faint hint of flowers.

Say what you will about tropical ageing, there’s nothing wrong with a good long continental slumber when we get stuff like this out the other end. Again it presented as remarkably soft for the strength, allowing tastes of fruits, light licorice, vanilla, cherries, plums, and peaches to segue firmly across the tongue. Some sea salt, caramel, dates, plums, smoke and leather and a light dusting of cinnamon and florals provided additional complexity, and over all, it was really quite a good rum, closing the circle with a lovely long finish redolent of a fruit basket, port-infused cigarillos, flowers and a few extra spices.

Say what you will about tropical ageing, there’s nothing wrong with a good long continental slumber when we get stuff like this out the other end. Again it presented as remarkably soft for the strength, allowing tastes of fruits, light licorice, vanilla, cherries, plums, and peaches to segue firmly across the tongue. Some sea salt, caramel, dates, plums, smoke and leather and a light dusting of cinnamon and florals provided additional complexity, and over all, it was really quite a good rum, closing the circle with a lovely long finish redolent of a fruit basket, port-infused cigarillos, flowers and a few extra spices.