Bottled history. Nothing more, nothing less.

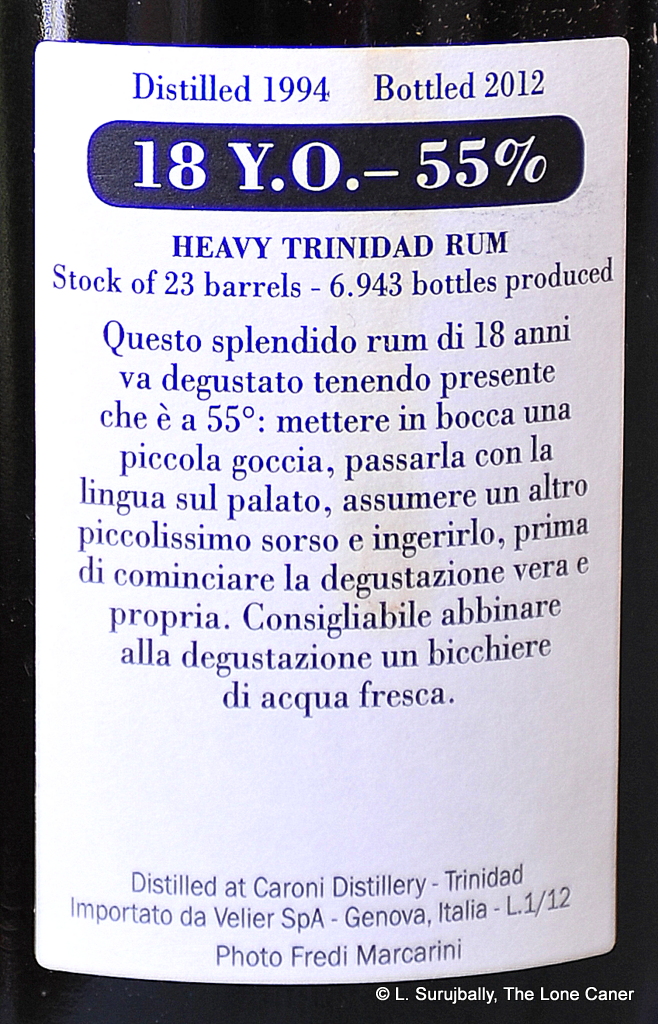

“The heart’s memory eliminates the bad and magnifies the good,” remarked Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and I remembered that bit of wisdom before embarking on our tryst with this rum. And to ensure that my long anticipation for the Tot wasn’t bending my feeble mind (I bought the bottle 2014, and tasted it for the first time almost a full year later) I tempered my judgement by trying it three times, with the Skeldon 1973 32 year old, BBR 1977 36 year old, a Velier Caroni and the Samaroli Barbados 1986. Just to be sure I wasn’t getting too enthusiastic you understand. I had to be sure. I do these things so you don’t have to.

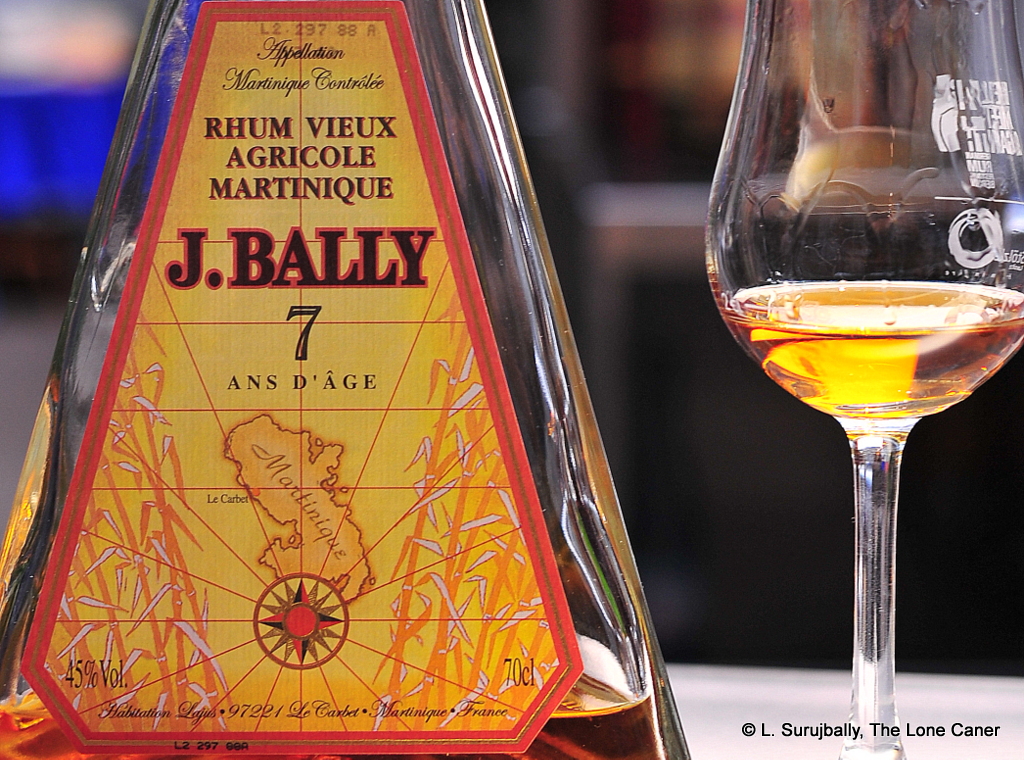

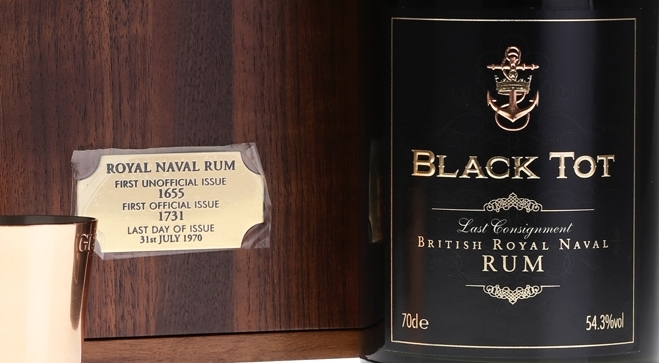

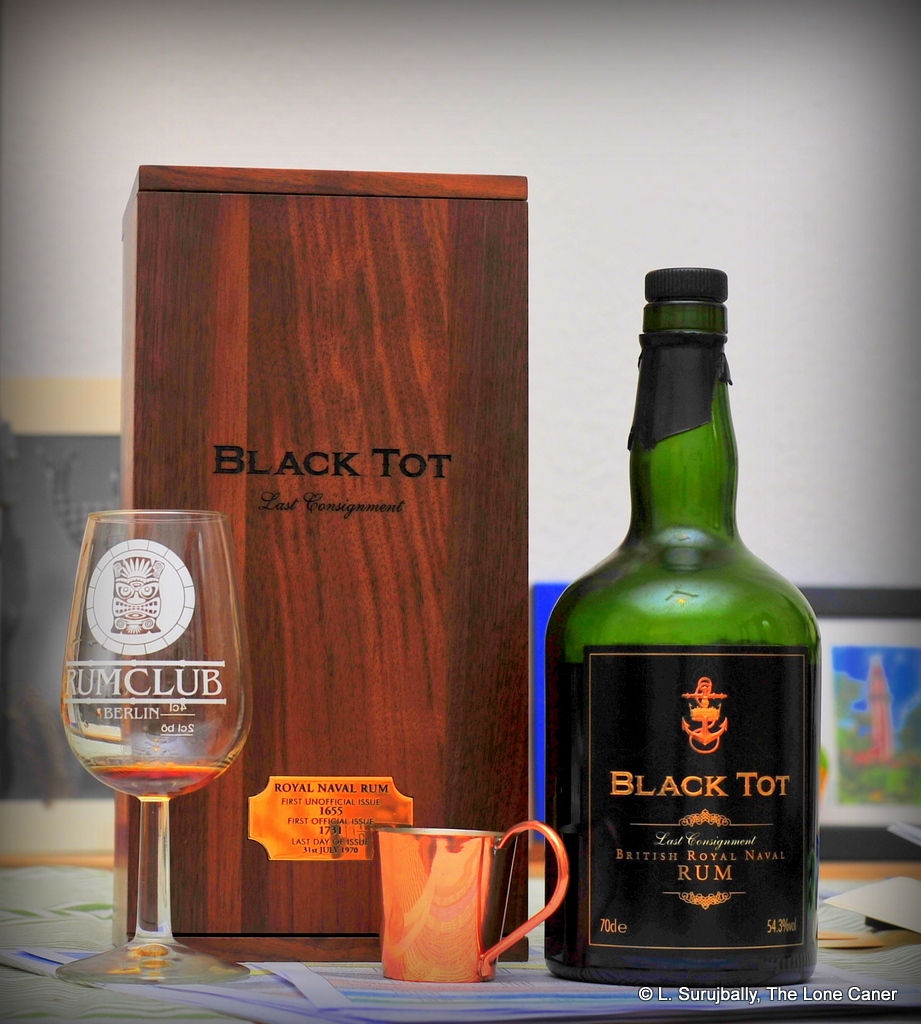

As much as the G&M Longpond 1941, St James 1885 or the J. Bally 1929, to name a few, the near-legendary Black Tot Last Consignment is one of the unicorns of the rum world. I’m not entirely convinced it should be so – many craft makers issue releases in lots of less than a thousand bottles, while some 7,000 bottles of this are in existence (or were). Nor is it truly on par with some of the other exceptional rums I’ve tried…the reason people are really willing to shell out a thousand bucks, is that whiff of unique naval pedigree, the semi-mystical aura of true historical heritage. A rum that was stored for forty years (not aged, stored) in stone flagons, and then married and bottled and sold, with a marketing programme that would have turned the rum into one of the absolute must-haves of our little world…if only it wasn’t quite so damned expensive.

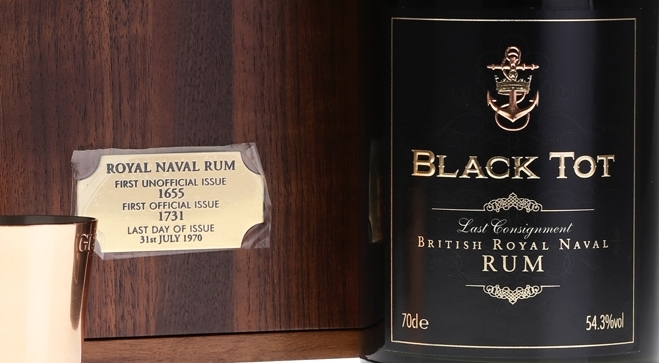

I don’t make these points to be snarky. After all, when you taste it, what you are getting is a 1960s rum and that by itself is pretty nifty. But there’s an odd dearth of hard information about the Tot that would help an average drinking Joe to evaluate it (assuming said Joe had the coin). About all you know going in is that it come from British Royal Navy stocks left over after the final rum ration was issued to the Jolly Jack Tars on Black Tot Day (31st July, 1970 for the few among you who don’t weep into your glasses every year on that date), and that it was released in 2010 on the same day. No notes on the rum’s true ageing or its precise components are readily available. According to lore, it supposedly contains rums from Barbados, Guyana (of course), Trinidad, and a little Jamaica, combining the dark, licorice notes of Mudland, the vanillas and tars of the Trinis and that dunderesque whiffy funk of the Jamaicans. And, the writer in me wants to add, the fierce calypso revelry of them all. Complete with mauby, cookup, doubles, rice and peas, pepperpot and jerk chicken.

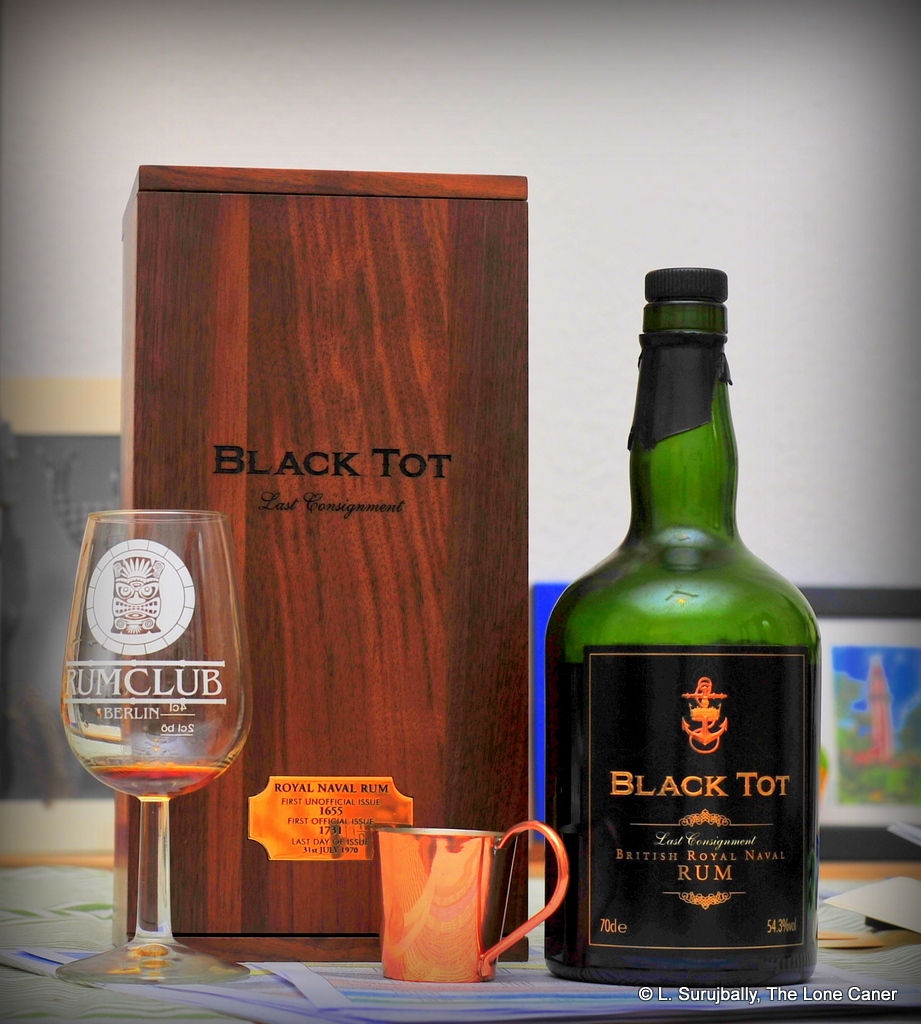

All that aside, the rum’s presentation is exceptional. A wooden box of dark wood (walnut? oak?). A booklet written by Dave Broom on the background to the rum. A copper plated tot container. A tot ration card facsimile. And a bottle whose cork was covered with a hard, brittle wax sealant that Gregers, Cornelius and Henrik laughed themselves silly watching me try to cut off. The bottle itself was a stubby barroom style bottle with a good cork. No fault to find on the appearance, at all. Believe me, we were all raring to try this one.

The aromas first: at 54.3%, I expected more sharpness than the Tot exhibited, and enjoyed the deep and warm nose. Initially, anise and slightly chocolate-infused fumes billowed out of our glasses in well controlled balance. Cardboard, musty hay, caramel and some tar and tobacco juice (maybe that was the Trinis speaking up?) followed swiftly. The official literature suggests that the Jamaican part of the blend was minimal, because sailors didn’t care for it, but what little there was exerted quite a pull: dunder and a vaguely bitter, grassy kind of funk was extremely noticeable. Here was a rum, however, that rewarded patience, so it was good that our conversation was long and lively and far-reaching. Minutes later, further scents of brine and olives emerged, taking their turn on the stage before being replaced in their turn by prunes, black ripe cherries, leavened with sharper oak tannins, and then molasses, some caramel, smoke, and then (oddly enough), some ginger and dried smoked sausages snuck in there. It was very good…very strong with what we could term traditional flavours. Still, not much new ground was broken here. It was the overall experience that was good, not the originality.

Good thing the palate exceeded the nose. Here the strength came into its own – the Tot was a borderline heavy rum, almost mahogany-dark, quite heated on the tongue, with wave after wave of rich dark unsweetened chocolate, molasses, brown sugar, oak deftly kept in check. Thick meaty flavours (yeah, there were those smoked deli meats again). It was a bit dry, nothing to spoil its lusciousness. We put down our glasses, talked rum some more, and when we tried it again, we noted some salty, creamy stuff (an aggressive brie mixing it up with red peppers stuffed with cheese in olive oil, was the image that persisted in my mind). Nuts, rye bread, some coffee. And underlying it all was the mustiness of an old second hand bookstore straight out of a gothic novel. I enjoyed it quite a bit. I thought the finish failed a little – it was dry, quite long, so no complaints on that score – it just added little more to the party than the guests we had already seen. Smoke, tannins, aromatic tobacco, some molasses again, a little vegetal stuff, that was about it. Leaving aside what I knew about it (or discovered later), had I tasted it blind I would have felt it was a rather young rum (sub-ten-year-old), with some aged components thrown in as part of the blend (but very well done, mind).

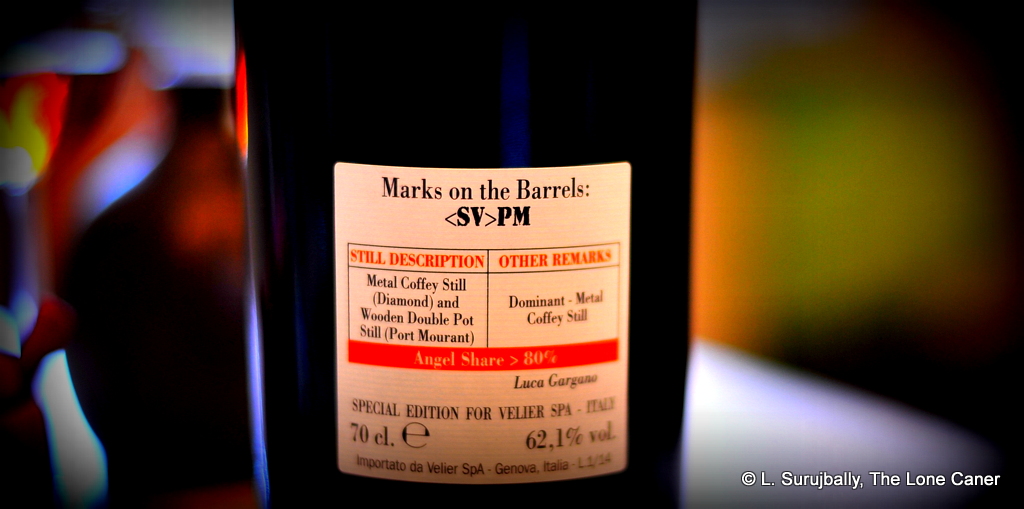

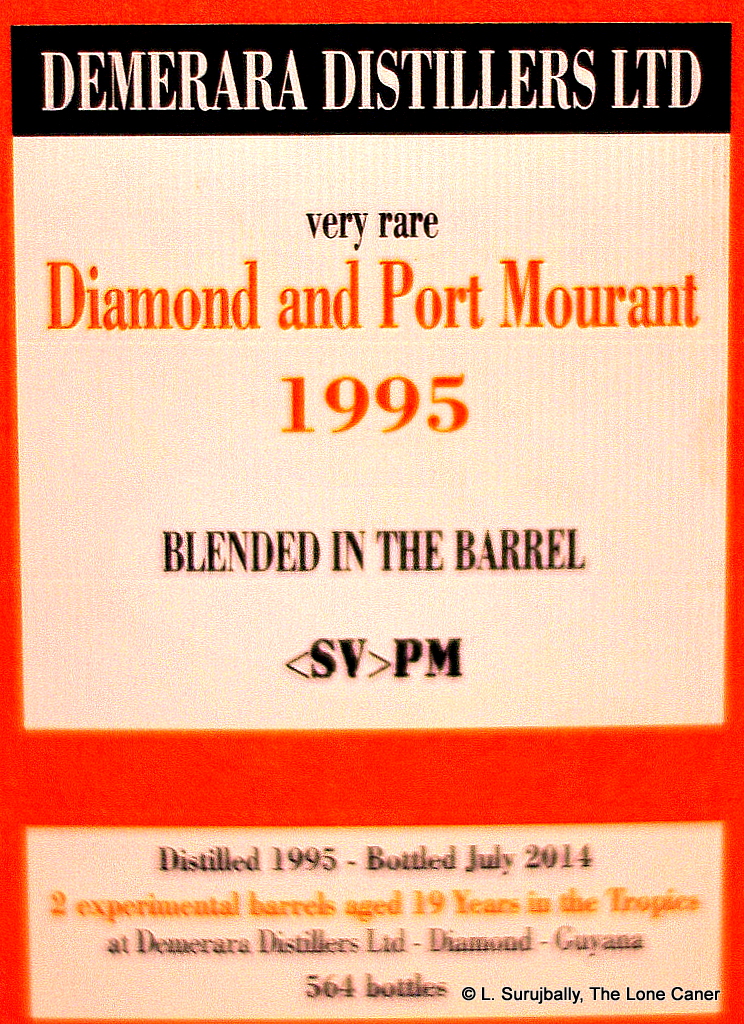

Which may not be too far from the truth. Originally the rum handed out in the 18th and 19th centuries was a Barbados- or Jamaican-based product. But as time went on, various other more complex and blended rums were created and sold to the navy by companies such as Lamb’s, Lemon Hart, C&J Dingwall, George Morton and others. Marks were created from estates like Worthy Park, Monymusk, Long Pond, Blue Castle (all in Jamaica); from Mount Gilboa in Barbados; from Albion and Port Mourant in Guyana; and quite a few others. Gradually this fixed the profile of a navy rum as being one that combined the characteristics of all of these (Jamaica being the tiniest due to its fierce pungency), and being blended to produce a rum which long experience had shown was preferred by the sailors. E.D.&F. Man was the largest supplier of rums to the navy, and it took the lead in blending its own preferred style, which was actually a solera – this produced a blend where the majority of the rum was less than a decade old, but with aspects of rums much older than that contained within it.

The problem was that the depot (and all records about the vats and their constituent rums) was damaged, if not outright destroyed during the 1941 Blitz. In effect this means that what we were looking at here was a rum, blended, and aged solera style, that was in all likelihood re-established in the 1940s only, and that means that the majority of the blend would be from the sixties, with aged components within it that reasonably date back to twenty years earlier. And that might account for the taste profile I sensed.

So now what? We’ve tasted a sorta-kinda 1960s rum, we’ve accepted that this was “the way rums were made” with some serious, jowl-shaking, sage nods of approval. We’ve established it has a fierce, thick, dark taste, as if a double-sized magnum of Sunset Very Strong ravished the Supreme Lord VI and had a gently autistic child. It had a serious nose, excellent taste, and finished reasonably strong, if perhaps without flourish or grandeur. The question is, is it worth the price?

Now Pusser’s bought the recipe years ago and in theory at least, they’re continuing the tradition. Try their Original Admiralty Blend (Blue Label), the Gunpowder Strength or the fifteen year old, and for a lot less money you’re going to get the same rum (more or less) as the Jolly Jack Tars once drank. Why drop that kinda cash on the Tot, when there’s something that’s still being made that supposedly shares the same DNA? Isn’t the Pusser’s just as good, or better? Well, I wouldn’t say it’s better, no (not least because of the reported 29 g/l sugar added). But at over nine hundred dollars cheaper, I have to wonder whether it isn’t a better bargain, rather than drinking a bottle like the Tot, with all its ephemeral transience. (Not that it’s going to stop anyone, of course, least of all those guys who buy not one but three Appleton 50s at once).

So this is where your wallet and your heart and your brain have to come to a compromise, as mine did. See, on the basis of quality of nose and palate and finish – in other words, if we were to evaluate the rum blind without knowing what it was – I’d say the Black Tot last Consignment is a very well blended product with excellent complexity and texture. It has a lot of elements I appreciate in my rums, and if it fails a bit on the back stretch, well, them’s the breaks. I’ll give what I think is a fair score that excludes all factors except how it smells, tastes and makes me feel. Because I have to be honest – it’s a lovely rum, a historical blast from the past, and I don’t regret getting it for a second.

At the end, though, what really made it stand out in my mind, was the pleasure I had in sharing such a piece of rum heritage with my friends. I have cheaper rums that can do the trick just as easily. But they just wouldn’t have quite the same cachet. The same sense of gravitas. The overall quality. And that’s what the money is for, too.

(#237. 87/100)

Other notes:

I’m aware this review is a bit long. I tend to be that way, get really enthusiastic, when a rum is very old, very pricey or very very good. I’ll leave it to you to decide which one applies here.

Rumanicas Review 010 | 0410

Rumanicas Review 010 | 0410

Rumaniacs Review 004 | 0404

Rumaniacs Review 004 | 0404