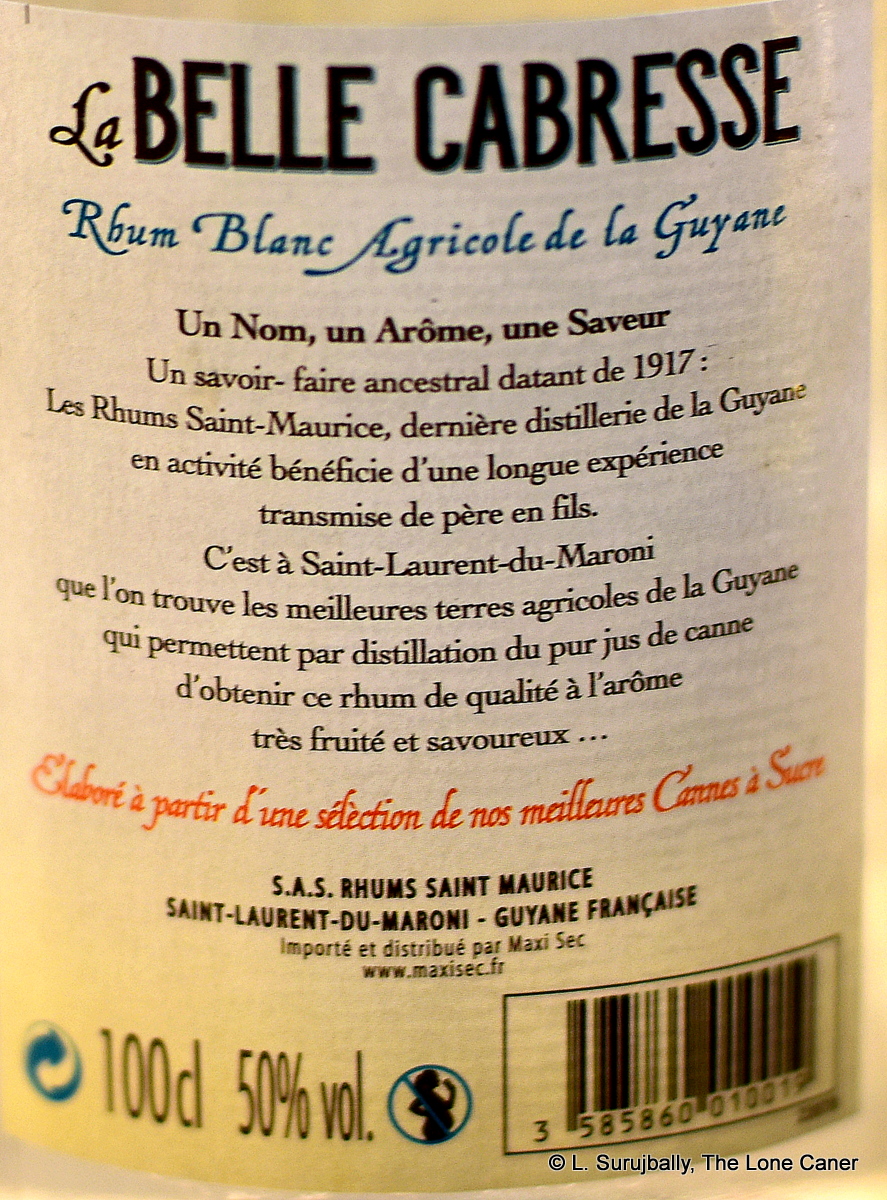

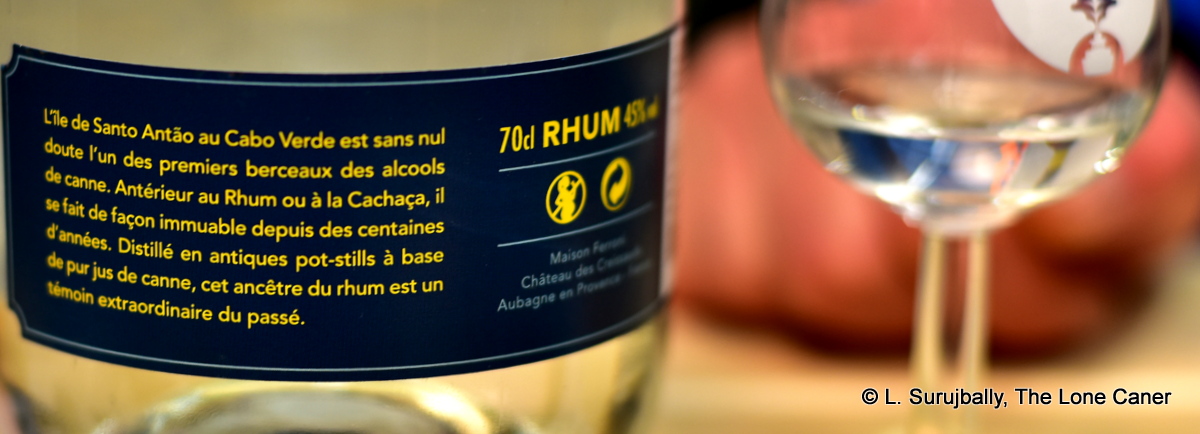

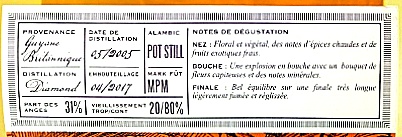

In case you’re wondering, in the parlance of the Francophone West Indies the term “cabresse” (or “chabine”) refers to a light skinned mulatto, what Guyanese would call a dougla gyal – not altogether politically correct these days, but French Caribbean folks have always been somewhat more casual about such terms (witness the “Negrita” series of rums, for example) so perhaps for them it’s less of a big deal. The rum in question comes from French Guiana in this case, made there by the same distillery of St. Maurice which also provides the stock for the rhums of that little indie out of Toulouse, Toucan. It is now the only distillery in the country, though back in the 1930s there were about twenty others.

The blanc is the standard white rum of the company and the brand name of La Cabresse – other brands they make are La Cayennaise and La Coeur de Chauffe, none of which I’ve tried thus far. Like all their rums, its a column still product based on a 48-hour fermentation cycle of the fresh cane juice harvested from their own fields, and it’s bottled at what could almost be seen as a standard for whites, 50% ABV. And that’s sufficient to give it some heft while not being too milquetoast for a hard charging bar cocktail.

Certainly it gives the flavours ample room to emerge. It’s self-evidently a cane juice rhum, redolent of fresh wet grass, sugar cane sap, swank, and white fruits like ripe pears and guavas, and without any tart tang or bite. There’s a touch of avocados, brine and olives mixed up with lime leaves, and a clear hint of anise in the background.

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

When it comes to French island rums, agricoles or otherwise, my attention tends to be attracted more by the whites than the majority of the aged rhums. It’s not that the older rhums are bad by any stretch – quite the reverse, in fact – just that I find the whites fascinating and original and occasionally just plain weird. There’s usually something interesting about them, even when they are perfectly normal products. Perhaps it’s because I was raised on whites that were too often bland, lightly-flavoured and inoffensive and just served their purpose of providing a jolt of alcohol to a mix, that I appreciate rums willing to take a chance here and there.

Not all whites conform to that, of course, and this one isn’t going to break the mould, or the bank, or your tonsils. It’s a perfectly serviceable mid-level white rum, nothing extra special, nothing extra bad. It’s not a crazy screaming face-melter, nor a boring, take-one-sip-and-fall-asleep yawn-through. I’d suggest it’s a little too rough to take neat, while also lacking that element of crazy that makes you want to try it that way just to prove you could; and at the same time it is sprightly enough to boost a cocktail like a Ti’Punch real well. At the end, then, you could with justification state that La Belle Cabresse remains one of those all-round rhums which doesn’t excel at anything in particular, but provides solid support for just about everything you want it for.

(#674)(82/100)

This is a rum that has become a grail for many: it just does not seem to be easily available, the price keeps going up (it’s listed around €300 in some online shops and I’ve seen it auctioned for twice that amount), and of course (drum roll, please) it’s released by Richard Seale. Put this all together and you can see why it is pursued with such slack-jawed drooling relentlessness by all those who worship at the shrine of Foursquare and know all the releases by their date of birth and first names.

This is a rum that has become a grail for many: it just does not seem to be easily available, the price keeps going up (it’s listed around €300 in some online shops and I’ve seen it auctioned for twice that amount), and of course (drum roll, please) it’s released by Richard Seale. Put this all together and you can see why it is pursued with such slack-jawed drooling relentlessness by all those who worship at the shrine of Foursquare and know all the releases by their date of birth and first names.

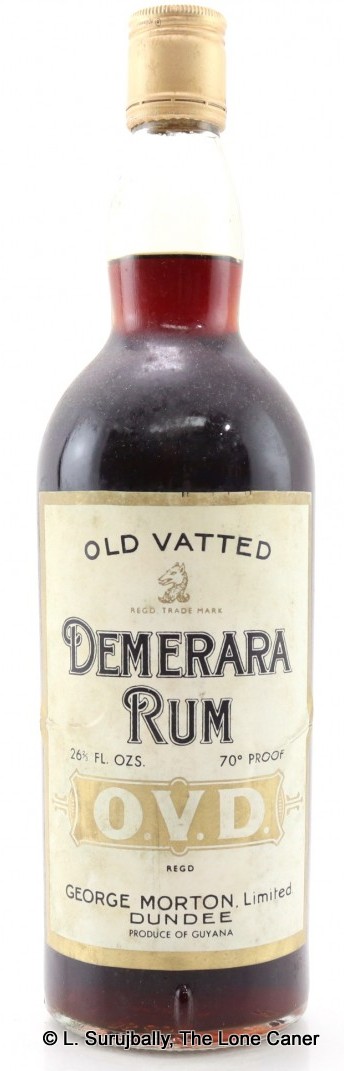

This bottle notes George Morton, founded in 1838, as being located in Dundee which the OVD history page confirms as being the original offices. But a 1970s-dated Aussie listing for a 40% ABV OVD rum already shows them as being located in Glasgow, and a newer bottle label shows Talgarth Rd in London, so my Dundee edition has to be earlier. Lastly, an auction site lists a similar bottle from the 1970s with a label also showing Dundee, and a spelling of “Guyana”, so since the country became independent in 1966, I’m going to suggest the early 1970s is about right

This bottle notes George Morton, founded in 1838, as being located in Dundee which the OVD history page confirms as being the original offices. But a 1970s-dated Aussie listing for a 40% ABV OVD rum already shows them as being located in Glasgow, and a newer bottle label shows Talgarth Rd in London, so my Dundee edition has to be earlier. Lastly, an auction site lists a similar bottle from the 1970s with a label also showing Dundee, and a spelling of “Guyana”, so since the country became independent in 1966, I’m going to suggest the early 1970s is about right

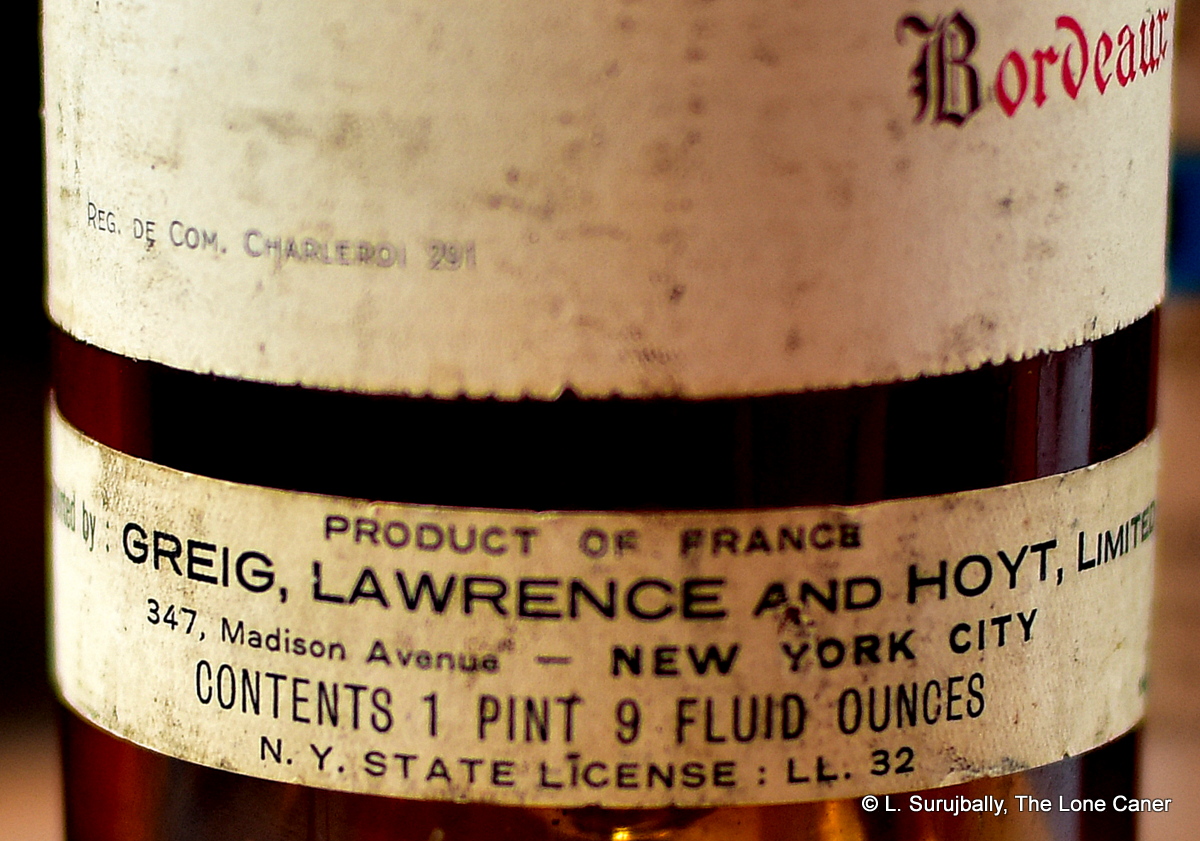

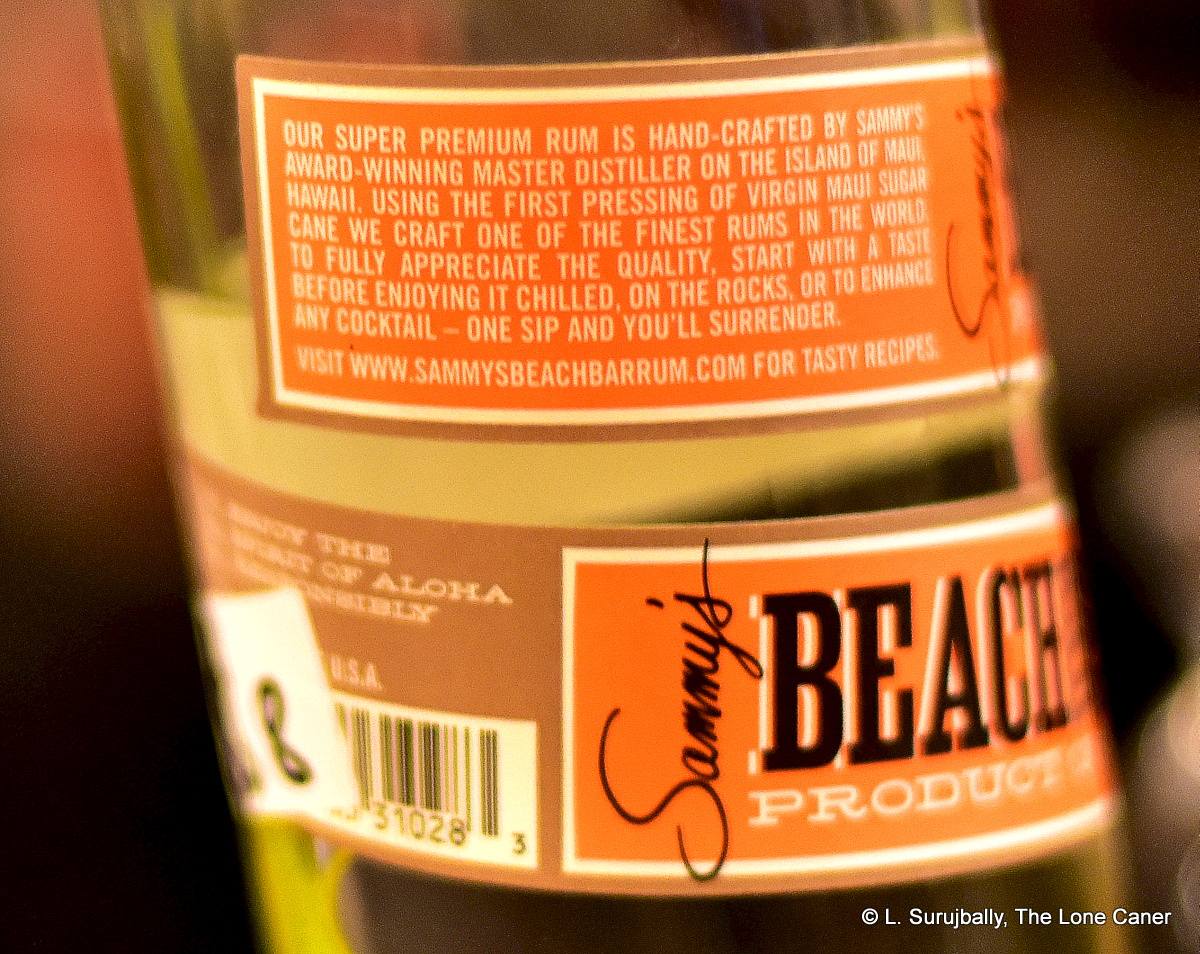

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the  With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

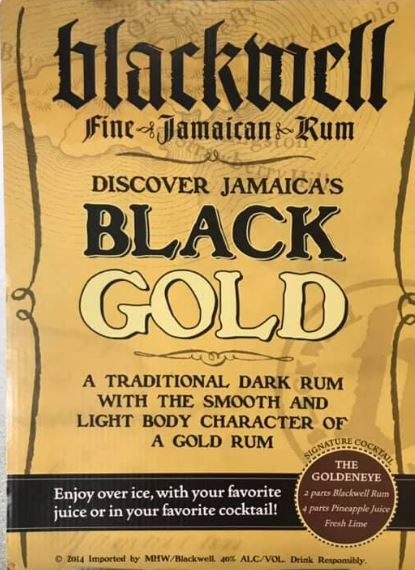

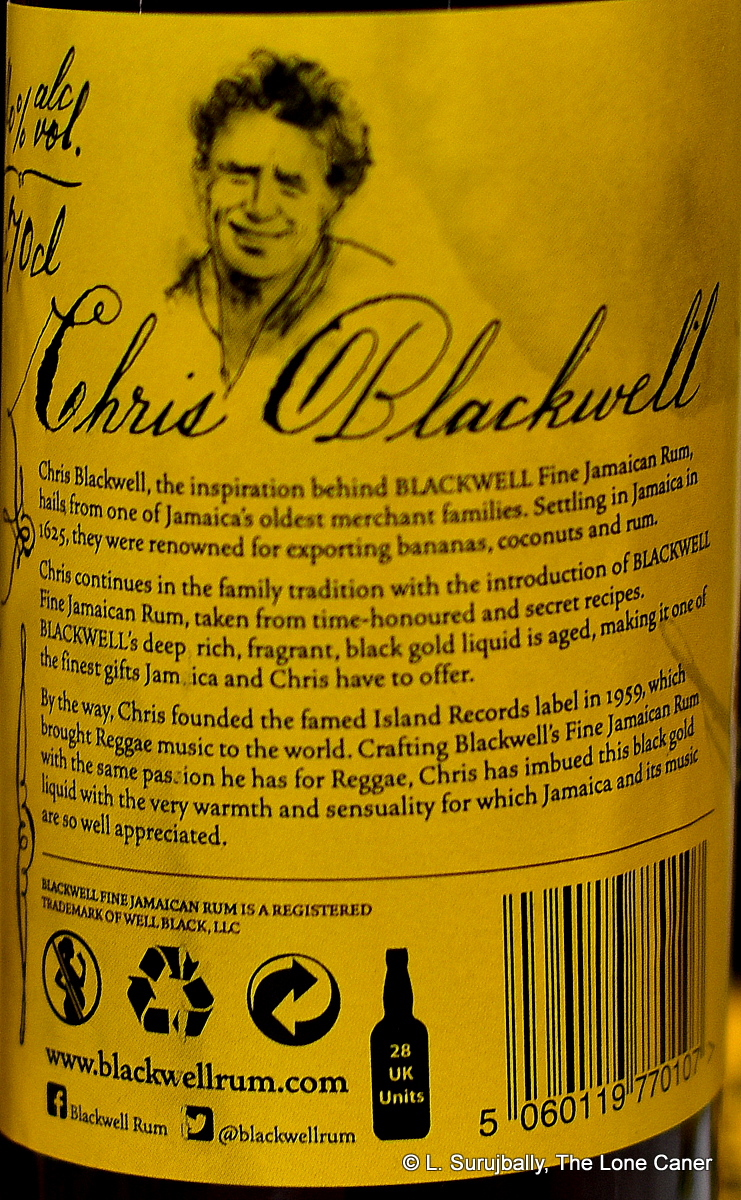

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in  With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

Consider first the nose of this

Consider first the nose of this

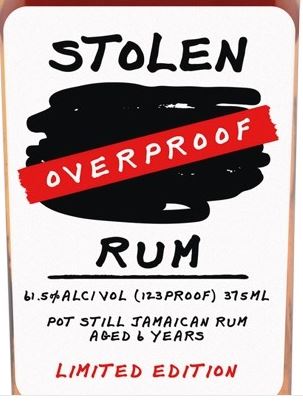

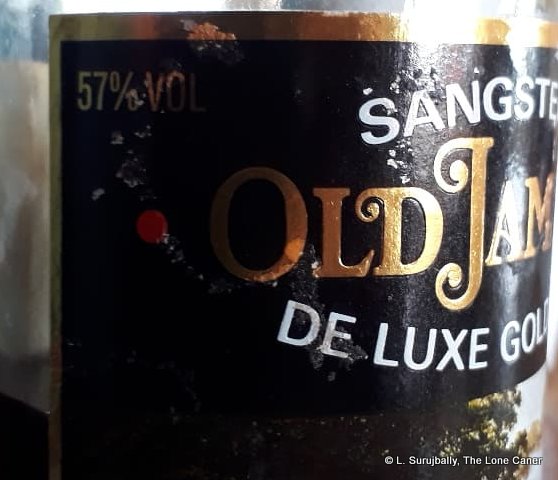

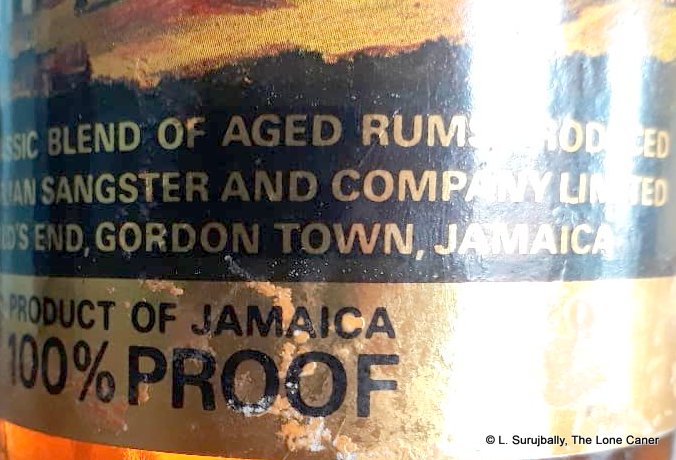

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued.

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued. Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.

Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.  Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones.

Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones. Rumaniacs Review # 096 | 0617

Rumaniacs Review # 096 | 0617

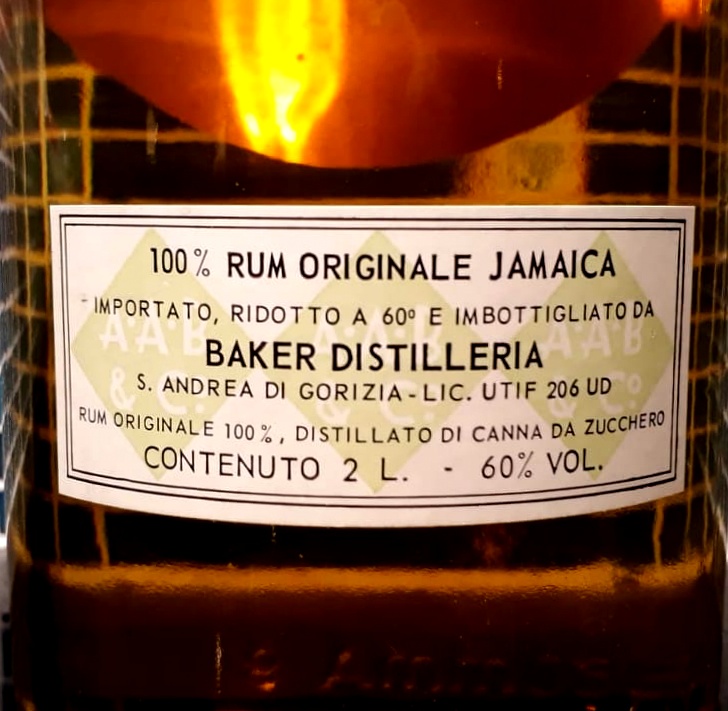

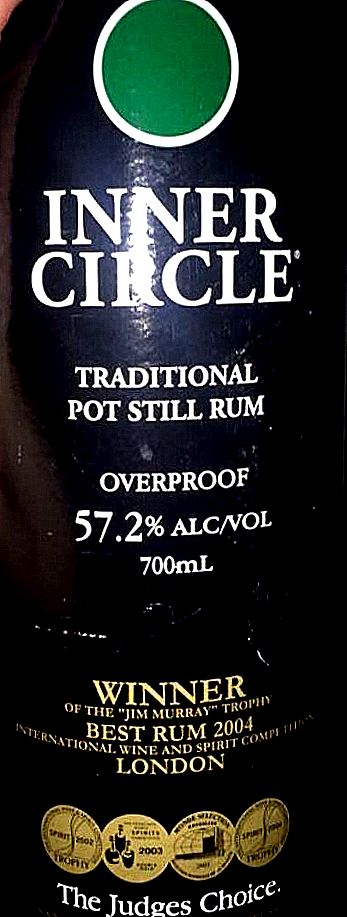

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything.

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything.