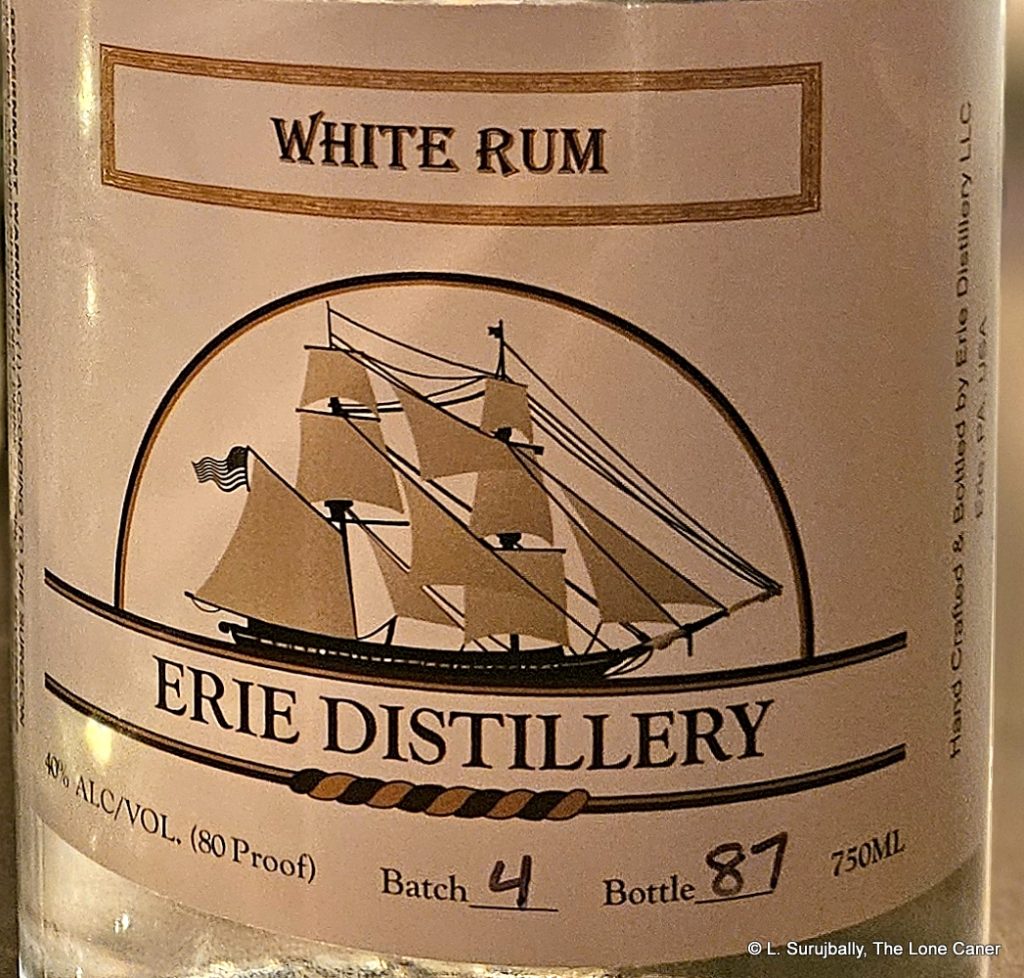

Recently, a rum that crossed my path was the US-made Erie White Rum, which is made in NE Pennsylvania by the Erie distillery, founded in 2019 by a Mr. David Harkness. This is a gentleman who has been playing with distillation since 2007, and he seems to be something of a cheerful mad scientist, experimenting with products as varied as limoncello, moonshines, whiskey, white rum, and vodka. In that way, he reminds me of some of the New Australians, who also go all over the map with their products so as to sell to just about anything to anyone who might want a drink.

Recently, a rum that crossed my path was the US-made Erie White Rum, which is made in NE Pennsylvania by the Erie distillery, founded in 2019 by a Mr. David Harkness. This is a gentleman who has been playing with distillation since 2007, and he seems to be something of a cheerful mad scientist, experimenting with products as varied as limoncello, moonshines, whiskey, white rum, and vodka. In that way, he reminds me of some of the New Australians, who also go all over the map with their products so as to sell to just about anything to anyone who might want a drink.

That said, it’s unclear what the production process is and what the white rum is all about. The company website rather unhelpfully doesn’t mention where the molasses comes from (assuming that’s the base material for the rum – I think it’s likely); or what kind of still they have, or whether rum is truly unaged or aged and then filtered… you know, all the usual stuff you’d think anyone who is paying attention to the rum world would provide as a minimum. On FB and some news articles, however, I found that it’s a 8-inch-diameter, 9-foot-tall, 9-plate single-column stainless steel still that can pump out 95% ABV vodka, so, okay. The company seems to concentrate on whiskey more than anything else — rum, as is not unusual in the USA, being something of an afterthought.

Bottled at an inoffensive 40%, what we get is a nose that is at first blush watery and as mild as milquetoast, that takes the better part of fifteen minutes to open up just enough so we can sense other things. Those are, for the most part some lime scented sugar water, a touch of pickled cabbages (think kimchi), and as time wears on, more assertive lemon wedges can be smelled more distinctly. I had this one glass on the go for an hour, and let me tell you, what I’m writing here sounds simple, but it really did take that long to tease them out.

No help on the palate, I’m afraid. The rum’s mouthfeel was thin and scratchy, channeling the scrawny ferocity of an underfed alley cat. It tasted of sugar water, lime zest (or lemon – it’s close), more sour cabbage, cucumbers and white pepper, and no real fruitiness to speak of beyond some papaya and watery pears — and people, I’m reaching for that. No surprises, the finish was gone in a flash, with little to remember it by.

No help on the palate, I’m afraid. The rum’s mouthfeel was thin and scratchy, channeling the scrawny ferocity of an underfed alley cat. It tasted of sugar water, lime zest (or lemon – it’s close), more sour cabbage, cucumbers and white pepper, and no real fruitiness to speak of beyond some papaya and watery pears — and people, I’m reaching for that. No surprises, the finish was gone in a flash, with little to remember it by.

Overall, it reminds me more of lemon flavoured vodka than a rum, there’s so little to set it apart. I am at a loss to explain that citrus-forward flavour, unless they did not clean out the still properly after making a batch of limoncello (in that way, it reminded me of El Destilado’s Mexican Aguardiente de Panela and the carryover of pine notes). That citrus note is fine, up to a point, but that’s all there really is and the other aromas and flavours are so meek that it comes off as milder than water, and about as interesting as a blank sheet of paper.

Think of all those small and passionate distillers in countries around the world — South Africa, rural Mexico, the clairins of Haiti, grogues of Cabo Verde, or the tiny distilleries in Laos, Viet Nam, Cambodia, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, to name but a few — and meditate on the difference between their successes or even their magnificent failures, and this relatively indifferent product. When I see so many small micros from everywhere and anywhere try like hell to innovate, make something startling and new, all while adhering to tried and true traditions and wring serious magic from small stills held together by Bata flip flops, baling wire and some superglue, you can understand my impatience with the slapdash work Erie has put out here.

Sorry, but it’s a pass for me.

(#1133)(72/100) ⭐⭐½

Other notes

Opinion

People think I enioy writing snarky reviews of rums that (on occasion) they themselves might like, made by small local distilleries which some believe should be supported as they get their sh*t up to scratch. Admittedly, low-rent, indifferently-made rums are fun to eviscerate and taking the language for a spin is occasionally enjoyable, but the truth is somewhat more nuanced.

For one, much as I believe that harsh criticism sometimes just has to be made, I don’t like taking apart the efforts of some new enterprise that’s employing people and trying to survive. Also, as an advocate for the spirit, I know it’s not always possible to make good hooch right out of the gate, much as I might want them to do better, so I do try to be optimistic and cut such joints some slack.

But, if you’ve been playing around with distillation for over a decade before starting a commercial enterprise, I would expect that you know what you’re doing (think of Robert Greaves of Mhoba, Keri Algar of Carabita, or Yoshi Takeuchi of Nine Leaves, as examples). I dislike subpar work tossed off just to round out the spirits portfolio and the “good ‘nuff” mentality that presupposes any rum bottled at 40% can find its legs and its market with a minimum of effort.

And I don’t care overmuch for brands that put completely anonymous fare out the door, tell you almost nothing about it and hope sales will allow them to get better over time, when it’s clear no real thought went into crafting a decent rum in the first place – so, they went in with a hope and prayer and we have to subsidize improvement while they figure things out? That’s a hard bottle to sell, to me.

Company Bio

Company Bio