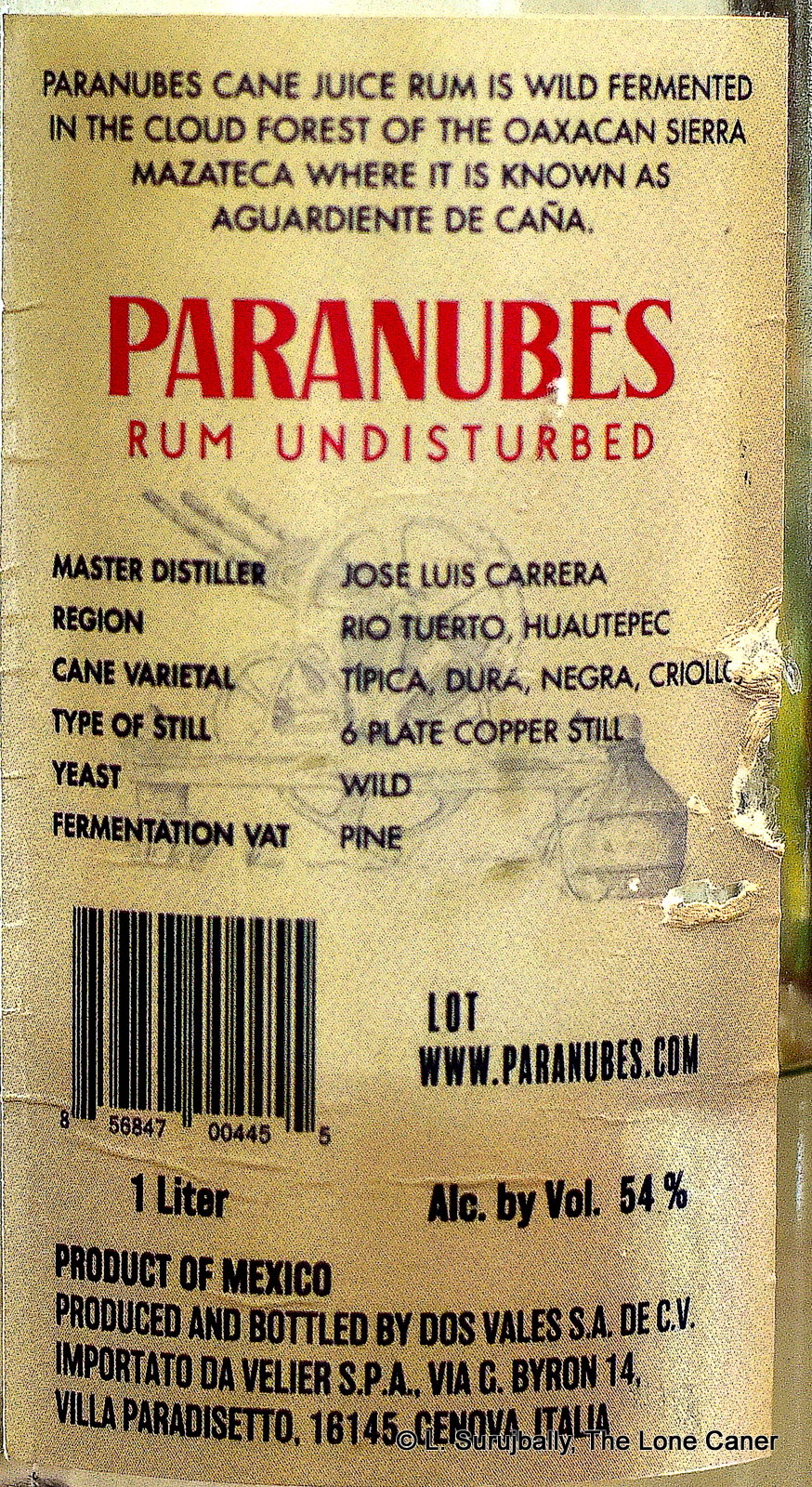

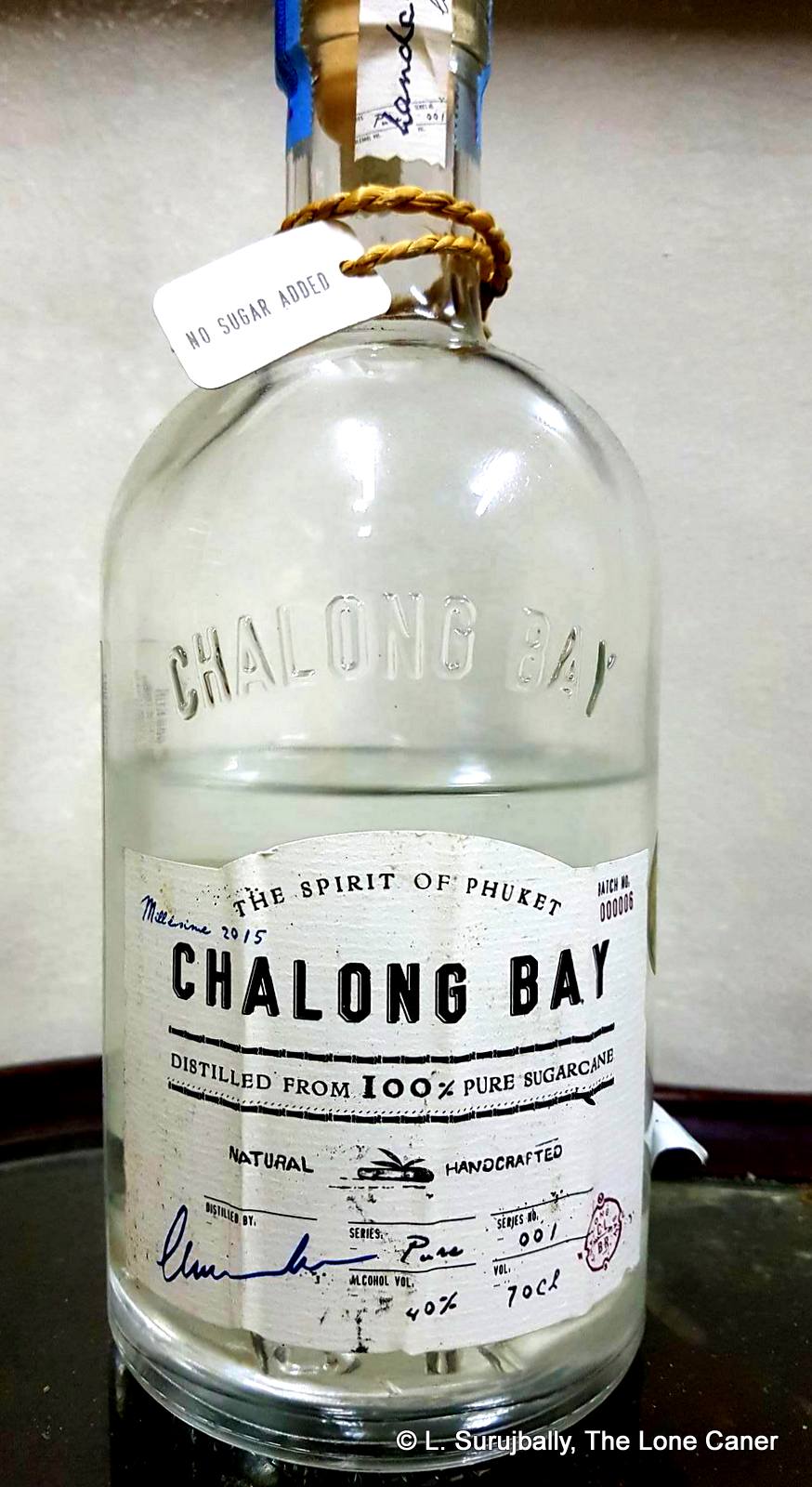

White rhums – or blancs – were not products I paid much attention to back in the day, but over the last five years they have continually risen in my estimation, and now I consider them one of the key building blocks of the entire category. Not the lightly-aged, blandly filtered and softly murmuring Spanish-style cocktail staples, you understand – those I regard with relative indifference. No, I mean stuff like the Mexican Paranubes, the Haitian Le Rocher, the Guyanese Superior High Wine, Japanese Nine Leaves Clear, Tahitian Mana’o White or the Surinamese Toucan White, to say nothing of the new crop out of Asia – Samai, Issan, Laodi, Sampan, Chalong Bay…

What elevates these blancs and all their cousins above the regular run of whites is the way they often maintain a solid connection to the distillate of origin and the land from which they came. They are usually unaged and unfiltered, commonly around 50% or better. Sometimes they’re raw and pestilential and shockingly rude, at other times they’re almost placid, hiding their bright tastes and clear profiles behind a wall of easy and deceptive complexity that takes time to tease out properly (and for both reasons causes them to be occasionally under-appreciated, I think).

Which brings me to the 55% ABV Habitation Saint-Étienne (HSE) Rhum Blanc Agricole that was distilled in Martinique in 2016 and bottled in 2018 (it rested in steel tanks for the duration and can therefore be seen as unaged). We haven’t talked about HSE for a while, but that doesn’t mean that the Martinique brand has been resting on its laurels, because it continues to produce much good rhum – all AOC compliant – and even taken the whites in a new direction. In this case, perhaps channelling Velier’s Uitvlugt East Field 30 from all those years ago, they selected a special type of sugar cane (canne d’or says the bottle, or “gold cane”, varietal designation R570) not just from their sugar estate in the middle of Martinique, but from a specific part of it – the Verger and Coulon plots of land, issued as a rhum they call Parcellaire #1. So it’s a sort of micro version of HSE as a whole, showcasing a very small part of its terroire.

Aside from HSE, Longueteau, or the new kid on the island block — A1710 and their white La Perle — such atomized drilldowns into smaller subunits of an estate are almost unknown…but they are intriguing to say the least (even though it may all just be cool marketing – I like to think otherwise). Fortunately the way it smelled and tasted skated over such concerns. The nose, for example, was quite fragrant, starting off with slightly rotten fruits (bananas), rubber, sawdust, set to a background of soft wax candle, all very restrained. Overall it was a little sweet and relaxed, and as it opened, additional notes of nuts, cereals, almonds and nougat came forward. There was also a hint of olives, brine, pineapple, sweet green peas and ripe oranges in an excellent melange that combined themselves very well, without any single aspect being particularly dominant.

Blanc agricoles’ tastes are usually quite distinct, showing variation only in the details. This one was slightly different — very smooth, very light, the usual herbs and light citrus and grasses starting things off, just less crisp than one might be expecting. This seemed to be kind of nothing-in particular, but hold on a bit — the other, more complex flavours started to creep out. Dill, sugar water, olive oil, cucumbers, watermelon, light pimentos and gherkins, all sweet enough not to be off-putting, salty/sour enough for some character. I thought it was really quite tasty, giving aged offerings from the same house some serious competition, and finishing things off with a fade that provided last memories of sweet sugar water, light delicate notes of cumin and watermelon and papaya.

Does that all work? Are the specific plots of origin really that clear? I suggest that as a showcase for such a tiny bit of land, for the general rum drinker, not really. The differences between the regular run of blancs from HSE and this one can be chalked up to miniscule divergences deriving from batch variation rather than anything so refined. Admittedly though, I’m not a professional sommelier, and lack the experience such people bring to sensing gradations of wine hailing from neighboring vinyards in France – so someone with a more finely tuned snoot may take more away from this than I did.

But I liked it. I liked it a lot. Above, I wrote that really good whites are either cheerfully rude or deceptively polite: this one tilts slightly more towards the latter while still remembering its objurgatory antecedents. It’s a enormously drinkable dram, near perfect strength, with wonderfully delicate and strong tastes mixing up both sweet and salt in a terrific white rhum. You could drink it alone or mix it as you please, and you’d enjoy it either way, with nothing but a nod of appreciation for what HSE have achieved here with such seeming effortlessness. And for its price? This thing may just be an undiscovered steal.

(#580)(86/100)

Other notes

The Habitation Saint-Étienne is located almost dead centre in the middle of Martinique. Although in existence since the early 1800s, its modern history properly began when it was purchased in 1882 by Amédée Aubéry, an energetic man who combined the sugar factory with a small distillery, and set up a rail line to transport cane more efficiently (even though oxen and people that pulled the railcars, not locomotives). In 1909, the property came into the possession of the Simonnet family who kept it until its decline at the end of the 1980s. The estate was then taken over in 1994 by Yves and José Hayot — owners, it will be recalled, of the Simon distillery, as well as Clement — who relaunched the Saint-Étienne brand using Simon’s creole stills.

Anyway, here’s what it was like. The nose of the Ilha da Madeira fell somewhere in the middle of the line separating a bored “meh” from a more disbelieving “holy-crap!”. It was a light melange of a playful sprite-like aroma mixed in with more serious brine and olives, a little sweet, and delicate – flowers, sugar water, grass, pears, guavas, mint, some marzipan. You could sense something darker underneath – cigarette tar, acetones – but these never came forward, and were content to be hinted at, not driven home with a sledge. Not really a brother to that fierce Jamaican brawler, more like a cousin, a closer relative to the

Anyway, here’s what it was like. The nose of the Ilha da Madeira fell somewhere in the middle of the line separating a bored “meh” from a more disbelieving “holy-crap!”. It was a light melange of a playful sprite-like aroma mixed in with more serious brine and olives, a little sweet, and delicate – flowers, sugar water, grass, pears, guavas, mint, some marzipan. You could sense something darker underneath – cigarette tar, acetones – but these never came forward, and were content to be hinted at, not driven home with a sledge. Not really a brother to that fierce Jamaican brawler, more like a cousin, a closer relative to the  In the last decade, several major divides have fissured the rum world in ways that would have seemed inconceivable in the early 2000s: these were and are cask strength (or full-proof) versus “standard proof” (40-43%); pure rums that are unadded-to versus those that have additives or are spiced up; tropical ageing against continental; blended rums versus single barrel expressions – and for the purpose of this review, the development and emergence of unmessed-with, unfiltered, unaged white rums, which in the French West Indies are called

In the last decade, several major divides have fissured the rum world in ways that would have seemed inconceivable in the early 2000s: these were and are cask strength (or full-proof) versus “standard proof” (40-43%); pure rums that are unadded-to versus those that have additives or are spiced up; tropical ageing against continental; blended rums versus single barrel expressions – and for the purpose of this review, the development and emergence of unmessed-with, unfiltered, unaged white rums, which in the French West Indies are called

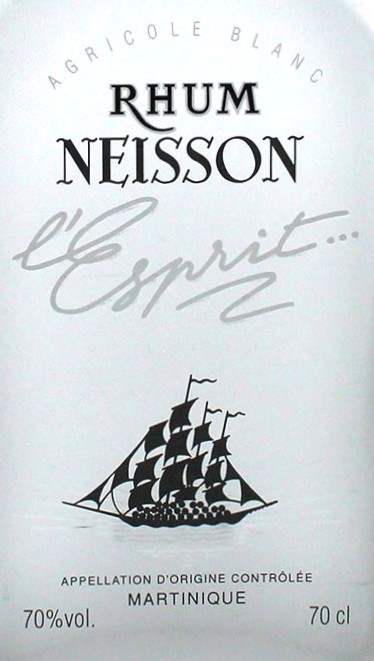

Well, that out of the way, let me walk you through the profile. Nose first: what was immediately evident is that it adhered to all the markers of a crisp agricole. It gave off of light grassy notes, apples gone off the slightest bit, watermelon, very light citrus and flowers. Then it sat back for some minutes, before surging forward with more: olives in brine, watermelon juice, sugar cane sap, peaches, tobacco and a sly hint of herbs like dill and cardamom.

Well, that out of the way, let me walk you through the profile. Nose first: what was immediately evident is that it adhered to all the markers of a crisp agricole. It gave off of light grassy notes, apples gone off the slightest bit, watermelon, very light citrus and flowers. Then it sat back for some minutes, before surging forward with more: olives in brine, watermelon juice, sugar cane sap, peaches, tobacco and a sly hint of herbs like dill and cardamom.

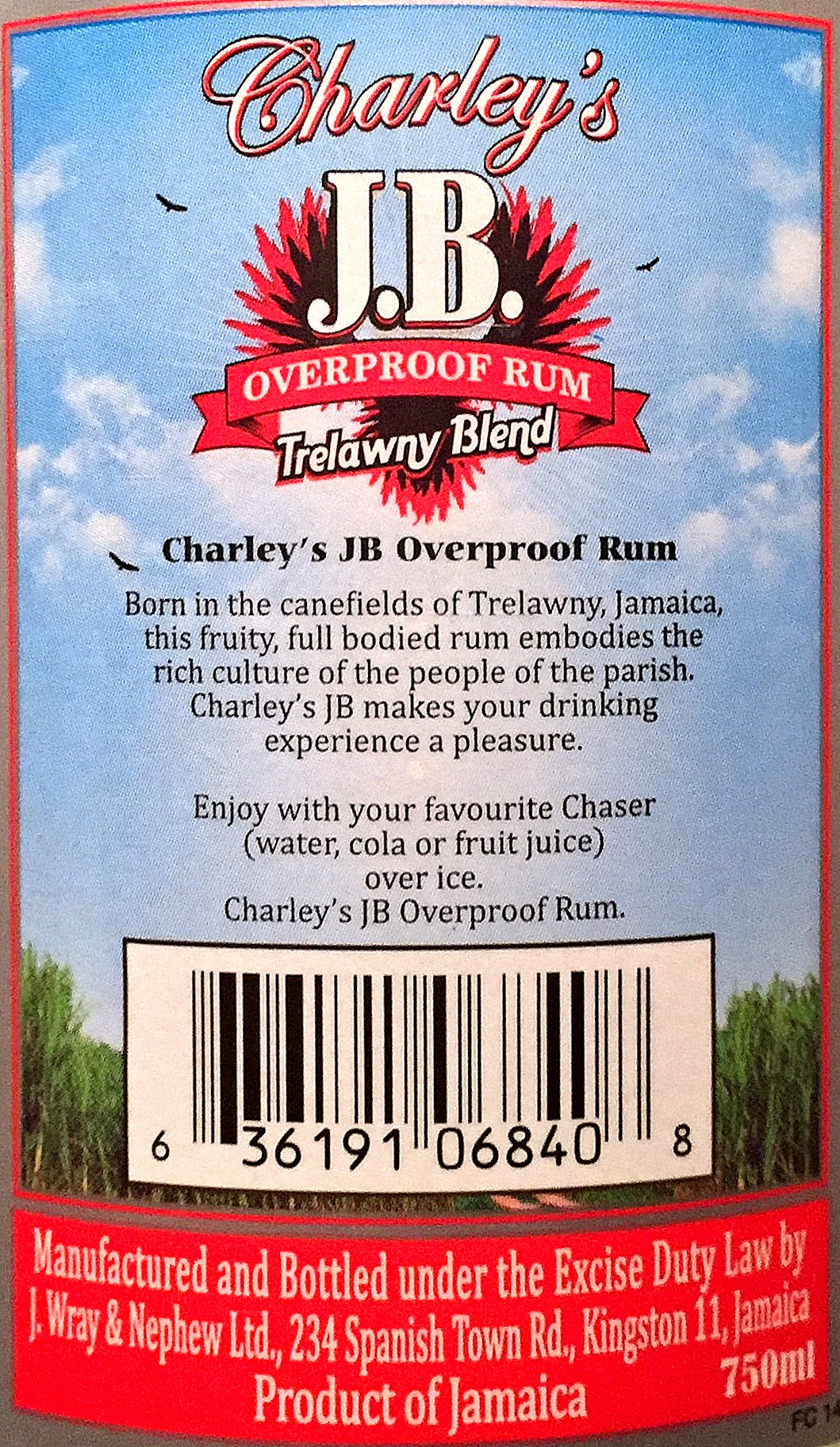

Unaged rums take some getting used to because they are raw from the barrel and therefore the rounding out and mellowing of the profile which ageing imparts, is not a factor. That means all the jagged edges, dirt, warts and everything, remain. Here that was evident after a single sip: it was sharp and fierce, with the licorice notes subsumed into dirtier flavours of salt beef, brine, olives and garlic pork (seriously!). It took some time for other aspects to come forward – gherkins, leather, flowers and varnish – and even then it was not until another half hour had elapsed that crisper acidic notes like unripe apples and thai lime leaves (I get those to buy in the local market), were noticeable. Plus some vanilla – where on earth did that come from? It all led to a long, duty, dry finish that provided yet more: sweet, sugary, sweet-and-salt soy sauce in a clear soup. Damn but this was a heady, complex piece of work. I liked it a lot, really.

Unaged rums take some getting used to because they are raw from the barrel and therefore the rounding out and mellowing of the profile which ageing imparts, is not a factor. That means all the jagged edges, dirt, warts and everything, remain. Here that was evident after a single sip: it was sharp and fierce, with the licorice notes subsumed into dirtier flavours of salt beef, brine, olives and garlic pork (seriously!). It took some time for other aspects to come forward – gherkins, leather, flowers and varnish – and even then it was not until another half hour had elapsed that crisper acidic notes like unripe apples and thai lime leaves (I get those to buy in the local market), were noticeable. Plus some vanilla – where on earth did that come from? It all led to a long, duty, dry finish that provided yet more: sweet, sugary, sweet-and-salt soy sauce in a clear soup. Damn but this was a heady, complex piece of work. I liked it a lot, really.

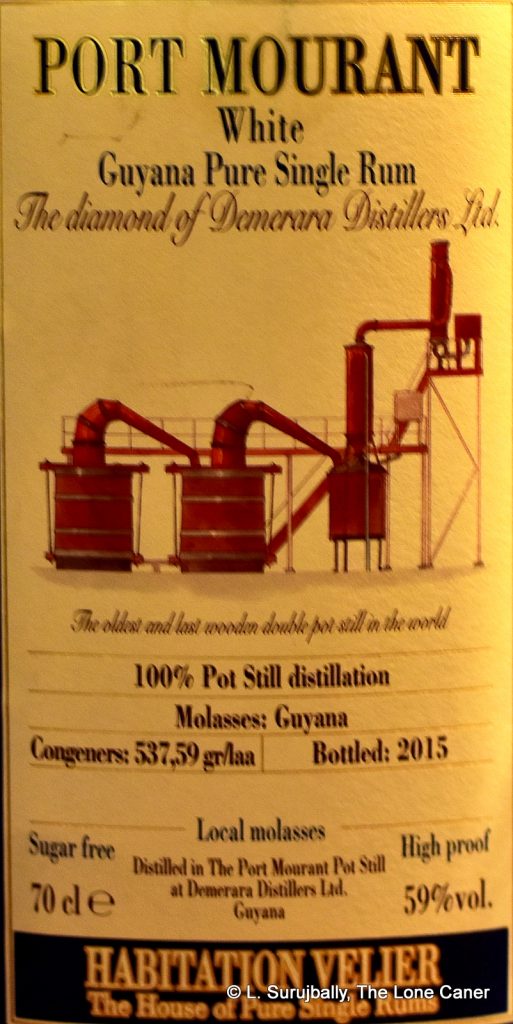

Sometimes a rum gives you a really great snooting experience, and then it falls on its behind when you taste it – the aromas are not translated well to the flavour on the palate. Not here. In the tasting, much of the richness of the nose remains, but is transformed into something just as interesting, perhaps even more complex. It’s warm, not hot or bitchy (46.5% will do that for you), remarkably easy to sip, and yes, the plasticine, glue, salt, olives, mezcal, soup and soya are there. If you wait a while, all this gives way to a lighter, finer, crisper series of flavours – unsweetened chocolate, swank, carrots(!!), pears, white guavas, light florals, and a light touch of herbs (lemon grass, dill, that kind of thing). It starts to falter after being left to stand by itself, the briny portion of the profile disappears and it gets a little bubble-gum sweet, and the finish is a little short – though still extraordinarily rich for that strength – but as it exits you’re getting a summary of all that went before…herbs, sugars, olives, veggies and a vague mineral tang. Overall, it’s quite an experience, truly, and quite tamed – the lower strength works for it, I think.

Sometimes a rum gives you a really great snooting experience, and then it falls on its behind when you taste it – the aromas are not translated well to the flavour on the palate. Not here. In the tasting, much of the richness of the nose remains, but is transformed into something just as interesting, perhaps even more complex. It’s warm, not hot or bitchy (46.5% will do that for you), remarkably easy to sip, and yes, the plasticine, glue, salt, olives, mezcal, soup and soya are there. If you wait a while, all this gives way to a lighter, finer, crisper series of flavours – unsweetened chocolate, swank, carrots(!!), pears, white guavas, light florals, and a light touch of herbs (lemon grass, dill, that kind of thing). It starts to falter after being left to stand by itself, the briny portion of the profile disappears and it gets a little bubble-gum sweet, and the finish is a little short – though still extraordinarily rich for that strength – but as it exits you’re getting a summary of all that went before…herbs, sugars, olives, veggies and a vague mineral tang. Overall, it’s quite an experience, truly, and quite tamed – the lower strength works for it, I think.

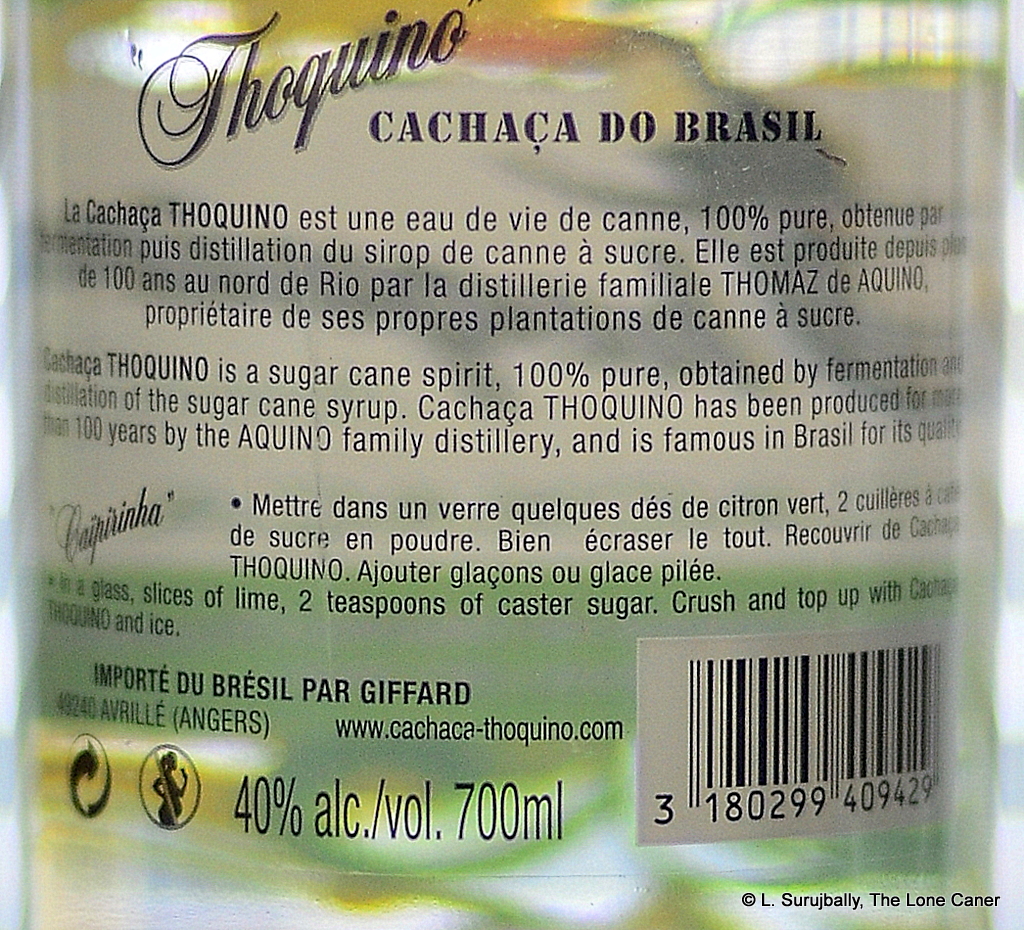

Never mind. Quite aside from these biographical details, I’m always on the lookout for interesting white rums, and so made it a point to check out the Prata just to see how well it fared. Which was, for a 42% rested-but-not-aged pot still rum, not shabby at all, if not quite as feral or in-your-face as some of the French island

Never mind. Quite aside from these biographical details, I’m always on the lookout for interesting white rums, and so made it a point to check out the Prata just to see how well it fared. Which was, for a 42% rested-but-not-aged pot still rum, not shabby at all, if not quite as feral or in-your-face as some of the French island

See, while furious aggression

See, while furious aggression