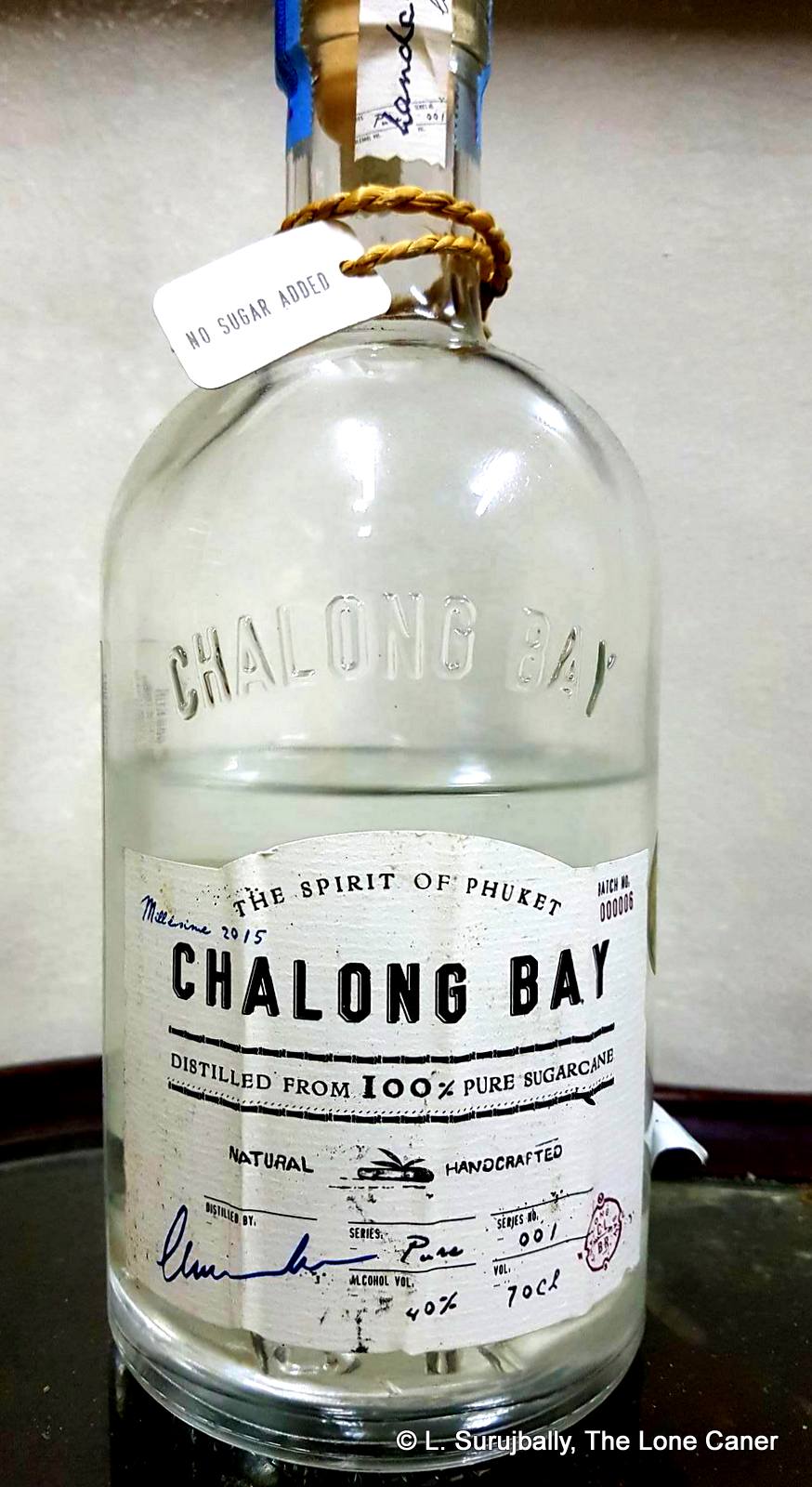

It must be something about the French – they’re opening micro distilleries all over the place (Chalong Bay, Sampan, Whisper, Issan and Toucan are examples) and almost all of them are channelling the agricole ethos of the French West Indies, working with pure cane juice and bringing some seriously interesting unaged blancs to the attention of the world. Any time I get bored with the regular parade of rums from the lands of the pantheon, all I have to do is reach for one of them to get jazzed up about rum, all over again. í

The latest of these little companies is from Vietnam, which is rife with sugar cane juice (“Nuoc Mia”) as well as locally made bottom-house rice- or molasses-originating artisanal spirits called “rượu” (ruou); these operate in the shadows of any Government regulation, registration or oversight — many are simple moonshineries. But Saigon Liquorists is not one of these, being the formally incorporated enterprise of two expatriate Frenchmen Clément Jarlier and Clément Daigre, who saw the cane juice liquor being sold on the streets in Ho Chi Minh City and smelled a business opportunity. The fact that one was involved in spirits distribution in Vietnam while the other had both broker experience and knew about the distillation of cognac didn’t hurt wither – already they had a background in the industry.

Photo (c) Saigon Liquorists, from FB

Sourcing a 200-liter single column still in 2017 from China, they obtained fresh cane, then the juice, experimented for three months with fermentation, distillation, cutting, finally got the profile they were after, and rolled out the first Rhum Mia in October that year at a local charity gala. In their current production system, the sugarcane comes from Tien Giang in the Mekong Delta, just south of Ho Chi Minh City, via a supplier who collects it from farmers in the area and does the initial processing. The sugarcane is peeled, and pressed once to get the first juice. That is then vacuum-packed in 5L bags and loaded into refrigerated trucks (this slows down fermentation), which transport the bags the 70km to the distillery. There fermentation is begun and lasts about five days, before being run through the still – what comes out the other end is around 77% ABV. The rum is rested in inert, locally-made traditional clay vessels called chums (used in rice liquor fermentation in Vietnam) for eight months and then slowly diluted with water over the final two months to 45% – a strength chosen to appeal to the local market where Mia’s initial sales were made.

The strength might prove key to broader acceptance in foreign markets where 50-55% ABV is more common for juice-based unaged rhums (Toucan had a similar issue with the No.4, as you may recall). When I nosed this 45% rhum, its initial smells took me aback – there was a deep grassy kind of aroma, mixed in with a whole lot of glue, book bindings, wax, old papers, varnish and furniture polish, that kind of thing. It reminded me of my high school studies done in GT’s National Library, complete with the mustiness and dry dust of an old chesterfield gone to mothballs, under which are stacked long unopened suitcases from Edwardian times. And after all that, there came the real rum stuff – grass, dill, sweet gherkins, sugar water, white guavas and watermelon, plus a nice clear citrus hint. Quite a combo.

The rhum distanced itself from the luggage, furniture and old tomes when I tasted it. The attack was crisp and clean on the tongue, sharp and spicy, an unambiguous blade of pure herbal and grassy flavours – sweet sugar cane sap, dill, crushed lime leaves, brine, olives, with just a touch of fingernail polish and turpentine at the back end, as fleeting as a roué’s sly wink. After about half an hour – longer than most will ever have this thing gestating in their glasses – faint musty dry earth smells returned, but were mixed in with sugar water, cucumbers and pimentos, cumin, and lemongrass, so that was all good. The finish was weak and somewhat quick, quite aromatic and dry, with nice hints of flowers, lemongrass, and tart fruits.

Ultimately, it’s a reasonably tasty tropical drink that would do fine in (and may even have been expressly designed for) a ti-punch, but as a rhum to have on its own, it needs some torqueing up, since the flavours are there, but too difficult to tease out and come to grips with. Based on the experience I’ve had with other micro-distilleries’ blancs (all of which are stronger), the Mia is damned intriguing though. It’s different and unusual, and in my correspondence with him, Clement suggested that this difference comes from the fact that the sugar cane peel is discarded before pressing which makes for a more grassy taste, and he takes more ‘heads’ away than most, which reduces flavour somewhat…but also the hangover, which, he remarked, is a selling point in Vietnam.

These days I don’t drink enough to get seriously wasted any more (it interferes with my ability to taste more rums), but if this easy-on-the-head agricole-style rhum really does combine both taste and a hangover-free morning after, and if the current fascination with grass-to-glass rums continues in the exclusive bars of the world – well, I’m not sure how you could stop the sales from exploding. Next time I’m in the Real World, I’ll keep an eye out for it myself.

(#680)(76/100)

Other Notes

- All bottles, labels and corks are sourced in Vietnam and efforts are underway to begin exporting to Asia and Europe.

- Production was around 9000 bottles a year back in 2018, so it might have increased since then.

- This batch was from 2018

- Plans are in play to distill both gins and vodkas in the future.

- Hat tip to Reuben Virasami, who spotted me the sample and alerted me to the company. Also to Tom Walton, who explained what “chums” were. And many thanks to Clément Daigre of SL, who patiently ran me through the history of the company, and its production methods.

I’ve never been completely clear as to what effect a resting period in neutral-impact tanks would actually have on a rum – perhaps smoothen it out a bit and take the edge off the rough and sharp straight-off-the-still heart cuts. What is clear is that here, both the time and the reduction gentle the spirit down without completely losing what makes an unaged white worth checking out. Take the nose: it was relatively mild at 40%, but retained a brief memory of its original ferocity, reeking of wet soot, iodine, brine, black olives and cornbread. A few additional nosings spread out over time reveal more delicate notes of thyme, mint, cinnamon mingling nicely with a background of sugar water, sliced cucumbers in salt and vinegar, and watermelon juice. It sure started like it was out to lunch, but developed very nicely over time, and the initial sniff should not make one throw it out just because it seems a bit off.

I’ve never been completely clear as to what effect a resting period in neutral-impact tanks would actually have on a rum – perhaps smoothen it out a bit and take the edge off the rough and sharp straight-off-the-still heart cuts. What is clear is that here, both the time and the reduction gentle the spirit down without completely losing what makes an unaged white worth checking out. Take the nose: it was relatively mild at 40%, but retained a brief memory of its original ferocity, reeking of wet soot, iodine, brine, black olives and cornbread. A few additional nosings spread out over time reveal more delicate notes of thyme, mint, cinnamon mingling nicely with a background of sugar water, sliced cucumbers in salt and vinegar, and watermelon juice. It sure started like it was out to lunch, but developed very nicely over time, and the initial sniff should not make one throw it out just because it seems a bit off.

Consider first the nose of this

Consider first the nose of this

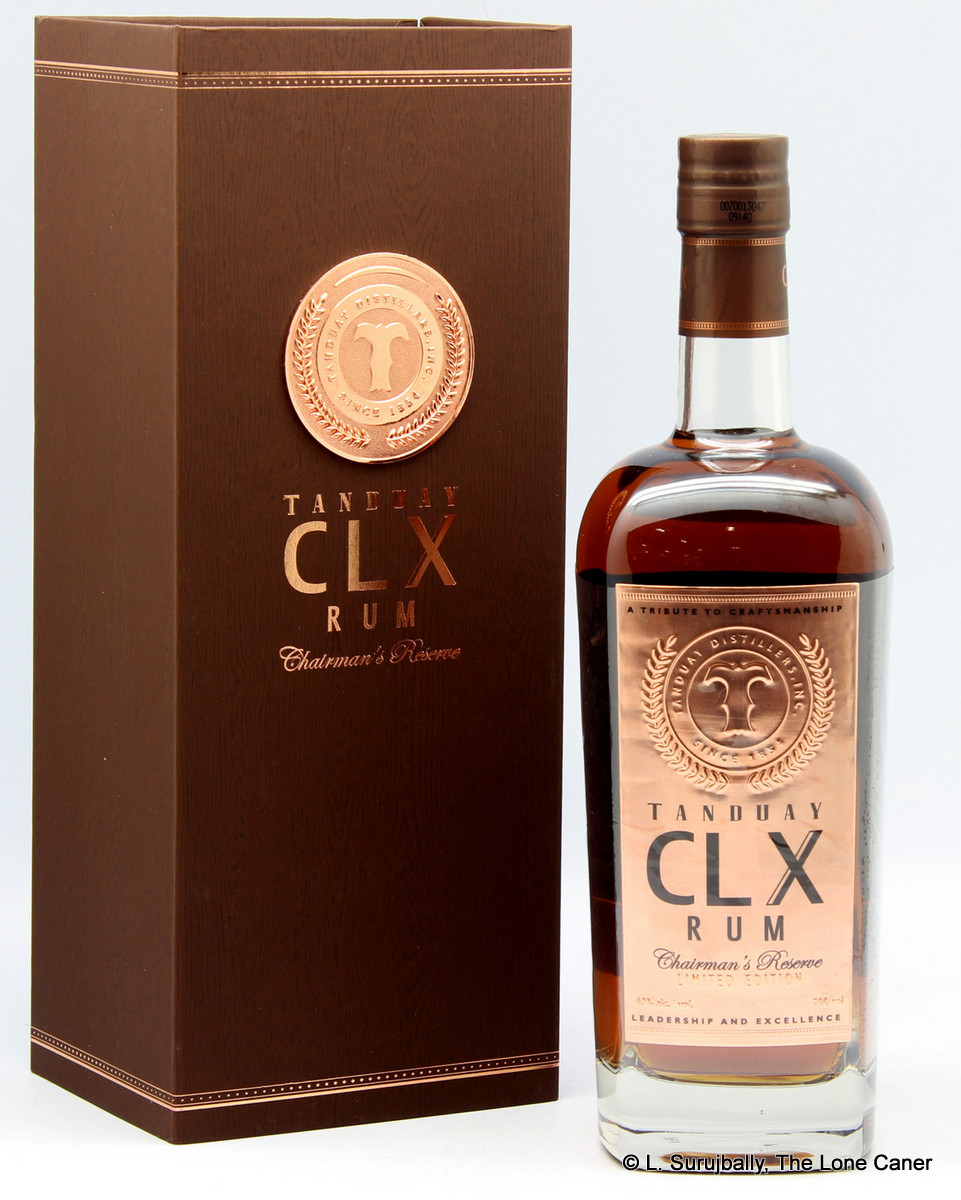

Anyway, when we’re done with do all the contorted company panegyrics and get down to the actual business of trying it, do all the frothy statements of how special it is translate into a really groundbreaking rum?

Anyway, when we’re done with do all the contorted company panegyrics and get down to the actual business of trying it, do all the frothy statements of how special it is translate into a really groundbreaking rum?

Like most rums of this kind, the opinions and comments are all over the map. Some are savagely disparaging, other more tolerant and some are almost nostalgic, conflating the rum with all the positive experiences they had in Thailand, where the rum is made. Few have had it in the west, and those that did weren’t writing much outside travel blogs and review aggregating sites.

Like most rums of this kind, the opinions and comments are all over the map. Some are savagely disparaging, other more tolerant and some are almost nostalgic, conflating the rum with all the positive experiences they had in Thailand, where the rum is made. Few have had it in the west, and those that did weren’t writing much outside travel blogs and review aggregating sites.

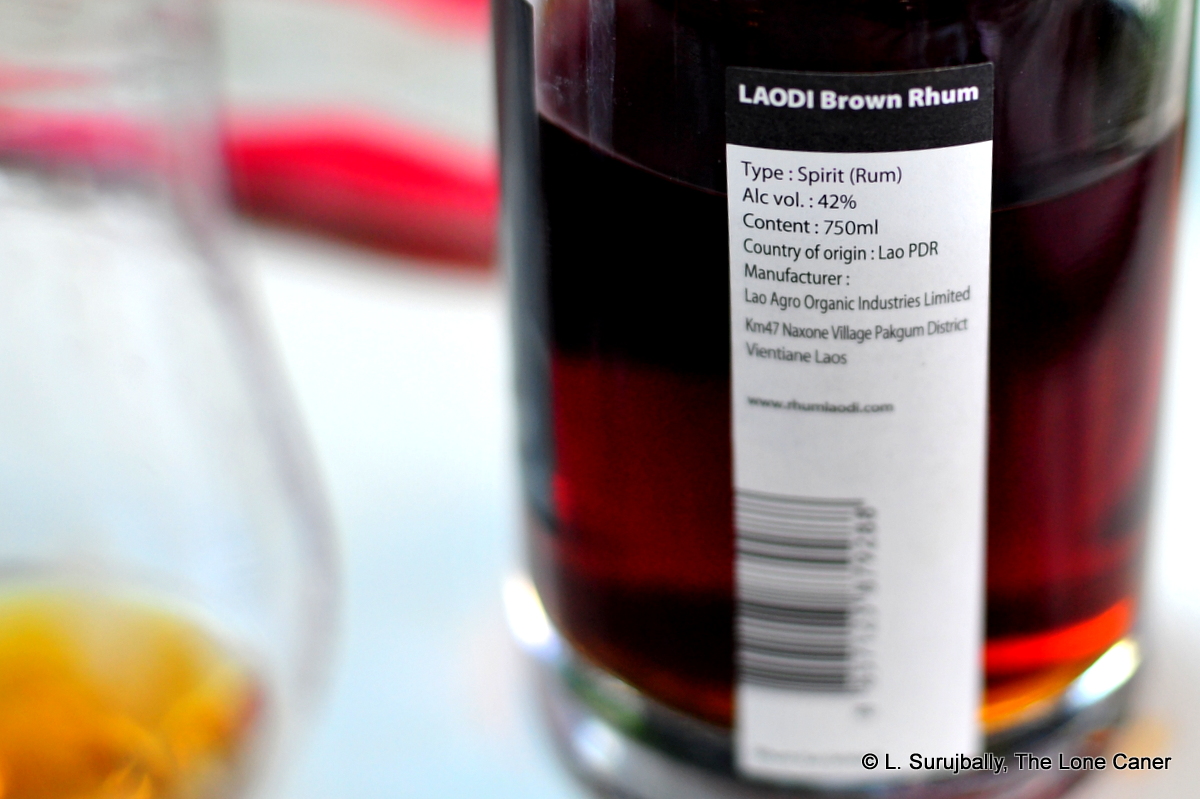

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything.

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything. Now here’s an interesting standard-proofed gold rum I knew too little about from a country known mostly for the spectacular temples of Angor Wat and the 1970s genocide. But how many of us are aware that Cambodia was once a part of the Khmer Empire, one of the largest in South East Asia, covering much of the modern-day territories of Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Viet Nam, or that it was once a protectorate of France, or that it is known in the east as Kampuchea?

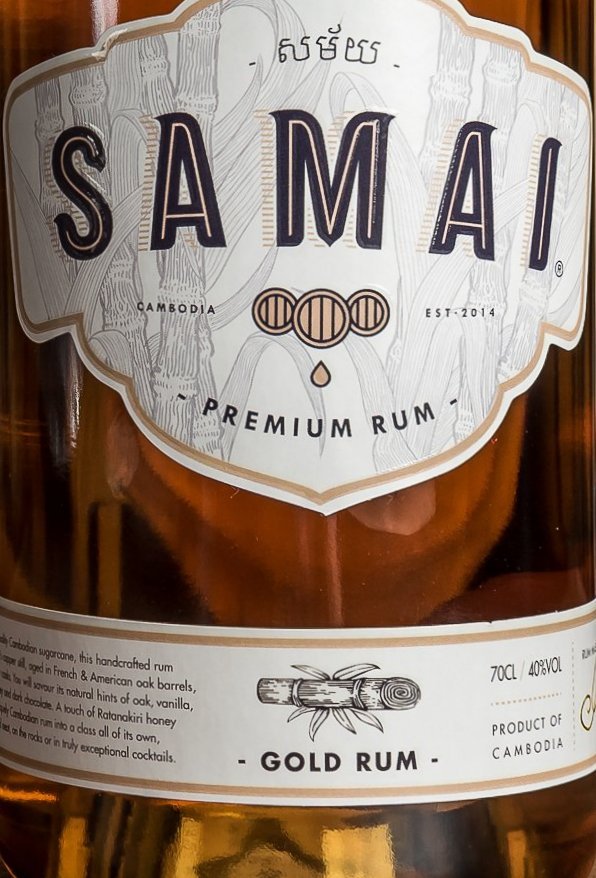

Now here’s an interesting standard-proofed gold rum I knew too little about from a country known mostly for the spectacular temples of Angor Wat and the 1970s genocide. But how many of us are aware that Cambodia was once a part of the Khmer Empire, one of the largest in South East Asia, covering much of the modern-day territories of Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Viet Nam, or that it was once a protectorate of France, or that it is known in the east as Kampuchea? Thailand doesn’t loom very large in the eyes of the mostly west-facing rum writers’ brigade, but just because they make it for the Asian palate and not the Euro-American cask-loving rum chums, doesn’t mean what they make can be ignored; similar in some respects to the light rums from Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Panama and Latin America, they may not be rums

Thailand doesn’t loom very large in the eyes of the mostly west-facing rum writers’ brigade, but just because they make it for the Asian palate and not the Euro-American cask-loving rum chums, doesn’t mean what they make can be ignored; similar in some respects to the light rums from Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Panama and Latin America, they may not be rums

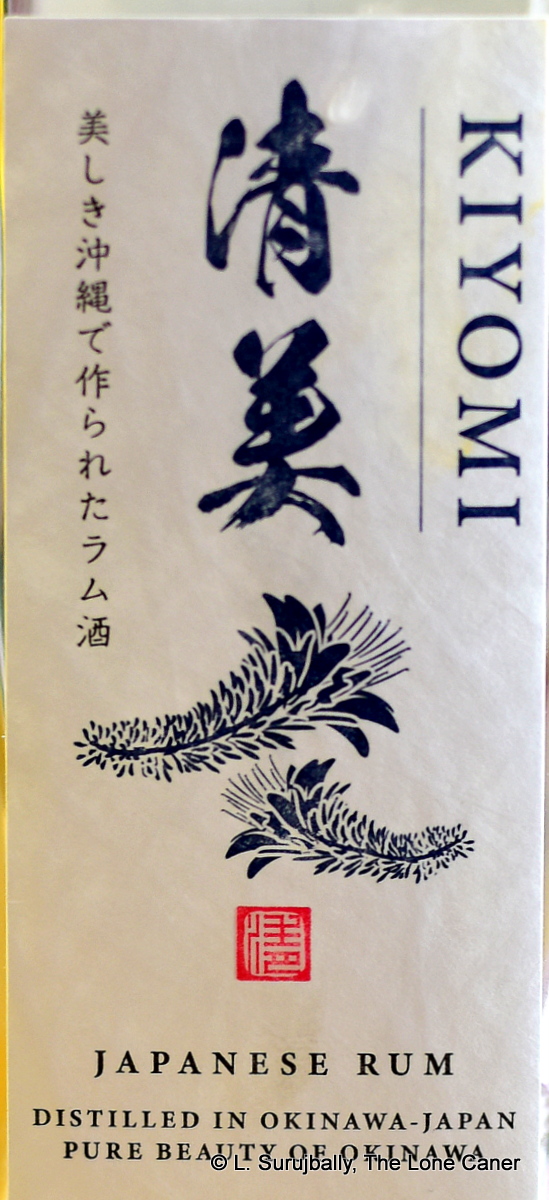

The nose rather interestingly presented hints of a funky kind of fruitiness at the beginning (like a low rent Jamaican, perhaps), while the characteristic clarity and crisp individualism of the aromas such as the other Nine Leaves rums possessed, remained. It was musky and sweet, had some zesty citrus notes, fresh apples, pears and overall had a pleasing clarity about it. Plus there were baking spices as well – nutmeg and cumin and those rounded out the profile quite well.

The nose rather interestingly presented hints of a funky kind of fruitiness at the beginning (like a low rent Jamaican, perhaps), while the characteristic clarity and crisp individualism of the aromas such as the other Nine Leaves rums possessed, remained. It was musky and sweet, had some zesty citrus notes, fresh apples, pears and overall had a pleasing clarity about it. Plus there were baking spices as well – nutmeg and cumin and those rounded out the profile quite well.