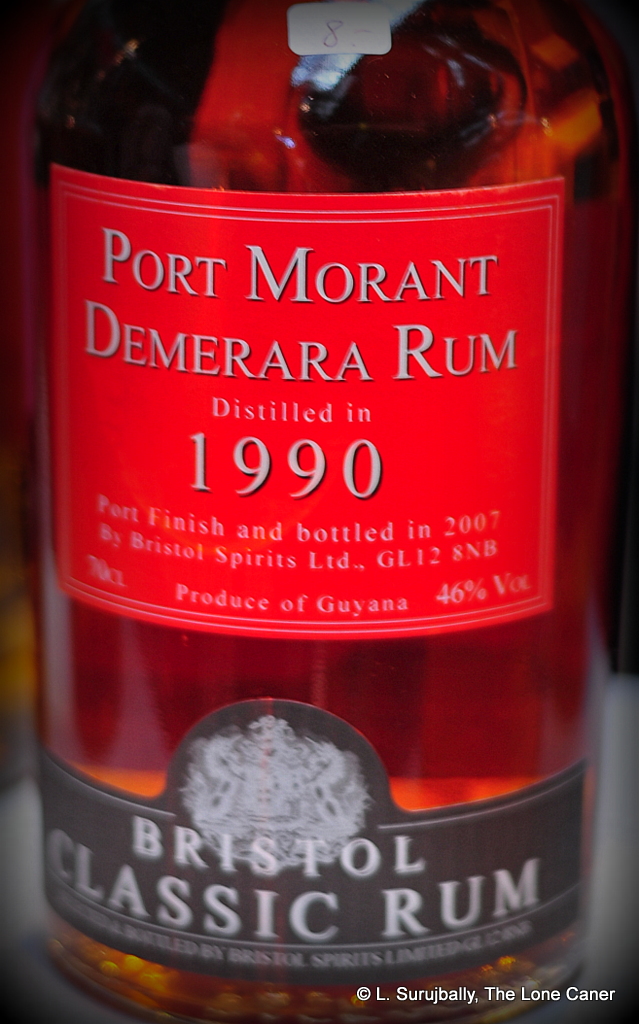

A love note from Bristol to lovers of Guyanese PM-still rums

Bristol Spirits is that independent bottler out of the UK which started life in 1993. Their barrel selection from the various countries around the Caribbean has created an enviable track record of limited bottlings; I’ll always have good memories of the Bristol Spirits PM 1980, and the subsequent editions of the 1990 and 1999 were rums I’ve been keeping an eye out for on the basis of that positive experience.

All of these were made, of course, using the Port Mourant distillate – in this particular instance they didn’t just age it between 1990 and 2007, but allowed it rest for the final two years in matured port pipes for an extra fillip of flavor. It sort of succeeded, it’s a great rum by any standard, and of course, they did continue their happy tradition of a funky, screaming fire-engine-red label slapped on to a standard barroom bottle. I just can’t pass these things by, honestly.

The PM 1990, a dark amber rum with ruby hints to it, derived from the famed wooden PM double pot still now held in DDL’s facilities at Diamond. It poured, sulky and heavy into the glass, and while it was tamed to a very accessible 46% (which is sort of de rigeur for many of the UK craft makers who seem determined not to lose a single sale by I dunno, issuing good rum at cask strength), the initial scents were impressive from the get-go. Wood, sweat, sap, brine, oak and smoke permeated the nose at once in thick waves. These are not always my favourite smells, but I used to say the same thing about plasticine and turpentine, so what do I know? It’s the way they come together and enhance the experience, that matters, anyway. And indeed, things mellowed out after some minutes, and the good stuff came dancing forward – raisins, Christmas cake, soy sauce, molasses, licorice and burnt sugar, all wrapped up in salty caramel and toffee, citrus rind (very faint) and chamomile (even fainter). Just a phenomenally rich nose, generous with promise.

It delivered on that promise very nicely, thank you very much. Warm and strong, some sweetness came forward here, with initial tastes of salt caramel, dulce de leche ice cream, and dark tea leaves. Quite full bodied to taste, no issues there for me at all – this thing was giving the PM 1980 some serious competition at a lesser price. The more familiar tastes of licorice, molasses-soaked brown sugar and musty leather came through, and after adding some water (didn’t really need to, but what the hell) the full cornucopia of everything that came before mushroomed on the tongue. Flowers, orange rind, licorice, smoke and some tannins, together with old polished leather and linseed oil, all full and delicious and not at all over-spicy and sharp. It’s fine rum, very fine indeed. The fade was shortish, not dry, quote smooth and added no new notes of consequences, but simply summarized all the preceding, exiting warmly and easily with caramel and toffee, anise, and then it was all gone and I was hastening to refill my glass.

Here I usually end with a philosophical statement, observations that come to mind, anything that can wrap things up in a neat bow. But truth to tell, in this case I don’t think I need to. Bristol Spirits have simply made a very good rum for the price (about a hundred bucks) and age (seventeen years). As such, it will be more accessible, more available and probably more appreciated than fiercely elemental, higher-proofed offerings costing much more. So in terms of value for money, this is one of those rums that I would recommend to anyone who wants to dip his or her toe into the realm of stronger, more complex, and also more focused high-end spirits. As long as your tastes run into dark and flavorful Guyanese rums, this one won’t disappoint.

(#229. 88/100)

Rumaniacs Review 004 | 0404

Rumaniacs Review 004 | 0404