Bristol Spirits – also known as Bristol Classic Rum — holds the distinction of being one of the earlier independent UK bottlers who was and remains specifically not a distillery or a whisky bottler, such as the ones which held sway in the 1980s and 1990s. While Gordon & MacPhail, A.D. Rattray, Cadenhead and a few other companies from Scotland occasionally amused themselves by issuing a rum, few took it seriously, and even the indie Italians like Samaroli and Moon Imports and Rum Nation took a while to get in on the act. Of course, the worm is turning and the situation is changing now with the rise of the New Brits, but that’s another story.

Bristol Spirits – also known as Bristol Classic Rum — holds the distinction of being one of the earlier independent UK bottlers who was and remains specifically not a distillery or a whisky bottler, such as the ones which held sway in the 1980s and 1990s. While Gordon & MacPhail, A.D. Rattray, Cadenhead and a few other companies from Scotland occasionally amused themselves by issuing a rum, few took it seriously, and even the indie Italians like Samaroli and Moon Imports and Rum Nation took a while to get in on the act. Of course, the worm is turning and the situation is changing now with the rise of the New Brits, but that’s another story.

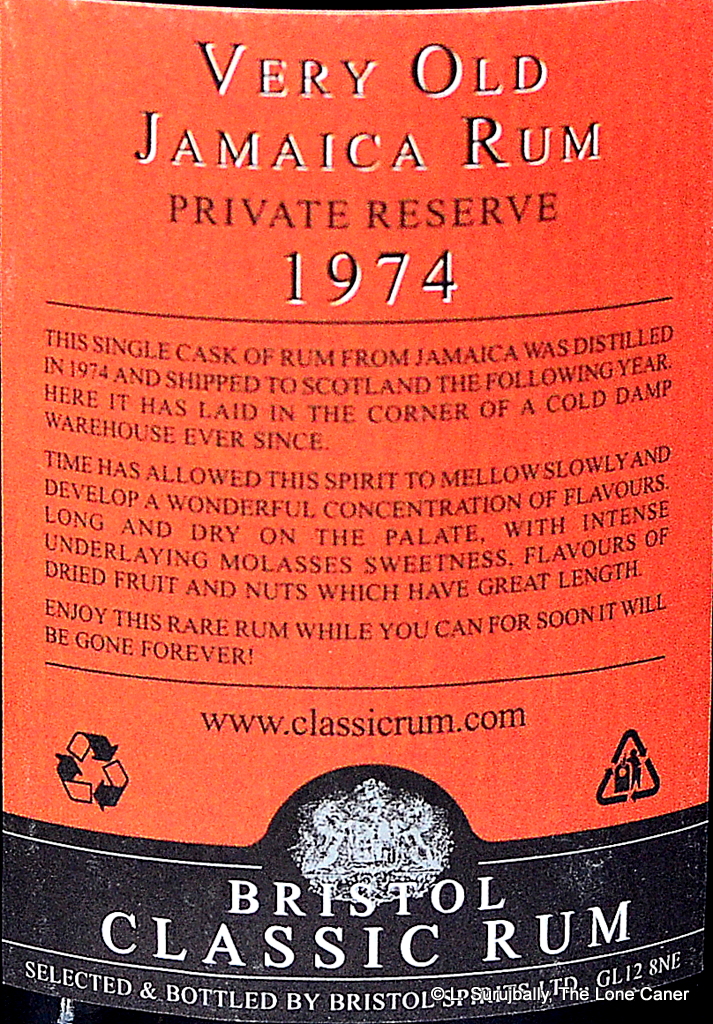

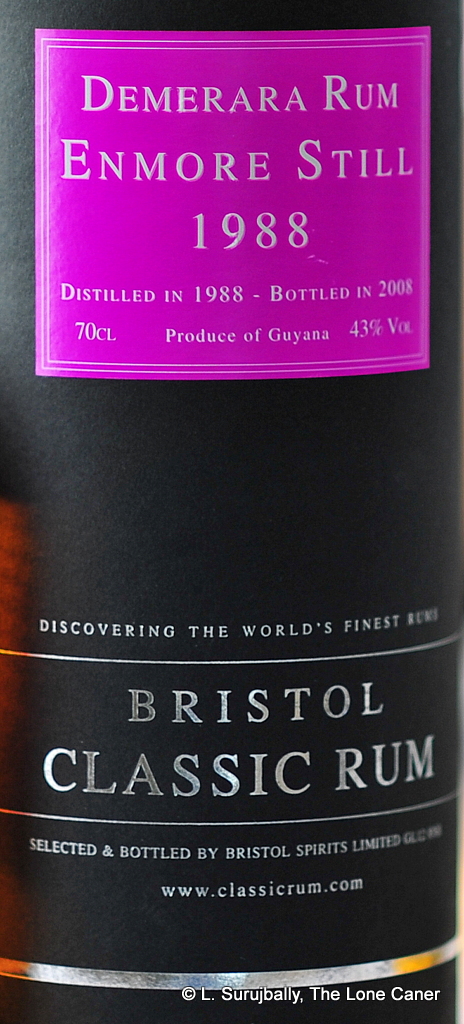

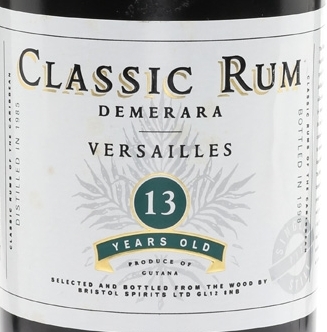

Bristol Spirits, unlike those old houses, focused on rum almost immediately as they were founded in 1993, and while their earlier bottlings are now the stuff of misty legend and tall tales, I can tell you of some releases which are now considered near-classics of the genre: the 1980 30YO Port Mourant, the 1974 34 YO Caroni, and the pair of Very Old Rums from 1974 (Jamaica, 30YO) and 1975 (Demerara, 35YO); plus, some would likely add the Rockley Still 26YO 1986 Sherry Finish. Gradually as the years wore on, John Barrett – who remains the managing director of the company and runs it personally with his son in law Simon Askey – branched off into barrel selection and ageing and does a brisk sideline in trading aged rums or laying down new stocks with other small indies or private clients, and occasionally dabbles in the blending game…more to assuage a creative itch and see what will happen, I sometimes think, than to make the final sale (Florent Beuchet of Compagnie des Indes has also gone down this path).

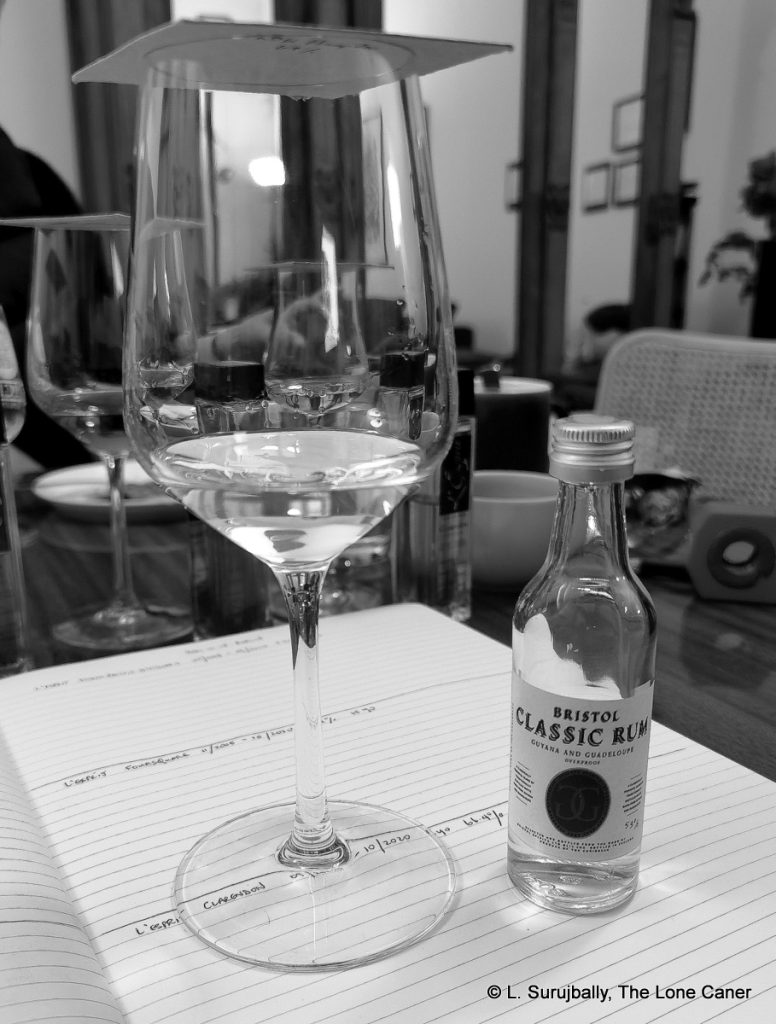

One of these blends which Bristol came up with is this interesting overproof bottled at 59% – unfortunately there’s very little I can tell you about the off-white product, since there is literally nothing online anywhere that speaks to it. The strength and that it comes from Guyana and Guadeloupe is all I know, though Simon tells me it was released around the late 1990s / 2000 (after which, in an interesting bit of trivia, JB soured on doing miniatures such as I had scored for this review) and the Guadeloupe component was likely Damoiseau (to be confirmed) – other than that, the still of the former, the distillery in the latter, the proportions, the ageing, the source material, the actual release date…all the usual stuff we now almost take for granted is missing from official records.

Well, that makes it a really blind tasting, so let’s get to it. Nose first, and it’s an odd one: charcoal, ashes and iodine, balanced by some brine, olives, figs and dates. The fruits take their time arriving, and when they do one can smell green apples and grapes, tart apricots, but little of the crisp grassiness of any kind of agricole influence. The Little Big Caner, who was lending his snoot, remarks on smells of old bubbling oil leaking from a hot engine block, a sort of black and treacly background which I interpret as thick blackstrap molasses, but more than that is hard to pin down, and there’s a kind of subtle bitterness permeating the nose which is a little disconcerting to say the least.

The taste is more forgiving and if it’s on the sharp and spicy side, at least there’s some flavour to go with it. Here there is a clean and briny texture, that channels some very ripe white fruits (pears, guavas, that kind of thing), with some lemon zest and green grapes hamming it up with watermelon and papaya and just a touch of peppermint. There some herbaceousness to the experience, yet all this dissipates to nothing at the close, which is briny, spicy, sweet and has sweet bell peppers as a closing note of grace.

The taste is more forgiving and if it’s on the sharp and spicy side, at least there’s some flavour to go with it. Here there is a clean and briny texture, that channels some very ripe white fruits (pears, guavas, that kind of thing), with some lemon zest and green grapes hamming it up with watermelon and papaya and just a touch of peppermint. There some herbaceousness to the experience, yet all this dissipates to nothing at the close, which is briny, spicy, sweet and has sweet bell peppers as a closing note of grace.

In assessing what it all comes down to, I must start with my observation that so far I have not found an agricole-molasses British-French-island-style blend that seriously enthuses me (and I remember Ocean’s Atlantic). The styles are too disparate to mesh properly (for my palate, anyway, though admittedly your mileage and mine will vary on this one) and the warm tawny wooden muskiness of Guyanese rum doesn’t do the ragtime real well with the bright clean grassy profiles of the French island cane juice agricoles.

And that is the case here. There are individual bits and pieces that are interesting and tasty – it’s just that they don’t come together and cohere well enough to make a statement. At the end, while this makes for a really good mixing rum (try it in a daiquiri, it’s quite decent there), as a rum to be tried on its own, I think you’ll find that the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

(#1023)(79/100) ⭐⭐⭐

Other notes

- The rum is a slightly pale yellow, almost white. The label blurb calls it a blend of white rums (on the left side) but below the logo of two intertwined Gs is a remark that they are “selected and bottled from the wood”, which implies at least some ageing. More cannot be said at this time.

- It was confirmed that John Barrett blended this himself. As soon as I get more information on the sources, I’ll update the post. Many thanks to Simon, who helped out a lot on short notice.

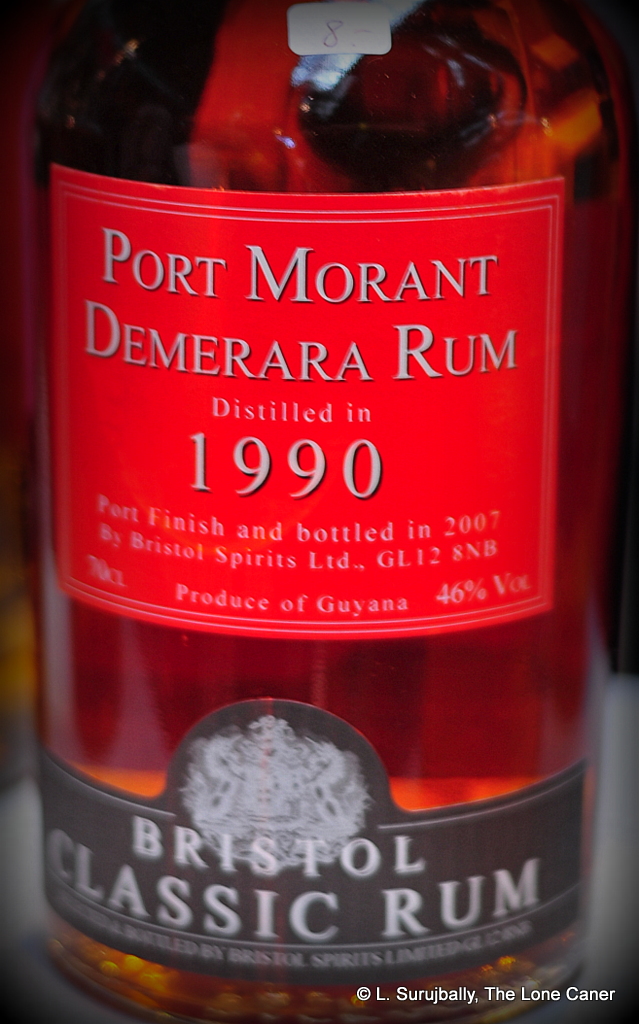

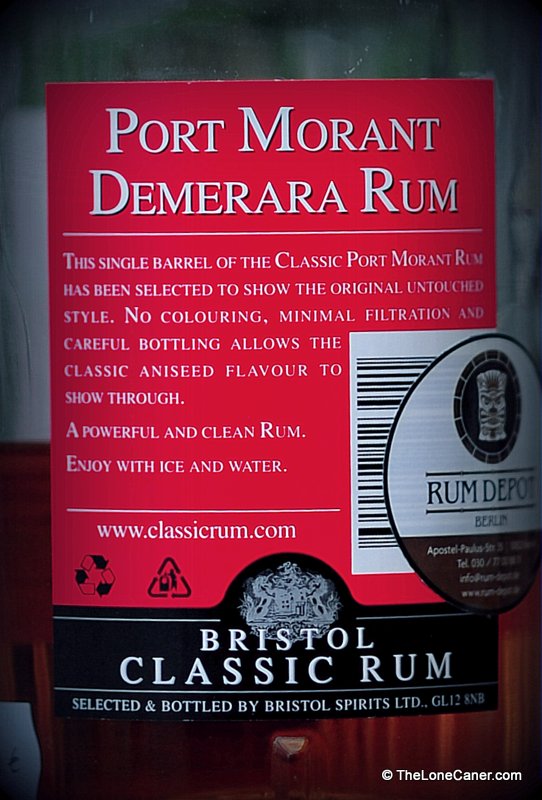

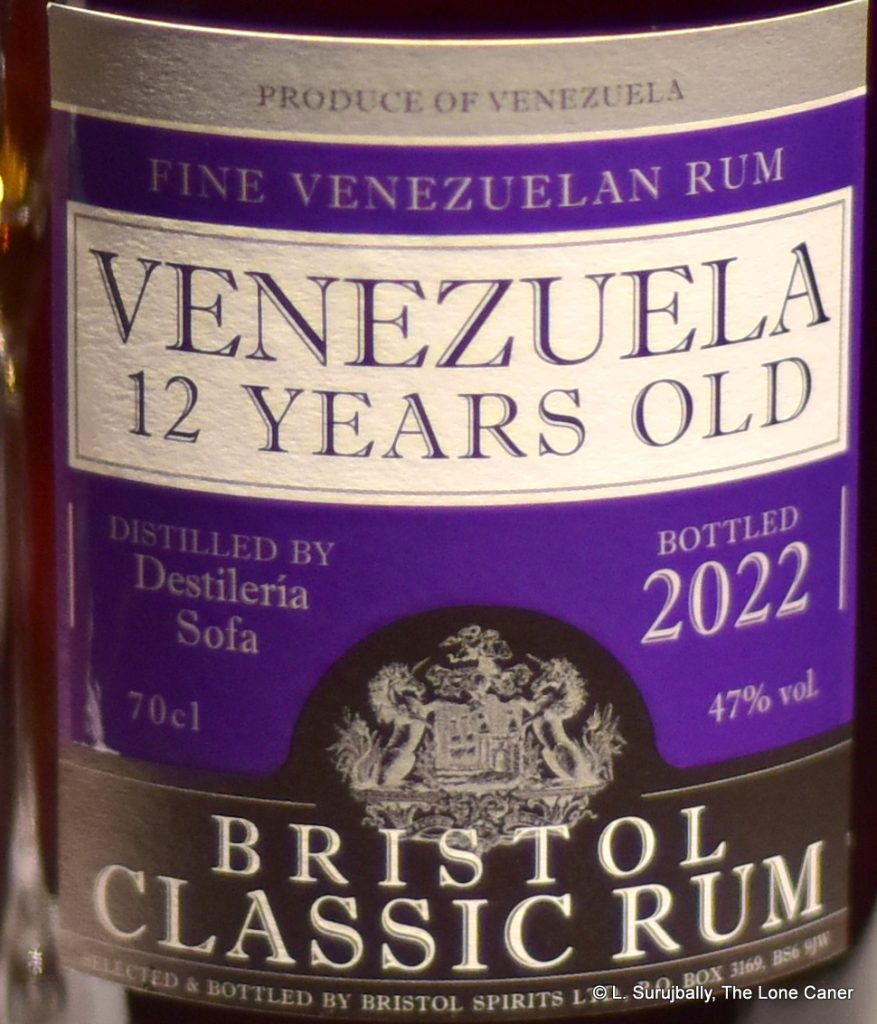

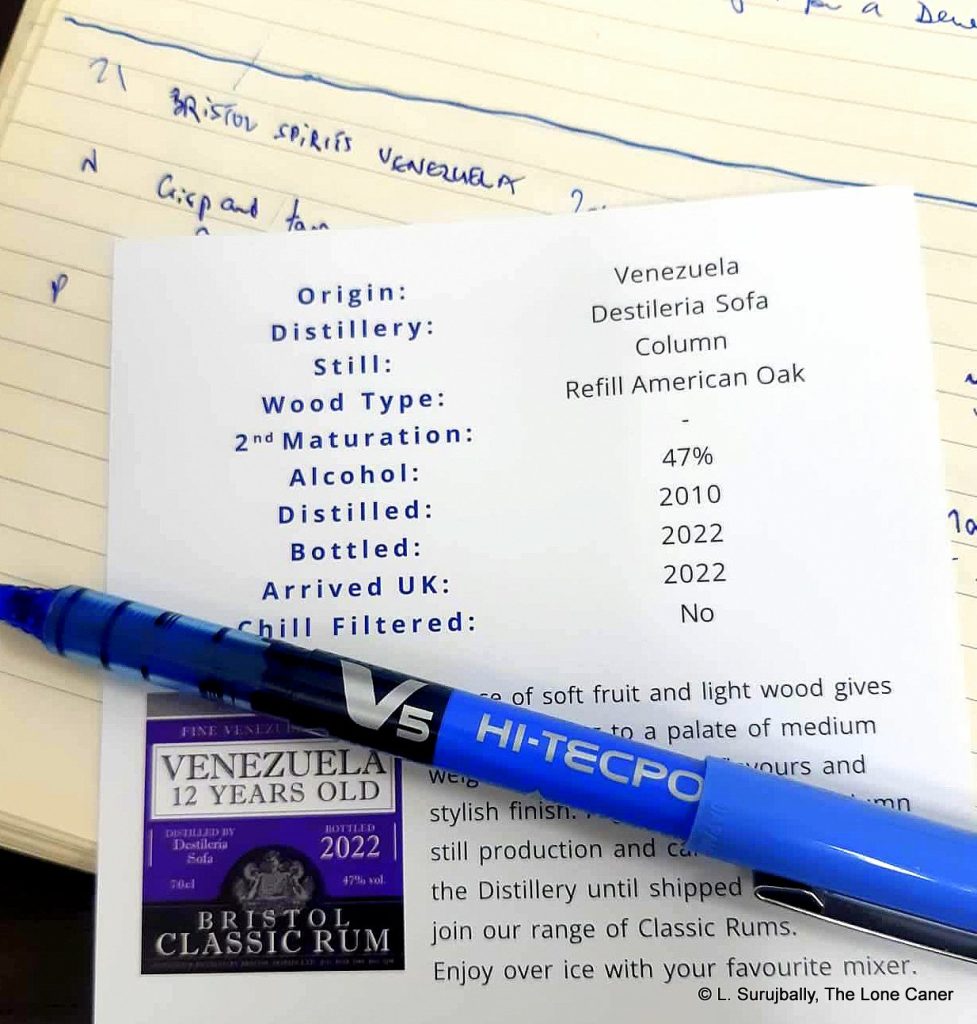

Bristol, I think, came pretty close with this relatively soft 46% Demerara. The easier strength may have been the right decision because it calmed down what would otherwise have been quite a seriously sharp and even bitter nose. That nose opened with rubber and plasticine and a hot glue gun smoking away on the freshly sanded wooden workbench. There were pencil shavings, a trace of oaky bitterness, caramel, toffee, vanilla and slowly a firm series of crisp fruity notes came to the fore: green apples, raisins, grapes, apples, pears, and then a surprisingly delicate herbal touch of thyme, mint, and basil.

Bristol, I think, came pretty close with this relatively soft 46% Demerara. The easier strength may have been the right decision because it calmed down what would otherwise have been quite a seriously sharp and even bitter nose. That nose opened with rubber and plasticine and a hot glue gun smoking away on the freshly sanded wooden workbench. There were pencil shavings, a trace of oaky bitterness, caramel, toffee, vanilla and slowly a firm series of crisp fruity notes came to the fore: green apples, raisins, grapes, apples, pears, and then a surprisingly delicate herbal touch of thyme, mint, and basil.

The brief technical blah is as follows: bottled by Bristol Spirits out of the UK from distillate left to age in Scotland for 26 years; a pot still product (I refer you to

The brief technical blah is as follows: bottled by Bristol Spirits out of the UK from distillate left to age in Scotland for 26 years; a pot still product (I refer you to