Every year, especially as the Madeira rumfest comes around, there is a flurry of posts and interest about rums from the islands of that Portuguese Autonomous Region (it’s one of two such regions – the other is the Azores). The better known rums originating there are from the distilleries of O Reizinho, Engenho Novo (which makes William Hinton rums) and Engenhos do Norte, and these three rub shoulders with yet others like Abel Fernandes, Vinha Alta and Engenhos da Calheta. Not surprisingly, there are occasional independent releases as well, such as those from Rum Nation and That Boutique-y Rum Co.

Every year, especially as the Madeira rumfest comes around, there is a flurry of posts and interest about rums from the islands of that Portuguese Autonomous Region (it’s one of two such regions – the other is the Azores). The better known rums originating there are from the distilleries of O Reizinho, Engenho Novo (which makes William Hinton rums) and Engenhos do Norte, and these three rub shoulders with yet others like Abel Fernandes, Vinha Alta and Engenhos da Calheta. Not surprisingly, there are occasional independent releases as well, such as those from Rum Nation and That Boutique-y Rum Co.

One of the reasons Madeira excites interest at all is because they are one of the few countries covered by its own GI (the Madeiran Indicação Geográfica Protegida), and so can legally and properly – at least within the EU – use the term agricole when referring to their cane juice rums (which is practically all of them). Yet, paradoxically, they remain relatively niche products which have only recently – which is to say, within the last decade or so – started to make bigger waves in the rum world, and few writers have spent much time on their products: WhiskyFun has done the most, with eight and there’s a scattering of others from Single Cask Rum, Rum Barrel, The Fat Rum Pirate and myself.

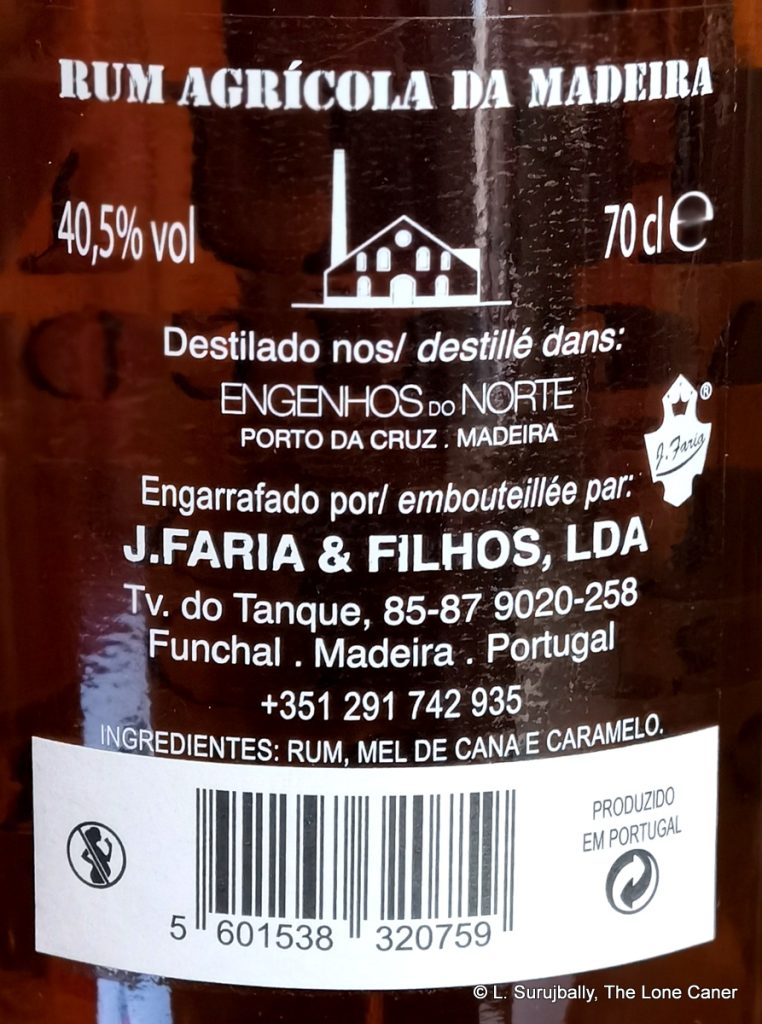

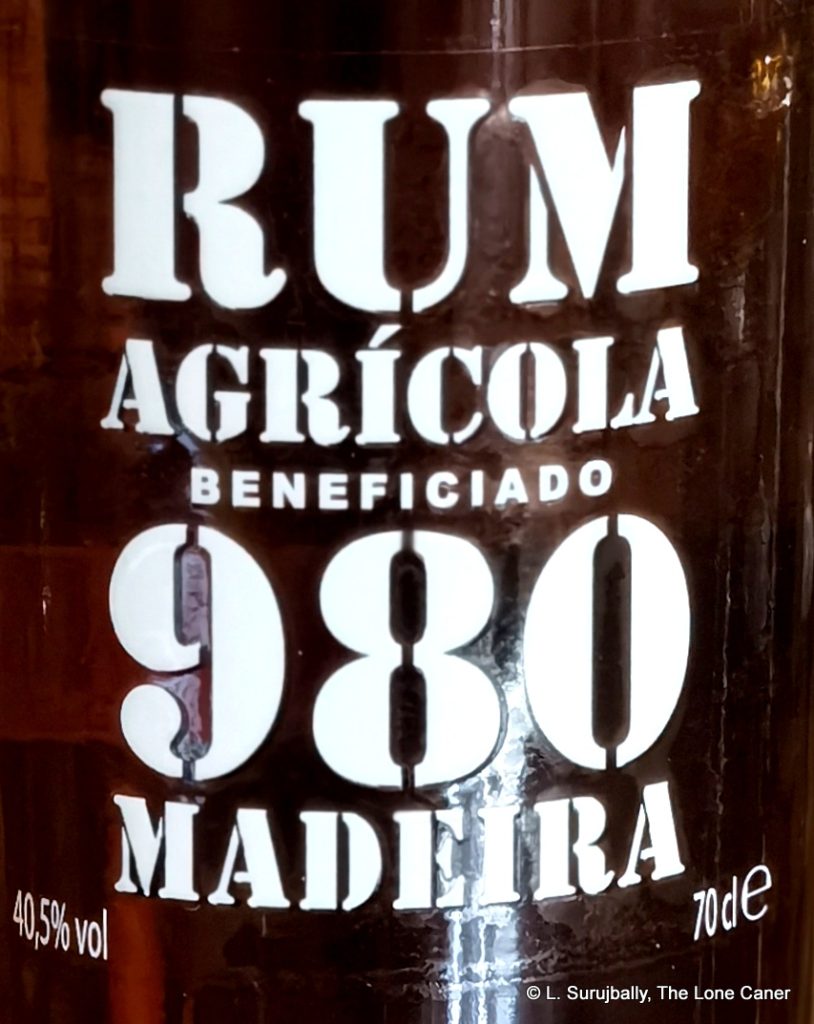

Today we’ll begin a few Madeiran reviews to raise that visibility a bit more, with some rums from what is perhaps the largest of the distilleries, Engenhos do Norte: although google translate will tell you that the Portuguese word engenho means “ingenuity” it really translates into “sugar mill”, which is what most of these companies started out as. Engenhos do Norte was formed by a merger of some fifty mills in either 1927 or 1928, depending on the source — they were forced to come together to remain economically viable (see “Other notes”, below). Their best known brands are the 970 series (introduced in 1970, which is not a coincidence), Branca and Larano, though of late they’ve added more.

One of the more recent additions is the Rum Agrícola Beneficiado 980 — that “980” is an odd shorthand for the year it was introduced, which is to say, 1980 — which is a fresh cane juice rum, 40.5% ABV, column-still made and left to sleep: the final blended rum is from rums aged 3, 6 and 21 years, and although it is not mentioned what kind of barrels are used, I have one reference that it is French Oak and have sent an inquiry down to Engenhos to ask for more details. The proportions of the aged components are unstated, but attention should be paid to the word “beneficiado” (beneficiary) – what this means is that a little cane honey has been added round out the profile, which may be why a hydrometer test, or even straight tastings, tend to comment on a slight sweetness to the profile (it is this which the words on the back label “+ mel de cana e caramelo” mean).

One of the more recent additions is the Rum Agrícola Beneficiado 980 — that “980” is an odd shorthand for the year it was introduced, which is to say, 1980 — which is a fresh cane juice rum, 40.5% ABV, column-still made and left to sleep: the final blended rum is from rums aged 3, 6 and 21 years, and although it is not mentioned what kind of barrels are used, I have one reference that it is French Oak and have sent an inquiry down to Engenhos to ask for more details. The proportions of the aged components are unstated, but attention should be paid to the word “beneficiado” (beneficiary) – what this means is that a little cane honey has been added round out the profile, which may be why a hydrometer test, or even straight tastings, tend to comment on a slight sweetness to the profile (it is this which the words on the back label “+ mel de cana e caramelo” mean).

This sweetness is not, however, immediately noticeable when nosing the rum; initially the scent is one of cardboard, brine, light olives and dates, combined with damp tea leaves and aromatic tobacco. Pralines and a caramel macchiato, cloves and milk – what an odd nose, the more so because it presents very little more commonly accepted agricole elements. There’s a bit of yoghurt mixed up with Dr. Pepper, ginger ale, a kind of sharp and bubbly soda pop, and behind it all, that sense of an overripe orange beginning to go off.

Similarly disconcerting notes appear when tasting it: it’s a bit rough, a bit dry, with rubber, acetones, and brine combining uneasily with honey, vanilla, caramel, toffee and badly made fudge. You can probably pick out additional hints of sweet vanilla ice cream, some tartness of guavas, a touch of citrus – not much more. The finish completes the tasting by being short, mild and inoffensive, presenting a few last caramel and molasses notes set off with Dr. Pepper, licorice, raisins and some oranges. It’s okay, but very different from any agricole you’ve likely tried before, which is both good and bad, depending on your preferences.

Overall, I think the Beneficiado’s weakness is that the freshness of a good grassy, herbal, fruity offset just isn’t there…and if it is, it’s too mild to make a dent. It’s like tasting flavoured fine sandpaper, really, and at just a hair over forty percent strength, it’s too thin to present with any serious assertiveness. Does it work on its own level, with what it actually is (as opposed to what I was expecting, or wished for)? To some extent, yes — it just doesn’t go far enough to capitalise on its few strengths, and therefore what we get is a stolid, rather dour rum, one that lacks those sparkling, light aspects that would balance it better, and make it an agricole worth seeking out.

(#955)(79/100) ⭐⭐⭐

- It’s long been known that sugar cane migrated from Indonesia to India to the Mediterranean, and was being cultivated on Madeira by the first half of the 15th century. From there it jumped to the New World, but sugar remained a profitable cash crop in Madeira (the main island, which gave its name to the group) and the primary engine of the island’s economy for two hundred years.

- For centuries, aside from their famed fortified wines, white rum was all Madeira was known for, and just about all of it was made from small family-owned sugar cane plots, consumed locally as ponchas, and as often considered to be moonshine as a legitimate product. Because of the small size of the island a landed aristocracy based on the system of large plantations never took off there.

- That said, for all its profitability and importance, the sugar industry has been on the edge of a crisis for most of its history: competition from Brazil in the 16th century, sugar cane disease in the 17th, leading to alternative (and competitor) crops like grapes (which led to a much more profitable wine industry) in the 17th and 18th centuries, a resurgence of fungal disease in the late 19th century; the restriction of available land for cane farming in the 20th century (especially in the 1920s and 1930s) … all these made it difficult to have a commercial sugar industry there – no wonder the mills tried to band together. By the 1980s sugar cane farming was almost eliminated as a commercial cash crop, yet even though sugar continued to decline in prices on the world markets — due to cheaper sources of supply in India, Brazil and elsewhere, as well as the growing health consciousness of first world consumers — it stubbornly refused to die. It was kept alive on Madeira partially due to the ongoing production of rum, which in the 21st century started to become a much more important revenue generator than sugar had been, and led to the resurgence of the island as a quality rum producer in its own right.

- In the early 2010s, the Portuguese government started to incentivize the production of aged rum on Madeira. Several producers started laying down barrels to age, one of which was Engenhos do Norte – however the lack of an export market made them sell occasional barrels, or bottle for third parties. That’s how, for example, we got the Boutique-y Madeira rum from 2019.

- The distillery is located in the north of Madeira in the small town of Porto da Cruz, and considered part of Portugal (even though geographically it’s closer to Africa).

- The rum is derived from juice deriving from fresh cane run through a crusher powered by a steam engine, fermented for about 4-5 days, passed through a columnar barbet still and then left to age in French oak barrels.

Could a rum tropically aged for that long be anything but a success? Certainly the comments on the

Could a rum tropically aged for that long be anything but a success? Certainly the comments on the