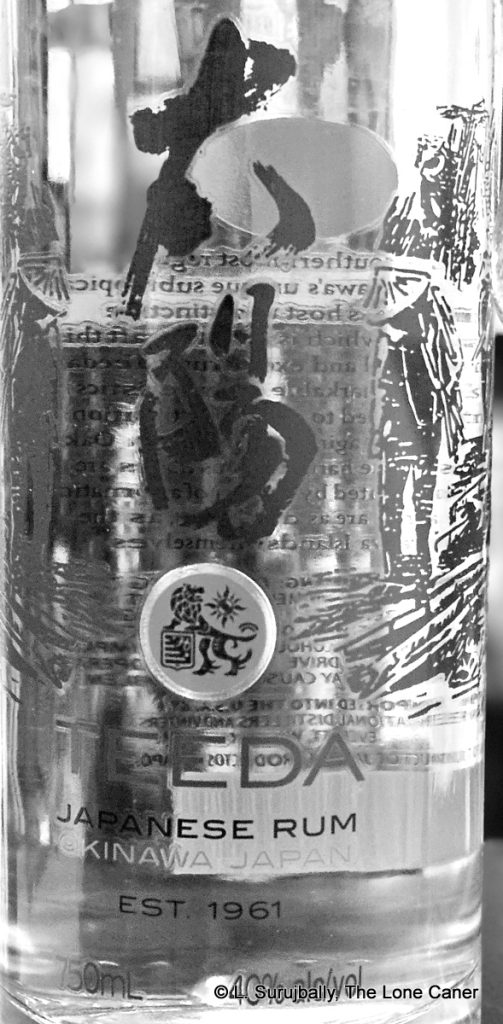

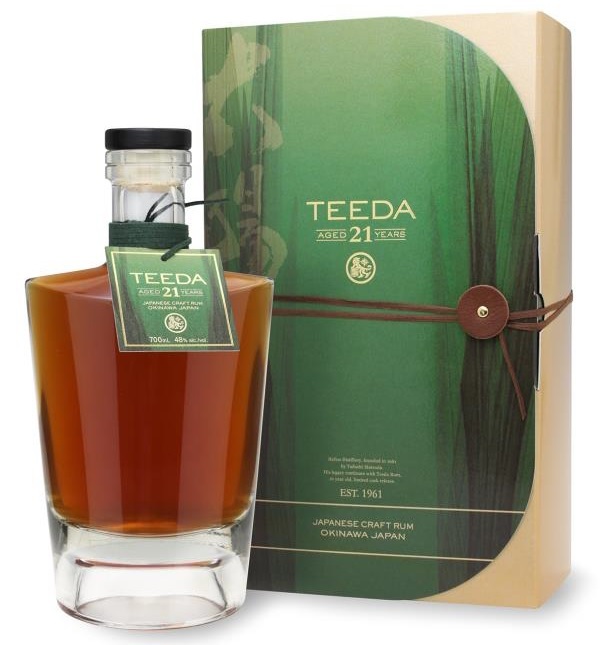

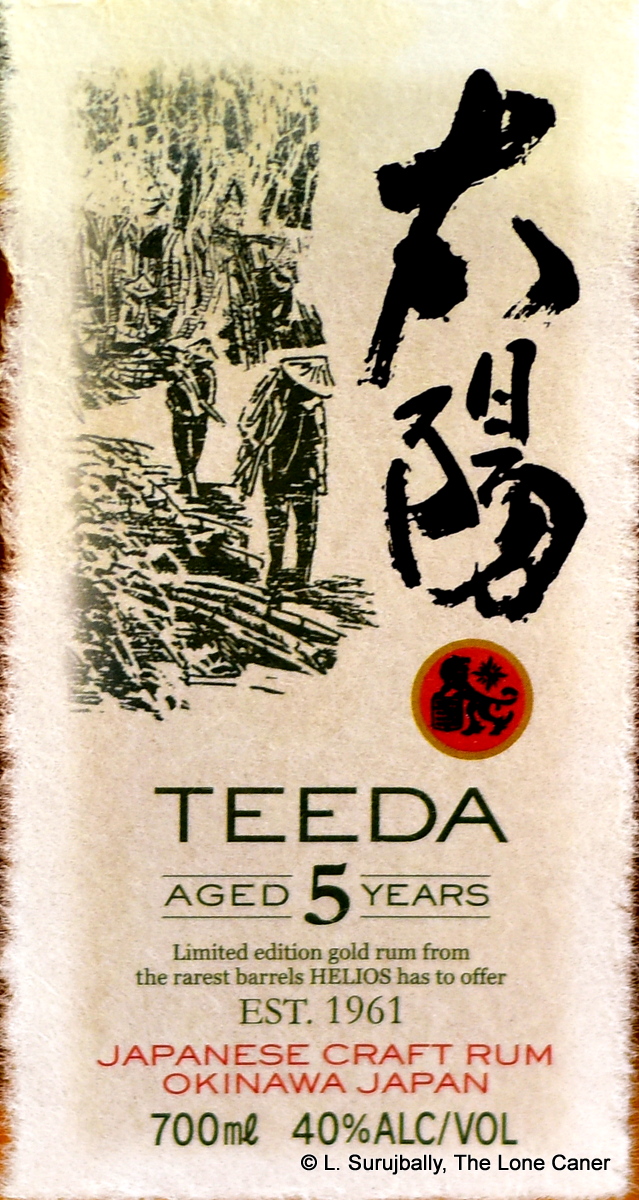

“Teeda” is a Japanese word meaning “sunshine”, which is a nice name considering that the distillery in Japan that makes it is called “Helios”. We have looked at several of Helios’s rums before this – the unaged Kiyomi white, the blended gold rum, the 5YO rum, and of course the pricey but very good 21 YO I just did a video review for last week. It is unusual that they have nothing in the midrange between 6 and 20 years of age, like most other distillers, but maybe they’re just laying down stocks, and the 21YO was something of an outlier.

The Okinawan Helios Distillery has been in the business since 1961 – it is supposedly the oldest such distillery in the country. Then, it was called Taiyou, and made cheap rum blends from sugar cane, both to sell to the occupying American forces, and to save rice for food and sake  production. They are probably better known in Japan for their awamoris, shochus and beers, but for our purposes, it’s the rums that excite attention.

production. They are probably better known in Japan for their awamoris, shochus and beers, but for our purposes, it’s the rums that excite attention.

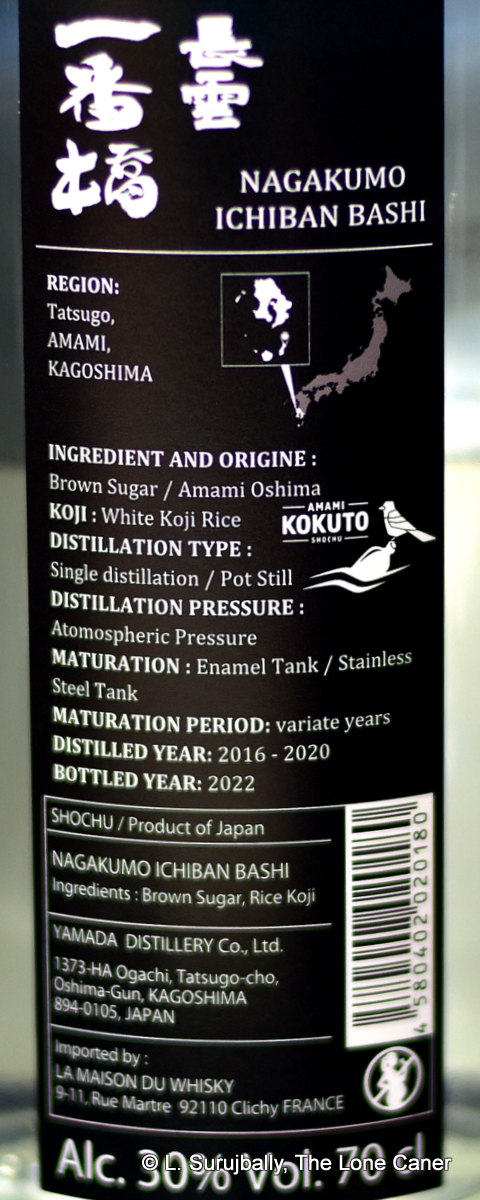

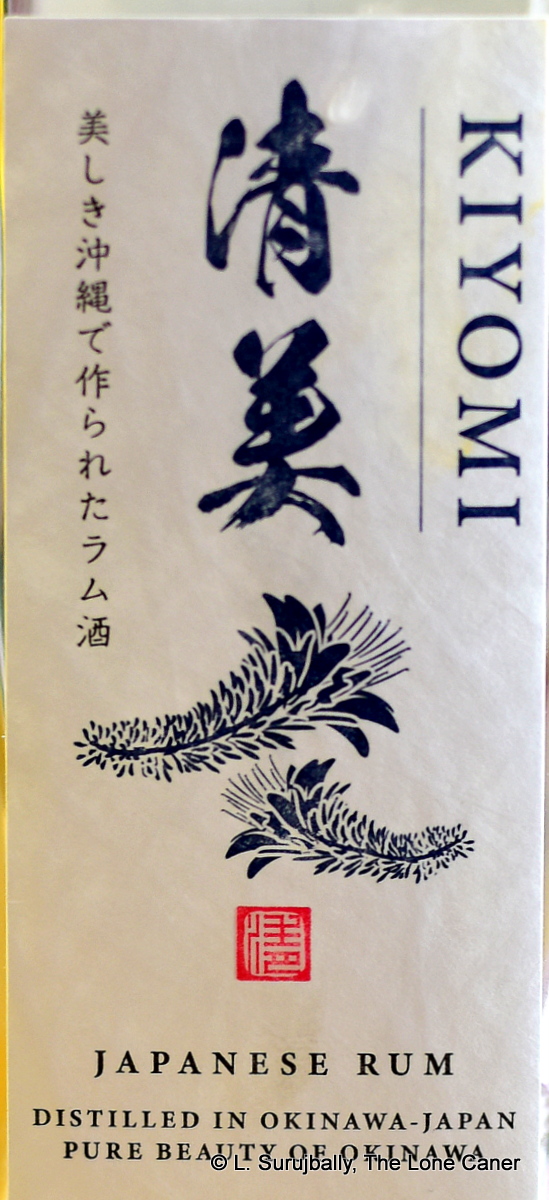

This one is a white issued at 40%, and is made from condensed sugar cane juice (the label refers to it as kokuto, or unrefined sugar, which is akin to panela in Mexico, or jaggery in India) – this is also used to make shochus in Japan 1, and it’s hardly surprising that Okinawans would also use it to make this distilled spirit. It’s run through a pot still and aged a little, although I can’t find any indication how long – let’s assume about a year for now, and you’ll permit me a private muttering grumble about how I still have to trawl around too much for this rather minimal information.

That out of the way, let’s get right to it. The nose is all dusty paper, cardboard, peeling wallpaper, with a strong scent of rotting potatoes after you peel them. This is not entirely bad, but one has to admit, it’s unusual. Fortunately, there’s also vegetable soup with extra beef broth and a pimento or two, which then gradually dissolves into scents of sweet soya sauce and figs, dates and fleshy fruits. This is all then balanced off with some citrus that cuts the strong scents that precede it. It is quite a lively nose for something at living room strength…though it must be said, this sucker will take some getting used to.

Tasting it makes for a better experience, much better – the rum turns a little sweet, with fewer potatoes (although the scent and taste persist). Again, you can taste sweet soya, vanilla, smoke, celery, prunes, figs and some lemongrass-infused soup, and yes, that pimento is still there. It all leads to a comfortable finish which sums things up with some soup, salt, celery and prunes, not a lot else.

Tasting it makes for a better experience, much better – the rum turns a little sweet, with fewer potatoes (although the scent and taste persist). Again, you can taste sweet soya, vanilla, smoke, celery, prunes, figs and some lemongrass-infused soup, and yes, that pimento is still there. It all leads to a comfortable finish which sums things up with some soup, salt, celery and prunes, not a lot else.

I can’t entirely rid myself of the feeling that the tum (like the 21YO) used some koji mould to start the fermentation, as well as yeast. There’s a meatiness in some Japanese rums (my traumatic encounter with Seven Seas attests to the peculiarity of the profile) which points in this direction, and while the overall quality can’t be denied, it is something of a connoisseur’s rum – and I mean that not to be snobby, but to illustrate that if you have had a ton of rums and are looking for something unique, this one comes close.

But if you’re only now starting out, then it’s probably best to skip it for now. Because that nose and taste, so peculiar and unique, those are simultaneously sleek and buggy in the details, like a software update rushed out too quick. In short, be careful with it.

(#1106)(81/100) ⭐⭐⭐

Other notes

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages (

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages ( The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

I’ve never been completely clear as to what effect a resting period in neutral-impact tanks would actually have on a rum – perhaps smoothen it out a bit and take the edge off the rough and sharp straight-off-the-still heart cuts. What is clear is that here, both the time and the reduction gentle the spirit down without completely losing what makes an unaged white worth checking out. Take the nose: it was relatively mild at 40%, but retained a brief memory of its original ferocity, reeking of wet soot, iodine, brine, black olives and cornbread. A few additional nosings spread out over time reveal more delicate notes of thyme, mint, cinnamon mingling nicely with a background of sugar water, sliced cucumbers in salt and vinegar, and watermelon juice. It sure started like it was out to lunch, but developed very nicely over time, and the initial sniff should not make one throw it out just because it seems a bit off.

I’ve never been completely clear as to what effect a resting period in neutral-impact tanks would actually have on a rum – perhaps smoothen it out a bit and take the edge off the rough and sharp straight-off-the-still heart cuts. What is clear is that here, both the time and the reduction gentle the spirit down without completely losing what makes an unaged white worth checking out. Take the nose: it was relatively mild at 40%, but retained a brief memory of its original ferocity, reeking of wet soot, iodine, brine, black olives and cornbread. A few additional nosings spread out over time reveal more delicate notes of thyme, mint, cinnamon mingling nicely with a background of sugar water, sliced cucumbers in salt and vinegar, and watermelon juice. It sure started like it was out to lunch, but developed very nicely over time, and the initial sniff should not make one throw it out just because it seems a bit off.

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything.

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything.

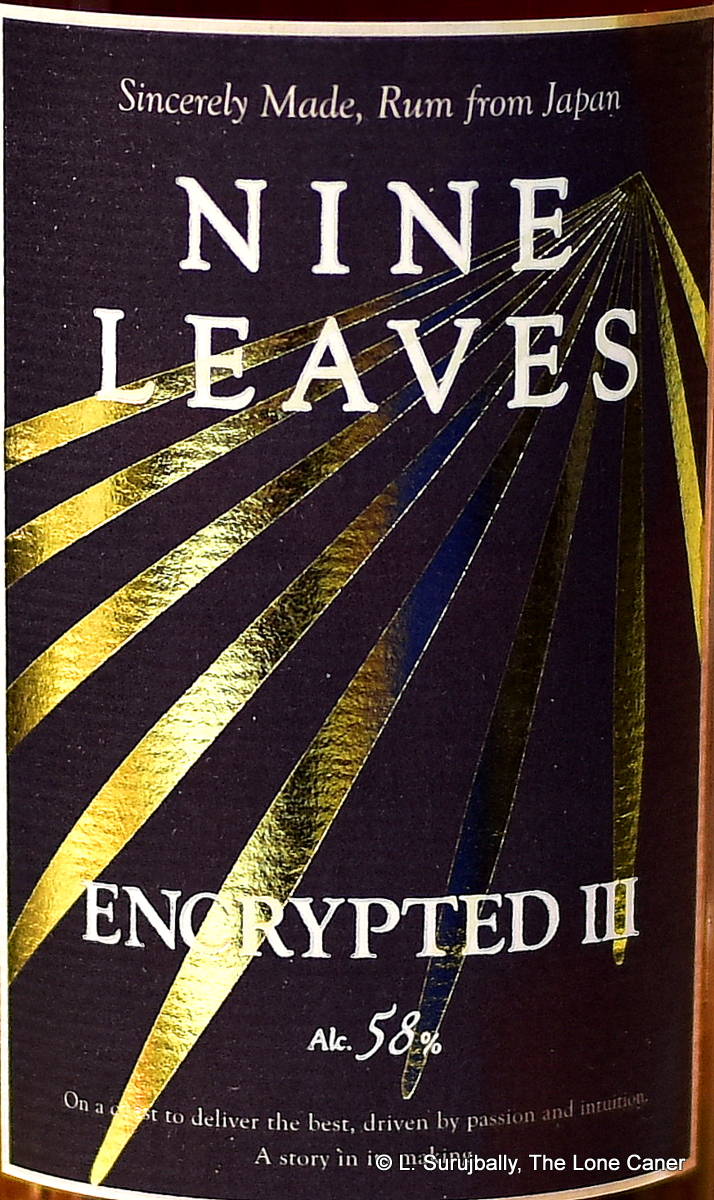

The nose rather interestingly presented hints of a funky kind of fruitiness at the beginning (like a low rent Jamaican, perhaps), while the characteristic clarity and crisp individualism of the aromas such as the other Nine Leaves rums possessed, remained. It was musky and sweet, had some zesty citrus notes, fresh apples, pears and overall had a pleasing clarity about it. Plus there were baking spices as well – nutmeg and cumin and those rounded out the profile quite well.

The nose rather interestingly presented hints of a funky kind of fruitiness at the beginning (like a low rent Jamaican, perhaps), while the characteristic clarity and crisp individualism of the aromas such as the other Nine Leaves rums possessed, remained. It was musky and sweet, had some zesty citrus notes, fresh apples, pears and overall had a pleasing clarity about it. Plus there were baking spices as well – nutmeg and cumin and those rounded out the profile quite well.