Publicity Photo Courtesy of 1423

Introduction: Collections, Series and Special editions

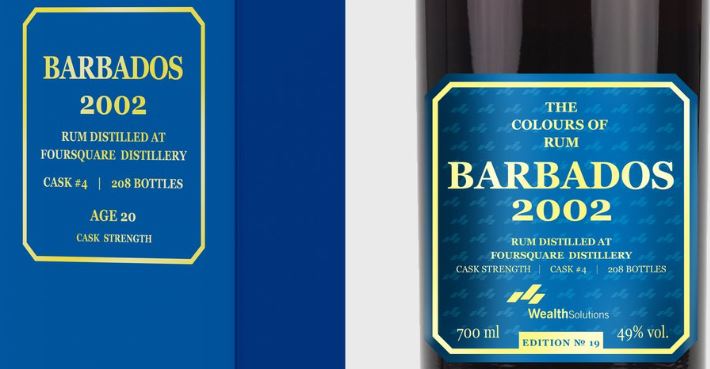

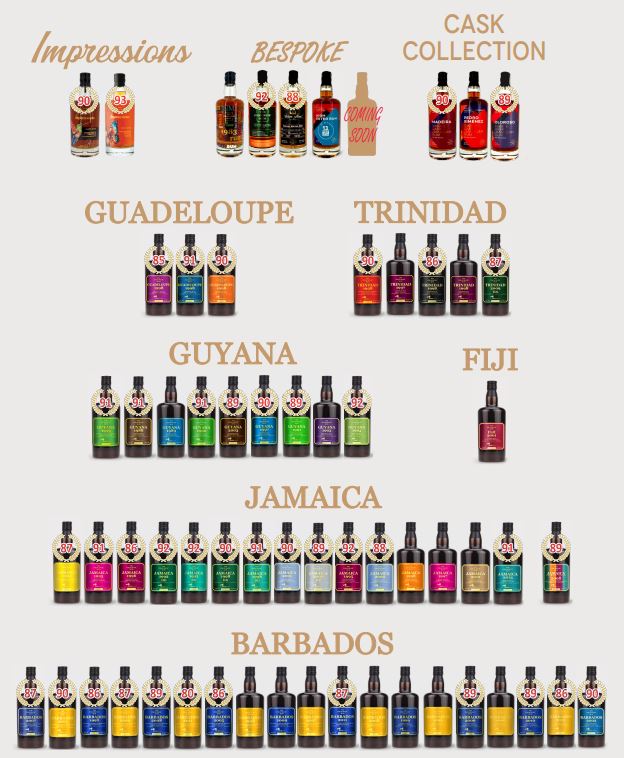

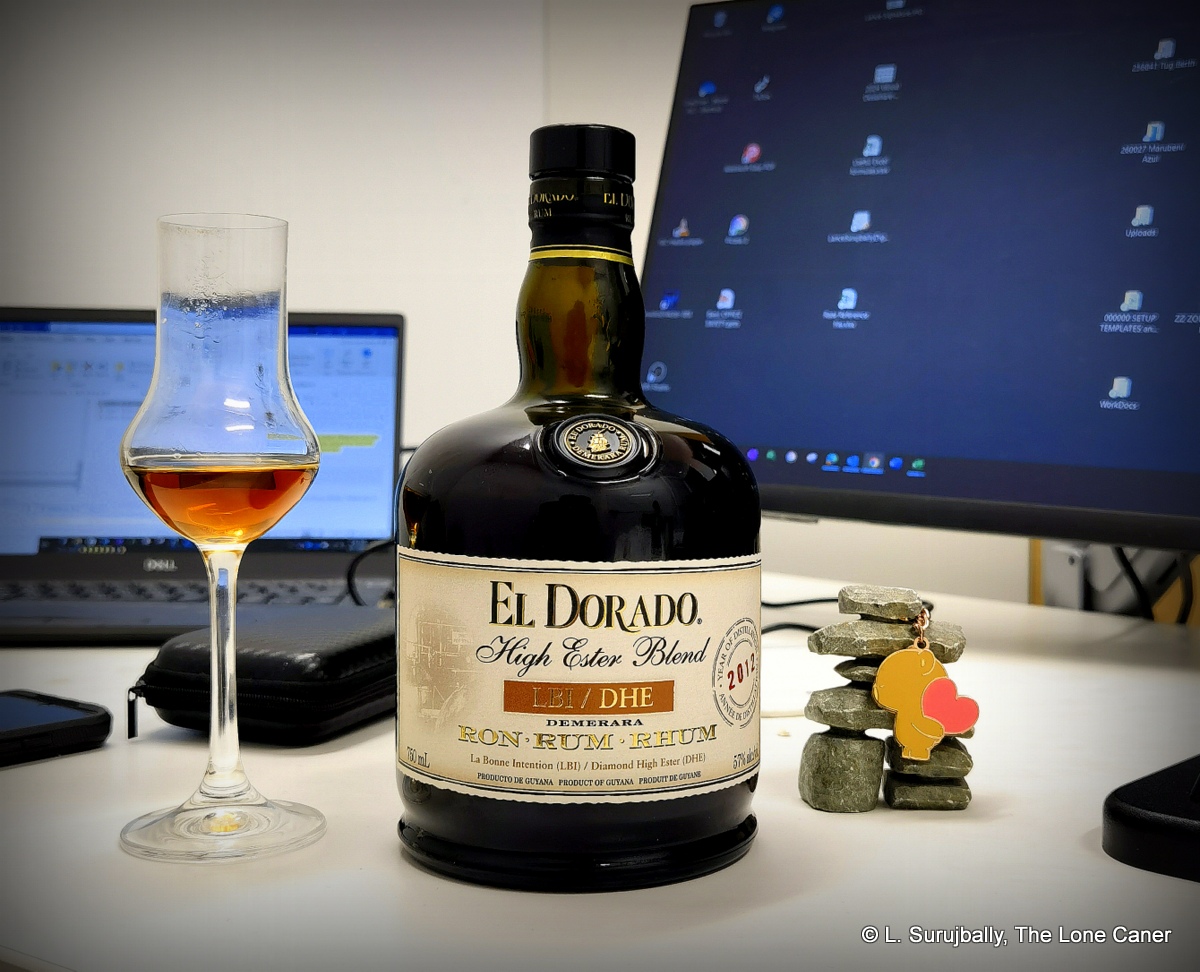

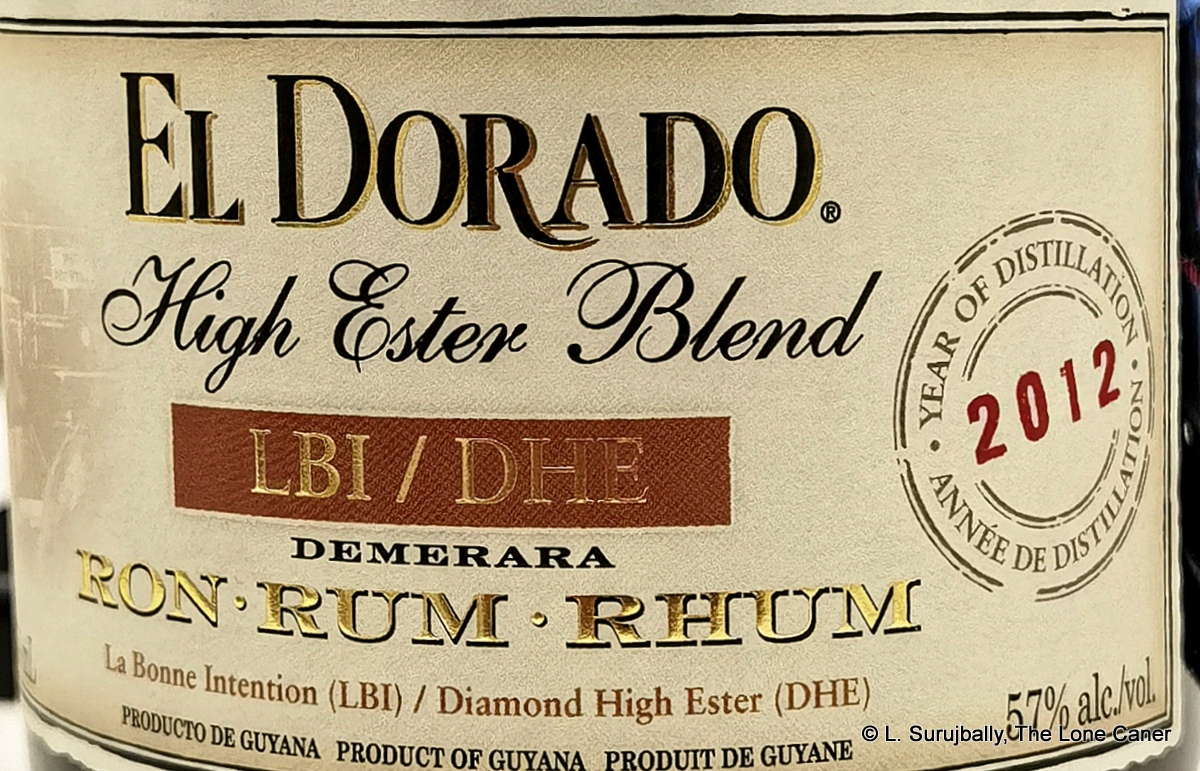

Many independent bottlers sooner or later differentiate their top end rums with a special series of one sort or another. The inspiration might be Cadenhead’s “Green Label” or “Dated Distillation” rums, which are among the earliest extant (at least, as far as I know), but many other major and minor houses have run with the concept over the last two decades – and this is why we see Velier’s varied annual releases (Flags, Demeraras, Caronis, Indian Ocean, Habitation, etc), Rom Delux’s “Wild Series”, Plantation’s “Extreme” collection, Tamosi’s rums, the entire Colours of Rum oeuvre, and many others. It’s questionable whether estate bottlings like the ECS from Foursquare, the various Hampdens, or the cask strength still-specific El Dorados fit the profile as I’ve described it here, but certainly the DNA is at last in part the same: to produce something of real quality that excites the upscale market, and is seen as special, limited, high quality, or all of the above.

Such collections have a peculiarly paradoxical nature. On the one hand they showcase the creme de la creme of the releasing company’s selections: they have limited outturns, are usually single cask, full proof, carefully chosen, and are often very very good. One the other hand, they are sometimes quite pricey, and if priced to move then they can be loss leaders for smaller companies (at best they break even and don’t become a drain on profits), serving more to boost brand image than make cash flow. It’s not often appreciated, but the real money is made with more mass market offerings by the same company whose street cred is boosted by the special release (as many indies, including 1423, have told me).

Most often the releases of this kind are aged, sometimes extremely so – 30+ years of ageing is not unheard of. With some exceptions (the Appleton Hearts Collection comes to mind), they tend to emanate from European brokers (did someone say ‘Scheer’?) and because of their age and rarity, often exceed our financial reach. Few independents take a different route, though Velier with its pot still HV line has bucked the trend better than most, while others just shrug, set their margins, and pray to make payroll. And then, there’s 1423, with this extraordinary series called “Origins”.

The Series

The Series

In all my years reviewing and tasting rums, attending rum festivals and seeing what’s being put out there for us, I have found few releases quite as interesting as the Origins. Quite simply, these are unaged white rums at cask strength, which often relate to other aged rums in the SBS portfolio that have been issued…or will be. They come from varied countries, varied stills, varied sources (juice, molasses, etc) and only share a consistent proof point (57%) and their unaged nature.

To my knowledge, the only other series to which I can reasonably compare them is the HV pot still line, which focuses on the still and can be both aged or unaged, or L’Espirit’s “Still Strength” unaged whites, which are too few and too occasional to be deemed a collection. But here, 1423, the Danish company that makes the Companero, SBS and Esclavo lines of rums, concentrates completely on the distillate itself, and only rests them in inert tanks until they’re ready to be bottled.

As an educational tool for rum lovers, then, this small collection currently has few equals for what it does, which is to showcase rums with no barrel influence and no messing around, allowing purists to sample an original distillate irrespective of where it comes from, what the source is, what kind of still, or what kind of fermentation.

Origins of the “Origins”

1423 was founded in Denmark in 2008, and as it started to find its feet and its markets grew, it found itself in familiar waters already sailed by the likes of Mr Barrett over at Bristol Spirits, or the SMWS: as sales increased and the reputation of the company expanded, it was not always possible to get just a barrel here or a barrel there. At some point it began to make sense to import new-make (i.e. unaged) spirit from their clients, and age it themselves.

My initial supposition was that since they had spare raw rum stock from time to time, this was one way to get rid of any excess, while simultaneously educating the consumers who might have wanted to delve deeper into the wild world of white spirits.

But, Josh Singh, one of the owners denied this. “The idea for […] Origins was developed by our sales and marketing team in cooperation. We had a situation where we were increasing our purchases of unaged rum from distilleries across the world. […] The unaged rum in most cases was only tasted internally and everyone was impressed with the quality, so the idea […] was to find a way to showcase this quality to others outside of 1423 and share what eventually would become our classic S.B.S. in the future.

Reception and Other Matters

Reception and Other Matters

These are rums for the true rum lover who is interested in seeing what a distillate is like before the barrel does its magic. In that sense, 1423 is acting much as Luca Gargano did, as an educator for those who want to go deeper into the whole business of how rums are when they come frothing and boiling off the still, but before they have been tamed or blended into other rums. And unlike what Velier has done, these are not really limited editions – many of them have annual releases of new stock so there is some batch variation from time to time but (with some exceptions) no shortage of quantity.

On the other hand, one wonders whether the black bottles are meant to hide the fact that they are white rums (often seen as cocktail fodder only) or a subtle tongue in cheek nod to Velier, who popularised the look. Factoring in the bright and attention-grabbing labels which were developed in-house, it’s probably a bit of both.

All that said, the Single Origin Rum series remain something of an under-the-radar set of bottlings. Few social media posts about them exist, reviews are scanty (see other notes, below, for two of them) and their importance, and quality, tends to be overlooked. I argue that this is an oversight and they should garner much more attention – and plaudits – than they have so far gotten.

But even so, and even with only eleven separate releases as of 2024, the collection is remarkable for its diversity, which is something I see no reason to doubt will grow in the years to come (the first edition came out in 2022). There are cane juice rums from Jamaica, from Ecuador, from the Dominican Republic; high ester rums from those same countries plus the French Antilles; there are molasses based rums from yet other countries, an Australian rum specifically not from Bundaberg or Beenleigh; column still rums, pot still rums, and all of them are bottled at 57% for easy comparison. That’s a hell of a listing, made at right angles to what we usually get from their producers.

If the series has weaknesses – and which does not? – they are relatively minor. For my money I would have preferred them at still or original strength, not taken down to a similar proof across the board (though I concede it does aid in comparability if one is touring the entire line at once). That said, L’Esprit proved the concept of still strength rums years ago, so we don’t need to be babied with 57% all the while, which creates a sort of artificial equivalence we don’t need (if we’re old enough to appreciate these crazy rums to begin with, and as they are, strength should not be spoon fed to us). And of course, there are still too few: eleven bottlings is hardly enough for what we would like to see in a collection like this. I’d like to see more representatives from Haiti, Barbados, Grenada, the USA, India, the Far East, Australasia….the list can be much longer.

If the series has weaknesses – and which does not? – they are relatively minor. For my money I would have preferred them at still or original strength, not taken down to a similar proof across the board (though I concede it does aid in comparability if one is touring the entire line at once). That said, L’Esprit proved the concept of still strength rums years ago, so we don’t need to be babied with 57% all the while, which creates a sort of artificial equivalence we don’t need (if we’re old enough to appreciate these crazy rums to begin with, and as they are, strength should not be spoon fed to us). And of course, there are still too few: eleven bottlings is hardly enough for what we would like to see in a collection like this. I’d like to see more representatives from Haiti, Barbados, Grenada, the USA, India, the Far East, Australasia….the list can be much longer.

Can rums like this make money? Sometimes, but not always. As Josh remarked to me when we were discussing the matter at the German Rum Festival in 2024 (where he was cheerfully pouring me a Brobdingnagian shot of the pot still DR “Consuelo”), the Origins seem to be too niche and too misunderstood, and as such, while they are moving, they are not selling like hot cakes either. This is an issue for many such rum series – they are too different and deemed too odd, departing too much from the mainstream, to attract serious raves. The Renegade pre-cask rums suffered from similar issues of recognition, and even the Habitation Velier line sometimes relies much more on the trust we place in Luca’s selection than their actual worth. My considered opinion is that more attention needs to be paid to such outliers, and generous sharing be done by those who know their rums, so that those with scrawnier purses and less knowledge can be brought on board to see how good they really are.

Clearing the dishes…

Summing up, then, whatever niggling (and mostly personal) observations I may have, the rums are really damned fine and are important products which sooner or later everyone should at least try one of, if only to see how ageing changes a core distillate and how absolutely fascinating a rum can be even when still in diapers. Although there are not too many of them so far, I argue that as a tool enabling us to explore the richness and diversity of rums, this small collection is “Key” in every way that matters. They should not be left to gather dust on shelves, but bought, shared and extolled.

Because, in an ever more homogenised world where it seems like every month we see another new standard rum from another already-well-known distillery, issued at yet another similar strength, we are lucky that we still have companies courageous enough to bring unusual and intriguing and fascinating rums like these to our attention. They enrich us all with their quality.

The Rums Of The Line

Over the last year or two, I have tasted pretty much all of them, but for various reasons the formal published reviews are lagging. I’ll link this list to each review as I write it.

Bottlings from 2022

- Jamaica, WPH, molasses, pot still, 57% ABV, Distilled 2021 Bottled 2022

- Jamaica, “TECA” Long Pond, molasses, pot still, 57% ABV, Distilled 2021 Bottled 2022

- Ecuador “Malacatos”, cane juice, column still, 57% ABV, Distilled 2022 Bottled 2022

- Dominican Republic “Aroma Grande” high ester, cane juice, column still, 57% ABV, Distilled 2021 Bottled 2022

- French Antilles “Grand Arome”, high ester, cane juice, column still, 57% ABV, Distilled 2021 Bottled 2022

- Guyana “Port Mourant”, molasses, pot still, 57%, Distilled 2021 Bottled 2022

Bottlings from 2023

- Australia <KLK> (Killik), Molasses, pot still, 57%, Distilled 2023, Bottled 2023

- Guadeloupe “Red Cane”, Cane Juice, column still, 57% ABV, Distilled 2022 Bottled 2023

- Jamaica, Cane juice, pot still, 57% ABV, Distilled 2022 Bottled 2023

- Jamaica, “TECC” Long Pond, molasses, high-ester, pot still, 57% ABV, Distilled 2022 Bottled 2023

Bottlings from 2024

- Dominican Republic “Consuelo” Cane Juice, pot still, 57% ABV, Distilled 2024 Bottled 2024 (2-4 months resting).

Other notes

- A 12-minute video synopsis has been posted on YouTube

- My thanks to Josh Singh for his assistance in fleshing out my research

- Also a big tip of the trilby to Logan from the Calgary Rum Club, who is always generous with his samples and bottles, especially these. His rum (and whisky) reviews on reddit, where he posts as user “FarDefinition2”, and on IG where he his handle is Logans_Libations, are always worth a read.

For those who want others’ opinions and tasting notes: in February 2023, The Rum Barrel did a comparative of the line, and Rum Revelations also did a range eval in early 2024.

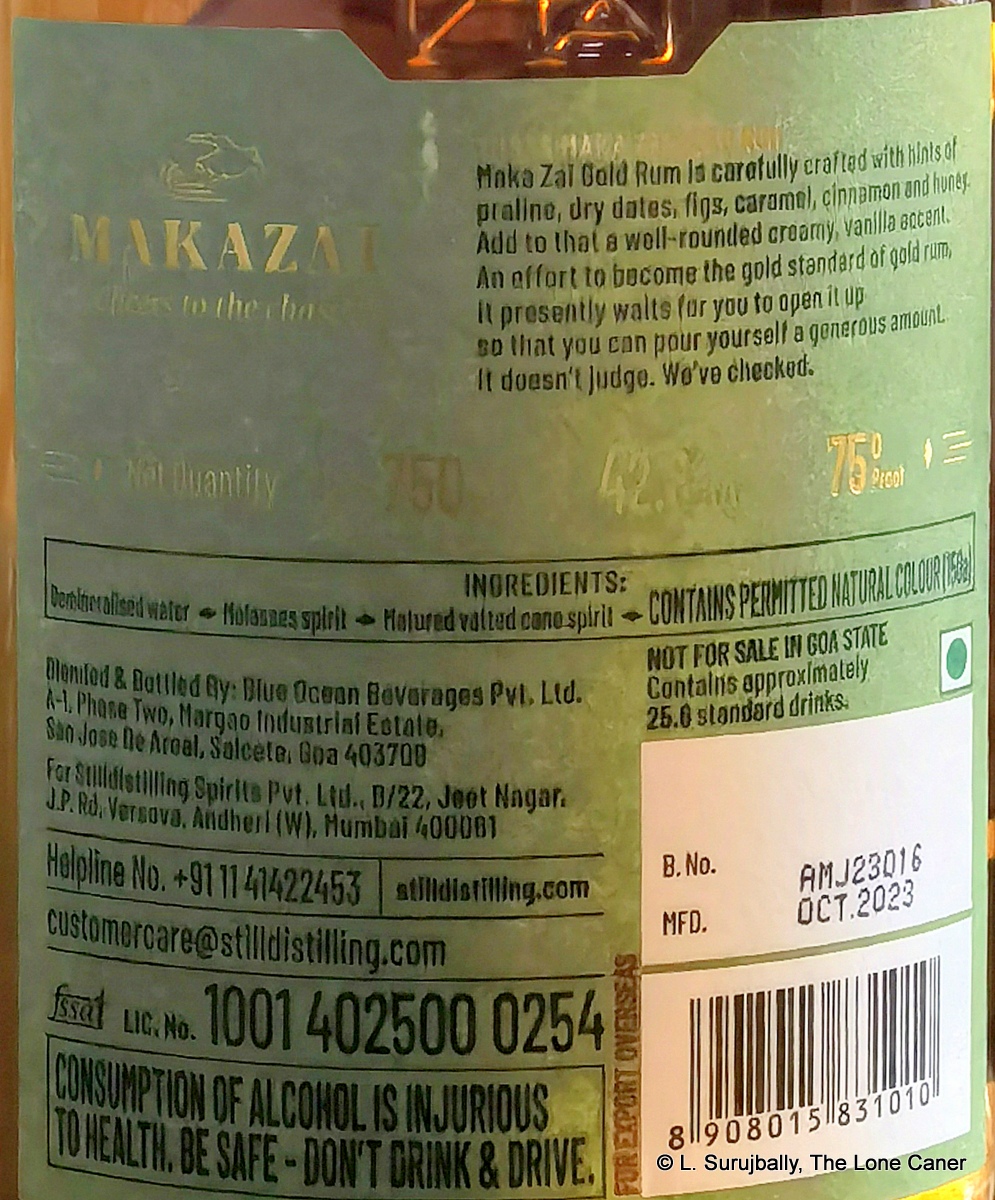

Much of what we sense on the nose is also present when tasted – little of it disappears. There’s the ice cream again, toffee, caramel, salt, vanilla, all present and accounted for. Fruits take on more prominence here, mostly fleshy fruit like soft ripe mangoes and peaches, but we also get black cherries, cranberries, some kiwi fruits and a strong sense of a cinnamon dusted pumpkin latte (go figure). The hint of soup I note above is pretty much gone by the end, unfortunately, but it’s not missed – what we have is more than good enough. The finish sums things up with wine, cherries, light fruits and spices, and lasts a nice long time – it’s a fitting close to the experience, quite pleasant, without introducing any additional notes for our consideration.

Much of what we sense on the nose is also present when tasted – little of it disappears. There’s the ice cream again, toffee, caramel, salt, vanilla, all present and accounted for. Fruits take on more prominence here, mostly fleshy fruit like soft ripe mangoes and peaches, but we also get black cherries, cranberries, some kiwi fruits and a strong sense of a cinnamon dusted pumpkin latte (go figure). The hint of soup I note above is pretty much gone by the end, unfortunately, but it’s not missed – what we have is more than good enough. The finish sums things up with wine, cherries, light fruits and spices, and lasts a nice long time – it’s a fitting close to the experience, quite pleasant, without introducing any additional notes for our consideration.