There’s a reason I don’t buy many rums from the relatively recently established indie bottler of the Rum Sponge, and that’s all about the price. It’s not that I can’t afford one here or there, but to get them all is just too much, and leaves me like a smelly over-the-hill mendicant whining for samples from the more generously endowed. In this case, however, a Calgary Book Club whisky lover bought a bottle and brought it along just to have the rowdies try it, and I was able to sample it without denuding my already slim purse.

For those who are not familiar with it, Rum Sponge is a UK indie bottler, an offshoot of Angus MacRaild’s whisky facing Whisky Sponge brand, itself a part of his company Decadent Drinks. Angus has had an eponymous whisky blog running since about 2013 with witty and insightful posts on the subject, and a few years ago became a second contributor to Serge Valentin’s famed review site Whiskyfun. I don’t know how long he’s been bottling whiskies, but rums only started to come out around 2020 or so.

Edition No.1 rum, a Caroni, was issued in that year, and by 2025 Rum Sponge has released at least 35 different editions. Just about all are single casks (though there are a few blends) and characterized by Angus’s desire to issue rums that are distillate driven, which is something that is also part of his whisky bottling philosophy. I’ve tasted a few, and they’re pretty good for the most part, if expensive, and limited in geographical scope – all so far derive from only three countries: Guyana, Trinidad or Jamaica.

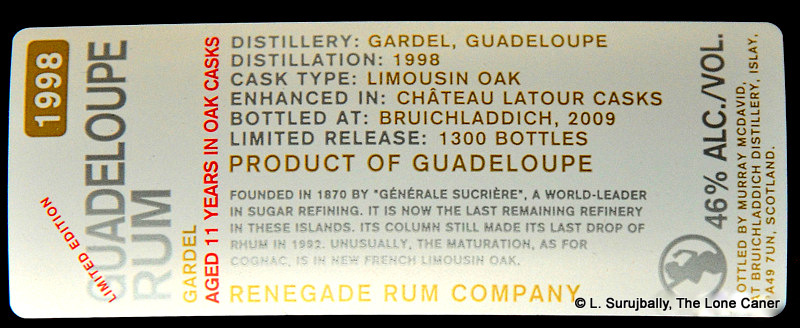

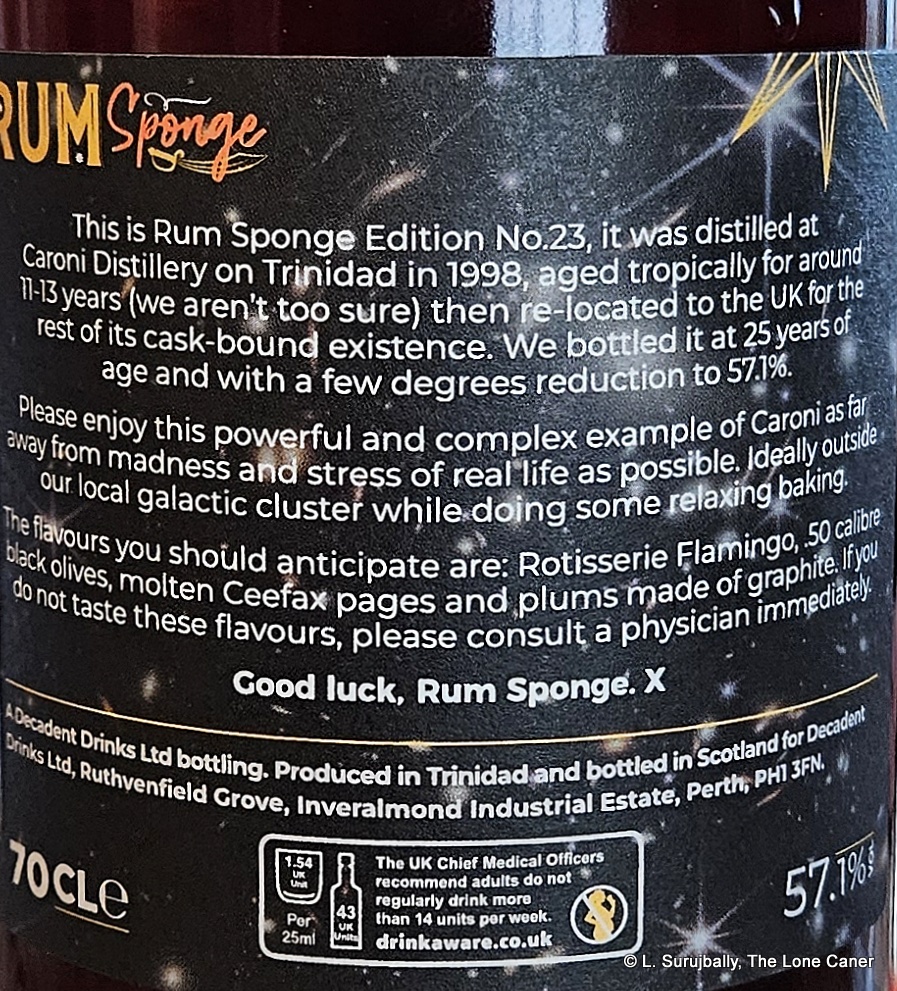

The rum we’re looking at today is from Caroni, a 1998 distillate, aged 25 years, and is Edition No.23. The bottle remarks that it was aged some 11-13 years in Trinidad and the remainder in the UK, has a strength of 57.1%, a single barrel 250-bottle outturn, all of which is nice: yet curiously it doesn’t say whether it is column or pot or blend, which is an odd omission.

Be that as it may, I have to admit the rum is a very very good one: the man knows how to pick ‘em. Consider first the nose: it starts of dry, tannic, and has the immediate sense of bitter high-octane unsweetened dark chocolate. It melds well with caramel, molasses, vanilla and icing sugar, which linger for a while before being added to by dates, prunes, plums, dark olives, a little brine and (get this!) printer ink cartridges and iodine. That’s quite a nose to unpack, trust me.

The palate is similarly intriguing and delicious: it tastes of tannins, crushed walnuts, almonds and black chocolate, and adds to it with more dark fruits (plums, prunes, etc). There are notes of caramel and vanilla, and the slightly bitter tannins take something of a back seat now, with a sweeter fruity aspect coming to the fore – five finger (carambola), peaches, very ripe mangoes, and orange peel. It’s really quite tasty, and it slides into a surprisingly gentle yet long-lasting denouement of caramel, molasses, sugar water and fruitness that’s enormously alluring.

Overall, I like the way it segues from a crisp and almost bitter start to something mellower and sweeter, deeper and more rounded, as it opens up. The balance is excellent and the rum can be sipped with ease – the whisky anoraks who tried it were all quite fulsome in their praises, as I was, so it has an audience beyond just the deep rum divers who dissect every nuance of favoured distilleries.

Yet, let’s be clear. There is little here that screams Caroni. The fusel oils, the dark petrol and kerosene tastes we associate with the type are mostly absent, so this is not a Caroni one should be starting with if one wishes to get a handle on the style – therein will lie disappointment. And then there’s the matter of the price – it’s Can$550. I can’t speak of the cost structure for Angus’s company or how much the barrel itself cost to buy or what ancillaries he had to pay for, but with so many other indies putting out equally aged rums over the last decade which are cheaper and of good quality, that just seems to be too much, even for a famous, closed distillery with limited remaining stocks.

Yet, let’s be clear. There is little here that screams Caroni. The fusel oils, the dark petrol and kerosene tastes we associate with the type are mostly absent, so this is not a Caroni one should be starting with if one wishes to get a handle on the style – therein will lie disappointment. And then there’s the matter of the price – it’s Can$550. I can’t speak of the cost structure for Angus’s company or how much the barrel itself cost to buy or what ancillaries he had to pay for, but with so many other indies putting out equally aged rums over the last decade which are cheaper and of good quality, that just seems to be too much, even for a famous, closed distillery with limited remaining stocks.

So based on those standards, I’d have to say that as a Caroni, the rum fails, and one would have to be a serious aficionado to pay the price to get it. But man, as a rum, just a rum – the thing is quietly outstanding. And I’m seriously glad I got chance to try it. It’s worth it for that alone.

(#1121)(90/100) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Other notes

The nose doesn’t help narrow down the origin (though I have my suspicions), and the palate doesn’t either – but it

The nose doesn’t help narrow down the origin (though I have my suspicions), and the palate doesn’t either – but it