#365

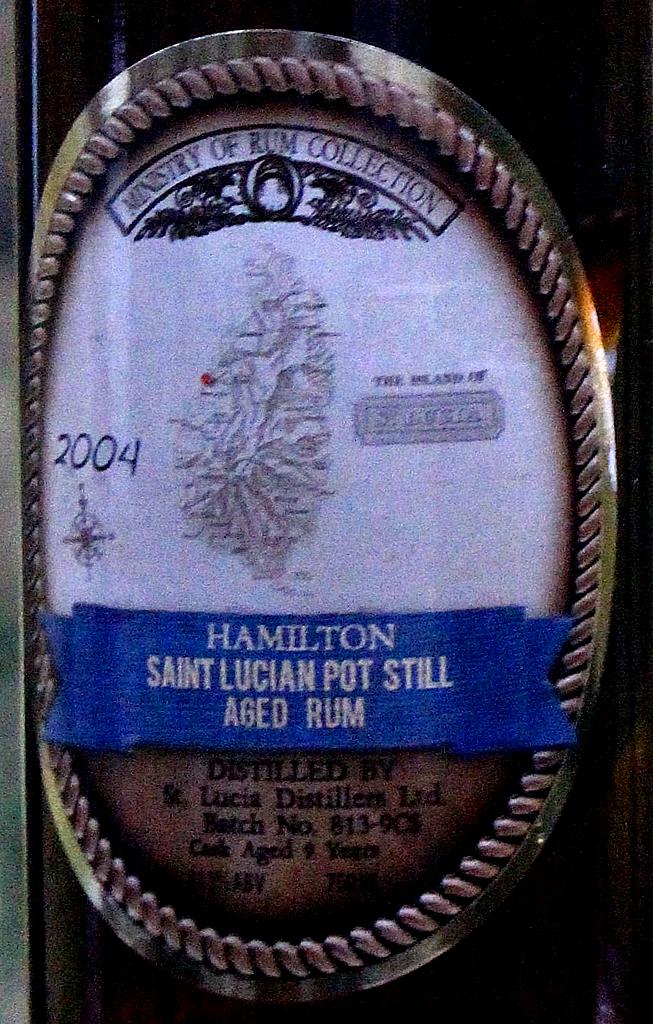

Just about everyone in the rum world knows the name of Ed Hamilton. He was the first person to set up a website devoted to rum (way back in 1995), and many of us writers who began our own blogs in the 2000s or early ‘teens — Tiare, Tatu, Chip, myself and others — started our online lives writing in and debating on the forums of the Ministry of Rum. He has written books about rum, ran tasting sessions for years, and is now a distributor for several brands around the USA. A few years ago, he decided to get into the bottling game as well…and earned quite a fan base in North America, because almost alone among the producers in the US, he went the independent bottler route, issuing his juice at cask strength, thereby helping to popularize the concept to a crowd that had to that point just been mooning over the indie output from Europe without regularly (or ever) being able to get their hands on any.

This rum was distilled in 2004 on a Vendome pot still by St. Lucia Distillers, who also make the Admiral Rodney, 1931, Forgotten Casks and Chairman’s Reserve, if you recall. They have both a Vendome pot still and a John Dore pot still (as well as a smaller one, and the rums mentioned above are made by blending output from all in varying proportions) – Mr. Hamilton deliberately chose the Vendome distillate for its complexity and lack of harshness, and its source was from Guyanese molasses fermented for five days.

With my usual impeccable timing, I moved away from Canada at that exact time, and never managed (or seriously attempted) to pick up any of the Ministry of Rum Collection, since my attention was immediately taken up with agricoles and the European independents. However, one correspondent of mine, tongue in cheek as always, sent me an unidentified sample (“St. Lucia” was all the bottle said), and after tasting it blind, being quite impressed and writing up my notes, I asked him what it was. Obviously it was this one, a nine year old bottled at a rip-snorting 61.3%. And it really was something.

With my usual impeccable timing, I moved away from Canada at that exact time, and never managed (or seriously attempted) to pick up any of the Ministry of Rum Collection, since my attention was immediately taken up with agricoles and the European independents. However, one correspondent of mine, tongue in cheek as always, sent me an unidentified sample (“St. Lucia” was all the bottle said), and after tasting it blind, being quite impressed and writing up my notes, I asked him what it was. Obviously it was this one, a nine year old bottled at a rip-snorting 61.3%. And it really was something.

On the nose, the high ABV was hot but extremely well behaved, presenting wave after wave of the good stuff. It started off with rubber and pencil shavings, old cardboard in a dry cellar, some ashy kind of minerally smell, coffee, cumin and bitter chocolate…and then settling down and letting the rather shy fruits tiptoe forwards – raisins, some orange peel, peaches and prunes, all in balance and well integrated. No fault to find here – I was unsure whether a standard proof drink would have been quite as good (in fact, probably not). Throughout the whole exercise – I had the glass on the table with some others for a couple of hours – there was some light smoke and burnt wood, which fortunately stayed in the background and didn’t derail the experience.

As for the palate, wow – if gold could be a taste, that was what it was. Honey and burnt sugar, salty caramel all mixed up with flowers, more chocolate and the citrus peel. The tannins from the barrel began to be somewhat more assertive here, but never overbearing. In fact, the balance between these components was really well handled. With water, deep thrumming notes of molasses and anise shook the glass, leading to grapes, pineapple, acetone (just a little), aromatic tobacco and olives in brine; and throughout, the rum maintained a firm, rich profile that was quite excellent. Somewhere over the horizon, thunder was rolling. And as for the finish, here it stumbled a little on the line – long as it was, the tannics became too sharp; and while other closing hints remained firm (mostly molasses, caramel and brine plus maybe a prune or two) overall some of the tempering of one taste with another was lost.

But I must note that the rum is a damned good one. I think it’s a useful intro rum for those making a timorous foray into cask strength, and for those who wanted more from the Admiral Rodney or the 1931 series, this might be everything they were looking for from the island.

Some years ago I ran several of the standard proof St Lucia Distillers rums against each other, observing that while they were quite good, they also seemed to be missing a subtle something that might elevate their profile and quality, and allow them take their place with the better known Bajans, Jamaicans and Guyanese. As the rum world moved on, it is clear that in small, patient, incremental steps — perhaps they were channeling Nine Leaves — St. Lucia Distillers, the source of this rum, were upping the tempo, and it took a few European indies and one old salt from the US, to show what the potential of the island was, and is. St. Lucia may have been flying somewhat under the radar, but I’m here telling you that this is a lovely piece of work by any standard, admirable, affordable and — I certainly hope — still available.

(86/100)

Other notes

- Vendome is a company, not a type of still, and dates back to the first decade of the 1900s, building on experience (and customers) dating back as far as the 1870s when Hoffman, Ahlers & Co. were doing brisk business in Louisville (Kentucky).

- Aside from the eight St. Lucian rums in the portfolio, The “Hamilton Collection” includes Jamaican and Guyanese rums. The Hamilton 151 is specifically intended to be better than (not to supplant) the Lemon Hart 151 which was out of production at the time.

- Kudos, thanks and a huge hat-tip to Quazi4moto, who sent the sample. He was, you might remember, the gent who sent me the Charley’s J.B. white rum I enjoyed a few months ago.